According to the Washington Post, almost four months after Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas ordered the administration to restart the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), better known as “Remain in Mexico”, the administration is restarting MPP, beginning on December 6. It comes with a load of caveats and conditions, but at least it’s something.

Quick Recap of Remain in Mexico. To recap: MPP was instituted by the Trump administration in January 2019 in response to what then-DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen termed an “urgent humanitarian and security crisis at the Southern border”.

The program was enacted in accordance with section 235(b)(2)(C) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which allows DHS to send illegal migrants (and other inadmissible aliens) back across the border to await removal proceedings.

As I explained in a November 4 post, the program was enjoined shortly after it was implemented, but then that injunction was stayed and MPP got up and running, only for it to be enjoined again by the Ninth Circuit in February 2020. The injunction was stayed once more, this time by the Supreme Court that March. And then, the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

When Remain in Mexico was in full effect, however, it worked. Border Patrol apprehensions at the Southwest border fell to just over 40,500 in September 2019, from nearly 133,000 just four months prior. Apprehensions kept dropping and remained low until the pandemic shut down most cross-border traffic throughout the world in March 2020.

In an October 2019 assessment of the program, DHS described MPP as “an indispensable tool in addressing the ongoing crisis at the southern border and restoring integrity to the immigration system”, particularly as related to alien families. Asylum cases were expedited under the program, and MPP removed incentives for aliens to make weak or bogus claims when apprehended.

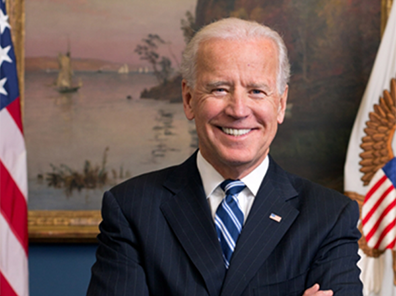

Nonetheless, then-candidate Joe Biden railed against the program on the campaign trail, and one of the first things he did in office was to halt new enrollments in MPP. Migrants who were still in the program were allowed to proceed into the United States starting in February, and DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas terminated the program in June.

Court-Ordered Reinstatement of MPP. Well, Mayorkas tried to terminate it, at least. The states of Texas and Missouri challenged his June rescission of MPP in federal court in Texas, and on August 13, Judge Kacsmaryk enjoined the Biden administration’s termination of MPP.

The president unsuccessfully sought to have that injunction stayed, first in the Fifth Circuit and then before the Supreme Court, which issued a brief order denying his request for a stay on August 24.

Biden’s Version of Remain in Mexico. That left the administration with few options except to restart Trump’s most successful border-control program, but it certainly took its time doing so. The Mexican government initially balked at agreeing to accept the third-country nationals who are subject to Remain in Mexico, but as the Post reported, it has finally agreed to do so — with conditions.

The paper explains:

“Mexico has demanded a number of humanitarian improvements as conditions of agreeing to accept enrollees,” said one U.S. official, including guarantees that asylum seekers will have access to legal counsel and that their humanitarian claims will be processed within six months.

And aliens enrolled in MPP are to be offered Covid vaccines — Johnson & Johnson for adults and Pfizer for eligible children — to be administered by contractors in Border Patrol facilities. There is not a “vaccine mandate” imposed on those migrants, but they must be offered vaccination.

That raises the question of how long those migrants will remain in the United States before they are sent back to Mexico. As we all likely know by now, Johnson & Johnson is a one-shot regime, but Pfizer requires two shots, administered 21 days apart.

Does that mean that adult aliens and children traveling in family units will be allowed to spend three weeks in the United States before heading back across the border, or will the family be allowed to return to the United States for the second dose? The Post does not say.

What the Post does assert, however, is the following: “The Trump administration used the MPP program to return more than 60,000 asylum seekers across the border to Mexico, where they were often preyed upon by criminal gangs, extortionists and kidnappers.” (Emphasis added.)

There have been more than a fair share of articles asserting that MPP migrants have been targets for crime in Mexico (conditions there are the primary reason Mayorkas offered for his latest attempt to end MPP, issued on October 29, and to be implemented if and when the pending litigation is completed), but I have never seen any official studies on the frequency of such offenses.

