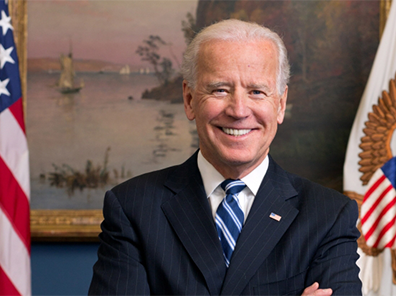

In a recent post, I analyzed shifts in focus of the Biden administration’s migration policies, from targeting “root causes” for migration from the “Northern Triangle” countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to offering extra-legal bribes in the form of “parole” to nationals of Venezuela, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Cuba. The problem with these strategies is that they focus exclusively on “push factors” that encourage migrants to leave home, while ignoring the more significant “pull factors” drawing them to the United States — the most significant being the administration’s refusal to impose consequences (like detention and prosecution) on illegal entrants and enticements in the form of lavish housing and welfare benefits in “sanctuary” jurisdictions for them here. The futility of this push factor strategy is best exemplified by the breathtaking sweep of nationals who are now arriving at our Southwest border.

The Admissions Process and the Grounds of Inadmissibility. The primary focus of every administration’s border strategy — prior to the current one — was on deterring migrants from entering the United States illegally.

In this, those administrations were taking their lead from Congress — the branch that, in our constitutional order, determines which foreign nationals are allowed to enter the country, and which are barred from entry and/or are required to leave. As the Supreme Court has explained:

Policies pertaining to the entry of aliens and their right to remain here are peculiarly concerned with the political conduct of government. In the enforcement of these policies, the Executive Branch of the Government must respect the procedural safeguards of due process. But that the formulation of these policies is entrusted exclusively to Congress has become about as firmly imbedded in the legislative and judicial tissues of our body politic as any aspect of our government. [Emphasis added.]

In accordance with those principles, Congress has established a laundry list of grounds on which foreign nationals are barred from entering the United States, set forth in section 212(a) of the INA and known collectively as the “grounds of inadmissibility”.

The admission process starts before the foreign national ever leaves home. That’s when those who have chosen to come to the United States gather the appropriate documents that will allow them to be admitted at a U.S. port of entry.

For many, that means obtaining an immigrant or nonimmigrant visa at a U.S. consulate abroad. Those nonimmigrants coming from “visa waiver” countries as tourists can skip the trip to the consulate, but they still must complete some paperwork and secure a valid passport.

Visa or passport in hand, foreign nationals then travel to the United States, most arriving to U.S. ports of entry. At that point, CBP follows rules Congress laid out in section 235 of the INA for inspecting foreign nationals (now “aliens” here) and those aliens’ documents, admitting most on a largely pro forma basis.

Given that, the most basic — and logical — of the grounds of inadmissibility are sections 212(a)(6)(A), 212(a)(6)(c), and 212(a)(7)(A). The first bars aliens who have bypassed inspection at the port and crossed the border illegally, the second bars those who presented fraudulent admission documents at the ports, and the third bars aliens who have no valid admission documents at all.

The Detention Mandate for Inadmissible Aliens. Thus, barring the admission of an alien who has entered illegally is the first consequence of illegal entry, but one that means little to an alien who never attempted lawful entry to begin with. Therefore, Congress has provided a second consequence for illegal entrants to prevent them from living and working here without being admitted — detention.

In section 235(b) of the INA, Congress has mandated that aliens who are inadmissible under any of the grounds in section 212(a) of the INA be detained — from the moment of encounter until they are removed from the United States or, alternatively, admitted.

Most if not all illegal entrants have no claim to lawful admission, and their only “relief” from removal is requesting asylum. That’s why you will hear many use the term “asylum seeker” to describe any illegal migrant, even when the term is inapt or inapplicable.

Criminal Law Deterrents. Note that there is no criminal sanction that applies to aliens who are inadmissible under sections 212(a)(6)(A), 212(a)(6)(c), and 212(a)(7)(A) of the INA. The consequence for violating those provisions is removal from the United States, a strictly “civil” penalty.

Congress also, however, provided criminal penalties for those who enter illegally or attempt to enter fraudulently. Illegal entry is a misdemeanor under section 275(a) of the INA for a first offense (subject to six months’ imprisonment), and a felony (carrying a two-year sentence) for subsequent violations.

Visa fraud is a crime punishable as a felony under 18 U.S.C. § 1546 that can carry a sentence of 10 to 25 years.

Detention and Prosecution Pre-Biden. Prior to the Biden administration, illegal entrants were detained largely as a matter of course, subject to resource constraints. For example, in FY 2013 under the Obama administration, CBP encountered more than 448,000 migrants at the Southwest border, and detained nearly 366,000 of them (82 percent) until their cases were completed.

Under a problematic 2008 law, however, unaccompanied alien children (UACs) from “non-contiguous” countries who enter illegally are not subject to detention (they’re sent to the Department of Health and Human Services to be “sheltered” until they can be released to a “sponsor” in the United States), while a poorly reasoned 2015 district court decision bars DHS from holding children who have entered illegally with an adult in a “family unit” (FMU) for more than 20 days.

