Click here to download a pdf version of this Backgrounder

David S. North is a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies.

The American tradition, over the years, has been that the first generation of immigrants struggles, the second generation does better, and the third generation does even better in terms of income, education, personal health, and overall achievement. There is much statistical as well as anecdotal evidence of these trends in the past.

Currently, however, social scientists are finding that this overall pattern is not happening with the second and following generations of more recent immigrants; on many measures, the follow-on generations do not achieve as much as their forefathers, the immigrants. Interestingly, the scholars making these findings are deeply sympathetic with both the immigrants and their descendants; there is no stacking of the social science deck here.

These are some of the signs, many of them identified at a recent conference1 on the subject, of what has been termed the immigrant paradox:

- Success in the education system declines from the first to the third generation, although knowledge of English rises sharply over the generations.

- Violence and drug abuse rises among later generations.

- Risky sexual behavior increases from the first to the third generation.

- When socioeconomic standing is taken out of the equation, the health of children in most immigrant groups gets worse from the first to the third generation.

- Among the descendants of the original respondents in a 1965 survey of Mexican-American immigrants to the United States, a follow-on study in 2000 showed flat earnings and homeownership patterns for the second through the fourth generations.

- The trends noted above play out differently with different immigration flows; they are decidedly the case with Latin American immigration, the largest of the immigrant streams, but do not hold, generally, with the smaller flow of Asian immigrants, or the even smaller group of migrants from Europe.

Traditional Patterns

The anecdotal evidence of the traditional path of immigrant descendants is probably more significant politically than the statistics that chart the same course. People relate better to stories about other people than they do to numbers.

A good example is that of the Goldwater family. The first generation, a poor migrant from Poland known both as Michael Goldwasser and Michael Goldwater, came to Arizona and started several dry goods stores. His son, Morris Goldwater, built the small stores into leading department stores, and became Mayor of Prescott, Ariz. The third generation, the grandson, Barry Goldwater, was a general during World War II, was repeatedly elected senator from Arizona, and was his party’s candidate for President in 1964.2

On a much more modest level, my own family followed the same pattern. The immigrant came to Wisconsin as a teenage farm laborer before the Civil War and died a farm owner. His son, the second generation and my grandfather, was a small-town businessman, was nominated by the usually predominant party for the state legislature,3 and died owning two farms. My father, Sterling North, became a well-known writer, published about 20 books, won various literary awards, saw two of his books become Hollywood films, and died a millionaire.

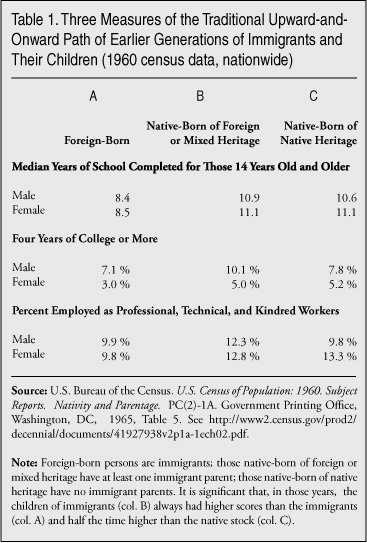

There are plenty of statistics to document the workings of this traditional pattern. See, for instance, Table 1, which is drawn from the 1960 census. It shows three variables: median years of school completed, four years of college or more, and the percent employed in professional, technical, or kindred jobs. For each variable, the second generation (native-born of foreign or mixed heritage) outshone the first generation, the immigrants, and usually by substantial margins. For instance, 7.1 percent of the immigrants completed four of more years of college, as compared to 10.1 percent of the next generation.

That old pattern seemed, on the face of it, to be highly plausible. The immigrants arrived in a strange land and did not do as well economically and socially as the natives; the immigrants’ children, however, benefitted from growing up in the United States, did not have their parents’ linguistic problems, worked hard, and prospered. In short, the melting pot functioned well, at that time, for the second and subsequent generations.

As time passed, and larger and larger waves of immigrants arrived, the traditional pattern dissipated, though this was not noticed because of a little-known, and unfortunate, statistical policy decision. For 70 years, through the 1960 census, the Census Bureau published data on three groups of people: the foreign-born; those born in the United States of foreign or mixed parentage; and those native-born to native-born parents. (By mixed parentage the Census Bureau meant those born to one immigrant parent and one native-born parent.)

