Introduction

Escalating violence highlighted by decapitations, torture, and kidnappings plagues Mexicans, with drug cartel hit men and run-of-the-mill thugs generally targeting their victims. Money, revenge, ransom, extortion, access to drugs, and turf battles often explain these heinous activities. On September 15, 2008, however, a major act of terrorism took place for the first time. Around 11 p.m., as thousands of revelers celebrated the country’s Independence Day in Morelia, miscreants heaved fragmentation grenades into the crowd. When the smoke cleared, eight people lay dead, and more than 100 men, women, and children suffered wounds. TV networks beamed video footage of the blood-drenched scene to unbelieving viewers across the country.

Hundreds of military personnel and federal police flooded in to provide security for shocked citizens and the Attorney General’s Office (PGR) offered $1 million (10 million pesos) for information leading to the capture of the masterminds and perpetrators of the carnage. Still, Deputy Emilio Gamboa Patrón, owner of a super-sized closet of skeletons and a big shot in the once-dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), admitted that citizens were afraid to cooperate with authorities because so many law-enforcement officials were allied with criminal organizations.1 The army, held in higher esteem, may have more success in attracting informants.

Meanwhile, President Felipe Calderón and other dumfounded politicians speculated on who inflicted the wanton slaughter in the picturesque colonial city, 150 miles to the west of Mexico City in the chief executive’s home state of Michoacán.

Were the perpetrators members of the powerful Gulf Cartel, headquartered just below Texas in Tamaulipas state, whose military component is known as Los Zetas? Did they belong to the Gulf Cartel’s chief rival, the Sinaloa Cartel, centered in Sinaloa state, which nestles between the Sierra Madres and the Pacific Ocean? Could they be affiliated with La Familia (The Family) a shadowy drug gang that took credit for hanging seven banners blaming Los Zetas, three members of which have been taken into custody? Might they be guerrillas either in thrall to drug mafias or launching a freelance strike?

Apart from the delinquents’ identity was the ominous possibility that the attack foreshadowed an escalation in the strife: from homing in on specific victims to indiscriminate terrorism as occurred in Colombia two decades ago. The “Morelia massacre” took place barely a week after the bloodiest day in recent memory as sadists carried out 24 executions in Mexico State alone. A prisoner mutiny on September 14 and 17 at Tijuana’s La Mesa prison took the lives of at least 23 inmates and scores of convicts and guards sustained injuries.

These and other atrocities will profoundly change the dynamics of migration flows to the United States, which — contrary to conventional wisdom — have skyrocketed under Calderón, who took office on December 1, 2006. Mexico’s National Population Council (Conapo) recently reported, based on U.S. Census data, that the number of Mexican migrants living north of the Rio Grande grew by 679,611 in 2007 — a five-fold jump over the increase in 2006 (105,347).2

For cognoscenti of U.S. military policy, allusions to “the Surge” spark images of the five army brigades that President Bush dispatched to join 4,000 Marines in order to secure Baghdad and al Anbar province in Iraq. Off the radar screen is the likelihood of “Surge Two” during the months, if not weeks, after the next American president is sworn into office on January 20. This possible movement will entail not weapons-hefting soldiers and Marines in camouflage gear, but hundreds of thousands of T-shirt wearing, backpack-carrying Mexicans seeking to escape mushrooming insecurity at home.

What might induce Mexicans to risk life and limb even though the U.S. economy teeters on the brink of a financial precipice, the employment picture appears grim even for Americans, and state legislatures are amplifying their crackdowns on lawbreakers in response to constituent sentiment? How will the next U.S chief executive and Congress respond to the pressure sure to build on America’s southern border?

Traditional Rules of the Game

During the heyday of the self-proclaimed “revolutionary party,” which held the presidency from 1929 to 2000, drug kingpins cut deals with governors. The Rolex-wearing dons often anted up $250,000 simply to meet with state executives or their interlocutors to attain protection from the various police forces in their bailiwicks. Local law-enforcement chiefs in league with PRI politicians allocated the plazas, areas and corridors where the gangs held sway to produce, store, or ship drugs. They followed a “1-2-3 System”: a pay-off to authorities of $1 million for an interior location; $2 million for a coastal zone; and $3 million for a U.S.-Mexico border crossing. In return for generous bribes, or mordidas, the desperados pursued their illicit activities with the connivance of authorities and in accord with mutually understood “rules of the game.”