In the latter case, to avoid “family separation” the adults are usually released, as well.

Not surprisingly, throughout the Obama and Trump administrations increasing numbers of UACs and FMUs began crossing the Southwest border illegally, and the percentage of illegal entrants who were detained fell accordingly: to 57 percent in FY 2016; 54 percent in FY 2017; and 33 percent in FY 2019; before surging again to 66 percent in FY 2020 — largely due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which limited entries.

Prosecutions for illegal entries were not a focal point of Obama’s border strategy, but the administration did not shy away from them, either. In FY 2016, more than 35,000 aliens were charged with illegal entry under section 275 of the INA, for example, a year in which more than half of all federal criminal charges were immigration-related.

Those prosecutions really jumped under Trump, however, and in the month of June 2018 alone nearly 8,800 aliens were charged for illegal entry.

Those prosecutions coincided with the Trump administration’s short-lived “zero-tolerance” policy, pursuant to which DOJ directed its prosecutors to charge all aliens who had entered illegally — including adults in family units — with “improper entry” under section 275(a) of the INA.

Once that happened, their accompanying children were deemed “unaccompanied” UACs under that same 2008 law when their parents went into U.S. Marshals Service custody, leading opponents of the policy (and others) to complain that Trump was deliberately separating families.

In late June 2018, Trump ended prosecutions of most adults in FMUs, which spurred a surge in family unit migration. Nearly 474,000 aliens apprehended at the Southwest border in FY 2019 were in FMUs — almost 56 percent of all apprehensions that fiscal year, and a three-fold increase over FY 2018.

Biden’s Shift. Biden has done a 180-degree turn from the Obama and Trump administrations in using detention and prosecution as deterrents to illegal entries.

Complaints about Trump “separating families” were big Biden talking points during the 2020 presidential campaign, even well after zero tolerance ended, and once he became president Biden made quite the show of his efforts to reunite separated families — in the United States.

Biden did not stop there, however. Prosecutions for illegal entry — which had dropped under Trump thanks to CDC orders directing the expulsion of illegal entrants, issued pursuant to Title 42 of the U.S. Code starting in March 2020 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic — have remained low even as the number of aliens expelled under Biden pursuant to Title 42 has dropped.

In November 2022, just 21 aliens were charged with illegal entry under section 275 of the INA, while in that month alone, more than 105,000 illegal migrants were apprehended at the Southwest border and released on parole or on their own recognizance.

Which brings me to section 235(b), mandatory detentions of illegal entrants. The Biden administration has all-but unilaterally read that detention mandate out of the INA, choosing instead to release more than 1.8 million aliens apprehended at the Southwest border. (That's my estimate because DHS has refused to provide actual figures.)

Admittedly, the administration has the discretion to prosecute illegal entrants or not, but it has no authority — whatsoever — to release tens of thousands of them into the United States every month. Not surprisingly, therefore, the Biden administration’s border release policies are the subject of two separate lawsuits, one in Texas (Texas v. Biden) and one in Florida (Florida v. U.S.).

The Global Surge. Because there are no consequences for entering the United States illegally at this time, nationals of countries worldwide are now coming to the United States, and entering illegally at the Southwest border.

Judge Robert Summerhays, who stayed the Biden administration’s attempt to end Title 42 in response to a challenge by state plaintiffs (in Louisiana v. CDC) has directed CBP to submit monthly disclosures detailing the number of illegal entrants apprehended at the Southwest border who have been expelled under those CDC orders and the number who have been processed instead under the INA, by nationality. The responses are revealing. Here are just a few:

- Afghanistan: 470 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Angola: 89 apprehensions, one expelled under Title 42.

- Armenia: 36 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Azerbaijan: 27 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Bangladesh: 166 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Burkina Faso: 82 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- People’s Republic of China: 848 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Dominican Republic: 8,427 apprehensions, two expelled under Title 42.

- Eritrea: 148 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Georgia: 822 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- India: 2,481 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Iran: 21 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Kyrgyzstan: 110 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Mauritania: 213 apprehensions, one expelled under Title 42.

- Nepal: 310 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Romania: 69 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Russia: 912 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Somalia: 26 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Sri Lanka: 61 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Turkey: 913 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Uzbekistan: 513 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

- Vietnam: 218 apprehensions, none expelled under Title 42.

Those are just 22 of the 106 countries represented in the Border Patrol apprehension disclosures in Louisiana in the month of December alone. In total, they account for nearly 17,000 apprehensions.

There is no way for the administration to address the “push factors” prompting nationals of all those countries to leave home and travel to the United States. The only way to prevent their entries is to negate the pull factors, the most significant of which is the opportunity to live and work in the United States for up to a decade while their asylum cases wend their way through the courts.

The only way the Biden administration can achieve and maintain operational control at the Southwest border is to use the tools that Congress has given it (and in the case of detention, required it to use). The United States government can’t really control events in Sri Lanka and Uzbekistan — but it can make the right decisions at the U.S.-Mexico line, and it’s time for Biden to start doing so.