This useful set of data came to an end following the 1960 census; all the reports since divide residents of the nation into just two nativity categories: the foreign-born and everyone else,4 eliminating the near century-long data set on the children of immigrants. So what happened to the second generation, which was so well documented in the past, is no longer routinely recorded in the census.

Why did this reporting change happen? I was engaged in immigration policy research at the time and recall — but cannot document — that someone from the Census Bureau explained to me that heavy pressure from Hispanic interests caused the Bureau to publish much more data, starting in 1970, than previously about that segment of the population. In order to finance the extra work something had to give, and it was the series of reports on nativity.5

So, if one is interested in the adaption rates of immigrants’ children one has to turn to data sets other than the census; scholars have begun to do this in last couple of decades. Unfortunately, unlike the earlier series of data, the current ones have differing definitions; as a result, the story of the fading achievement record of the children of immigrants is blurred.

Interestingly, the traditional American pattern of adaptation over the years, which we will call the Goldwater pattern, is the norm around the globe. In other nations of immigration, “The first generation does worse than the second and the third generation.” The only exceptions, according to one expert, who examined data from more than 40 nations, are the United States, Australia, and New Zealand.

These statements were made by Prof. Suet-ling Pong of Penn State, as quoted in the Education Week6 coverage of Brown University’s March 6-7, 2009, conference “The Immigrant Paradox in Education and Behavior: Is Becoming American a Developmental Risk?”

The attitude of the organizers is telegraphed in the conference’s subtitle, but a large amount of useful information was generated by the session nonetheless.7

Newer Patterns

What happens to the children of immigrants matters, not only to them, but to the larger community. As several of the conference speakers pointed out, while 10 percent of the total population is foreign-born, the ratio of children of immigrants to all U.S. children is much larger; 22 percent, 23 percent, and nearly 25 percent by various speakers’ estimates. The relative youth of the immigrant population, its rapidly increasing size, and its higher fertility rates than natives all help explain why such a large proportion of school children have one or more immigrant parents.

While the significance of immigrant children to the nation as a whole is considerable, it is even more so in our cities and other immigrant-impacted areas. Immigrant children are likely disproportionately represented in public schools; similarly there are not many of them in rural or mountainous areas, so they are very numerous in the big city public schools.

The reports on this large and rapidly growing population are anything but encouraging.

Several of the speakers discussed the two-edged sword of acculturation of the immigrants’ children to the larger population. Prof. Cynthia Garcia Coll, of Brown, the conference organizer, pointed out: “as the kids acculturate ... they lose the protectiveness of their home.”

She went on to say that as they speak better English, they do less homework and “they start to buy into the notion of minorities here that even if you work hard and play hard discrimination is going to get at you” (and presumably discourage you from trying harder).8 Further, as time passes the immigrants’ children progressively learn more from their peers, some of whom are gang members.

Donald J. Hernandez, a sociology professor at SUNY-Albany, said that immigrant students were less likely than students in later generations to be diagnosed with learning disabilities. He also said the math scores for Mexican-heritage children declined from the first to the third generations, but that English speaking abilities increased.

Hernandez, moving from education to adolescent behavior, told the conference that violence and substance abuse increased from the first generation of immigrant children to the third, though this was not the case with those of Chinese descent.9

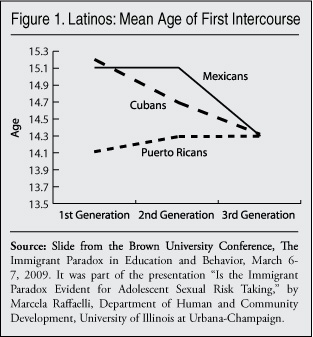

Similarly, the passage from the first to third generations of immigrant descendants was marked by the lowering of the average age of the first act of sexual intercourse and other signs of risky sexual behavior. That age dropped from 15.1 years for first generation Cubans and Mexicans in one study to 14.3 years in the third generation (see Figure 1).

These data were presented by Marcela Raffaelli, a professor in the Department of Human & Community Development, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her funding source for the work was unusual for the immigration field: the Extension Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Hernandez also reported that the health of most immigrant groups went downhill, when socio-economic factors were held constant, from the first to the third generations. For example, using regression analysis, he showed that the second generation of children of most overseas migrants were more likely to be obese than those in the first generation, with the third generation being even more likely than the second to be substantially overweight. He said that Cubans and Mexicans were particularly likely to experience this problem.

One of the papers at the conference will probably be a disappointment for those concerned with the differential life outcomes of immigrants as opposed to their children. It was a comprehensive study of perhaps 45,000 New York City grammar school students,10 conducted over a period of eight years, and recording a plethora of math and reading scores.

