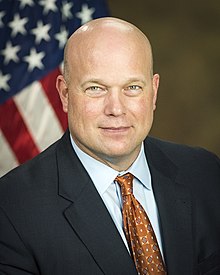

In a December 5, 2018, post, I talked about how acting Attorney General (AG) Matthew Whitaker had picked up where former AG Jeff Sessions left off in certifying to himself a case involving the effect of drunk-driving convictions on applications for cancellation of removal for certain nonpermanent residents. Certification is a powerful tool for setting immigration policy, but one that has been largely ignored in recent administrations until AG Sessions revitalized it. Last week, the acting AG utilized that authority again, this time in a case involving family-based asylum claims.

In a November 5 post, I discussed the need for the president to send immigration judges to the border to address the inevitable asylum claims that will be made by members of the caravan of Central American migrants, who are now in Tijuana. Included in that post was the following excerpt:

[A]sylum cases involving minors and families with minors are generally more complicated than cases involving single male adult aliens, a point that I made in my July 2017 Backgrounder, "The Massive Increase in the Immigration Court Backlog, Its Causes and Solutions". This fact will still be true notwithstanding the attorney general's efforts to clarify the asylum standards as they relate to claims based on private criminal activity in Matter of A-B-.

Specifically, I have recently been told that applicants have been converting claims that would otherwise be barred by that decision into claims premised on familial relationships to targeted individuals, such as the parents of males targeted for gang recruitment. The minors in question can then "ride" on the parents' asylum applications.

In Matter of L-E-A-, the BIA recently reiterated that family may be a "particular social group" for purposes of asylum under section 208 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). It held, however:

[M]embership in such a group does not necessarily establish a nexus to a ground protected under the Act. Rather, the respondent must demonstrate that the family relationship is at least one central reason for the claimed harm to establish eligibility for asylum on that basis.

Such determinations are fact-based, however, and are therefore time-intensive because they require the consideration of significant evidence, both country-conditions evidence as well as applicant testimony and documentation.

It is that latter case, Matter of L-E-A-, that the acting AG is taking on certification.

The facts in the case as described by the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) are fairly straightforward, and are not uncommon in asylum claims.

The applicant there had returned to Mexico under a grant of voluntary departure, and went to live with his parents in Mexico City. Prior to his return, "members of La Familia Michoacana [LFM], a criminal cartel, had approached the respondent's father, who owned a store that sold groceries and general merchandise in the neighborhood." LFM wanted to sell drugs from the applicant's father's store, because they thought it was a good place to do their illicit business. The father, on an unspecified date, refused, apparently without incident.

After the applicant returned to Mexico, he was approached by individuals in a car who identified themselves as members of LFM, and who asked him if he wanted to sell drugs at his father's store, again because it was a good location for the drug trade. He refused, and the LFM members advised him that he should reconsider their offer.

A week later, the applicant was approached by the same car, and four masked individuals attempted to abduct him. He escaped, and thereafter entered the United States illegally. As the BIA explained it:

Members of [LFM] contacted the respondent's father and claimed to have kidnapped the respondent, which his father was able to confirm was untrue. The respondent's father still operated the store, but he began paying "rent" to [LFM], which made it no longer profitable. The respondent's family members who live in Mexico, including his parents, have not been subjected to additional incidents of harm.

In the underlying matter, the BIA found that the applicant was a member of a particular social group of his father's family members, but held: "The key issue we must consider is whether the harm he experienced or fears is on account of his membership in that particular social group."

It continued:

An asylum applicant's membership in a family-based particular social group does not necessarily mean that any harm inflicted or threatened by the persecutor is because of, or on account of, the family membership. ... A persecution claim cannot be established if there is no proof that the applicant or other members of the family were targeted because of the family relationship. ... If the persecutor would have treated the applicant the same if the protected characteristic of the family did not exist, then the applicant has not established a claim on this ground. ... Moreover, under section 208(b)(1)(B)(i) of the Act, membership in the particular social group must be "at least one central reason" for the persecutor's treatment of the applicant. ... The protected trait, in this case membership in the respondent's father's family, "cannot play a minor role" — that is, "it cannot be incidental [or] tangential ... to another reason for harm."

Interestingly (and inventively), the BIA referenced the murder of the last czar of Russia, Nicholas II, and the rest of his family, holding: "This is a classic example of a persecutor whose intent, for at least one central reason, was to overcome the protected characteristic of the immediate family." I would concur with that assessment.

The BIA then stated:

However, if animus against the family per se is not implicated, the question becomes what motive or motives cause the persecutor to seek to harm members of an individual's family. In other words, is the persecutor's motive for harming the applicant his or her family status or another factor? The answer to this question depends on the reasons that generate the dispute.

To its significant credit, the BIA undertook a fulsome examination of case law in concluding that the immigration judge had correctly determined that the applicant "was targeted only as a means to achieve the cartel's objective to increase its profits by selling drugs in the store owned by his father," concluding:

Therefore, the cartel's motive to increase its profits by selling contraband in the store was one central reason for its actions against the respondent and his family. Any motive to harm the respondent because he was a member of his family was, at most, incidental.

…

It is significant that the cartel directly asked the respondent to sell their drugs in the store. This act bears no tie to an enumerated ground but is rather a direct expression of the cartel's motive to increase its profits by selling contraband in the store. Accordingly, the Immigration Judge's finding that the gang was not motivated to harm the respondent based on family status is not clearly erroneous.

