Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Nayla Rush is a senior researcher at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Summary

Nearly eight months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we can paint a picture of the millions of Ukrainians who fled their country. This report sheds some light on the profile and intentions of these Ukrainians, the type of protection they are signing up for, the destination countries they choose to settle in, and the perspectives of their return home or onward migration.

The key points:

- Around seven million Ukrainians have sought refuge across Europe since the Russian invasion, most of them women and children, since men aged 18-60 are not allowed to leave the country.

- Around four million have registered for “Temporary Protection” in the European Union, a status not available for the 2.5 million who sought refuge in non-EU countries.

- A small proportion are applying for asylum in the EU: only 25,100 asylum applications were submitted by Ukrainian nationals from February 21 to September 4, 2022.

- For a significant proportion of Ukrainian refugees, the temporary protection will not be so temporary, and the number of refugees will probably increase. Instead of a quick victory, the conflict is likely to develop into a stalemate and a protracted war that could last for years.

- The likely scenario includes limited possibilities for large-scale return to conflict-affected areas and possible new refugee flows.

- For now, most Ukrainian refugees are women and children, but this could change. Men will want to join their spouses outside Ukraine should the restrictions for this group be removed, or even in defiance of an ongoing mobilization. Departures of men could add significantly to the existing number of refugees.

- Ukrainians fled to neighboring countries, but many moved on to settle in other countries across Europe to join family and friends, which basically means that diasporas attract onward migration. Russia, Poland, and Belarus, but also Germany and Italy, were favorite destinations for Ukrainians before the conflict.

- When Ukrainians do return home, it is often temporary; there is back-and-forth movement to visit family, get supplies, or help other relatives to evacuate.

- Permanent return doesn’t seem to be on the agenda for most who left Ukraine: Only 10 percent of returnees from abroad have stayed. On the other hand, 5.5 million internally displaced Ukrainians returned to their homes. Most of those who left Ukraine come from provinces that are now mostly controlled by Russian forces.

- Factors such as the persistence of hostilities that undermine reconstruction attempts, the employment and integration capacities of the countries of refuge, and the economic situation in Ukraine itself determine the return or non-return of Ukrainian refugees.

- Research on re-migration patterns shows that “it is in fact women and children who have a relatively low probability of returning, especially the longer the war lasts and children put down roots at school.”

- The idea that “all Ukrainians want to return home” is not supported by data on migration intentions. Even prior to the February 24 invasion, one in four adults in Ukraine wished to migrate. The desired destinations were mostly in the EU, but non-EU countries such as the United States and Canada were also on the list.

- Pre-war migration desires were influenced by several factors: the continuing violence in the east of the country since 2014, the significantly lower living standards compared to countries in the European Union, severe inequality and persistent corruption, and the Ukrainian diaspora already working abroad.

- This original desire of one out of four to leave will undoubtedly influence the thinking of the millions of recent war refugees about whether to return should the opportunity arise.

- A United Nations report describing the profiles and intentions of refugees from Ukraine shows that among those planning to move to another host country, the large majority (75 percent) was planning to move to non-neighboring European countries, Germany being the most frequent reported destination with 27 percent. A small proportion wanted to move to non-European countries: Canada came on top of the list with 10 percent; only 2 percent reported wanting to move to the United States.

- To respond to the Ukrainian crisis, the U.S. Congress approved in May $40 billion in aid for Ukraine and other countries impacted by the conflict, the sixth aid package since the crisis began.

- $16 billion of this last package is directed toward humanitarian assistance, which includes $350 million for migration and refugee assistance to provide humanitarian support for refugee outflows from Ukraine.

- The United States underlined early on the importance of proximity help versus resettlement in the United States, both because the resettlement referral process takes time and because of the common belief that most who fled Ukraine want to stay close to home.

- Only 918 Ukrainians were admitted to the United States through the Refugee Resettlement Program from March through September 2022.

- The Biden administration designed a relatively easy and speedy pathway for Ukrainians to come here and provided them with a large array of benefits to help them integrate. Some 100,000 Ukrainians were admitted under this new program in just a few months.

- The U.S. bet that Ukrainians will want to stay close to home, hoping to be able to return as soon as possible, might not prove to be right in the long term.

- Europe is experiencing a serious setback to its strong yet incomplete recovery from the pandemic because of the war in Ukraine. It is facing a broad array of challenges, including welcoming and integrating millions of Ukrainians and dealing with rising energy prices.

- Ukrainians struggling in Europe might very well use the easy pathway designed by the Biden administration and join the growing diaspora here. The United States needs to be ready for such permanent guests.