The study represented a golden opportunity — but a lost one. The problem was that within this study the two populations of interest — like those in the decennial census — were immigrants and all others, with no sorting of the children of immigrants from the children of the native-born.

The findings were that immigrant students did better, often far better, than anyone else in the system.11

It was not only the Brown University Conference participants who have noticed and documented the Immigrant Paradox pattern. One of the most interesting recent studies of immigrant children grew out of an incident in Los Angeles. In happy contrast to the story about the Census Bureau eliminating reports on immigrant children as a class, someone made a discovery about 17 years ago at the Department of Sociology at the University of California at Los Angeles.12 It was the original file, now dusty, but still legible, with respondents’ names and addresses, from the 1965 Mexican American Study Project. That was a major, pioneering effort at the time backed by a lot of Ford Foundation money that provided much new information on this population.

Edward E. Telles, a professor of sociology and Chicano studies, at UCLA, and Vilma Ortiz, associate professor in the same establishment, decided to use this material to try to find the original respondents, and their descendants, to see how they had fared in the United States.13

Among their many interesting findings were the flat levels of educational and economic achievement among the follow-on generations, the descendants of those initially surveyed in the 1965 project.

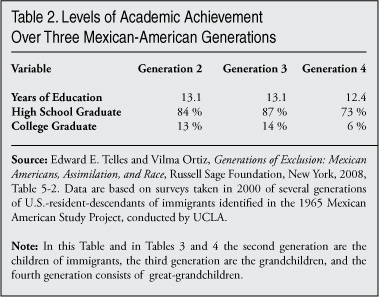

As to education, Telles and Ortiz write: “Most social scientists who have closely examined schooling data for Mexican Americans over generations since the immigration of their ancestors have shown that the educational attainment improves from immigrant parents to their children, but stalls between the second and third generations.”

Citing their own survey, they note: “High school completion is similar among all three generations since immigration, and college completion is noticeably lower for the fourth generation (6 percent) though it is not appreciably different between the second (13 percent) and the third (14 percent) generations (see Table 2).

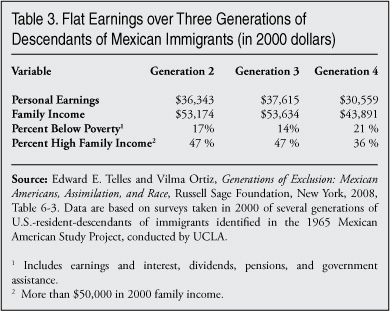

After noting the close connection between education and success in the labor market, the two authors also wrote: “Overall [economic] improvements for Mexican Americans in that period [1965-2000] thus mostly benefitted those closest to the immigration experience. Among subsequent generations, the second and the third had similar earnings and were somewhat higher than those of the fourth generation, though … income and earnings for the fourth generation do not differ significantly from those of the second and third generations, once appropriate factors are controlled.” (See Table 3, which is drawn from their study.)

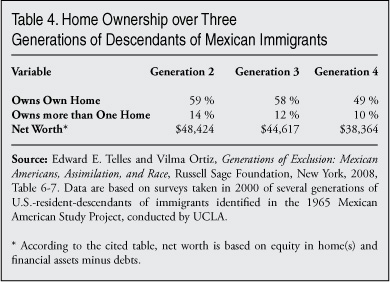

Other measures of economic success are home ownership and net worth; both, by definition, reflect earnings by the family involved, and their ability to save. Again, the two authors report no progress over the generations of immigrant descendants. Home ownership, which in 2000 was reported by 73 percent of the original respondents (immigrants) was reported at 59 percent for Generation 2 (children of immigrants), and decreased thereafter (see Table 4).

Not all of the current set of immigrant children fall into the plateau effects we have been describing; those from Asia are particularly likely to get higher scores in the immediate, post-immigrants generations. This conclusion was noted by, among others, Min Zhou, another UCLA professor at the conference. She told of the Chinese community-created after-school programs in Los Angeles that help second-generation Chinese do well in high school, and commented that no similar programs had been set up by the nearby Mexican American communities.14

Why the Change?

