CBS News reported this week that the Biden administration will allow foreign national parents to return to the United States to “reunite” with children here who were separated from them under the Trump administration’s short-lived 2018 “zero tolerance” policy. The reporting leaves out a lot, and raises a lot more questions than it answers, but that’s been true for a while.

To get to those unanswered questions, though, some background is necessary.

Civil and Criminal Penalties for Illegal Entry

Illegal entry is both a civil offense that subjects aliens to removal under at least two provisions in section 212 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), and a criminal offense under section 275(a) of the INA. First-time illegal entry is a misdemeanor (carrying a sentence of up to six months), while subsequent reentries are felonies (for which the offender can be fined and sentenced to two years).

Needless to say, the prospect of two years’ incarceration is a deterrent to repeat offenders, and between FY 2010 and FY 2016, about 21 percent of those who entered illegally were prosecuted.

Flores and the Surge of Illegal Migrants in “Family Units”

“Family separation” is a novel concept, because the entry of adult migrants with children in “family units” (FMUs) is a relatively new phenomenon.

In fact, Border Patrol only keeps records on apprehensions of family units going back to FY 2013, because before 2011, the vast majority of illegal entrants (more than 90 percent) were single adult males.

That said, however, there were some children who entered illegally before FY 2013. To govern the terms of detention and release of minors in immigration custody, DOJ and a class of plaintiffs entered into what is now known as the “Flores settlement agreement” in 1997.

That agreement was “originally applicable only to unaccompanied children” (UACs), as a report from a bipartisan federal panel explained in April 2019.

That all changed in August 2015, however, when U.S. District Court Judge Dolly Gee issued a decision finding that the Flores settlement agreement applied to accompanied children who had entered in “family units”, too, and required DHS to release those children from DHS within 20 days.

To avoid “family separation”, the parents and guardians who had brought those children to the United States were and are generally released, as well — although section 235(b) of the INA mandates their detention until they are granted asylum or removed.

Not surprisingly, the number of adults who entered the United States illegally with children in the hopes of quick release under Flores boomed after that decision was issued. In FY 2015, Border Patrol apprehended just fewer than 40,000 migrants at the Southwest border in family units; in FY 2016, after that decision was issued, there were almost 77,700 such apprehensions.

The inauguration of Donald Trump put a dent in illegal entries initially, and total CBP Southwest border “encounters” dropped 33 percent between FY 2016 and FY 2017.

In the absence of a congressional Flores “fix” and other amendments to close the loopholes encouraging illegal entries, however, apprehensions at the Southwest border soon rose across the board, and in particular apprehensions of migrants in family units.

CBP encounters at the Southwest border rose by just over a quarter between FY 2017 and FY 2018, but Border Patrol apprehensions of FMUs increased almost 42 percent (from 75,622 to 107,212) during that period. The number of FMU apprehensions in FY 2018 was — at that point — the highest in any year for which Border Patrol keeps statistics (again, back to FY 2013).

Illegal Entry Prosecution Pilot Program

From March to November 2017, the Border Patrol ran a pilot program to discourage illicit migration by increasing the number of criminal prosecutions for illegal entry. Notably, that pilot program allowed for the prosecution of adults who had entered in family units, and some 280 families were separated thereunder.

It was apparently successful, because in El Paso, Texas — one of the primary sites of that pilot — FMU apprehensions reportedly dropped by 64 percent.

“Zero-Tolerance” and “Family Separation”

Thereafter, on April 6, 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a “Zero-Tolerance Policy for Criminal Illegal Entry”, under which all aliens who entered illegally were to be prosecuted under section 275(a) of the INA.

Those aliens subject to zero-tolerance were passed from DHS to the custody of the U.S. Marshals Service (in DOJ) for prosecution.

Because children are not subject to prosecution for illegal entry — and are not detained in DOJ custody — however, the previously accompanied children in those FMUs became “unaccompanied children”, and were sent to Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) shelters under a 2008 law limiting their detention in DHS custody.

Due to public outcry over (and poor implementation of) that policy, President Trump ended it in an executive order (EO) captioned “Affording Congress an Opportunity To Address Family Separation” on June 20, 2018. That EO directed the attorney general to seek a modification of the Flores order to allow for the continued detention of family-unit migrants.

