Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Todd Bensman is a senior national security fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Introduction

On June 24, 2016 — during the waning days of President Barack Obama's administration — Department of Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson sent a three-page memorandum to 10 top law enforcement chiefs responsible for border security.1 The subject line referenced a terrorism threat at the nation's land borders that had been scarcely acknowledged by the Obama administration during its previous seven years. So far, it also has evaded much mention in national debate over Trump administration immigration policy.

The subject line read: "Cross-Border Movement of Special Interest Aliens".

What followed were orders, unusual in the sense that they demanded the "immediate attention" of the nation's most senior immigration and border security leaders to counter such an obscure terrorism threat.

Secretary Johnson ordered that they form a "multi-DHS Component SIA Joint Action Group" and produce a "consolidated action plan" to take on this newly important threat. He was referring to the smuggling of migrants from Muslim-majority countries, often across the southern land border — a category of smuggled persons likely already known to memo recipients as special interest aliens, or SIAs. Secretary Johnson provided few clues for the apparent urgency, except to state: "As we all appreciate, SIAs may consist of those who are potential national security threats to our homeland. Thus, the need for continued vigilance in this particular area." Elsewhere, the secretary cited "the increased global movement of SIAs."

The unpublicized copy of the memo, obtained by CIS, outlined plan objectives. Intelligence collection and analysis, Secretary Johnson wrote, would drive efforts to "counter the threats posed by the smuggling of SIAs." Coordinated investigations would "bring down organizations involved in the smuggling of SIAs into and within the United States." Border and port of entry operations capacities would "help us identify and interdict SIAs of national security concern who attempt to enter the United States" and "evaluate our border and port of entry security posture to ensure our resources are appropriately aligned to address trends in the migration of SIAs."

Secretary Johnson saw a need to educate the general public about what was about to happen. Public affairs staffs would craft messaging that the new program would "protect the United States and our partners against this potential threat."

However, no known Public Affairs Office education about SIA immigration materialized as Secretary Johnson and most of his agency heads were swept out of office some months later by the election of Republican President Donald Trump. Whatever reputed threat about which the Obama administration wanted to inform the public near its end remains narrowly known. So, too, are whatever operations developed from the secretary's 2016 directive.

Perhaps notably, the cross-border migration of people from Muslim-majority nations, as a trending terror threat, has gone missing during contentious national debates over President Trump's border security policies and wall. Most discourse has been confined to Spanish-speaking border entrants rather than on those who speak Arabic, Pashtun, and Urdu.

So what is an SIA and why, in 2016, did this "potential national security threat" require the urgent coordinated attention of agencies, with not much word about it since? This Backgrounder provides a factual basis necessary for anyone inclined to add the prospect of terrorism border infiltration, via SIA smuggling, to the nation's ongoing discourse about securing borders.

It provides a definition of SIAs and a history of how homeland security authorities have addressed the issue since 9/11. Since SIA immigration traffic is the only kind with a distinct and recognized terrorism threat nexus, its apparent sidelining from the national debate presents a particular puzzlement.

No illegal border crosser has committed a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, to date. A Somali asylum-seeker who crossed the Mexican border to California in 2011 did allegedly commit an ISIS-inspired attack in Canada, wounding five people in 2017, and numerous SIAs with terrorism connections reportedly have been apprehended at the southern border, to include individuals said to be linked to designated terrorist organizations in Somalia, Sri Lanka, Lebanon, and Bangladesh.2 But while most SIAs likely have no terrorism connectivity, the purpose of this Backgrounder is not to assess the perceived degree of any actual terrorist infiltration threat. The purpose, rather, is to establish a less disputable basis for discourse and action by either Republicans or Democrats through a homeland security lens: That SIA smuggling networks provide the capability for terrorist travelers to reach the border, and also that legislation-driven strategy requires U.S. agencies to tend to the issue regardless.3