Any clashes that occurred among families or between traffickers and police took place in “Mi Delirio,” “Montecarlo,” and other bars in the rough-and-tumble Tierra Blanca neighborhood of Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa. Analyst Leo Zuckermann notes that officials tolerated robberies, but not kidnappings; and that criminals could engage in trafficking, but not in homicides, least of all against civilians. The drug dons acted with civility toward authorities, appeared with governors at their children’s weddings and baptisms, and knew they would suffer deadly consequences if they violated the “live-and-let-live” ethos.

Gradually, the prospect of fattening one’s bank account by selling heroin and marijuana began to alter the unwritten accord between lawbreakers and presumed law enforcers, beginning in Sinaloa. In 1957 the federal police boasted superior firepower over the cartels, whose operatives relied on handguns. A decade later, the drug rings had acquired high-powered weapons, had started mauling each other, and had even begun killing cops — with some shoot-outs taking place in populous areas. Nevertheless, the government still held the whip even though its hand had begun to shake. No semblance of such an authoritarian control mechanism exists today in most Mexican states where the “feudalization” of power reigns.

A “Weak” or “Failed” State?

As never before, Mexican opinion-leaders lament that their country — characterized by strong men and weak institutions in the modern era — risks becoming a “failed state.” For scholar Frances Fukuyama, this status involves two dimensions of state powers — namely, its (1) “scope” or the different functions and goals taken on by governments” and (2) “strength” or the ability of governments to plan and execute policies. 3 Among other things, strong states provide security, law enforcement, access to high-quality schools and health-care, sound fiscal and monetary policies, responsive political systems, opportunities for employment and social mobility, retirement benefits, and transparency. “Weak” states fall short in these areas; “failed” states receive “Fs.”

Indictment of the Mexican State

Fire-breathing Cassandras are not the only ones bemoaning the growing debility of the Mexican state, but thoughtful, influential analysts as well. The pessimism extends even to those who voiced high hopes for President Calderón, an experienced politician, a social-democrat, and a moderate within the center-right National Action Party (PAN) who took office on December 1, 2006.

Luis Rubio, the internationally acclaimed director general of the Center of Research for Development, argued that “our weaknesses as a society are formidable not only in the police and judicial domains, but also in the growing erosion of the social fabric and the absence of a sense of good and bad ….”4

In the same vein, Luis F. Aguilar, an astute and veteran observer, stated with respect to ubiquitous violence: “The public insecurity exhibits the impotence of its branches of government, the futility of its laws and the incompetence of its leaders…. The tragedy is that the decomposition of the State comes from within, largely from its police whose responsibility is to apply the law fairly without exceptions … but the situation of political paralysis and institutional weakness has made us recognize what we really are: a society in search of a State.”5

Meanwhile, Javier Hurtado, a distinguished professor at the University of Guadalajara, addressed the despair of his countrymen who took part in a massive “Light up Mexico” march on August 30 to protest the horrendous criminality and precariousness: “In the face of this situation, citizens find themselves completely vulnerable. It is neither desirable to take justice into their own hands, nor is it possible to continue to putting up with inept leaders.”6

For his part, prize-winning journalist René Delgado averred that: “The people are fed up and disenchanted with institutions. They wish to reclaim the territory lost to the State [to narco-traffickers] with or without the government and [political] parties. And the [current official] gibberish will inevitably crystallize into disaster.”7

Among the factors that buttress the “weak” and “failed state” arguments are mounting brutality; a soaring murder rate; an increase in kidnappings; the venality of local, state, and federal police forces; failure of policy makers to address hazardous conditions; and disenchantment with institutions occupied by officials who live like princes even as 35 percent of Mexico’s 110 million people eke out a living in hardscrabble poverty.

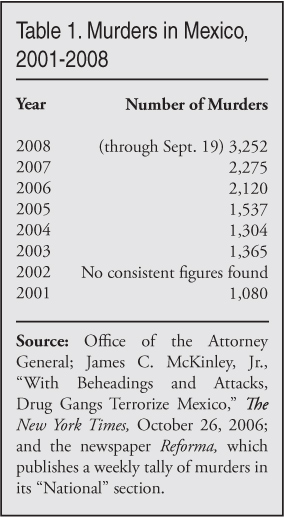

Murder Rate

The figures in Table 1 speak for themselves. Yet the numbers fail to reveal the mounting bestiality of the killings and their locations. Murders often bear the mark of mafia-style executions. For instance, on September 6, 2006, gunmen crashed into the seedy Sol y Sombra nightclub in Uruapan, Michoacán, fired shots into the air, ordered revelers to lie down, ripped open a plastic bag, and lobbed five human heads onto the black and white dance floor. The desperados left behind a note hailing their act as “divine justice,” carried out on behalf of La Familia — once aligned with the Gulf Cartel, the unyielding foe of its Sinaloa counterpart.

