Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

Nayla Rush is a senior researcher at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Summary: The U.S. refugee resettlement program for Syrians relies heavily on the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The UNHCR's role goes beyond providing shelter and services to people in the region; the United States entrusts UNHCR with the entire selection and pre-screening process for Syrian refugees eligible for resettlement in the United States. Given that role, more inquiry into UNHCR's activities is warranted.

Following the Paris terrorist attacks, Americans are becoming more and more apprehensive about welcoming Syrian refugees into the country, especially since the risk of ISIS infiltrating refugee groups has materialized (two of the Paris terrorists entered Europe through the island of Lesbos in Greece as refugees). According to a recent Rasmussen poll, "Most Americans say 'No' to Syrian refugees in their state": 60 percent oppose it, 28 percent are in favor, and 11 percent remain undecided.1 A bill2 calling for a tighter screening system for Syrian refugees has already passed the house and more than half of the nation's governors3 (31 to date) have now voiced their opposition to the resettlement of Syrian refugees into their states. More recently, 74 House members signed a letter "calling for House leadership to include language that would halt the Obama administration's refugee resettlement program in the ... omnibus spending bill."4 (The House leadership did not do so.)

The Obama administration and its supporters dismissed these concerns as contrary to American values ("Slamming the door in the face of refugees would betray our deepest values. That's not who we are.")5 and totally unfounded ("Obama says Syrian refugees are no bigger threat to U.S. than 'tourists'").6

At hearing7 after hearing,8 government officials have reiterated the following: The U.S. refugee resettlement program poses no threat to the safety of the American people, and all refugees — including Syrians — are subjected to rigorous screening before they are admitted into the United States. For example, Anne Richard, Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, reassured us that: "Applicants to the U.S. refugee admissions program are currently subject to the highest level of security checks of any category of traveler to the United States."9 Center for Immigration Studies Executive Director Mark Krikorian testified that "there is no reason to doubt this. The people in the Departments of State and Homeland Security, and at the intelligence agencies they work with, are doing their best to protect our people from harm. ... The problem is that proper screening of people from Syria cannot be done. We are giving our people an assignment that they cannot accomplish successfully."10

What is not common knowledge is that we are also giving another group of people a delicate assignment to accomplish within the refugee resettlement program. Whether this is being accomplished successfully is open to question.

The United States is entrusting the staff of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) with the entire selection and pre-screening process of Syrian refugees eligible for resettlement in the United States. "UNHCR is the United States' largest partner overseas. We provide substantial funding to that agency," said Larry Bartlett from the State Department.11 The United States has donated $4.5 billion to UNHCR since the beginning of the Syrian crisis in 2011. For those who question its humanitarian outreach, the United States is the most generous donor to the refugee cause of any nation in the world.

The U.S. government not only provides funds to UNHCR and relies on its staff to properly assist Syrian refugees in the region (through cash grants, shelter, access to health and education, etc.), it is depending on them for refugee status determinations and resettlement referrals.

A refugee is "someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion."12 Resettlement is the "transfer of refugees from the country in which they have sought asylum to another state that has agreed to admit them as refugees and to grant them permanent settlement and the opportunity for eventual citizenship."13 A small number of countries participate in UNHCR's resettlement program; the world's top resettlement country is the United States.

The Syrian crisis, now in its fifth year, has resulted in the "biggest refugee population from a single conflict in a generation", according to António Guterres, who ended more than 10 years as head of UNHCR on December 31. More than four million people have fled from Syria to neighboring countries in the Middle East since the beginning of the conflict in March 2011. Most, if not all, have been registered as refugees.14

As of December 31, 2015, there were 4,390,439 registered Syrian refugees in the region:15

- 2,291,900 in Turkey

- 1,070,189 in Lebanon

- 633,466 in Jordan

- 244,527 in Iraq

- 123,585 in Egypt

- 26,722 in other North African countries

Out of the four million-plus registered Syrian refugees in the region, UNHCR has so far submitted 22,427 cases to the United States for resettlement consideration. Of those, about 2,000 were accepted last year. The United States is welcoming Syrian refugees only from the 22,427 who made it through UNHCR referrals; it is not considering the remaining 4,368,012.