Number of Refugees from Ukraine Recorded in Various Destination Countries Across Europe

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) data portal (as of October 11, 2022), the estimated number of individual refugees who have fled Ukraine since 24 February and are currently present in European countries totals 7,678,757.1 For statistical purposes, UNHCR “uses the term refugees generically, referring to all refugees having left Ukraine due to the international armed conflict.”2

Ukrainians fled to neighboring countries, but many moved on to settle in other countries across Europe.

Ukraine is bordered by Belarus to the north, Russia to the east, Moldova and Romania to the southwest, and Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland to the west.

The number of refugees from Ukraine recorded in these neighboring countries are as follows (figures are rounded; unless noted otherwise, all figures provided in this report are based on UNHCR’s data portal as of October 11, 2022): Some 16,000 Ukrainians sought refuge in Belarus, 2.9 million in Russia, 94,000 in Moldova, 82,000 in Romania, 30,000 in Hungary, 97,000 in Slovakia, and 1.4 million in Poland.

These numbers are just a portion of those who crossed over from Ukraine. Border crossings from Ukraine to Belarus totaled some 17,000, to Russia 2.9 million, to Moldova 650,000, to Romania 1.3 million, to Hungary 1.5 million, to Slovakia 850,000, and to Poland 6.8 million.

Apart from those who crossed over and settled in Belarus and Russia, many Ukrainians chose to continue their journey and settle elsewhere.

Factors Determining Onward Migration Flows of Ukrainian Refugees

Onward migration flows of Ukrainian refugees to various destination countries in Europe were recorded by UNHCR: one million refugees from Ukraine were recorded in Germany, 440,000 in the Czech Republic, 170,000 in Italy, 150,000 in Spain, 105,000 in France, 53,000 in Bulgaria, 83,000 in Austria, 53,000 in Portugal.

According to François Héran, director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), Germany is a desired destination for Ukrainians because of its economic prosperity and welcoming immigration policies.3 As for countries more to the south such as Italy, Spain, and Portugal, the Ukrainian diaspora is already present; and, as in most migration flows, people choose to go places where they have family members or acquaintances.

Researchers from the Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael) who have been monitoring Ukrainian migration flows in Europe since the invasion draw similar conclusions.4 They note that, with the absence of legal ground for distribution of Ukrainian refugees among EU member states, onward migration follows personal initiatives. Ukrainian refugees will tend to travel on to join family and friends, which basically means that the diaspora attracts onward migration.

A preview of onward migration flows can be drawn by looking at the distribution of the Ukrainian diaspora in numerous countries as it existed prior to the Russian invasion. There was an important Ukrainian diaspora presence in Russia, Poland, and Belarus in view of the geographical, cultural, and linguistic proximity. Germany and Italy were also on the list of favorite destinations for Ukrainians prior to the invasion as large economies with employment opportunities; resettlement programs for ethnic Germans in Ukraine played a role as well.5

Another important indicator for onward flows is the migration intentions of Ukrainians this past 10 years, before this recent conflict erupted. Researchers from the Swedish Delmi think tank used data from the Gallup World Poll on “Ukrainians’ willingness to move and preferred destination before the war” to assess how Ukrainian refugees will be distributed among various European countries.6

Findings show that Germany was the favorite destination for more than one out of three Ukrainians. Romania scored only 0.4 percent as a preferred country of destination for Ukrainians. Slovakia and Hungary also scored low as a preferred destination, which means that significant onward migration is expected from these three countries.

The UNHCR report referenced above confirms this point: Of the 1.3 million Ukrainians who crossed over to Romania, only 82,000 were recorded as refugees; of the 850,000 who crossed to Slovakia, only 97,000 were recorded as refugees; and, out of the 1.5 million who crossed to Hungary, only 30,000 were recorded as refugees.7

Returns to Ukraine: Permanent Return Does Not Seem To Be on the Agenda

Many Ukrainians who fled their country also chose to return home, although many of those returns are not permanent; they include back-and-forth movements to visit family or attend to business.

Permanent return doesn’t seem to be on the agenda for most who left Ukraine. As of June 28, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates that more than 5.5 million displaced Ukrainians had returned to their homes. Most of them had been internally displaced; only 10 returned from abroad.8

Border Crossings Out of and Into Ukraine

UNHCR calculated border crossings from and to Ukraine from February 24 to October 11, 2022:

- Border crossings out of Ukraine: 14 million.

- Border crossings into Ukraine (not counting from Russia and Belarus): 6.7 million.9

As UNHCR explained in a note, the data notes border crossings, not individuals (i.e., the same person may have crossed more than once) and includes both Ukrainians and third-country nationals.10 Also, “Movements back to Ukraine can be pendular and do not necessarily indicate sustainable returns as the situation across Ukraine remains highly volatile and unpredictable.”11

The breakdown of the 6.7 million border crossings into Ukraine is as follows: one million from Romania, 590,000 from Slovakia, 4.8 million from Poland, and 295,000 from Moldova. (Data was not available for border crossings to Ukraine from Hungary, Russia, and Belarus.)