Perceived Terrorist Infiltration Threat at the Border: A Brief History

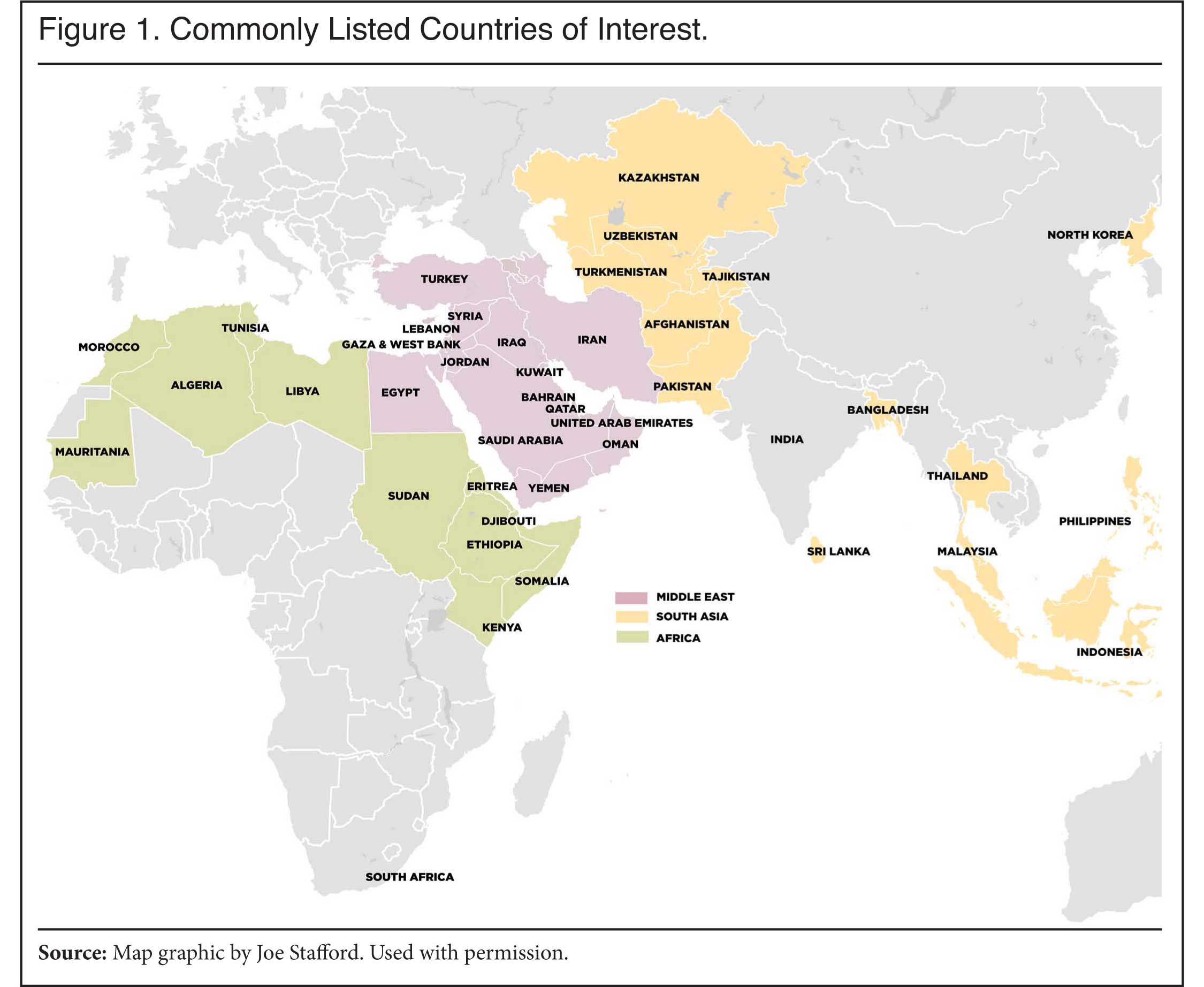

Collectively, almost all of the counterterrorism legislation enacted after the 9/11 attacks spawned a U.S. effort to reduce the threat of terrorist infiltration at the U.S. Southwest Border, by focusing on international SIA smuggling networks and the immigrants they transported. A content review of these laws shows that security agencies, in the early- to mid-2000s, were expected to look far beyond Mexican immigration toward countries of the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa.4 It was from those distant countries that long-haul smuggling railroads were transporting migrants, most often, through Latin American countries to the Southwest border.5 The new laws explicitly required agencies, such as Customs and Border Protection (CBP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the Border Patrol, to interdict Islamist terrorist travelers before they reached the border and certainly after.6

The hallmark Homeland Security Act of 2002, for instance, established the key security objective of "preventing the entry of terrorists and terrorist weapons" by threat actors it described as "transnational terrorists, transnational criminals and unauthorized migrants."7 The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 mandated "a cohesive effort to intercept terrorists, find terrorist travel facilitators, and constrain terrorist mobility, domestically and internationally."8 The act created a Human Smuggling and Trafficking Center to collect intelligence on "clandestine terrorist travel" toward the American border.9 The Secure Fence Act of 2006 states that its purpose is, in significant part, "the prevention of all unlawful entries to the U.S., including entries by terrorists."10

Strategic plans followed, reflecting congressional wishes. For example, the first of several Border Patrol strategic plans in 2005 marked an agency priority as: "establishing substantial probability of apprehending terrorists and their weapons as they attempt to enter illegally between ports of entry."11 The Border Patrol was now to protect the nation from illegal aliens who "may have ties to ... countries at higher risk of having groups that sponsor terrorism."12 A 2006 White House National Strategy to Combat Terrorism described a priority goal of "denying terrorists entry to the United States" by disrupting their travel "internationally and across and within our borders," and undermining the "illicit networks" that facilitate the travel.13

The leaders to whom these responsibilities fell acquired an objective-hitting target set: the smuggling networks and people they were already transporting — before 9/11 — from countries where terrorists operated.14 The thinking was that extremists seeking U.S. entry through the southern border would require the highly specialized smugglers who uniquely understood how to navigate the complexities of clandestine, long-haul air, land, and sea travel. One 2006 National Counterterrorism Center intelligence report characterized the thinking: "Terrorists could try to merge into SIA smuggling pipelines to enter the U.S. clandestinely. ... Al Qaeda and other groups sneak across borders in other parts of the world and may try to do so in the US, despite risks of apprehension or residing in the US without proper documentation."15

But how would a strategy be developed and executed? The short answer: Create lists of countries and then tag migrant citizens of those designated countries for enhanced security screening when they are apprehended at the U.S. border or en route. And hunt down the smugglers and dismantle the networks responsible for transporting migrants from these regions of the world.