The July 2018 Flores Order, the Return of “Catch and Release”, and the Boom in FMUs

The day after that EO was issued, and in accordance therewith, DOJ filed an application for relief from the Flores settlement agreement.

Judge Gee denied that application in an order 18 days later in July 2018, deriding it as “a cynical attempt, on an ex parte basis, to shift responsibility to the judiciary for over 20 years of congressional inaction and ill-considered executive action that have led to the current stalemate.”

As I noted in July 2018: “The predictable result of that order has been a return to ‘catch and release’, as the New York Times bluntly put it, with the government freeing ‘hundreds of migrant families wearing ankle bracelet monitors into the United States.’”

I continued: “And the predictable result of the end of "catch and release" will be another influx of ... family units entering illegally.” Boy, was I correct: In FY 2019, Border Patrol apprehended almost 473,700 migrants in family units at the Southwest border, a more than 340 percent increase over the then-record number the year before.

Multiple Reasons for Separating Family Units

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) reported in February that between 5,300 and 5,500 children in family units were separated under the Trump administration (one of its calculations pinpoints the number as 5,349 between the March 2017 start of the pilot and November 30, 2020), but according to CRS, only 2,816 were separated during the brief period in which “zero tolerance” was in effect.

It explained that “almost all” of those children who were separated under zero tolerance “have since been reunited with their parents or placed in alternative custodial arrangements.”

Nonetheless, according to CRS, “[a]s of December 2020, a steering committee assembled to locate” children separated before and after zero tolerance “had not yet established contact with the parents of 628 children.”

Note that not all families at the border are, or historically have been, separated for prosecution alone.

CRS reports that in FY 2017, for example, CBP separated 1,065 families: 46 due to fraud and 1,019 due to medical and “security” concerns (including danger to the child and other criminal activity by the adult). In FY 2018, prior to Sessions’ zero-tolerance announcement, 703 families were separated: 191 due to fraud and 512 for medical or security concerns.

There were also 927 children separated from adults in FMUs in 2019, and 40 in the first 11 months of FY 2020. It is not clear from the CRS report why those separations occurred.

The Politics of Family Separation

As noted, “family separation” under zero tolerance was a Trump administration policy for less than two months, although it existed as a smaller pilot program before that. In any event, it appears to have been effectively ended as of Trump’s June 2018 EO.

Despite this fact, however, “family separation” as a political issue took on a life of its own, particularly during the “border emergency” in the spring and summer of 2019.

Between March and June that year, more than 50,000 migrant family units were apprehended by Border Patrol at the Southwest border per month (apprehensions reached almost 84,500 in May 2019), and the number of unaccompanied alien children surged as well, from 4,753 in December 2018 to 11,475 in May 2019.

As explained in the previously mentioned April 2019 report from a bipartisan federal panel, CBP was so overwhelmed, many migrants in family units were simply being released with a Notice to Appear (NTA, the charging document in removal proceedings), for asylum hearings that could take years to complete. That policy, the panel concluded, was “[b]y far, the major pull factor” encouraging other FMUs to enter illegally (it also found that the crisis was “exacerbated” by Flores).

Worse at the time was the fact that HHS had run out of shelter space, and therefore unaccompanied children were left in Border Patrol facilities (built for those single adult males I referenced earlier, not for children and not for any extended period of time) until shelter space became available.

On May 1, 2019, Trump asked for additional funding to deal with the situation (as I explained in a June 26, 2019, post captioned “If You Are Just Now Angry About UAC Detention, You Haven't Been Paying Attention”), but Congress stalled on providing it until late June (mainly due to objections from House Democrats, as I explained in July 2019).

In the interim, Trump’s opponents used the crisis as a campaign issue, with then-presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg (D) stating he “wouldn't put it past" Trump to allow the border “to become worse in order to have it be a more divisive issue, so that he could benefit politically.” Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) compared detention facilities to “concentration camps”.

The media did not help matters. A June 24, 2019, article in the Washington Post began: “The image kept replaying in attorney W. Warren Binford’s mind after she left a migrant detention facility last week in Clint, Tex., where hundreds of children were held: The 15-year-old mother, her baby covered in mucus.”

