A lot has been said about the terrorist attack perpetrated by a Somali refugee in Ohio last Month. President-elect Trump visited Ohio State University last week, telling crowds afterwards at a rally in Des Moines that the attack was "a tragic reminder" of the need to take a hard line on immigration. I have a couple of things to add on the subject (including an overview of the Somali refugee community in the U.S at the end of this blog post). But first, a brief recount of what we know.

On November 28, Abdul Razak Ali Artan, an 20-year-old (or maybe 18; it's unclear) Somali national, drove his car into a group of students at Ohio State University then started stabbing people before he was shot by a police officer.

Artan was born in Somalia, he moved to Islamabad, Pakistan, with his family in 2007. In 2014, he, his mother and six siblings were admitted to the United States as refugees. In 2015, he became a permanent resident of the U.S. (green card holder). Some say his father works and lives in Dubai, others claim he never left Somalia. What is certain is that his father did not come to the United States.

Abdul Razak Ali Artan was enrolled at Columbus State Community for two years then started at Ohio State University in August 2016. In an interview for an Ohio State campus publication, he complained about American misconceptions about Islam and explained how his biggest struggle on his first day on campus was finding a place to pray. He missed Columbus State, where prayer rooms were available, adding: "we Muslims have to pray five times a day". He also spoke about how much he enjoyed life in Pakistan, and denounced Western misconceptions about this country.

First, and as my colleague Dan Cadman asked, why did we accept the Somali refugee and his family "rather than leaving them in Pakistan"?

By United Nations standards, resettlement to a third country is to be considered only "in situations where it is impossible for a person to go back home or remain in the host country." (Emphasis added.) Moreover, refugees in need of resettlement are the ones who are the most vulnerable, such as victims of torture or extreme trauma, or those in need of special care they cannot find in their country of refuge. The U.S. State Department is also crystal clear: "The U.S. resettlement program serves refugees who are especially vulnerable; those who…cannot safely stay where they are or return home." (Emphasis added).

What is not clear is how the Somali refugee and his family were "especially vulnerable" and why it was "impossible" for them to remain in Pakistan. A family friend in Pakistan described the young attacker's life there: "he completed an advanced program at a top high school. He prayed five times a day and played cricket." By his own account, Abdul Razak Ali Artan enjoyed life in Pakistan very much.

Why couldn't they safely stay where they were? What we know for sure is that, had they stayed there, terror would not have struck Ohio State University on November 28, 2016.

What is also evident is that the refugee resettlement program should not defeat its purpose; it should not be randomly used to fill in spots, raise funds, or alleviate consciences.

Another point pertains to the security challenge posed by the refugee resettlement program. The absence of dependable screening measures for refugees coming from countries of national security concern led to calls for "extreme vetting," if not for a pause in the program altogether. Sure, vetting is elementary and should remain a top priority. But it only gives us a glimpse of the past and present; it doesn't secure the future.

In the particular case of Abdul Razak Ali Artan and his family, the screening was not flawed; if U.S. officials found nothing, it was probably because there was nothing to find. Radicalization came later for one of them.

Integration is key for migrants in general but more so for refugees who suffered a great loss. Failed integration can lead to alienation, resentment, and in extreme cases, radicalization. Real (or even perceived) unsurmountable differences in values, culture, and beliefs are perfect ingredients for a time bomb. The bomb could be triggered or simply inspired by terrorist groups like ISIS who prey on the weak and the frustrated.

So, yes, thorough background checks are crucial in providing valuable insights and keeping out people who shouldn't come here. Also true, a hard line on immigration is long overdue. But it should also include making sure those who are welcome here are able and willing to integrate. Simply put, one must love and respect America and every value it stands for to be able to come to America.

One final point. State Department officials, in a desire to reassure the American public, often stress the fact that refugees admitted here are mostly families, women, and children. It is true that these groups are different from migrant flows that recently made it to Europe that were disproportionately young, unmarried, unaccompanied, and male. But this doesn't mean that families pose no threat. Actually, Abdul Razak Ali Artan came to the United States with his mother and six siblings. No "unaccompanied man" joined in, not even the father. Terror ultimately came from one of the seven children.