Daily border crossings have fluctuated since the beginning of the conflict on February 24. A graph of daily exits and entries out and into Ukraine was drawn by a French news outlet that relied on UNHCR data.12 Here’s what it shows: The first weeks of the conflict saw some 150,000 people leaving Ukraine daily (with a peak of 190,000 departures on March 2) and only 10,000 entering the country. Six months into the conflict, daily exits totaled 40,000 versus 34,000 entries. There is still more movement out of Ukraine than into it, but the difference has noticeably shrunk.

Factors Determining the Return or Nonreturn of Ukrainian Refugees

According to the Clingendael Institute, multiple factors are at play in determining the return (or not) of Ukrainian refugees to their homes.13 There is obviously the actual possibility to be able to return in view of the intensity and duration of the fighting and the area occupied by Russia, but also the economic situation in Ukraine itself. Other factors are at play here: the extent of onward migration from the initial country of arrival to other European countries, the migration and return intentions of Ukrainians, and the integration realities of Ukrainians in the countries where they sought refuge.

The eastern area of Ukraine — which was the most densely populated area after Kyiv — is where some of the heaviest fighting has taken place. At the beginning of this crisis in February, “11.3 million people lived in the most heavily affected and by now occupied province of Luhansk and partially occupied provinces of Donetsk, Kharkiv, Zaporizhiya and Kherson.”14 The majority of the estimated seven million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 6.9 million refugees come from these provinces. Another 1.1 million Ukrainians were also considering fleeing the area.

Russia recently announced its formal annexation of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhziya, giving it control of over 15 percent of Ukrainian territory.15 And while both parties hope for a quick victory, “it seems more likely that the conflict will develop into a stalemate and a protracted war that could last for years.”16 Which means that many refugees will not want to return to an area occupied by Russia.

Moreover, with the persistence of hostilities that undermine reconstruction attempts, other refugees will not want to return either, but will keep traveling back and forth to Ukraine.

Women, for instance, will want to visit their husbands stuck in Ukraine by the state of emergency and general mobilization for men. Following a decree by President Zelensky, Ukraine is prohibiting men aged 18-60 from leaving the country in order to keep them available for military conscription.17 But things might change if the conflict continues for years. Men will want to join their spouses outside Ukraine should the restrictions be removed or even in defiance of an ongoing mobilization. Border crossings of men out of Ukraine, if they occur, could add significantly to the number of refugees. The likely scenario, as elaborated by the Clingendael Institute, is one toward “the limited possibilities for large-scale return to conflict-affected areas and of possible new refugee flows from Ukraine.”18

Other determining factors when it comes to the return of Ukrainians are employment and the integration capacities of the countries of refuge. As noted previously, the majority of Ukrainians who fled their country are women and children. A large number of these women have already found employment in their various hosting European countries. In the Netherlands, for instance, around 40 percent of all Ukrainian refugees were working in August.19

Moreover, research focusing on re-migration patterns teaches us that “it is in fact women and children who have a relatively low probability of returning, especially the longer the war lasts and children put down roots at school.”20

In any event, the idea that “all Ukrainians want to return home” is not supported by data on migration intentions, according to Clingendael researchers.21 They refer to a Swedish Delmi think tank study that used Gallup World Poll (GWP) data to show that, even prior to the February 24 invasion, one in four of the adult population in Ukraine wished to migrate:

During the years 2007–2021, slightly more than one fourth (26 percent) of Ukrainians stated that they had a desire to move to another country. This corresponds to about 12 million people. Of those expressing a wish to move, around half (47 percent) wanted to move to an EU country. Outside of the EU, the three most popular countries were the United States (15 percent), Russia (13 percent), and Canada (6 percent). In the current situation it is, however, most likely that most of those fleeing Ukraine will come to the EU. [Emphasis added.]22

The fact that Ukrainians wished to migrate before this crisis is understandable, notes Clingendael, in view of these factors:

the continuing violence in the east of the country since 2014, significantly lower living standards than in the European Union, severe inequality and persistent corruption, and at the same time the entrepreneurial spirit to work abroad as many before them were already doing.23

And, since a quarter of Ukrainians were already considering migration before the war, “it may be assumed that when the restriction on the departure of men is removed, part of the family reunion will take place towards Western Europe rather than in the other direction.”24

The “Temporary Protection” Granted in Europe Might Not Be So Temporary

Most of those fleeing Ukraine settled across Europe to join family and friends and/or seek job opportunities. Ukrainians have been Europe’s main economic migrants in recent years: 1.5 million in Poland alone, with the next largest groups in Germany, the Czech Republic, Spain, and Italy.25

To avoid overwhelming the standard asylum system and for faster protection rights, the European Commission decided on March 4, 2022, to give a “temporary protection” status to nationals of Ukraine and other eligible parties for an initial period of one year. This entails a residence permit, access to employment, housing, social welfare, medical care, education, legal custody and safe placement for unaccompanied children and teenagers, banking resources, guarantees for access to the normal asylum procedure, etc.26

This period, unless terminated, is to be extended automatically by six months for a maximum of one additional year; after which, the European Commission can either propose to end this temporary protection if it deems that Ukrainians can safely return home or, alternatively, ask for its extension by up to one additional year.