Developing a Response: The Early Years

A new lexicon and new rules were needed to guide front-line CBP inspectors at ports of entry and the Border Patrol agents between them in identifying illegal immigrants from Muslim-majority countries, in what they should do after encountering one. What developed was a hodgepodge, changeling system by which an illegal immigrant apprehended at the border or inland might be tagged as an SIA — or some variant of the term — if they hailed from nations on a "countries of interest" list. These could then be subjected to additional national security screening and intelligence collection on smugglers for overseas investigations.

These migrants from the worrisome war-on-terror parts of the world fit under the broad DHS-CBP category well-known as "Other Than Mexican" (OTM). But the OTM category proved overly broad for front-line operations because it encompassed other nations, like China and the countries of Central and South America.

Secretary Johnson's 2016 vision of a more unified, cross-government counter-infiltration program likely came in recognition that definitions have shifted and evolved over time and among agencies. But sometime in the early 2000s, an OTM sub-category "special interest aliens" was created for CBP officers to tag migrants of higher-priority national security concern from, for instance, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. After all, countries such as these fed smuggling routes to the Southwest Border, and also the U.S. military was combating terrorist organizations perhaps motivated to use them.

The U.S. government has lacked a formal or unified definition of SIAs, although meanings for other terms that came into being seem not to differ significantly. DHS/ICE has defined a "special interest alien" as a "foreign national originating from a country identified as having possible or established links to terrorism."16 Different agencies under various administrations have used terms of similar meaning, such as "Aliens from Special Interest Countries", "Third Country Nationals", and "Aliens from Specially Designated Countries."

Nor is there a commonly agreed-upon list of countries for use in tagging illegal immigrants as SIAs so they can undergo the extra security screening, though meanings likewise seem uniform. In congressional testimony, DHS officials have interchangeably used the terms "special interest country" and "country of interest" to refer to nations known to harbor terrorists or foment terrorism.17 The State Department and elements of the intelligence community have maintained the term "Specially Designated Countries" to describe nations that show a "tendency to promote, produce or protect terrorist organizations or their members."18

The earliest known "specially designated country list" for use by CBP was created in 2003 but has fluctuated since.19 The National Counterterrorism Center and DHS Intelligence & Analysis, at least for a time after 2009, agreed on one country list of 33 (plus two territories), while other agencies kept their own lists of varying lengths ranging from 33 to as many as 52.20 The most current list is not publicly available.

One early directive to frontline officers, listing 35 countries, went out on November 1, 2004, in a memorandum from Border Patrol Chief David Aguilar to "All Sector Chief Patrol Agents".21 It listed mostly Muslim-majority countries, but also North Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand. Officers were instructed to take the following steps upon encountering anyone from those countries:

- File a "Significant Incident Report to the CBP Situation Room within one hour to flag any SIA at least 14 years old.

- Contact sector communications for records checks.

- Contact the National Targeting Center for additional records checks.

- Contact the local FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force for "follow-on" interviews.

- Copy pocket litter for possible additional intelligence.

- Complete and forward a G-392 Intelligence Report through Border Patrol intelligence channels.

- Enroll all SIAs 14 years old or older into various biometric identification systems.

In the years since Chief Aguilar's memo, the country lists have fluctuated, sometimes depending on diplomatic and political winds. In August 2011, for instance, a DHS Office of Inspector General report disclosed that Obama administration ICE officials decided the 2003 list was "outdated and is being eliminated" because it was "not based on any judgment that the states listed supported, sponsored or encouraged terrorism." The administration added that, indeed, "many of the states listed are important and committed partners of the United States in countering terrorism."22

The Hidden U.S. Strategy: Unassessed and Uncoordinated?

"There's a whole category called SIAs—special interest aliens is what it stands for. We watch that very carefully. We have been working—not just with Mexico, but countries of Central America, in terms of following more closely people transiting the airports and the like. And so, again, our efforts there are to try to ... take as much pressure off the physical land border as we can."

— DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano, remarks to a reporter in Washington, D.C., January 2012.23<.p>

Ample evidence shows that some components of the American homeland security enterprise have remained dedicated to the SIA terrorist infiltration threat issue, both on the home front and abroad. DHS Secretary Johnson's memo noted in its preamble that, "The department is doing much to identify and address 'Special Interest Aliens' apprehended at our borders." But the extent to which the effort is appropriately resourced, collaborative enough, or engaged across the enterprise is not in evidence. Nor is whether Congress has assessed or accounted for the overall SIA effort as various immigration enforcement policies and strategies regarding only Spanish-speaking immigrants are discussed and implemented. SIA traffic, as a threat issue, seems a neglected, potentially high-consequence step-child.