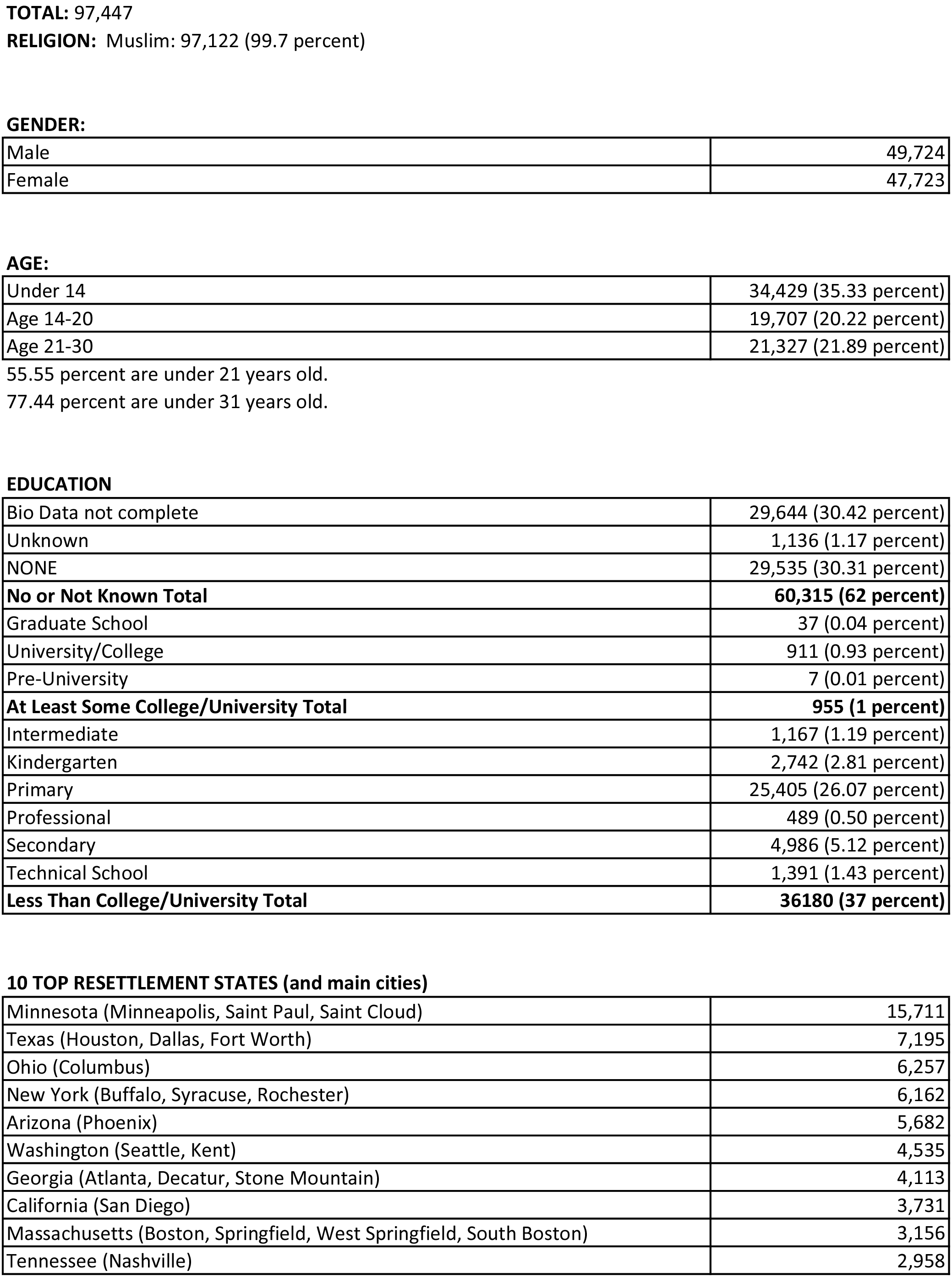

Demographic Profile of Somali Refugee Arrivals

October 1, 2000, through September 30, 2016

State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration's Refugee Processing Center

97,447 Somali refugees were admitted during that period. Most are Muslims (99.7 percent), rather young (77.44 percent are under 31 years old and 55.55 under 21 years old), with very little education (91 percent either primary or less; only 1 percent with some sort of college/university). The top five resettlement states are: Minnesota, Texas, Ohio, New York, and Arizona.

Update:

During the first two months of FY 2017 (October 1-November 30, 2016), another 2,463 Somali refugees were admitted (out of a total of 18,299 refugees). Somali nationals were the second largest group behind Congo nationals (4,236).