The European Commission announced it will extend the Temporary Protection until March 2024.27 Ylva Johansson, the European Commissioner for Home Affairs also said that those who decide to return home will not lose their status. Many were reluctant to go back home and lose their status because they were afraid they might need to flee again. Johansson explained: “So that’s why we have made the decision: it’s not necessary to deregister, only to notify that you are leaving the EU and going back home. So it’s important to notify but you can keep your card.”

But these changes might not lead to the desired objectives.

Clingendael researchers predict that, for a significant proportion of Ukrainian refugees, this "temporary" status will not be so temporary, and the number of refugees will probably increase. The likelihood that a significant proportion of the refugees will remain in EU countries for a longer period of time “means that a transition is needed from crisis management and a short-term orientation to more long-term policy and planning for structural capacity and support, both at European and Member State level.”28

Asylum Applications of Ukrainians in Europe

Most Ukrainians who fled their country recently did not apply for asylum despite the fact that they could have done so in the EU country of their choosing. Due to these exceptional circumstances, Ukrainians are exempt from the Dublin regulation limitations. The Dublin regulation stipulates that the EU member state in which an asylum seeker arrives is where the asylum application has to be submitted.

According to the latest protection trends released by the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), some 25,100 applications for asylum were submitted by Ukrainian nationals in the EU+ countries (EU+ refers to the 27 European Union member states, plus Norway and Switzerland) from February 21 to September 4, 2022.29

Countries of Registration for “Temporary Protection”

Ukrainians are almost exclusively registering for temporary protection in Europe; there were over four million registrations for temporary protection by the end of August.30

Ukrainian nationals are visa-free travelers in Europe and, as such, can choose the EU member state in which they want to exercise the rights attached to the temporary protection status, allowing them to join family and friends in various EU countries. This does reduce the pressure on frontline states such as Poland and Hungary. That said, the status cannot be used as a blank check; Ukrainians can exercise the rights deriving from it only in the EU member state that granted them the residence permit.

Note that this temporary protection status is not available for the 2.5 million Ukrainians who sought refuge in non-EU countries (Russia: 2.9 million; Turkey: 145,000; Moldova: 94,000; Georgia: 27,000; and Belarus: 16,000)

Ukrainian refugees do not automatically apply for “temporary protection” in the first country they fled to. As discussed earlier, migration intentions and preferred destination countries (such as Germany) do play a role in pushing for onward migration.