On the home front, the extent to which Chief Aguilar's required security screening steps have continued since 2004 is not well known. Some variation of the screening processes, though, was in evidence at least through 2009, when a GAO report noted that the intelligence agencies were still being notified when SIAs were encountered.24 Court prosecution records and isolated media reporting show that FBI and ICE agents have, in more recent years, conducted interviews with many SIAs in U.S. detention facilities and also in the custody of Mexico — though inconsistently resourced there and with imperfect effectiveness.25 Records from a 2017 prosecution against the Pakistani smuggler Sharafat Ali Khan show that agents interviewed dozens of his clients as prospective material witnesses.26

Abroad, efforts to interdict SIA smugglers are long-standing, with emphasis dating to the 9/11 attacks. ICE's Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) division occupies the tip of the U.S. spear in countering the perceived terrorist infiltration threat abroad (a circumstance that public proposals to disband ICE have not taken into account). ICE-HSI dismantles SIA smuggling networks as part of the Extraterritorial Criminal Travel Strike Force program active throughout Latin America and elsewhere.27 ICE once described this mission as involving 240 agents in some 48 foreign attaché offices and as an effort to "aggressively pursue, disrupt and dismantle foreign based criminal travel networks — particularly those involved in the movement of aliens from countries of concern."28 Other agencies and American assets apparently have been brought to bear, as well. Gustavo Barreno, who served from 1997 through 2005 as Guatemala's federal prosecutor in charge of enforcing his country's human trafficking laws, told a reporter that joint operations against SIA smuggling involved American satellites, Coast Guard cutters, and the U.S. Navy.29

The ICE-HSI investigations are complex affairs, spanning various countries in collaboration with foreign law enforcement and intelligence services. But operating in the secrecy necessary for operational security, ICE-HSI foreign operations have been vulnerable to diversion. One GAO assessment, for instance, noted that agents had spent only 17 percent of their time on counterterrorism smuggling investigations, the rest on traditional drug trafficking.30

Sizing Up the Threat Scope and Recent Urgency

An obvious question for foundational understanding is: How many SIAs actually reach the southern border at and between ports of entry? That answer is not publicly known. CBP's Office of Intelligence carefully tracks this data. But the agency conspicuously never publishes SIA apprehensions with the OTM apprehension data that it has routinely published.

Bits and pieces of the puzzle have surfaced anyway. Occasional information leaks, government reports, and Freedom of Information Act requests over time suggest that hundreds of SIAs, perhaps ranging to the low thousands (depending on changing country of interest lists), have been annually apprehended at the southern border since 9/11.31 One set of SIA apprehension data reflecting September 2001 through 2007 showed that nearly 6,000 SIAs from 42 countries had been apprehended at the border.32

Other SIA apprehension data made public since 2007 suggest the traffic has continued at a regular pace, at least in the hundreds per year in Texas alone and hundreds more in California. A 2009 GAO audit of Border Patrol inland highway checkpoints in Texas found more than 530 SIAs logged in 2008, including three "identified as linked to terrorism".33 A confidential Texas Department of Public Safety intelligence report leaked in 2015, citing CBP data, disclosed 439 encounters with SIAs in Texas during the first nine months of 2014, a 15 percent increase over the previous year.34 A joint DHS-California fusion center intelligence report showed that 430 SIAs from 20 nations were apprehended in California during FY 2007 and another 440 in FY 2008.35 The same document reported 729 from 24 countries across the Southwest Border in FY 2007 and 944 in FY 2008. Media reporting, usually leaving unaddressed homeland security implications, shows that Syrians and Iraqis have been reaching the southern border for years with the aid of smugglers.36 The capacity for terrorists to reach the U.S. southern border has been hiding in plain sight. But still, the threat and response to it likely remain unevaluated as a whole, perhaps due to its existence outside the main lanes of public consciousness and comprehension.