Of course, no Syrian has a right to be resettled here, "and there is no obligation on states to accept refugees through resettlement. ... Whether individual refugees will ultimately be resettled depends on the admission criteria of the resettlement state."16 The point here is that UNHCR presents the United States with potential resettlement cases.

What Is UNHCR and How Does It Operate?

UNHCR is the UN refugee agency, established on December 14, 1950, by the United Nations General Assembly.17 It is "mandated to lead and co-ordinate international action to protect refugees and resolve refugee problems worldwide. Its primary purpose is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees." It has the international mandate to determine who is (and who is not) attributed refugee status, to provide refugee assistance, and to decide who is eligible for resettlement in third countries.

UNHCR's ultimate goal is to seek and provide durable solutions that will allow refugees to "rebuild their lives in dignity and peace."18 There are three durable solutions available to refugees:

- Voluntary repatriation, in which refugees return safely to their country of origin;

- Local integration, in which refugees legally, economically, and socially integrate in the host country; and

- Resettlement to a third country in situations where it is "impossible for a person to go back home or remain in the host country."

UNHCR lists two preconditions for resettlement consideration: First, the applicant should be determined by UNHCR to be a refugee. Second, resettlement should be identified as the most appropriate solution after all durable solutions are assessed.

UNHCR staff present in neighboring countries in the Middle East receive Syrians who have fled their country and register them (or not) as refugees. It would not be surprising, in light of the large numbers and an evident sense of urgency, if these Syrian nationals benefited from a "group determination" of refugee status.

The process of "group determination" is explained in UNHCR's procedures handbook:19

While refugee status must normally be determined on an individual basis, situations have also arisen in which entire groups have been displaced under circumstances indicating that members of the group could be considered individually as refugees. In such situations the need to provide assistance is often extremely urgent and it may not be possible for purely practical reasons to carry out an individual determination of refugee status for each member of the group. Recourse has therefore been had to so-called "group determination" of refugee status, whereby each member of the group is regarded prima facie (i.e. in the absence of evidence to the contrary) as a refugee.

Let us assume, however, that regular procedures were followed. One interview usually is sufficient for the determination of refugee status. In case of apparent inconsistencies and contradictions, the examiner might schedule a second one to clarify any misrepresentation or concealment of facts. That said, as UNHCR explains: "often an applicant may not be able to support his statements by documentary or other proof, and cases in which an applicant can provide evidence of all his statements will be the exception rather than the rule."20 Therefore, "the requirement of evidence should not be too strictly applied." Furthermore, "untrue statements by themselves are not a reason for refusal of refugee status and it is the examiner's responsibility to evaluate such statements in the light of all the circumstances of the case."

If proofs are not required for the recognition of a refugee claim, one input is essential and that is "information on practices in the country of origin".21 "Practices in the country of origin", Syria here, are probably familiar to all Syrian nationals (not just the trained UNHCR officer in charge of interviewing refugees). Is it safe to assume that a Syrian "fighter" who was granted refugee status and was looking to resettle somewhere in the West would pass this "knowledge" test? We need to learn more about this supposedly intensive vetting process that lasts, we are told, 18-24 months (due to waiting time, not extra vetting procedures).

It is clear that refugee status attribution does not rely on material facts, but on UNHCR's general assessment of the situation. Of the four million-plus Syrians who fled to neighboring countries, 4,390,439 (probably all) were granted refugee status.

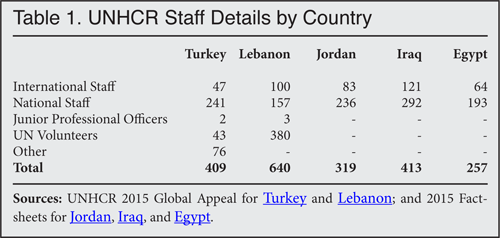

UNHCR employs some 9,000 staff in 123 countries, mostly working in field locations close to where displaced people are. In the countries hosting most of the Syrian refugees — Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt — UNHCR staff totals 2,038. Country staff details are shown in Table 1.

What do we know about UNHCR's employees in the region, the men and women the U.S. government believes possess the exceptional good judgment and expertise needed to make refugee determinations and resettlement referrals? Not much.

