"How come the EB-5 moneys, that are supposed to be used in depressed areas, all go to the glitziest parts of town?"

The puzzled voice at the other end of the phone was a Los Angeles reporter who was writing on the immigrant investor (EB-5) program, which was being used to fund a luxury hotel project. EB-5 (for employment-based, fifth class) gives alien investors and their families a full set of green cards in exchange for half-million-dollar investments in depressed areas of the United States if the money is used in so-called "targeted employment areas" (TEAs).

The reporter's question was a good one. The targeted areas, with the bargain-rate investment level of a half-million dollars, must, by law, have unemployment rates at least 150 percent of the nation's unemployment rate. One might assume, because of the math involved, that most of the United States would be out-of-bounds for the EB-5 program, yet something like 98-99 percent of the EB-5 visas are issued at the half-million level, with a tiny number going to investors in other, not-so-depressed areas at one million each. Why is this the case?

My response to the reporter was that Los Angeles hotels had no monopoly on this phenomenon, that USCIS was perfectly happy to accept oddly drawn TEAs, and that the legislation was written in a loose enough way to let the agency do that. The question, however, set in motion a thought process.

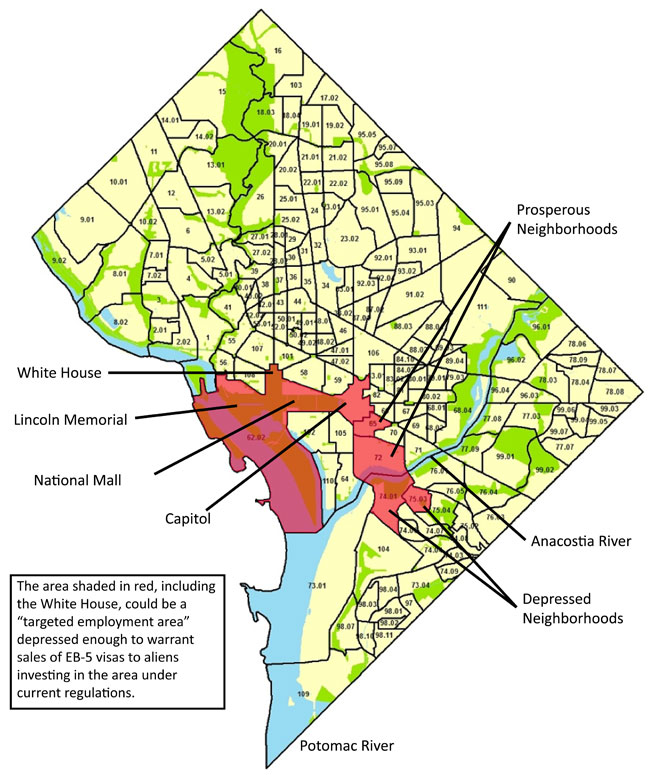

To wit: Could one create a TEA in downtown Washington, D.C., that included the White House or the Capitol and still meet the depressed area standards of USCIS? The White House, after all, is one of the grandest single-family dwellings in the nation. And, if such a TEA-creation could be done, how difficult would it be to pull it off?

I am neither a demographer nor a statistician nor a cartographer, and my computer skills are not equal to those of your typical 12-year-old, so the prospect of such manipulation seemed daunting at first.

While I had a basic idea of how all this worked, I needed more precise information. First, I used Google to look up the rules for creating TEAs. There was a helpful how-to article by Kate Kalmykov, an immigration lawyer, and another one from the California Governor's Office, both written from the point of view that the EB-5 program was manna from heaven.

From Governor Brown's office I learned:

- Projects can receive an EB-5 Special TEA certification if they are located within an area of twelve or fewer contiguous Census Tracts with a total average unemployment rate of 150% the national average.

- Requests for a special TEA should include a table listing each census tract with its corresponding unemployment rate and a map showing the project address.

- A supporting letter from the local Economic Development Corporation (EDC) or County or City in which the project is to be located must be provided. The letter must indicate the economic development corporation's concurrence that the proposed census tract will reasonably be a source of workforce for the project.

From Ms. Kalmykov I learned, but was not surprised to hear, that: "USCIS has also stated that they will accept the aggregation of contiguous census tracts commonly referred to as 'gerrymandering' to create a high unemployment area if accompanied by a state designation."