The day before the macabre pyrotechnics, the killers had seized their victims from a mechanic’s shop and hacked off their heads with bowie knives while the men writhed in pain. “You don’t do something like that unless you want to send a big message,” said a U.S. law enforcement official, speaking on condition of anonymity.8

Not only have these highly publicized cruelties sparked a “psychology of fear” within the population, they also have conveyed the idea that wrongdoers can act with impunity. Indeed, the government has lost control over portions of its country in a crisis of governability similar to Afghanistan’s.9

Such no-mans’ lands include (1) the Tierra Caliente, a mountainous zone contiguous to Michoacán, Guerrero, Mexico State, and Hidalgo; (2) the “Golden Triangle,” a drug-producing Mecca at the intersection of the states of Sinaloa, Chihuahua, and Durango in the Sierra Madre mountains; (3) the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the Southeast; and (4) neighborhoods in cities along the U.S.-Mexican border where cartel thugs carve up judges, behead police officers, and disappear journalists who incur their wrath. The Paris-based Reporters without Frontiers cited 95 attacks on journalists during the first half of 2008, while a World Journalists’ Report on Press Freedom castigated Mexico as “one of the most dangerous countries for journalists in the world” — with 24 reporters killed, eight missing, and dozens threatened, intimidated, or harassed for practicing their profession during the last eight years.10

Alejandro Junco de la Vega, owner and publisher of major dailies (Reforma, El Norte, Mural, and Palabra), has moved to Texas in response to threats. In a letter to Nuevo León’s governor, the newspaper tycoon said he considers himself a “refugee” and faced the dilemma of either “compromising the editorial line of the paper[s] or protecting my family,” adding that, “We lost faith.”11

Once lauded as the “Pearl of the Pacific,” cynics have informally renamed the famous resort of Acapulco as “Narcopulco” after the numerous murders that have occurred in the area. Savage felonies have also become a nightmare in Tijuana, located just to the south of San Diego, which suffered 49 executions in six days in late September and early October 2008.

Violence afflicts all border states — Baja California, Sonora, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas — where the number of murders has doubled from 732 (2006) to 1,645 during the first nine months of 2008. Chihuahua leads the pack with a jump from 130 to 1,382 during the last 33 months. That state’s largest city, Ciudad Juárez, across from El Paso, Texas, has earned distinction as a grisly killing field. In the past 10 years, 400 women have been the victims of sexual homicides, their bodies often thrown into drainage ditches or empty lots.

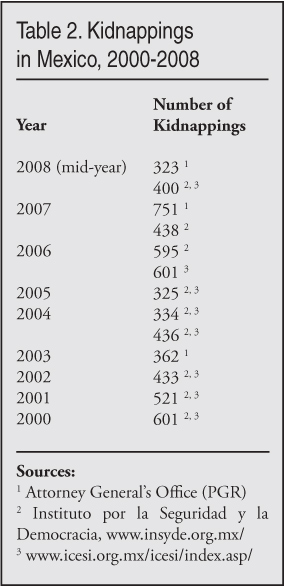

Kidnappings

Almost as disconcerting as the killings are the kidnappings, which have reached epidemic proportions. The rate shot up 9.1 percent during the first five months of 2008 compared with last year, raising the monthly number of abductions to 64.6 from 62.5, according to Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office.12 Table 2 shows the burgeoning number in recent years. However, these data reflect only reported kidnappings. An academic study affirms the conventional wisdom that families do not inform police in up to nine out of 10 abductions because they believe that law enforcement agents and other government officials may be involved in the crimes.13

Especially alarming is the participation of the police in the capture, ransom, and oftentimes liquidation of the victims. A cause célèbre occurred on June 4, 2008, when malefactors snatched from the streets of Mexico City Fernando Martí, the 14-year-old son of the wealthy owner of the largest chain of sporting goods stores in the country. Even though the family bought ads in major newspapers begging for their boy’s freedom and anted up hundreds of thousands of dollars in ransom, on August 1 authorities found the decomposed bodies of the youngster and his chauffeur crammed into the trunk of an automobile.