We know that these 2,038 staff members (of whom only 415 are international, the rest being citizens of the countries where they are working) are responsible for the registration of over four million people in distress. This entails interviewing people, checking and recording available documents, and providing refugee status. They are also in charge of follow-up assistance with housing, food, education, clothing, and the like, as well as coordination with government officials and local communities. Furthermore, they select refugees for resettlement consideration.

With 2,038 staff members for 4,390,439 refugees, that equals approximately 2,154 refugees per staff member — provided that all 2,038 staff members hold positions of responsibility within the refugee determination and resettlement process. (UNHCR staff also includes drivers, supply and finance officers, translators, and others.) If we were to only discount those listed as others, JPOs, and UN volunteers, we'd end up with 1,534 staff for 4,390,439 refugees. That's one staff member for 2,862 refugees. Even if various humanitarian partners and NGOs assist the UN agency on the ground, UNHCR staff remains in charge of the screening and referral of refugees.

Let us not forget, also, that the Middle East is a region where turmoil is not uncommon — the Syrian crisis only made it worse. Many of these hosting countries are themselves beset by political instability and civil unrest, economic hardships, and sectarian tensions and Islamic extremism (not to mention human rights and corruption issues). Numerous communities, especially the youth, suffer from extreme poverty, rising unemployment, and desperation.

For example, the average corruption score in 2014 for the five countries sheltering most of the Syrian refugees was 34.8/100 (the lower the number the more corrupt).22 The average ranking was 103.8/175 (175 being the most corrupt country in the world). For comparison, the United States scored 74/100 and ranked 17/175.

We do not doubt that UNHCR staff are receiving the best training possible in order to undertake difficult assignments in such troubled settings. We trust as well that they are driven by the most honorable intentions as they assist populations in despair. Yet faced with the very large recent flows of refugees, in unsettled countries where citizens are already struggling, mistakes are not impossible. By UNHCR's own admission, "Refugee status and resettlement places are valuable commodities, particularly in countries with acute poverty, where the temptation to make money by whatever means is strong. This makes the resettlement process a target for abuse." That said, the agency's dedication to its mission remains unaltered: "the possibilities for abuse are not a reason for reducing resettlement where the need for it persists."23

UNHCR also acknowledges the risks of "external resettlement fraud" and "internal resettlement fraud".

External resettlement fraud applies to "fraud perpetrated by persons other than those having a contractual relationship with UNHCR", such as the refugees or asylum seekers themselves. One example of external resettlement fraud is identity fraud: "Identity fraud occurs when an identity is either invented, or the identity of another real person is assumed by an impostor. Supporting documents may be missing, or fraudulent documents provided. This may occur at any stage during the process, e.g. a refugee or non-refugee 'purchases' an interview slot or a departure slot and takes the place of a refugee who has been identified as in need of resettlement."24

Other types include "family composition fraud", "one of the areas where misrepresentation or fraud is most likely to be committed"; and "document fraud" or "material misrepresentation fraud", whereby "refugees deliberately exaggerate, invent, or otherwise misrepresent the nature or details of their refugee claim or resettlement needs". Another type of external fraud is "bribery of UNHCR staff or others involved in the resettlement process with money, favors, or gifts."

"Internal resettlement fraud" refers to fraud perpetrated by UNHCR staff themselves. Examples include drafting false refugee claims or false needs assessments for resettlement; facilitating preferential processing or access to the procedure; charging a fee or asking for a favor to be added to an interview list; coaching refugees prior to or during the interview; and providing false medical attestations. Resettlement procedures are free of charge. However, the fraudulent actions described above are often undertaken for a fee, a favor, or a gift and constitute corruption.

Personal relationships with the refugees can also pose problems as "they involve a relationship of unequal power and are thus easily subject to exploitation. The staff member will always be perceived as having power over the refugee, and the refugee may thus feel obliged to provide favors, including those of a sexual nature, in order to obtain certain benefits, or to avoid negative repercussions." This could be of added concern in countries where familiarity and congeniality are general cultural traits.