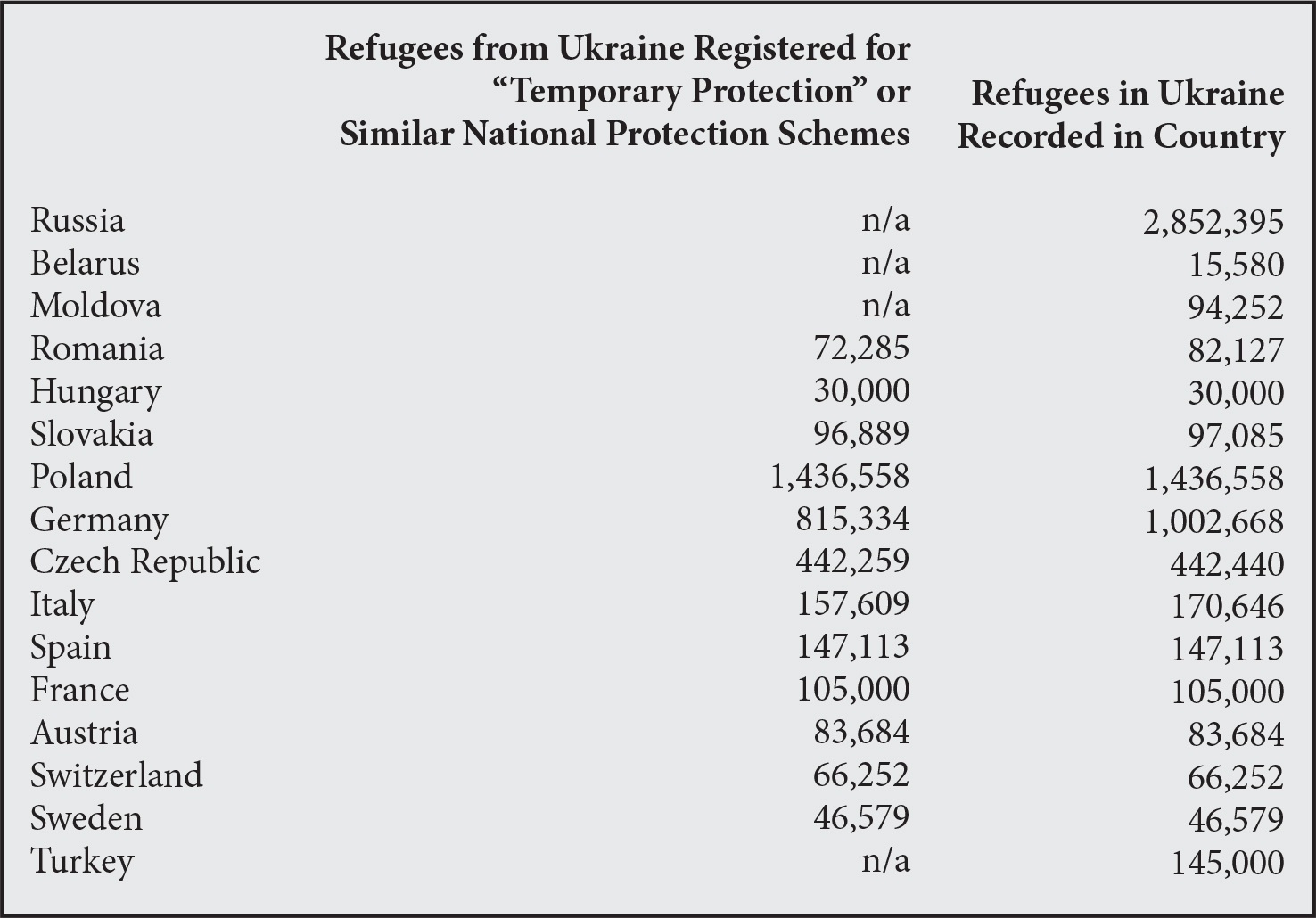

UNHCR gives us the number of those registered for “Temporary Protection” by country versus the overall number of refugees recorded in that country.31

|

Cash Assistance

On a parallel front, UNHCR has been providing cash assistance to refugees from Ukraine in various European countries, including Poland, Moldova, Romania, and Slovakia.32 This cash assistance program “is designed to act as a transitional safety net to address immediate needs until refugees can be included in national social welfare programs.” It is easy to use; upon enrollment, individuals can start retrieving cash through existing banking systems. Cash amounts vary by country. Ukrainians who sought refuge in Poland, for instance, are given the equivalent of $170 USD per person on a monthly basis or $605 per household for a minimum of three months.

Worthy of note here: The United States is UNHCR’s top government donor: $1.9 billion in 2021.33

Who Are They? Profiles and Intentions of Refugees from Ukraine

UNHCR released a report describing the profiles and intentions of refugees from Ukraine.34 Between mid-May and mid-June 2022, the refugee agency and its partners in host countries neighboring Ukraine conducted 4,900 interviews with refugees from Ukraine in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia, complemented by several focus group discussions.

Some useful information about these respondents:

- 99 percent of the respondents were Ukrainian nationals.

- 86 percent were females.

- 49 percent of the females were between 35-59 years old.

- 12 percent of the females were above 60 and 26 percent belonged to the 18-34 age group.

Respondents’ top employment sectors:

- 12 percent in Education.

- 12 percent in Wholesale and retail.

- 6 percent in Healthcare.

- 4 percent in Hotel and restaurant.

Here are several of the UNHCR report’s key findings:

- 90 percent are women and children.

- 23 percent of households had at least one person with specific needs (such as persons with serious medical conditions, persons living with disabilities, or older persons with specific protection risks).

- 77 percent of respondents have completed vocational or university studies; most have a professional /occupational background in services-related sectors.

- 73 percent were employed before leaving Ukraine.

- 82 percent had to separate from at least one immediate family member.

- 76 percent have a biometric passport.

Most of those who said they were planning on returning to Ukraine in the near future (16 percent of respondents) were only going to “stay temporarily to visit family, get supplies or help other relatives to evacuate”.

Some participants “highlighted cases of persons who returned to Ukraine because they had run out of savings and were unable to find financial security.”

Among those planning to move to another host country (this relates to those who left Ukraine more recently), a small proportion was planning to move to nearby countries (of which, 6 percent to the Czech Republic) but the large majority (75 percent) was planning to move to more distant European countries (Germany being the most frequent reported destination, with 27 percent).