“Family separation” (which, as noted, had ended the previous year) became conflated with the “kids in cages” images from the border crisis (although the Trump administration did not do much to clear matters up).

The Biden Campaign and the Election Aftermath

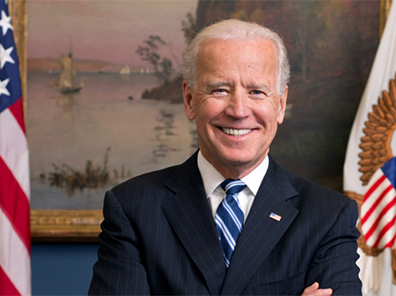

Then-candidate Joe Biden used the conflation of the issues to pummel the then-president, describing it on his campaign website as a “moral failing”:

When children are locked away in overcrowded detention centers and the government seeks to keep them there indefinitely. When our government argues in court against giving those children toothbrushes and soap. When President Trump uses family separation as a weapon against desperate mothers, fathers, and children seeking safety and a better life.

Thereafter, during the second and last presidential debate in October, moderator Kristen Welker brought up the fate of “more than 500 children”, the parents of whom, in Welker’s words “the United States can't locate”. She asked Trump: “So how will these families ever be reunited?”

As I explained in a post shortly thereafter, the actual number (at the time) was 545 children, and the Wall Street Journal reported on October 21 that “[a]s many as two-thirds of the[ir] parents, mostly from Central America, are thought to have been deported by U.S. authorities”.

That article quoted a Trump White House spokesperson, who explained that many “have declined to accept their children back”. Also quoted was a DHS spokesperson, who stated the department “has taken every step to facilitate the reunification of these families where the parents wanted such reunification to occur”. (Emphasis added.)

By December 2020, as noted, the number of separated children stood at 628 children according to CRS, the parents of 295 of whom “were likely deported”, and 333 of whom “were likely still in the United States”.

Family Reunification under the Biden Administration

In February, President Biden issued an EO establishing an “Interagency Task Force on the Reunification of Families”. He stated therein that his “administration condemns the human tragedy that occurred when our immigration laws were used to intentionally separate children from their parents or legal guardians ... including through the use of the Zero-Tolerance Policy.” (Emphasis added.)

That task force was directed to reunite families, and returning to the May 3 CBS News article, will start the process by bringing parents — who were apparently removed — back to the United States.

Questions

All of this raises the following questions:

- Of the parents who were separated from those 628 children, how many were separated for criminal prosecution alone, and how many (if any) were separated for: (a) medical reasons; (b) suspected fraud; or (c) because the parent or other adult (I) had a prior immigration record, (II) had a prior criminal record, or (III) was deemed to pose a danger to the child?

- Of the approximately 5,349 children who were separated from their parents or other adults between March 2017 and November 30, 2020, how many were separated for criminal prosecution of the parents or other adults alone, and how many were separated: because there was a suspicion of fraud; on medical grounds; because the parent or other adult had a criminal or immigration record; or because the parent or other adult was deemed to pose a danger to the child?

- If any children whose parents are being returned to the United States were separated due to suspected fraud, what steps has the Biden administration taken to verify the parental or familial relationship? Are DNA tests being performed?

- If any children were separated due to suspected danger to the child, what will the Biden administration do to ensure that child’s safety?

- On what status are those parents being allowed to return to the United States? Are they being allowed to return if they have criminal records — including for illegal entry and reentry — in this country? Will those parents be given employment authorization, and if so, on what basis? Will they be placed into removal proceedings?

- Who is paying to return those parents to the United States? Is it U.S. taxpayers, or the parents themselves?

- If the president “condemns” family separation, “including through the use of the Zero-Tolerance Policy”, will Biden allow children in family units to be separated from accompanying parents or adults where: there is a suspicion of fraud; the parent or adult poses a danger to the child; there is suspicion that the child has been trafficked; or the parent or adult has been convicted of an aggravated felony or other serious crime in the United States?

Inquiring minds want to know. The answers are crucial not only to border security and national sovereignty, but to the public fisc and the children who will be “reunited”.