UNHCR has taken measures to combat fraud in order to "preserve the integrity of resettlement".25 One of the most effective measures, according to the agency, is following standardized operating procedures carefully. Others involve:

- Clearly defining roles and responsibilities for all staff;

- Ensuring that there are tracking systems that allow each step and action to be reconstructed; and

- Counselling refugees on the implications of committing or being complicit in fraud before signing the Resettlement Registration Form (RRF).

In general terms, sanctions against fraudulent refugees are applied in a "discretionary manner" and may vary "due to a range of circumstances, including individual protection needs, country conditions, individual motives, and mitigating/aggravating factors." Falsification of personal information may result in a "warning, or a time-limited suspension of resettlement processing". The dissuasive effect of these sanctions on desperate refugees remains to be proven.

Let's not forget that it is usually the most vulnerable refugees who are chosen for resettlement. UNHCR's resettlement submission categories26 include:

- Legal and/or Physical Protection Needs of the refugee in the country of refuge;

- Survivors of Torture and/or Violence;

- Medical Needs, in particular life-saving treatment that is unavailable in the country of refuge;

- Women and Girls at Risk;

- Children and Adolescents at Risk; and

- Family Reunification, when resettlement is the only means to reunite refugee family members who, owing to refugee flight or displacement, are separated by borders or entire continents.

Of the 22,427 Syrian cases referred by UNHCR to the United States for resettlement, what do we know? Which categories do they belong to? Are they victims of torture or just reuniting with family? Do they have specific medical needs? Which country of refuge do they come from? Which UNHCR office or offices referred them to the United States? Did they come forward on their own or were they encouraged by UNHCR staff to apply?

More importantly, and knowing that "a foundation of resettlement policy is that it provides a durable solution for refugees unable to voluntarily return home or remain in their country of refuge,"27 were those refugees truly unable to remain in the hosting country? Why?

All of these questions remain unanswered.

We need to learn more about this supposedly intensive vetting process that lasts, we are told, 18-24 months. Let's assume that candidates for resettlement were interviewed twice by UNHCR before their cases reach the U.S. State Department, as Larry Bartlett explained: "So by the time our folks are reviewing the application, they've already been talked to twice. They have had a very good incentive to provide accurate information to the UNHCR because that's how — at that registration that's how they get food rations and housing, for the most part." 28

We do not doubt that incentive was key, especially if the United States is invoked as a possible destination. But no matter how often these people are interviewed by UNHCR (twice or more), the same guidelines apply: "The mere absence of information, or one's inability to find information that supports an applicant's claim, should not in itself justify a negative eligibility decision."29 What is (only) required from applicants are statements that "must be coherent and plausible, and must not run counter to generally known facts."30

In the end, UNHCR's policy is based on the assumption that "It is hardly possible for a refugee to 'prove' every part of his case and, indeed, if this were a requirement the majority of refugees would not be recognized. It is therefore frequently necessary to give the applicant the benefit of the doubt."31

That is understandable since, let us not forget, UNHCR's humanitarian mission is first and foremost to help refugees. The words of a nun who ran a center that assisted migrant housemaids in the Middle East resonate here; when asked whether she had doubts about the stories women told her when they came to her for help, she replied, "Of course, but at the Centre, we choose to believe every story." That is what nuns do. And that is what Jesus would have probably done, to answer a journalist's sensational headline.32

In humanitarian settings, when evidence cannot be relied upon, one is left with a subjective appraisal of the honesty of persons in need of help. The only choice could be, in the end, to choose to trust the applicant. Except that United States government officials are not in charge of a Christian center, nor are they heading a humanitarian agency. They cannot simply follow their hearts, nor can they run this country on a benefit-of-the-doubt policy. And trusting UN staff to do a perfect job should not be a blind option.

UNHCR's screening and referral processes are worthy of scrutiny — very much in need of scrutiny, in fact.

Let us not forget that resettlement is one of UNHCR's "durable solutions". According to USCIS, resettled refugees "are required by law to apply for a green card (permanent residence) in the United States one year after being admitted as a refugee."33 They can apply for citizenship four years later (not five, as the five-year count for refugees starts on the day of arrival). From this perspective, a resettlement card gives access to a citizenship — for the resettled refugees and later their families, since family reunification is implied here.