Routes of Travel

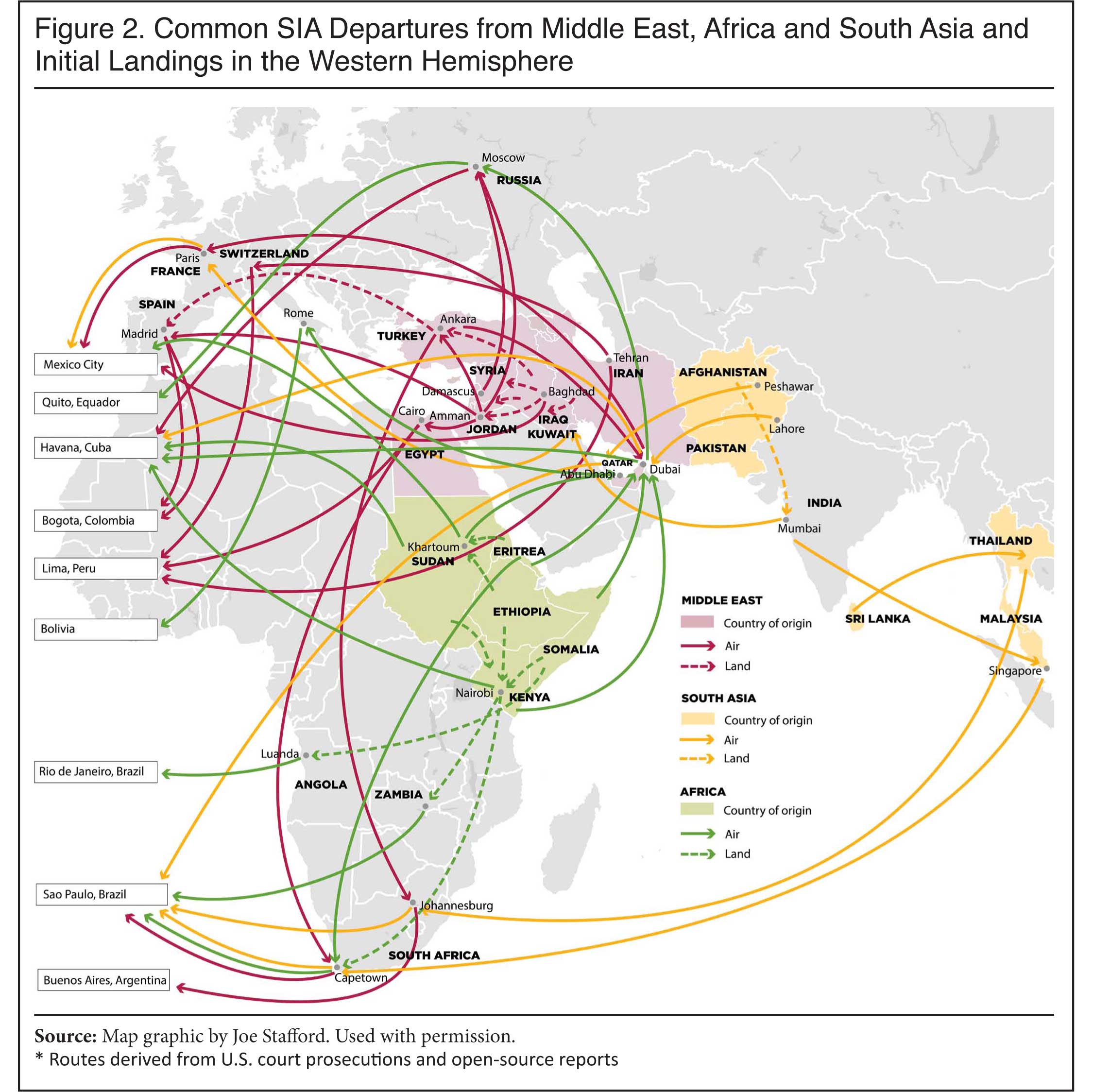

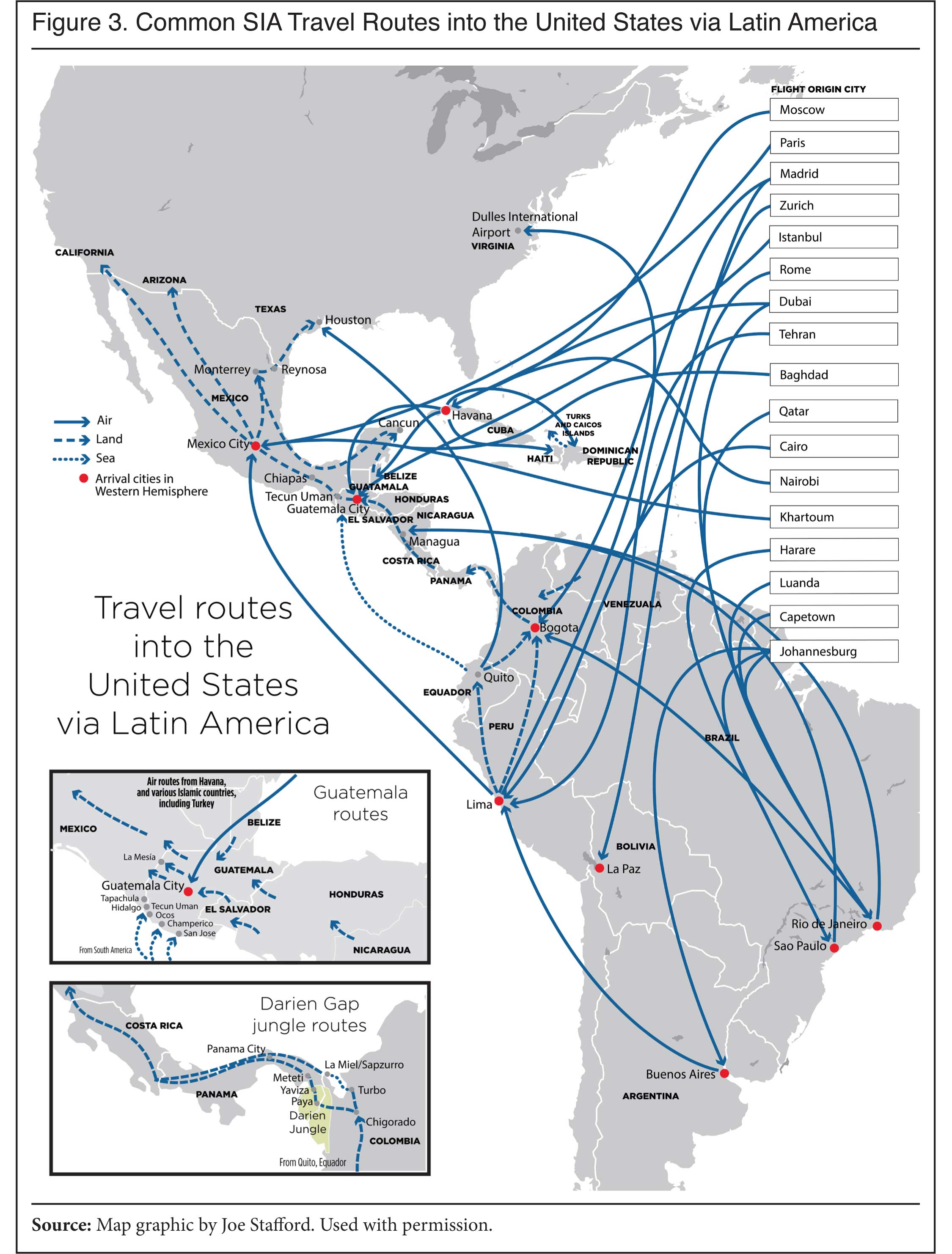

Recent research about SIA travel, based on court records from more than 20 SIA prosecutions, shows a number of typical routes, all of which invariably landed migrants in South America, Central America, or Mexico to stage treks to the U.S. southern border.37 They are as follows:

- The Middle East. Routes most often ran from origin nations through Turkey and Greece to European countries — sometimes first through the Gulf States of United Arab Emirates and Qatar. Migrants originating from Middle Eastern countries most often landed for initial staging in Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, and Mexico.

- North and East Africa. Routes often ran from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan through the Gulf States and occasionally Europe but mostly through South Africa, Kenya, and Sudan. Common landing zones in Latin America for Africans were Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Cuba, and Mexico City.

- South Asia. Routes most often ran through India, Singapore, and the Gulf states. South African international airports figured as frequent transit points.

Conclusion

Former Secretary Johnson's 2016 directive for a more integrated, whole-of-government approach to the SIA terrorism threat at the Southwest Border, relative to whatever efforts were already underway, did not occur in a vacuum. At the time, he and other national security leaders would have been aware that in 2015-2016 (and through 2017 to present), attacks by ISIS terrorist operatives, sympathizers, and returning fighters were afflicting European allies.38 Many of these plots and attacks, particularly those involving high casualties in Paris and Brussels, were conducted by operatives who were smuggled camouflaged among millions of illegal immigrant asylum seekers.39 These attackers and plotters — some highly wanted European citizens who'd been fighting with ISIS and needed to pose as Syrian asylum seekers to cover identities, as well as others indigenous to their own distant countries — were smuggled long distances to the continent's external borders.40 In April 2018, for instance, a senior ISIS leader reportedly was apprehended in Turkey with three other operatives posing as Syrian war refugees preparing to be transported by human smugglers to Europe.41 Most of these attackers would have been identified as SIAs, in the American context, because they had traveled from "countries of interest".

If foreign-based terrorists observed success in this use of migration travel tactics to reach European targets, perhaps they and U.S. homeland security leaders like Secretary Johnson discerned a similar prospect they could reach the U.S.-Mexico border in the same manner. Records from court prosecutions of SIA smugglers show the use of fraudulent documents, human smugglers, and illegal border crossings to Europe's external border is also common among SIAs who travel from those same countries to the U.S.-Mexico border.42 So it is reasonable to speculate that terrorists who fought with ISIS in Syria (and still do in a dozen nations hosting ISIS franchises) began eyeing smuggling routes to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Obvious differences do exist between smuggling to Europe and to the U.S. border. Distances to the U.S. border are greater and the costs therefore higher. Those two factors would surely result in far fewer than the camouflaging millions who marched toward Europe starting in 2015.

From what is publicly known of the American SIA-countering effort, disharmony and disunity are indicated, at the least by varying definitions and country lists as discussed here. Recently, researchers for the Small Wars Journal, among the few who are in the know about SIAs, have criticized the apparent lack of a more dedicated whole-of-government approach to countering the terror threat inherent in this kind of immigration. They recently observed that an absence of a unified, dedicated, and resourced approach, maybe like what Secretary Johnson ordered, represents a "strategic and operational level failure ... a consequence of not having the requisite strategic leadership and policy guidance."43

In the ongoing public debates about immigration enforcement, the absence of SIAs as even a consideration raises the prospect of high-consequence negligence.

End Notes

1 Jeh Johnson, "Cross Border Movement of Special Interest Aliens", Department of Homeland Security memorandum, June 24, 2016.

2 See, for example: "Man charged in Edmonton attacks crossed into U.S. from Mexico, records show", CBC News, 4 October 2017; "Border Surge Report", Texas Department of Public Safety report prepared for Gov. Greg Abbott, posted in the body of: Brian M. Rosenthal, "Border surge harming crime fighting in other parts of Texas, internal report finds", Houston Chronicle, February 24, 2015; Reid Wilson, "Texas officials warn of immigrants with terrorist ties crossing southern border", The Washington Post, February 2015, citing leaked law enforcement sensitive materials; Pauline Arrillaga and Olga R. Rodriguez, "The terror-immigration connection", Associated Press, July 3, 2005; Warren Richey, "Are terrorists crossing the US-Mexico border? Excerpts from the case file", Christian Science Monitor, January 15, 2017.

3 This Backgrounder focuses on the Southwest border because, to date, it has attracted far more spending and human resource allocations, based on human traffic volumes, than has the northern border. The resources allocated to the southern border are in line with perceptions — often empirically supported — that access to Canada is primarily geographically limited to controlled air and sea ports, as well as the absence of all but one contiguous neighboring country, the United States. That geographical circumstance, as well as improved immigration security protocols enacted with the United States after 9/11, limits the number of uninvited, non-vetted migrants entering Canada, whereas the U.S. southern border allows access (through Mexcio) to nearly two dozen Latin American nations accessible from other continents. The porosity of the Canadian-U.S. border, however, is likely vulnerable to Canada-based extremists who are citizens or have other legal status.