A small proportion reported planning to move to non-European countries: Canada was at the top of the list with 10 percent; only 2 percent reported wanting to move to the United States.

The respondents’ main reasons for moving to another host country were family ties (26 percent), safety (27 percent), and access to employment (23 percent). Seeking asylum accounted only for 6 percent, language for 2 percent.

U.S. Response to the Ukrainian Crisis

To respond to the needs of people in Ukraine and the millions who fled the country since February, the U.S. government committed to various aid packages. It has provided over $1.5 billion in humanitarian assistance to Ukraine and its neighboring countries that are welcoming and supporting those fleeing the Russian attack.35 On the military front, the U.S. government has committed approximately $12.9 billion in security assistance to Ukraine since the beginning of Russia’s invasion on February 24.36

In May, Congress approved $40 billion in aid for Ukraine and other countries impacted by the conflict, the sixth aid package since the crisis began.37 The difference here is “that the timeline for this aid package implies the expectation of a long war.”38 Previous aid packages were meant to last a few weeks, this one, a few months.

The bill — H.R.7691, the Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022 — provides $40.1 billion in FY 2022 emergency supplemental appropriations for activities (including economic assistance, humanitarian aid, diplomatic programs, military programs, etc.) to respond to the recent Ukrainian crisis.39 $16 billion of the package is directed toward humanitarian assistance, which includes $350 million for Migration and Refugee Assistance to provide humanitarian support for refugee outflows from Ukraine.

Admissions of Ukrainians into the United States

With regards to these outflows, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken underlined early on the importance of proximity help versus resettlement efforts of Ukrainian refugees into the United States: The refugee referral process to be resettled here takes time; plus, most who fled Ukraine want to stay close to home, hoping to be able to return as soon as possible.40

Indeed, admissions under the U.S. refugee resettlement program do not happen overnight; the process (from referrals to entry into the United States) takes on average 18-24 months. Moreover, the program has been diverting its resources to various new categories of people, including illegal border-crossers and Afghans, which further slows the system.41

This explains the limited numbers of resettled Ukrainian refugees; only 918 were admitted here through the formal Refugee Resettlement Program.42

The Biden administration had to find another (and quicker) pathway to admit Ukrainians, especially after the president’s promise to welcome up to 100,000 Ukrainians, especially those with family members in the United States.43 To that end, this administration designed a fast-track admission program called “Uniting for Ukraine”, launched on April 25.44 The program is managed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and is described as “a temporary pathway that complements permanent resettlement of other Ukrainians through the USRAP [U.S. Refugee Admissions Program]”.45

This “new streamlined process” offers Ukrainian nationals (and their non-Ukrainian immediate family members) already in the EU a chance to come to the United States to join family members and/or pursue better opportunities.46 According to the Migration Policy Institute, as of 2019, some 355,000 Ukrainian immigrants were living in the United States.47

Close to 100,000 Ukrainians made it here under this program.48

Those admitted under “Uniting for Ukraine” are granted “humanitarian parole”. Parole in the immigration context is described as “official permission to enter and remain temporarily in the United States” and does not constitute a “formal admission under the U.S. immigration system”.49 Those thousands of paroled Ukrainians would ordinarily have had limited access to federal benefits, eligible only for employment authorization and Social Security. But, per the Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022, all Ukrainians (or individuals who resided in Ukraine) paroled into the United States between February 24, 2022, and September 30, 2023 (as well as their family members or caregivers after that date), will receive federal benefits, including resettlement assistance, entitlement programs, and other benefits available to refugees, even though they're not actually refugees. A couple of these benefits were recently extended from eight to 12 months.50

Uniting for Ukraine has been described as “private”, non-taxpayer-funded sponsorships.51 The reality could be quite different, as federal funds will likely be used to facilitate their admission and life in the United States.52

To be able to sponsor Ukrainians, “U.S.-based supporters” — who do not need to be U.S. citizens or even green card holders — must agree to provide them with financial support during their stay here. The U.S. sponsor must apply; Ukrainians abroad cannot directly apply for parole under this program.

That said, multiple supporters (including organizations such as resettlement agencies that are mostly funded by the U.S. government) can agree to financially support a single beneficiary to facilitate admission.53 Moreover, Ukrainian parolees are eligible for federal assistance and refugee resettlement benefits upon arrival to the United States. Parolees can use those funds to sponsor additional Ukrainian parolees, who in turn will receive the same federal benefits upon arrival, potentially creating a cycle of migration.

Should the U.S. Expect Increasing Numbers of Ukrainians?

The U.S. bet that Ukrainians will want to stay close to home, hoping to be able to return as soon as possible, might not prove to be right in the long term. True, the United States is not a preferred destination of Ukrainians who fled their country, but things can change.