The Post reports, however, that New York-based NGO Human Rights First has “recorded at least 1,544 ‘violent attacks’ against migrants returned to Mexico under the program.”

Any attack, violent or otherwise, is unacceptable, but crime occurs in Mexico, and often at a higher rate than in most places in the United States (although my erstwhile hometown of Baltimore, where more than 11,000 violent crimes occur annually, is sadly an exception). The Post’s seemingly implicit attempt to blame criminal attacks on MPP enrollees on Trump appears to be misplaced, however.

As DHS explained when it first implemented MPP, Mexico had agreed to provide those third-country nationals “with all appropriate humanitarian protections for the duration of their stay”. The Post denies that ever occurred, however, reporting that during MPP’s first go-round, “Mexico did little to assist or protect the tens of thousands of migrants who waited for their asylum claims to be processed.”

In that vein, however, the Post reports that court filings reveal that this time, “Mexico will ensure MPP enrollees are provided temporary legal status and work permits, and will have access to shelters and safe transportation to and from the border to attend their court hearings”.

Restrictions on the Class of Migrants Subject to the New MPP. MPP will initially be used to return single adult migrants, but the Post indicates that expulsion under CDC orders issued pursuant to Title 42 of the U.S. Code in response to the pandemic will be the Biden administration’s “primary border management tool”.

It is not clear whether the current iteration of Remain in Mexico will be expanded to include migrants in family units, nor is it clear what nationalities will be included.

According to the Post, the Mexican government has agreed to accept nationals of Spanish-speaking countries (which would exclude Haitians and Brazilians, at a minimum), but an unnamed administration official told the paper that all nationals of Western Hemisphere countries would be subject to MPP. In either case, MPP would not be applied to "extra-continental" migrants.

The Biden administration will further trim down the class of aliens eligible for the program by excluding unspecified “most vulnerable migrants”, and ostensibly its plans include additional questioning of those who may be returned to determine whether they also fear persecution or torture in Mexico.

How Asylum Claims Will Be Heard. The federal government has designated 22 immigration judges to hear those aliens claims to comply with the 180-day asylum adjudication deadline (which is also mandated in section 208(d)(5)(A)(iii) of the INA, but rarely met outside of detention), and MPP removal hearings will be held in the Texas cities of Brownsville, Laredo, and El Paso, as well as in San Diego.

What’s in It for Mexico, and a Curious WaPo Admission About “Root Causes”. If you are wondering why, exactly, the Mexican government would agree to accept the return of any third-country nationals under MPP, the Post offers a clue, explaining:

It appears that one U.S. concession that swayed Mexico was Wednesday’s announcement of a joint U.S.-Mexico development program in Central America, called Sembrando Oportunidades, or Planting Opportunities, a variation on a pitch that Mexico’s president had been making — unsuccessfully — to Washington for years. The program, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development, aims to address the root causes of migration through increasing employment opportunities and promoting good governance. Such efforts have shown little evidence of deterring migration in the short term.

Curiously, those are the same proposals that Vice President Kamala Harris has been peddling in her role as “border czar” to address the migrant crisis at the Southwest border for some months now, but I do not recall the Post noting in connection with the vice president’s efforts that they “have shown little evidence of deterring migration in the short term”.

Nonetheless, the paper’s assessment is plainly correct, although I would note that these ideas have been tried before (including by Biden when he was vice president), and they have never shown much evidence of deterring migration in the long term, either.

Kudos to the Biden Administration — and to the Courts and States. All of this said, kudos to the Biden administration for finally pushing MPP up to the start line — again. The Southwest border is a disaster — with Border Patrol apprehensions there running at all-time highs, and hundreds of thousands of aliens evading agents and entering the United States — with unknown and potentially dangerous intentions.

And kudos to Judge Kacsmaryk and the states of Texas and Missouri for giving it the impetus to do so. MPP will likely be the only tool that the Biden administration employs to address the ongoing national security and humanitarian disaster at the Southwest border.