One of the suspects in this highly-publicized case is Lorena González Hernández, a former deputy inspector of the anti-kidnapping squad of the Federal Preventative Police (PFP), who had worked in one or more federal law-enforcement agencies since 1999.14

Just three days before the discovery of young Fernando’s corpse, a family of six was found dead in their home in western Jalisco state, allegedly targeted by kidnappers who were aided by corrupt cops. The killers shot four victims in the head, including two children, slashed the throat of a teenage boy, and asphyxiated his mother with a plastic sack.

To show hostility toward the government and evince solidarity with the grief-stricken family, more than 150,000 people, dressed in white and lofting candles, marched through the center of Mexico City on August 29. But there seems no way to convert grassroots’ seething into major changes in public policy. “We are prisoners in our own homes,” said Maricarmen Alcocer, a housewife. Another protester, whose daughter was kidnapped in 2004, added, “They are more bloodthirsty, they make their victims disappear, they mutilate them, they cut their ears off just as in the case of my daughter. We do not know where she is.”15

The outrage is ubiquitous. “They should put their eyes out, so they can’t commit any more crimes,” bemoaned Ignacio Noriega, who says he no longer feels safe anywhere. “Prison isn’t a solution anymore. They just form their own gangs inside prison and come out stronger,” the 26-year-old university student told a reporter.16

“Express kidnappings” have gained popularity in Mexico’s murky underworld. Although the victims generally survive, these acts often begin when a passenger climbs into one of the tens of thousands of unauthorized or “pirate taxis” whose owners bribe officials in Mexico City and elsewhere. The driver or his accomplice whips out a knife or gun and demands credit cards, cash, jewelry, cellular phones, or immediate withdrawals from ATM accounts. Once the loot is obtained, they often release the fear-stricken victim. In addition, “[o]ne increasingly disturbing spin is that the criminals may contact your family and not release you until a hefty ransom is paid.”17

Failure of Government Officials

In reaction to the palpable, deep-seated outrage against ascending violence, President Calderón affirmed in his September 1, 2008, state of the nation address: “I wish to tell you that my Government will continue working every day to find and apply solutions for the issues that most worry you and your family. The goals of transforming Mexico require the effort and commitment of all. We have problems, yes; we are confronting them, and we are going to overcome them and move ahead.”18

While nodding their approval, moguls in the audience continue to fork over millions of pesos for armored cars, professional drivers, bodyguards, weapons, alarm systems, sophisticated locks, security consultants, micro-chip implantations in family members, and other protective devices.

The chief executive’s optimistic words aside, the likely response of policy makers will be “Punishment Populism” (“Populismo Penal”); namely, posturing over proposals that appear to get tough on criminals, but that will be more rhetorical than real.

All told, some 75 proposals emerged for discussion at Mexico’s National Public Security Council (NPSC). Calderón’s controversial Secretary of Public Security, Genaro García Luna, presides over this body, which also embraces the secretary of national defense, the secretary of the navy, the secretary of communications and transport, the attorney general, the mayor of Mexico City, and the 31 governors. Its purpose is to coordinate anti-crime ventures in the various jurisdictions among which there is, at best, a modest exchange of information and intelligence.

NPSC is considering imposing life-in-prison sentences for malefic acts, compensating kidnap victims’ families, outlawing payments to kidnappers, combating corruption, encouraging neighborhood-watch groups, cleaning up the judiciary, offering anonymity (and even stipends) to informants, and tracking the numbers of cell phones used in the commission of felonies.

Yet, even the wisest and best-intentioned initiatives will founder in the absence of professional and honest law-enforcement officers.

Police Reform: A Will-o’-the-Wisp?

Angst-ridden Calderón, who has dispatched 30,000 members of the military and federal police to combat drug cartels, appears like a deer caught in the headlights of four on-rushing tractor-trailers: street violence, the drug mafia, the spillover from the U.S. economic debacle, and the rabble-rousing of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (discussed below).

The chief executive is searching for a silver bullet in the form of a single force to replace the roughly 3,000 local, state, and federal law-enforcement agencies. In theory, this body would recruit assiduously vetted men and women, who would be meticulously trained in modern techniques, infused with respect for human rights, garbed in spiffy uniforms, awarded decent pay and benefits, and provided credits to acquire decent, affordable homes. To begin with, he is determined to merge the Federal Preventative Police (PFP), formally under the Ministry of Public Security, and the Federal Investigative Agency (AFI), a dependency of the Attorney General’s Office that fancies itself the local version of the FBI.