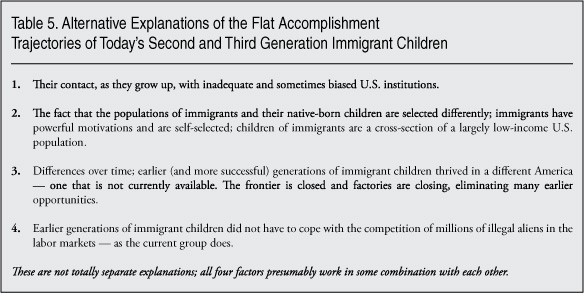

The conference speakers, as well as Telles and Ortiz, first stress the failures of various aspects of the host nation to explain the Immigrant Paradox.

They say that ill-funded and uninspired inner-city schools, programs for ethnic minorities that are not “culturally competent,” an inadequate medical care system, the recently decentralized and sharply reduced welfare system, the lack of appreciation for immigrants generally, and other lingering biases in the society all tend to slow the progress of the children of immigrants. (The skin color mix of the arriving immigrants of 50 years ago is, everyone agrees, different than the current one.)

The overall notion appears to be that the follow-on generations are among the more vulnerable members of society, and when society does not function well, the immigrant children are more likely to be hurt than others. Another factor, regarding economic outcomes, not stressed by these commentators, would be the deepening divide between the rich and the poor, aggravated in recent years by an administration which, among other things, kept the minimum wage low and made sure that its enforcement was thoroughly subdued.15

It may be with all these thoughts in mind that Telles and Ortiz titled their report Generations of Exclusion: Mexican Americans, Assimilation, and Race. Similarly, Portes and Rumbaut’s book on the immigrant second generation, Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation, carries a chapter heading: “Not Everyone Is Chosen: Segmented Assimilation and Its Determinants.”

Telles and Ortiz focus on what they regard as the failure of the U.S. school system: “For Mexican Americans, the payoff can only come by giving them the same quality and quantity of education as whites receive. The problem is not the unwillingness of Mexican Americans to adopt American values and culture, they argue, but the failure of societal institutions, particularly the public schools, to successfully integrate them as they did the descendants of European immigrants.”16

Those taking this analytical approach to the immigrant paradox have a matching set of policy recommendations, such as investing more in preschool education, supporting bilingual education, strengthening after-school programs, and learning from successful immigrant communities what those communities have done to help their own people.17

A second overall explanation of the shortfall of the second and third generations is that the two populations — immigrants and children of immigrants — were selected in very different manners.

The immigrants, like immigrants world-wide since the beginning of time, are self-selected. They are the subset of a home-country population that has the fortitude and the ambition to leave the community of their birth to go to a strange place where they think they will lead better lives. Immigrants, except those in some refugee situations, are not a random sample of the land of their birth; they have enough disadvantages (educational and economic) to want to change their lives, but they have the more-than-compensating advantage of the assertiveness to do something about their situation.

It is generally recognized that they carry their upward-and-onward beliefs and value systems when they migrate, and uphold them for the rest of their lives, even though they have moved to a different nation, and a different culture. It is no wonder that the immigrants score higher than some other populations — such as their own children — on a large number of variables. Similarly, they are less likely to engage in the risky behavior of others living in the inner cities.18

On the other hand, the children of immigrants are not self-selected. They are simply born into, usually, a low-income community in the United States, and (as the conference organizers emphasize) have been subject to the usual stresses and temptations and discriminations of growing up in what we used to call slums. They, much more so than their parents, are vulnerable to the social pressures of such places to not do well in school and to fit in with the life-patterns of their low-income peers.

It would be hard to imagine such a population doing better than average in any setting, in any nation, and, as the scholars are now discovering, they have behaved as might be expected.

A third explanation relates to the nation where the children of immigrants grow up; it is not the same America that was experienced by earlier generations of immigrants and immigrants’ children. The frontier closed more than a century ago and, for the last half-century, factories have been closing in the United States. There are simply not as many opportunities for the lightly educated as existed in the past,19 and this message discourages many from trying to shake off the pressures from their often wayward, native-born teenage peers. It certainly does not help them follow their parents’ and grandparents’ path toward upward mobility.

A fourth explanation of the change away from the Goldwater family pattern is rarely, if ever, mentioned in the literature. That is the fact that the children of recent immigrants to the United States, particularly the children of recent (post-1960) Mexican immigrants, face direct labor force competition from millions of illegal immigrants, often geographically located in the same areas favored by the children of immigrants. Children of immigrants arriving in the century before 1960 rarely faced this competition.

That competition from eager, even desperate, illegal workers keeps wages low and opportunities for upward movement severely limited. This effect was, and is, felt by both the illegal workers themselves, and by their competitors, many of whom are the children of legal immigrants.