4 In 2007, as a journalist, the author interviewed federal law enforcement officials who said that, prior to 9/11, law enforcement mainly targeted sex trafficking networks moving women and children through Guatemala. After 9/11, however, U.S. assets in the region switched to target smugglers of people from Muslim-majority countries. See Todd Bensman, "Breaching America: The Latin Connection", San Antonio Express-News, May 21, 2007.

5 Court records from prosecutions reflecting pre-9/11 smuggling of people from the Middle East are in evidence. For example, the Iranian-American smuggler Mehrzad Arbane ran a profitable operation for years prior to 9/11 in which he transported Iranians, Syrians, Iraqis, and Jordanians into the United States. Court records show he switched to cocaine trafficking after 9/11 because, as he told an associate, he feared he "may have smuggled two of the hijackers who flew the planes into the towers in New York on September 11, 2001." See United States v. Mehrzad Arbane, 11th Cir. Ct. (S.D. Fla., 2003), Case complaint; Scott Wheeler, "Drug Smuggler Claims He May Have Snuck 9/11 Hijackers into the U.S.", CSN News, May 24, 2004.

6 "Border Patrol Checkpoints Contribute to Border Patrol's Mission, but More Consistent Data Collection and Performance Measurement Could Improve Effectiveness", United States Government Accountability Office Report 09-824, August 2009.

7 Homeland Security Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107–296, Title IV, Subtitle A, Sec. 401.

8 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, Pub. L. 108–458, Sec. 7201, b1.

9 "Establishment of the Human Smuggling and Trafficking Center: A Report to Congress", Human Smuggling and Trafficking Center, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, June 16 2005.

10 Secure Fence Act of 2006, H.R. Rep. No. 6061, Sec. 2(b).

11 "National Border Patrol Strategy", Office of Border Patrol, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, September 2004. See Executive Summary.

12 "Border Patrol: Checkpoints Contribute to Border Patrol's Mission, but More Consistent Data Collection and Performance Measurement Could Improve Effectiveness", United States Government Accountability Office Report 09-824, pp. 1 and 14, August 2009.

13 "National Strategy for Combating Terrorism", The White House, September 2006.

14 Blas Nuñez-Neto, Alison Siskin, Stephen Viña "Border Security: Apprehensions of 'Other Than Mexican' Aliens", Congressional Research Service Report RL33097, September 22, 2005.

15 "Update: 2006 SIA Trends Reveal Vulnerabilities Along Route to US.", National Counterterrorism Center Report NSAR 2007-21. The author obtained this report while working as a journalist in 2007.

16 "Special Interest Alien Use of the California-Mexico Border", Department of Homeland Security joint assessment with the California State Terrorism Threat Assessment Center, August 2009. This document was obtained while the author was working as a journalist in Texas.

17 See Blas Nuñez-Neto, Alison Siskin, Stephen Viña "Border Security: Apprehensions of 'Other Than Mexican' Aliens", Congressional Research Service Report RL33097, September 22, 2005; and testimony of USBP Chief David Aguilar before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Immigration, Border Security, and Citizenship, April 28, 2005. Said Aquilar, "Special Interest Countries ... are basically countries designated by our intelligence community as countries that could export individuals that could bring harm to our country in the way of terrorism."

18 "Supervision of Aliens Commensurate with Risk", Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General Report 11-81, December 2011, p. 5.

19 "Supervision of Aliens Commensurate with Risk", Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General Report 11-81, December 2011, p. 18.

20 Department of Homeland Security joint assessment with the California State Terrorism Threat Assessment Center, "Special Interest Alien Use of the California-Mexico Border", August 2009. This document was obtained while the author was working as a journalist in Texas. The NCTC intelligence report "2006 SIA Trends Reveal Vulnerabilities Along Route to US", obtained by the author while working as a journalist, listed the countries as follows: Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, the Philippines, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, the United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, and Yemen, as well as the territories of Gaza and the West Bank. DHS/ICE also recognized Thailand as an SIA country. In 2003, the American Immigration Lawyers Association obtained and published on its website (no longer available) a "countries of interest" list that included 52 countries. They were Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Bahrain, Bhutan, Brazil, Congo, Cyprus, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Liberia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Philippines, Qatar, Republic of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, and Venezuela.

21 David V. Aguilar, "Arrests of Aliens from Special Interest Countries", U.S. Customs and Border Protection memorandum, November 1, 2004.

22 "Supervision of Aliens Commensurate with Risk", Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General Report 11-81, December 2011, p. 18.

23 Penny Star, "Napolitano: DHS Is Working with Mexico on 'Special Interest Aliens' Threat along the U.S.-Mexico Border", CNS News, January 17, 2012.

24 "Border Patrol: Checkpoints Contribute to Border Patrol's Mission, but More Consistent Data Collection and Performance Measurement Could Improve Effectiveness", United States Government Accountability Office Report 09-824, pp. 1 and 14, August 2009.

25 "Breaching America: War Refugees or Terror Threat?" , San Antonio Express News, May 20-24, 2007.

26 United States v. Sharafat Ali Khan, Case 1:16-cr-00096-RBW, Document 1, Criminal Complaint, filed June 7, 2016.

27 See "Foreign National Sentenced to 31 Months in Prison for Leadership Role in Human Smuggling Conspiracy", Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs press release, October 17, 2017; and "Jordanian National Arrested in New York to Face Charges for a Conspiracy to Bring Aliens Into the United States", Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs press release, July 30, 2018.