Resettled refugees can, in fact, ask for their families to join them. In 2012, and following a four-year suspension for DNA testing fraud, the United States reinstated the Priority Three (P-3) family reunification program for spouses, unmarried children under 21, and parents of persons lawfully admitted to the United States as refugees or asylees.34 This is important because, by UNHCR's own admission, "family composition fraud" is "one of the areas where fraud is most likely to be committed."

In summary, Americans are asked today to welcome Syrian refugees without hesitation and have total faith in the refugee resettlement program. They are asked to give the benefit of the doubt to UNHCR staff in tormented countries, and to trust their own government officials with their national security — officials who are delegating parts of their screening responsibilities overseas to the UNHCR.

How about returning the favor? How about we also give Americans the benefit of the doubt? Why not believe that American men and women are genuinely concerned about their families' safety as they ask for a halt in the refugee resettlement program for Syrian refugees? Refugees need only be "believable"; can we treat Americans just as well? Stop undermining those who doubt the system by accusing them, at best, of being politically driven and, at worst, of being racist, anti-immigrant, and a shame to America.

The UNHCR is deciding not only who can move to the United States, it is also choosing who gets a chance to become American and who doesn't. Given such high stakes, Americans should be encouraged to question this opaque system.

End Notes

1 "Most Say 'No' to Syrian Refugees In Their State", Rasmussen Reports, November 19, 2015.

2 Jennifer Steinhauer and Michael D. Shear, "House Approves Tougher Refugee Screening, Defying Veto Threat", The New York Times, November 19, 2015.

3 Ashley Fantz and Ben Brumfield, "More than half the nation's governors say Syrian refugees not welcome", CNN, November 19, 2015.

4 "74 House Members Sign Letter to Stop Refugee Resettlement Program", NumbersUSA, December 15, 2015.

5 President Obama (@POTUS), Twitter post, November 18, 2015, 8:49 a.m.

6 Dave Boyer, "Obama says Syrian refugees are no bigger threat to U.S. than 'tourists'", Washington Times, November 19, 2015.

7 Hearing on "Syrian Refugees and the Refugee Resettlement Program", Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and the National Interest, October 1, 2015.

8 Testimony of Anne C. Richard at, "The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Its Impact on the Security of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program", United States House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary, November 19, 2015.

9 Ibid.

10 Testimony of Mark Krikorian at "The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Its Impact on the Security of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program", United States House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary, November 19, 2015.

11 Hearing on "Syrian Refugees and the Refugee Resettlement Program", Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and the National Interest, October 1, 2015.

12 "Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), December 2010.

13 "UNHCR Resettlement Handbook", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2011.

14 "Syria Regional Refugee Response Inter-agency Information Sharing Portal", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), last updated December 17, 2015.

15 "Syrian Arab Republic: Humanitarian Snapshot", UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, January 4, 2016.

16 "UNHCR Resettlement Handbook", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2011.

17 "About Us", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) website.

18 "Durable Solutions", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) website.

19 "Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), reedited January 1992.

20 "Handbook and Guidelines on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), December 2011.

21 Ibid.

22 "Corruption Perception Index", Transparency International website.

23 "Policy and Procedural Guidelines: Addressing Resettlement Fraud Perpetrated by Refugees", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), March 2008.

24 "UNHCR Resettlement Handbook", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2011.

25 Ibid., Chapter 4.

26 Ibid., Chapter 6.

27 "Policy and Procedural Guidelines: Addressing Resettlement Fraud Perpetrated by Refugees", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), March 2008.

28 Hearing on "Syrian Refugees and the Refugee Resettlement Program", Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and the National Interest, October 1, 2015.

29 "UNHCR Resettlement Handbook", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2011.

30 "Policy and Procedural Guidelines: Addressing Resettlement Fraud Perpetrated by Refugees", UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), March 2008.

31 Ibid.

32 Michelle Boorstein, "Would Jesus take in Syrian refugees?" , The Washington Post, November 16, 2015.

33 "Green Card for a Refugee", U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website, last updated March 30, 2011.

34 "Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2015", U.S. Department of State, September 18, 2014.