Presumably all four of these factors — in varying combinations — are at work to limit and slow the upward mobility of today’s immigrant children.

End Notes

1 Mary Ann Zehr, “Scholars Mull the ‘Paradox’ of Immigrants: Academic Success Declines From 1st to 3rd Generation,” Education Week, vol. 28, no. 25, March 18, 2009, pp. 1 and 12. The conference was entitled: “The Immigrant Paradox in Education and Behavior” and was held at Brown University on March 6-7, 2009.

2 See the Goldwater family entry in http://politicalgraveyard.com/families/11245.html.

3 Grandpa, David Willard North, had the ill-luck to be the GOP candidate for a safe Republican seat in the Wisconsin House of Representatives in 1912, when the Bull Moose split in the party created a wave of Democratic legislative victories, including one in his district.

4 A more precise set of the current definitions of these segments of the population, taken from a Census publication, follows: “The native population included all U.S. residents who were born in the United States or an outlying area of the United States (e.g., Puerto Rico), or who were born in a foreign country, but who had at least one parent who was an American citizen. All other residents of the United States were classified as foreign-born.” This is from Campbell J. Gibson and Emily Lennon, “Historical Statistics on the Foreign-born Population of the United States: 1950-1990,” U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington D.C., 1999, p. 4, http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/twps0029.html.

5 To be fair to the Census Bureau, it has been asking a question about the second generation in one of its sample studies, but as two highly knowledgeable immigration scholars, Alejandro Portes and Rubén G. Rumbaut, put it: “Since 1994, the annual (March) Current Population Surveys conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau with national samples have asked respondents about the birthplace of their parents, a key question no longer asked in the decennial census. The CPS thus allows estimates of the size and the characteristics of the first and second generations, but the samples are too small to permit reliable analysis beyond a breakdown by a few variables, such as parental nativity, national origin, and year of arrival.” See Alejandro Portes and Rubén G. Rumbaut, Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2001, p. 351.

6 Zehr, op. cit., p. 12.

7 Unfortunately the full set of the Brown University conference papers is not yet available, but will be published in the near future. What is currently available is a website on the conference itself, with a full set of the slide presentations made by the conference speakers. See: http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Education/paradox/.

8 Zehr, op. cit., p. 12.

9 Ibid.

10 The full text of the paper, “Trajectories in Immigrant Student Achievement,” by Dylan Conger of George Washington University, is not currently available, but the slide presentation is. In the latter there was a reference to “roughly 45,000 3rd grade students in 1996,” which may well be the surveyed population. Perhaps the full text of the paper explains why no data were collected on immigrants’ children; perhaps the New York City schools no longer keep records along these lines.

11 The first finding on the slide presentation identified in note 10 was: “Foreign-born 3rd-8th perform better over time than observationally-equivalent native-born peers on citywide reading and math achievement exams.” It is not clear if this means that once ethnic background is held constant that the migrants do better than the natives.

12 The nameless heroes of the story are the construction workers who found the data while rebuilding part of the University; they took the material to a librarian who passed it along to UCLA professors Telles and Ortiz.

13 This led to a book-length report, Edward E. Telles and Vilma Ortiz, Generations of Exclusion: Mexican Americans, Assimilation, and Race, Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 2008.

14 Zehr, op. cit., p. 12.

15 It is not generally recognized that there is only a single federal wage-hour inspector for every 100,000 workers. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which might help the second generation with instances of workplace discrimination, has been similarly weakened in recent years.

16 Telles and Ortiz, op. cit., p. 292.

17 Zehr, op. cit., p. 12.

18 Kathleen Mullan Harris, professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, puts it this way: “A clear and consistent finding in this research was the protective nature of immigrant status. Foreign-born youth experienced more favorable physical and emotional health and less involvement in risky behaviors than native-born youth of foreign-born parents [i.e., the immigrants’ children] and native-born youth of native-born parents.” See her article “Health Status and Risk Behaviors of Adolescents” in Donald J. Hernandez, ed., Children of Immigrants: Health Adjustment and Public Assistance, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 1999, p. 312.

19 Many scholars have made this observation. Carola Suarez-Orazco and Marcelo M. Suarez-Orazco, for example, point out: “In previous eras, well-paid manufacturing jobs allowed blue-collar workers, including immigrants, to achieve secure middle-class lifestyles without much formal education.” We would add immigrants’ children to the sentence. See Suarez-Orazco and Suarez-Orazco, Children of Immigration, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2001, p. 124.