The president has boosted by some 30 percent funds in his proposed budget to fight rampant street crime and accelerate the pursuit of the sadistic, well-heeled narco-barons who operate major and minor cartels. Nevertheless, he and García Luna face rigid resistance to spawning a coherent national police unit. Foes include governors, elements of the military, some Security Cabinet members, and key lawmakers who have yet to approve the consolidation. Critics gained more ammunition in late September 2008, when the government had to summon 300 members of Federal Preventative Police to oust approximately 100 AFI officers who had occupied their agency’s headquarters to protest the PFP-AFI consolidation.

As important as money may be, the resources contemplated for 2009 are a drop in the bucket compared with the funds required to hire enough honest investigators to conduct background checks, psychologists to assess personality traits, polygraph operators to ferret out liars, drug-testing specialists to identify addicts, human-rights experts to inculcate respect for civil liberties, and law-enforcement professionals to examine thoroughly and train a cadre of tens of thousands of well-paid new recruits.

Suppose that lightening struck or the Virgin of Guadalupe reappeared to create a lean-clean-crime-fighting machine. How long would the new gendarmes remain pure? Would displaced cops forego minor shake-downs to engage in venal acts of gangsterism? The suggestion that the government will keep tabs on these ousted bad actors lies in the realm of fantasy. In all fairness, however, homes of their own could provide good officers with a stake in the community as well as a means for superiors to observe unexpected life style changes that could signal illicit behavior.

Business-as-usual will find the August 30 marchers — and their sympathizers from the Rio Grande to the Guatemalan border — casting ballots for the PRI and other opposition parties in the mid-2009 deputy contests to protest the surging insecurity. On October 5, the revolutionary party clobbered the leftist-nationalist Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) in Acapulco and other areas of impoverished Guerrero state.

The PRD’s mayor of Mexico City, Marcelo Ebrard, who is eager to succeed Calderón in 2012, has borne the brunt of shrill criticism over the Fernando Martí affair. The apprehension of the teenager’s possible abductors may have stanched his hemorrhaging approval rating, but his presidential prospects appear bleak.

Calderón and his PAN could bounce back if, as widespread rumors indicate, the armed forces manage to snag a couple of cartel über-lords from the Gulf and Sinaloa cartels. Better still, would be for him to seize upon the Morelia tragedy to kindle national unity, anti-cartel animus, and cooperation among intolerant politicians who view their adversaries as enemies rather than the loyal opposition.

Above all, he should spurn using the bilateral border as an escape valve for those seeking opportunities and safety. Instead, he should emphasize his nation’s vast physical, natural, industrial, and human wealth, demand that the elite pay taxes to finance social programs, and smash the bottlenecks in oil, electricity, telecommunications, education, and health-care that thwart the mobility of the masses while impeding the country’s ability to compete in the global marketplace.

The failure of Mexico’s leader to turn this latest assault on decency into a Mexican version of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first “100 Days” will heighten chances for a PRI majority in the Chamber of Deputies next year and leave Calderón fluttering as a lame duck three years before the next presidential contest.19 Meanwhile, the boyishly handsome, well-financed PRI governor of Mexico State, Enrique Peña Nieto, is positioning himself as a muscular crime-buster. And even he must contend with the distaste for political figures and official institutions.

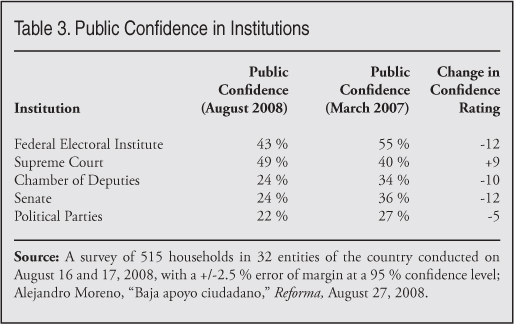

Disenchantment with Institutions

Table 3 shows the public’s plummeting confidence in major judicial and political organizations over the last 18 months. Affected by these declines are:

- The Federal Electoral Institute (IFE). Organizes, monitors, and counts votes in national elections. In the aftermath of the viciously-disputed 2006 presidential showdown — populist-nationalist López Obrador officially lost by less than 0.56 percent out of nearly 42 million votes cast — Congress has reduced IFE’s prerogatives and curtailed its functions.