28 Testimony of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Homeland Security Investigations Executive Associate Director James Dinkins to the House Homeland Security Committee Subcommittee on Border, Maritime, and Global Counterterrorism hearing titled "Enhancing DHS's Efforts to Disrupt Alien Smuggling Across Our Borders," July 22, 2010.

29 "Breaching America: The Latin Connection", San Antonio Express News, May 20-24, 2007.

30 Richard M. Stana, "Alien Smuggling: DHS could Better Address Alien Smuggling along the Southwest Border by Leveraging Investigative Resources and Measuring Program Performance", GAO Report 10-919T, July 22, 2010.

31 See "Judicial Watch Obtains New Border Patrol Apprehension Statistics for Illegal Alien Smugglers and 'Special Interest Aliens", Judicial Watch, March 9, 2011; Edwin Mora, "474 Illegal Aliens from Terrorism Linked Countries Apprehended in 2013 Alone", Breitbart, September 19, 2014.

32 "Breaching America: War Refugees or Terror Threat?" , San Antonio Express News, May 20-24, 2007.

33 "Border Patrol: Checkpoints Contribute to Border Patrol's Mission, but More Consistent Data Collection and Performance Measurement Could Improve Effectiveness", United States Government Accountability Office Report 09-824, p. 27, August 2009.

34 "Border Surge Report", Texas Department of Public Safety report prepared for Gov. Greg Abbott, posted in the body of: Brian M. Rosenthal, "Border surge harming crime fighting in other parts of Texas, internal report finds", Houston Chronicle, February 24, 2015.

35 Department of Homeland Security joint assessment with the California State Terrorism Threat Assessment Center, "Special Interest Alien Use of the California-Mexico Border, Appendix 1: Fiscal Year 2007-08 Special Interest Alien Apprehension Data, August 2009. This document was obtained while the author was working as a journalist in Texas.

36 See Pat and Samir Twair, "Plight of Syrian Refugees Hopeless, Observe Human Rights Attorney, Filmaker", Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, October-November 2013; Alan Gomez, "Report: US-bound Syrians arrested in Honduras with fake passports", USA Today, November 18, 2015; Molly Hennessy-Fiske, "A Syrian Christian, seeking asylum, wonders why he's in custody in Texas", Los Angeles Times, December 20, 2015; Cody Derespina, "Iraqi Christians held for months by ICE after crossing Mexican border in asylum bid", Fox News, August 6, 2015; Molly Hennessy-Fiske, "Syrians' arrival at U.S. border crossing raises concern of a flood of asylum seekers", Los Angeles Times, November 19, 2015.

37 Todd Bensman, "The Ultra-Marathoners of Human Smuggling: Defending Forward Against Dark Networks That Can Transport Terrorists Across American Land Borders", Master's thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, September 2015.

38 See "Texas Public Safety Threat Overview", Texas Department of Public Safety, January 2017, pp. 9-10; David Gauthier-Villars, "Paris attacks show cracks in France's counterterrorism effort", Wall Street Journal, November 23, 2015; Michael McCaul, "Chairman McCaul: The Terrorist Exodus Has Begun and We're Not Ready for It", Fox News Opinion, March 9, 2016; Ryan Browne, "Top Intelligence Official: ISIS to Attempt US Attacks This Year", CNN, February 9, 2016.

39 See "European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2017", European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation, 2017, pp. 6, 12, 14; Dion Nissenbaum and Julian E. Barnes, "Brussels attacks fuel push to close off militants' highway", Wall Street Journal, March 23, 2016; Alan Yuhas, "NATO commander: ISIS spreading like a cancer among refugees, masking the movement of terrorists", The Guardian, March 1, 2016; John Stevens, "How the Paris bomber sneaked into Europe: Terrorist posing as a refugee was arrested and fingerprinted in Greece — then given travel papers and sent on his way to carry out suicide bombing in France", The Daily Mail, November 16, 2015; Isabel Hunter, "Master bombmaker who posed as migrant and attacked Paris last year is now chief suspect in Belgian atrocity as police swoop on home district", The Daily Mail, March 22, 2016.

40 See John Letzing, "Swiss confirm arrest of three Iraqis for suspected support of Islamic State", Wall Street Journal, October 31, 2014; "Somali imam arrested in Italy for planning attack on Rome's main train station", Reuters, March 10, 2016; "ISIS bomb plotter's tour of Britain: Afghan 'refugee' suspected of planning terror attacks used fake IDs to visit high-profile UK sites and posed for pictures as he scouted for targets", The Daily Mail, 11 May 2016.

41 Raf Sanchez, "Islamic State lieutenant captured hiding among fleeing refugees in Turkey", National Post, April 28, 2018.

42 Todd Bensman, "The Ultra-Marathoners of Human Smuggling: How to Combat the Dark Networks that Can Move Terrorists over American Land Borders", Homeland Security Affairs 12, Essay 2, May 2016.

43 Adam MacAllister, Dan Spengler, Kyle Larish, and Nam-Young Kim, "Special Interest Aliens: Achieving an Integrated Approach", Small Wars Journal, undated.