With those concepts in hand, I turned to the District of Columbia, whose geography is well known to me.

Clearly I needed two ingredients: 1) a census tract map of the city, and 2) 2010 census data on the unemployment levels for each of the tracts. A census tract, by the way, is a fairly stable entity, not changing much over the decades and usually containing at least several thousand people — sometimes only a few square blocks of a city, sometimes much larger chunks of suburban or rural geography.

The census tract map came easily and part of it can be seen below, but it took me a quarter of an hour to find unemployment data at the census-tract level, which turned out to be nearby.

The first thing I noticed from these sources was that there was a very large census tract in the middle of the map that covered both the White House and the Capitol, and the park-and-mall parts of downtown Washington; this is tract 62.02. I also discovered that 178 of the 179 tracts in Washington had more than 100 residents, with 62.02 being the exception; further, data were provided on population, poverty, unemployment, etc. in all the tracts with more than 100 residents, but not in the remaining one, so that the data on the family in the White House and the few other (if any) residents of 62.02 are kept secret.

All that was a distraction from my mission: Could I carve out a properly depressed TEA that included the White House? The answer was yes, and the whole process, once the basic data was in hand, took several whole minutes.

In order to create the economic gerrymander I picked two reasonably prosperous census tracts (65 and 72) just south of, and adjoining, the Capitol, with 72 fronting on the Anacostia River. That body of water is a dividing line between prosperous and non-prosperous parts of our nation's capital. Having reached the river, I added census tracts 74.01 and 75.03 on the other, depressed, side of the Anacostia. I now had a set of five contiguous census tracts that I thought might meet EB-5 standards. I then I checked on the unemployment levels of my newly created "econo-mander" and it came out like this:

Targeted Employment Area Including the White House: A Simulation

| Census Tract in DC | Population | Unemployment Rate, 2010 |

| 62.02 (inc. the White House) | < 100, say 99 | not known, say 0 percent |

| 65, next to Capitol Hill | 2,531 | 3.8 percent |

| 72, next to tract 65 | 2,794 | 5.5 percent |

| 74.01, next to 72 and east of the Anacostia River | 2,414 | 26.0 percent |

| 75.03, next to 74.01 and east of the Anacostia River | 2,425 | 26.0 percent |

| Five contiguous census tracts | total (about) 10,290 | average, either 12.3 percent or 14.7 percent, see text |

| Sources: Data from the U.S. Census Bureau; simulation by the Center for Immigration Studies. | ||

What neither set of instructions did was to tell me how to average the unemployment rates in the designated area. Should one use a raw average of the census tracts, or should one use a weighted average giving more statistical significance to the tracts with larger populations than the ones with smaller ones? In most EB-5 cases, that question would make little difference, as census tracts are roughly similar in population, but with the White House tract having so few people in it, and presumably a zero percent unemployment rate, the averaging methodology variable suddenly becomes an important one.

So, to be safe, I calculated both the raw average at 12.3 percent and the weighted average at 14.7 percent; both are considerably above 10.8 percent (150 percent of the nation's current unemployment rate of 7.2 percent).

The resulting map meets the program definitions, even though the people in it are all in the lower right-hand corner of the TEA, and the White House is in the upper left. Odd-shaped, to be sure, but it would serve to allow an EB-5 project to be mounted anywhere within its lines.

Bear in mind that I did this with only five census tracts, but could have used seven more tracts if the California rules apply nationally. And given the unemployment rates in the census tracts on the east side of the Anacostia, I could have created a TEA for the White House area with an average unemployment rate approaching 20 percent.

All the DC-area line drawing took less time to do than to write about it, so those developers who want to use EB-5 moneys to build a Taj Mahal in the heart of a very high-income district need not worry about the targeted employment area rules; they (or their white collar flunkies) can create a USCIS-acceptable TEA in less than an hour.

I write this not only to reply more fully to the LA reporter, but also to show yet another example of how loosely written congressional language can be elaborated upon by the Executive Branch to make it easier for ever larger flows of immigrants to take place.

If prosecutorial discretion means that few aliens are, in fact, prosecuted, then regulatory discretion, such as this economic gerrymandering, can mean that many more aliens, in fact, will be admitted.

The White House targeted employment area is just another example of how our immigration laws can be reshaped by a creative administration.