- The National Supreme Court of Justice (SCJN). Serves as the nation’s highest court on all matters except electoral appeals. Several justices, who meet openly with powerful legislators, appear to circumvent the constitutional system of checks and balances. The chief justice, whose income greatly exceeds that of the president ($237,770.84), receives $371,900 in salary and benefits, while his 10 colleagues collect $362,400 annually. All enjoy lavish retirement benefits.20 While the SCJN exhibits reasonable professionalism, Transparency International found that 80 percent of Mexicans perceived the judicial system to be corrupt.21

- The Senate. Controlled by the PRI’s Manlio Fabio Beltrones Rivera, who is the nation’s virtual vice president in terms of his influence, the Senate often finds itself at loggerheads with the executive branch with predictable gridlock. Senator Beltrones and many of his colleagues have lambasted Calderón’s anti-crime gambits, but — in the wake of the Morelia catastrophe — are eager to pony up more money for security.

- The Chamber of Deputies. Although there is no dominant force like Beltrones in the lower house, Calderón’s opponents are loath to give him and his National Action Party any assistance that would loft their star in the mid-2009 legislative races. As is the case in the Senate, though, deputies are now falling all over each other to endorse anti-crime provisions in the next budget.

The messianic López Obrador, who refuses to recognize Calderón’s victory in 2006, has anointed himself the nation’s “legitimate president” and, with members of his 12-member “legitimate cabinet” (his version of the 12 apostles) continues to barnstorm the country. During his tours, he crudely mocks the chief executive’s programs, policies, and personnel. As the savior of the poor, the populist López Obrador — a member of the badly-divided PRD — has exhorted leftist legislators to oppose reforming Mexico’s energy sector. He threatens to unleash mayhem if there is an attempt to privatize components of Petróleos Mexicanos, the inefficient, featherbedded state monopoly, whose reserves are dwindling.

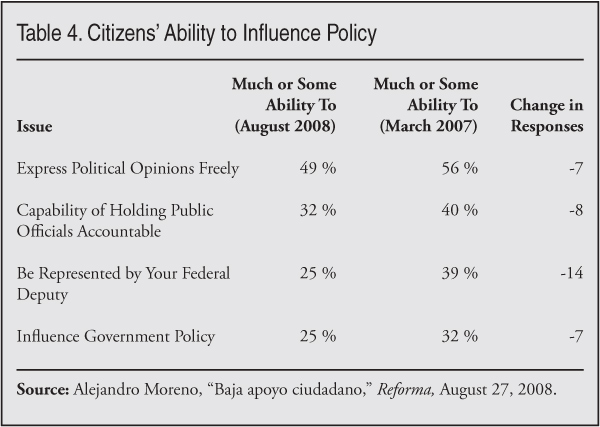

Table 4 shows the citizenry’s ever greater sense of impotence to influence policy and policy makers. The indifference of officials to voters springs from several factors, including a constitutional ban on the reelection of chief executives, the selection of half the Senate and two-fifths of the Chamber of Deputies by proportional representation so that they lack defined constituencies, and the prohibition on deputies, senators, governors, state legislators, and mayors serving consecutive terms in the same office.

Still, ambitious men and women can hop aboard the carrousel by, say, leaving a deputy’s seat to become a senator before serving in a state legislature on the way to winning a post in the capital’s city council en route to occupying a statehouse. This makes politicians beholden to cash-dispensing and nominee-choosing party power brokers — much more than to the public — for their next post. The heads of party factions in legislative bodies spend millions of dollars at their own discretion to promote allies and punish foes. Former Sinaloa governor Juan S. Millán tells the story of a PRI stalwart who won a deputy’s seat in Veracruz several decades ago. He visited a remote part of his district and promptly told those assembled to hear their “representative”: “Take a good look at my face because you are never going to see it again in this fly-specked, chicken-shit little village.” 22 Forging close ties to media conglomerates — as Governor Peña Nieto has done —also yields rich political dividends.

The most disturbing indicator lies in the “satisfaction” or lack thereof that a cross-section of the public has with respect to the “functioning of democracy in our country.” In March 2007, the 50 percent satisfaction level overshadowed the naysayers by 10 points; in August 2008, in the aftermath of a tsunami of street crime and narco-violence, only 36 percent of respondents claimed to be “satisfied” with democracy vis-à-vis 54 percent who voiced discontent.

At the same time, 63 percent of respondents expressed approval for the armed forces (down from 70 percent last year), 23 which Calderón has thrust to the forefront of Mexico’s drug war and whose retired officers play key public safety roles in many states and municipalities. Despite a number of spectacular successes by the military, the longer it spearheads the battle against the cartels, the more likely its personnel will be corrupted, experience a loss of morale, or become fatigued. “We work 365 days a year. From generals to grunts, we all have a right to a vacation,” said a Sinaloan general with 42 years of service. 24 Higher compensation notwithstanding, desertions, which totaled 107,128 soldiers between 2000 and 2006, 25 continue unabated with approximately 42,000 men and women fleeing their barracks between Calderon’s inauguration and mid-2008. Human rights organizations lament a rise in military-inflicted abuses. 26

Immigration Policies of The Next U.S. President?