As the crisis evolves into a likely stalemate, more and more will want to migrate onward looking for better opportunities or to join family members scattered further around the world (including in non-European countries).

Europe’s integration capacities, including job markets, education, housing, etc., could reach their limits soon with the ongoing flows of Ukrainians who are choosing to settle there. These capacities could be further challenged with upcoming flows as the conflict stretches in time and space. Men could be tempted to leave Ukraine at some point to join their wives and children. If that were to happen, the number of Ukrainians in need of protection would significantly increase.

With time, Ukrainians could be finding non-European countries, including the United States, more attractive. We know that diasporas attract onward migration. With the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians on U.S soil (old and new arrivals), more and more Ukrainians will want join them.

Moreover, the economic situation in the United States is likely to remain much stronger compared to Europe. Europe is experiencing a serious setback to its strong yet incomplete recovery from the pandemic because of the war in Ukraine.54 It is facing a broad array of challenges, including welcoming and integrating millions of Ukrainians and dealing with rising energy prices while trying to phase out its dependency on Russian sources of energy.

The United States admitted some 100,000 Ukrainians in just a few months. The Biden administration designed a relatively easy and speedy pathway for Ukrainians to come here and provided them with a large array of benefits to help them integrate. Those already here (recent or old arrivals) can in turn sponsor additional Ukrainians. The 100,000 newcomers add onto the existing immigrant community of 350,000 Ukrainians already here.

Those struggling in Europe might very well use this pathway and join the growing diaspora who led the way. And if, at one point, men do leave Ukraine, family reunions in the United States are to be expected. The United States needs to be ready for such permanent guests.

Seven million Ukrainians have sought refuge across Europe since the beginning of the crisis, mostly women and children since men aged 18-60 are not allowed to leave the country. Four million registered for “Temporary Protection” in the EU, while very few applied for asylum there. For a significant proportion of Ukrainians, that temporary status is likely to be permanent.

The widely touted idea that all Ukrainians want to return home is not supported by data. Most refugees come from eastern areas of Ukraine now controlled by Russia. Plus, research on re-migration patterns shows that women and children have a relatively low probability of returning, especially as the conflict stretches in time and children are well integrated in schools. Not to mention that, even prior to the February 24 invasion, one in four of the adult population in Ukraine wished to migrate. The likely future scenario involves limited possibilities for large-scale return and possible new refugee flows (including those of men who, with time, could decide to join their spouses). Family reunions could take place out of Ukraine rather than in the other direction.

Europe is experiencing a serious setback to its strong yet incomplete recovery from the pandemic because of the war in Ukraine. Faced with a broad array of challenges, including welcoming millions of Ukrainians and dealing with rising energy prices, its integration capacity could be reaching its limits. With time, Ukrainians could be finding non-European countries, including the United States, more attractive.

The United States’ bet that Ukrainians will want to stay close to home, hoping to be able to return as soon as possible, might not prove to be right in the long term. As the crisis evolves into a likely stalemate, more and more will want to move onward, looking for better opportunities or to join family members scattered around the world, including the United States.

The Biden administration designed a relatively easy and speedy pathway for Ukrainians to come here and provided them with a wide array of benefits to help them integrate. Some 100,000 Ukrainians were admitted under this new program, called “Uniting for Ukraine”, in just a few months, adding to the 350,000-strong Ukrainian immigrant community already in the United States. As the diaspora attracts onward migration, those struggling in Europe might very well use this pathway and join the earlier arrivals who led the way. And if, at one point, men do leave Ukraine, family reunions in the United States are to be expected.

End Notes

1 “Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation”, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as of October 11, 2022.

2 Ibid.

3 Noé Bauduin, “Guerre en Ukraine : quelle est la situation des réfugiés ukrainiens, six mois après le début du conflit ?”, Franceinfo news, August 24, 2022.

4 Monika Sie Dhian Ho, Bob Deen, and Niels Drost, “Long-term protection in Europe needed for millions of Ukrainian refugees”, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, September 2022.

5 “Admission of ethnic German resettlers under the Federal Expellees Act”, Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community, undated.

6 Mikael Elinder, Oscar Erixson, and Olle Hammer, “How large will the Ukrainian refugee flow be, and which EU countries will they seek refuge in?”, Delmi Policy Brief, 2022: 3.

7 “Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation”, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), October 11, 2022.

8 “Returns Increase in Ukraine, but 6.2 Million People Remain Internally Displaced”, International Organization for Migration (IOM), June 28, 2022.

9 “Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation”, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as of October 11, 2022.

10 “Ukraine Refugee Situation - Data Explanatory Note”, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), June 15, 2022.