For reasons are not entirely clear from the decision, however, the BIA remanded that matter to the immigration court for a fuller consideration of the applicant's claim under Article 3 of the Convention Against Torture.

In his order, the acting AG directed the parties and interested amici to brief the following issue:

Whether, and under what circumstances, an alien may establish persecution on account of membership in a "particular social group" under 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42)(A) based on the alien's membership in a family unit.

The underlying BIA decision was well-reasoned for the reasons set forth, so there does not appear to be any reason for the acting AG to disturb that decision per se. Rather, the only reason for the acting AG to issue a decision in this matter is to establish a bright-line rule for use in cases where, as I noted above, applicants have been converting claims that would otherwise be barred by Matter of A-B- into claims premised on familial relationships.

Since the BIA was relying upon historical precedent from the Russian revolution in its decision, the acting AG may want to reference American history in his analysis, and in particular the Lindbergh kidnapping. As the FBI describes that case:

Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., 20-month-old son of the famous aviator and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, was kidnapped about 9:00 p.m., on March 1, 1932, from the nursery on the second floor of the Lindbergh home near Hopewell, New Jersey. The child's absence was discovered and reported to his parents, who were then at home, at approximately 10:00 p.m. by the child's nurse, Betty Gow. A search of the premises was immediately made and a ransom note demanding $50,000 was found on the nursery window sill. After the Hopewell police were notified, the report was telephoned to the New Jersey State Police, who assumed charge of the investigation.

The body of the infant was found two months later in a shallow grave, the victim of a blow to the skull.

In that instance, the victim-infant was not subject to "persecution" on account of his membership in a particular social group, that is the family of Charles Lindbergh. Rather, his abduction (and likely murder) was part of a ploy to obtain ransom money, and monetary gain was the only reason for his kidnapping. There was no evidence in that case, whatsoever, that the kidnapper (Richard Bruno Hauptmann) bore any animus toward Charles Lindbergh Sr. or his family.

Similarly, most of the harm threatened and/or inflicted in cases involving criminal organizations (including gangs) in many asylum claims is the criminal end itself, not persecution on account of membership in a particular social group. Thus, for example, where a parent is threatened in order to coerce a child to join a gang, the sole reason for the threat is to increase the membership (and thereby the power and reach) of the gang, not because of the familial relationship.

The same is true of a case where a family member is threatened in order to obtain information about the whereabouts of a specific individual. The purpose of the threat, absent more, is to locate the individual in question, not to harm the individual threatened because of the relationship.

Given the tragic nature of these claims, they are difficult cases to decide. The asylum laws of the United States, however, are strict, and should be strictly enforced.

For third-country nationals in Mexico, applying for asylum in that country makes significantly more sense. First, as the Los Angeles Times reported in July 2018, the odds of receiving asylum in Mexico are better, and cases move more quickly:

In 2017, 64% of completed cases won protection, up from 37% in 2013. Petitioners may have to wait three or four months to have their cases resolved, but that's nothing. In the United States, upwards of 715,000 cases are backlogged in the immigration court system. Asylum claims can take six years or more to adjudicate, and approval rates for applicants from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador are extremely low.

Second, and likely relatedly, Mexico's asylum law is broader than the asylum laws in the United States, at least on paper. According to the San Diego Union-Tribune:

Asylum law in individual countries is generally based on the Refugee Convention of 1951, which Mexico signed in 2000. That international treaty is the basis for U.S. law that defines asylum seekers as those fleeing persecution because of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.

Mexico's legal definition, published in 2011, also includes people whose life, liberty or security are in danger because of generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflict or major human rights violations.

In 2016, Mexico added protections in its Constitution saying that anyone entering the country has the right to request asylum.

The paper notes, however, that asylum applicants in Mexico have only limited period of time (30 days) to file asylum applications, and that: "Certain groups of people — including the LGTBQ community, people with indigenous heritage, and foreigners in general — frequently report persecution in Mexico and seek asylum from Mexico itself." Moreover: "Some Central Americans report being followed by the gangs they fled back home through Mexico." While these facts would apply in certain cases, the remainder would appear to be good candidates for asylum in Mexico.

Finally, there have been human rights violations in Mexico and failures to follow the asylum process, as the San Diego Union-Tribune notes. As my former colleague Kausha Luna reported in an April 2018 post, however:

Recently, a UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) representative in Mexico, Mark Manly, told Mexican news outlet El Universal that the increase in asylum applications in Mexico can be expected to continue. ... The UNHCR representative added, "Despite the significant increase in the number of asylum applications, for a country like Mexico, they are still easily manageable figures, taking into account the size of the population, the economy, and the administrative capacity it has."

To summarize: The acting AG has taken up where AG Sessions left off, in using his certification authority to set immigration policy. In particular, he appears to be using that authority to respond in real time to a conversion of asylum claims from those based on direct harm to those based on harm on account of membership in familial relationships. As the asylum laws of the United States become clearer and better refined, it will likely be in the interests of third-country nationals to seek asylum in transit countries, including Mexico.

According to CNN, the president has just announced that William Barr, the 77th attorney general of the United States, is his choice to be the 85th attorney general of the United States. Let's hope that AG Barr continues the work of his immediate two predecessors in using his office to ensure that valid asylum claims are heard quickly, but that legally insufficient or frivolous claims are disposed of in short order.