In their battle to win the White House, Democrat Barack Obama and Republican John McCain have given lip-service to gaining control of the U.S.-Mexican border before attempting to reform America’s immigration statutes.

The platform adopted at the Republican National Convention also expressed opposition to amnesty, stating: “The rule of law suffers if government policies encourage or reward illegal activity. The American people’s rejection of en masse legalizations is especially appropriate given the federal government’s past failures to enforce the law.”

The Democrats articulated a softer line: “For the millions living here illegally but otherwise playing by the rules, we must require them to come out of the shadows and get right with the law. We support a system that requires undocumented immigrants who are in good standing to pay a fine, pay taxes, learn English, and go to the back of the line for the opportunity to become citizens.”

As John Nance Garner, who served under Roosevelt, allegedly said about the vice presidency, party platforms are “not worth a bucket of warm spit.” On the campaign trail or in office, politicians regularly take their party’s directives with a grain of salt.

Such will be the case with immigration. After all, Barack Obama enthusiastically backed the McCain-Kennedy bill to award virtual amnesty to illegal aliens living in the United States on January 1, 2007.

The legislation, which ultimately died last year, would have given unlawful newcomers a “Z visa” that granted its holder the right to remain in the United States for the rest of his or her life, access to a Social Security number, and — after eight years and the payment of a fine and back taxes — a “green card” or permanent residence document that would propel him or her on to the path toward citizenship. As chief executive, neither Obama nor McCain is likely to have the same commitment to enforcing immigration statutes as vigorously as has the Bush administration in the last year or two.

No matter who captures the White House, several factors militate against the occupant’s assigning a high priority to this divisive issue early in his administration. To begin with, the next president will have to try to bring order to an economic eruption whose shock waves reverberate around the world. He also must contend with the conflict in Iraq, where violence has fallen thanks to additional troops, and Afghanistan, where conditions have gone from bad to worse.27 Pressure will build for initiatives in energy, health insurance, infrastructure, and other unmet domestic needs.

Reinforcing these considerations will be the imperative to find or create opportunities for Americans, especially the less-educated who face competition for jobs and decent wages from immigrants. Special pleaders for expanding guest-worker programs, granting additional visas, and bestowing some form of amnesty to illegal aliens have gained the ear — and often the support — of elites in the nation’s capital. At the same time, officials who serve on city councils and in state legislatures are receiving a different message from the taxpayers — specifically, the two-thirds of Americans who believe that the number of illegal immigrants in the country should be reduced (only 5 percent favor an increase).28

The message from Main Street in contrast to that from “the K Street corridor” of lobbyists is: “Let’s enforce the laws against illegal immigrants now on the books, penalize employers who exploit them, enhance border security, and make a serious effort to curb unlawful border crossings.”

The September Time of Troubles will slash federal funds available to states and localities that are already straining to fund education, healthcare, law enforcement, and social services. The proverbial “man in the-street” will rebuke members of city councils and state legislatures who seek to use taxpayer dollars to reward those who have sneaked into the country or entered legally only to overstay their visas and disappear into the shadows.

Even as the so-call “pull factors” may recede in importance, the “push factors” — accentuated by the severely weakened state presided over by Calderón, the toxic spillover into Mexico of its northern neighbor’s financial crisis, and a nose-dive in remittances — will tempt fear-ridden Mexicans to seek a safe haven in the United States. In contrast to Iraq, they will be fleeing violence, not attempting to extinguish it.

How will the next putative leader of the free world react to a possible Second Surge? Will he turn a blind and patronizing eye to the callous behavior of Mexico’s pampered grandees or will he insist that they marshal their cornucopia-shaped nation’s boundless resources to inspire hope in and uplift the long-neglected downtrodden, who — absent inspired leadership — could flock to an irresponsible redeemer like López Obrador in the next presidential showdown?