11 Ibid.

12 Noé Bauduin, “Guerre en Ukraine : quelle est la situation des réfugiés ukrainiens, six mois après le début du conflit ?”, Franceinfo news, August 24, 2022.

13 Monika Sie Dhian Ho, Bob Deen, and Niels Drost, “Long-term protection in Europe needed for millions of Ukrainian refugees”, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, September 2022.

14 Ibid.

15 Laris Karklis and Erin Cunningham, “Three maps that explain Russia’s annexations and losses in Ukraine”, The Washington Post, September 30, 2022.

16 Ibid.

17 Asha C. Gilbert, “Reports: Ukraine bans all male citizens ages 18 to 60 from leaving the country”, USA Today, February 25, 2022.

18 Monika Sie Dhian Ho, Bob Deen, and Niels Drost, “Long-term protection in Europe needed for millions of Ukrainian refugees”, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, September 2022.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Mikael Elinder, Oscar Erixson, and Olle Hammer, “How large will the Ukrainian refugee flow be, and which EU countries will they seek refuge in?”, Delmi Policy Brief, 2022: 3.

23 Monika Sie Dhian Ho, Bob Deen, and Niels Drost, “Long-term protection in Europe needed for millions of Ukrainian refugees”, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, September 2022.

24 Ibid.

25 “Europe’s Ukrainian refugee crisis: What we know so far”, International Center for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), February 28, 2022.

26 “Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/382”, Official Journal of the European Union, March 4, 2022.

27 Vincenzo Genovese, “Brussels extends Ukrainian refugee rights to live and work in EU until 2024”, Euronews, updated October 10, 2022.

28 Monika Sie Dhian Ho, Bob Deen, and Niels Drost, “Long-term protection in Europe needed for millions of Ukrainian refugees”, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, September 2022.

29 “Latest Asylum Trends”, European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), June 2022.

30 “Analysis on Asylum and Temporary Protection in the EU+ in the Context of the Ukraine Crisis”, European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), September 7, 2022.

31 “Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation”, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), last updated August 23, 2022.

32 “How cash assistance is helping refugees from Ukraine”, The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), April 22, 2022.

33 “United States of America”, The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) website, undated.

34 “Lives on Hold: Profiles and Intentions of Refugees from Ukraine”, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), July 2022.

35 “USAID humanitarian assistance provided to the people of Ukraine surpasses $1 billion since Russia’s invasion”, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) press release, July 27, 2022.

36 “Fact Sheet on U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine”, U.S. Department of Defense fact sheet, August 24, 2022.

37 “H.R.7691 - Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022”, Congress.gov, May 19, 2022.

38 Mark F. Cancian, “What Does $40 Billion in Aid to Ukraine Buy?”, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), May 23, 2022.

39 “H.R.7691 - Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022”, Congress.gov, May 19, 2022.

40 “Secretary Blinken's Press Availability”, U.S. Department of State press release, March 4, 2022.

41 Nayla Rush, “The Refugee Resettlement Program Is Losing Its Reason for Being”, Center for Immigration Studies blog, September 7, 2022.

42 “Admissions and Arrivals”, Refugee Processing Center.

43 “FACT SHEET: The Biden Administration Announces New Humanitarian, Development, and Democracy Assistance to Ukraine and the Surrounding Region”, The White House Briefing Room, March 24, 2022.

44 “Uniting for Ukraine”, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website, updated August 5, 2022.

45 "Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for FY 2023", U.S. State Department, September 8, 2022.

46 “President Biden to Announce Uniting for Ukraine, a New Streamlined Process to Welcome Ukrainians Fleeing Russia's Invasion of Ukraine”, U.S. Department of Homeland Security press release, April 21, 2022.

47 Joshua Rodriguez and Jeanne Batalova, “Ukrainian Immigrants in the United States”, Migration Information Source (MPI), June 22, 2022.

48 Editorial Board, “The U.S. has admitted 100,000 Ukrainian migrants. It must keep going”, The Washington Post, July 30, 2022.

49 “Immigration Parole”, Congressional Research Service report, October 15, 2020.

50 Nayla Rush, “Extending ORR Benefits and Beneficiaries”, Center for Immigration Studies blog, April 25, 2022.

51 Nayla Rush, “Uniting for Ukraine: A New ‘Privately’ Sponsored Pathway to the United States”, Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, June 15, 2022.

52 Nayla Rush, “Who’s Really Paying for Ukrainians to Come to the United States?”, The National Interest, July 21, 2022.

53 Nayla Rush, “Resettlement Agencies Decide Where Refugees Are Initially Placed in the United States: Not refugees (or state and local officials)”, Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, July 16, 2020.

54 Alfred Kammer, “War In Ukraine Is Serious Setback To Europe’s Economic Recovery”, International Monetary Fund (IMF) blog, April 22, 2022.