End Notes

1 Jesús Guerrero, “Crítica Gamboa recompense de PGR,” Reforma, September 21, 2008.

2 Silvia Garduño, “Crece con Calderón la migración a EU,” Reforma, September 21, 2008.

3 Francis Fukuyama, “The Imperative of State-Building,” Journal of Democracy 14 (April 2004): 17-31.

4 Quoted in Luis Rubio, “Violencia,” Reforma, June 8, 2008.

5 Quoted in Luis F. Aguilar, “En busca del Estado,” Reforma, August 13, 2008.

6 Quoted in Javier Hurtado, “México secuestrado,” Reforma, August 14, 2008.

7 René Delgado quoted in “Un país inseguro,” El Siglo de Torreón, August 30, 2008.

8 James C. McKinley Jr., “Mexican Drug War Turns Barbaric, Grisly,” The New York Times, October 26, 2006.

9 “Más operativos, más violencia,” Proceso, July 20, 2008.

10 “Shocking Culture of Impunity and Violence,” http://www.freemedia.at/cms/ipi/statements_detail.html?ctxid=CH0055&doci....

11 “Por qué se fue Alejandro Junco,” Reporte Indigo, September 12, 2008, http://download.reporteindigo.com/ic/pdf/98/reporte.pdf.

12 “Secuestran a dos personas al día en promedio: PGR,” El Imparcial (Hermosillo), September 15, 2008.

13 Researchers at Mexico’s National Autonomous University (UNAM) reported a 90 percent non-reporting rate; see Barnard R. Thompson, “Kidnappings are out of Control in Mexico,” Mexidata.Info, June 14, 2004, http://mexidata.info/id217.html.

14 Zemi Communications, “Mexico, Politics and Policy,” September 9-15, 2008, http://www.zemi.com/articles/pdf/Zemi-Newsletter09-15-08.pdf.

15 The quotations appeared in “Over 150,000 March in Mexico against Crime,” Reuters, August 31, 2008.

16 Quoted in Mark Stevenson, “Mexico Outraged over Corrupt Police, Kidnappings,” Associated Press, August 21, 2008.

17 Quoted in Solutions Abroad, “Kidnappings in Mexico,” http://www.solutionsabroad.com/en/security/security-category/kidnapping-....

18 Gobierno de México, Segundo Informe, September 1, 2008, http://www.presidencia.gob.mx/prensa/?contenido=38296.

19 The PAN now holds 207 seats in the Chamber of Deputies well ahead of the PRD (127 seats), the PRI (106 seats), and minor parties (60 seats); at the same time, the PAN boasts 52 senators compared with the PRI’s 33, the PRD’s 26, and minor parties’ 17. There will be no new senators elected until 2012.

20 Reported by Katia D’Artigues, “Campos Elíseos,” El Universal, March 19, 2007, www.eluniversal.com.mx/columnas/64164.html.

21 Transparency International, Global Corruption Report 2007 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), http://www.transparency.org/publications/gcr/download_gcr/download_gcr_2007.

22 Juan S. Millán, Interview by author, July 9, 2004, Mexico City.

23 Alejandro Moreno, “Encuesta/Baja apoyo ciudadano,” Reforma, August 27, 2008.

24 Quoted by Malcolm Beith, “Tough Habit to Break,” Newsweek Web, June 12, 2008, www.newsweek.com/id/141227.

25 Testimony of Defense Secretary Guillermo Galván Galván before the Chamber of Deputies on April 25, 2007; see also, Stephanie Hanson, Backgrounder: Mexico’s Drug War, Council on Foreign Relations, June 28, 2007, http://www.cfr.org/publication/13689/mexicos_drug_war.html.

26 Sara Miller Llana, “Military Abuses Rise in Mexican Drug War,” Christian Science Monitor, June 24, 2008 www.csmonitor.com/2008/0624/p06s01-woam.html.

27 See testimony by Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman, Admiral Mike Mullen and Robert Burns, “Defense Chiefs: Afghan Fighting is Getting Harder,” The Washington Post, September 10, 2008.

28 NN/Opinion Research Corporation, January 14-17, 2008; Survey involved 1,393 adults nationwide and had a plus or minus 3 percent margin of error, http://pollingreport.com/immigration.htm.

About the Author

George W. Grayson, the Class of 1938 Professor of Government at the College of William & Mary, has made 180 research trips to Mexico. He is a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic & International Studies; an associate scholar at the Foreign Policy Research Institute; a board member of the Center for Immigration Studies; and a regular lecturer at the Foreign Service Institute of the U.S. Department of State. His last book was a biography of Mexico’s self-proclaimed “legitimate president” Andrés Manuel López Obrador entitled Mexican Messiah (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007). His next book, Mexico’s Struggle with “Drugs and Thugs” (Foreign Policy Association, New York) will be published November 1, 2008.