Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

Related: Panel Discussion

Viktor Marsai, Ph.D., is the director of the Budapest-based Migration Research Institute, an associate professor at the University of Public Service, and an Andrássy Fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, DC.

Cooperation with “gatekeeper countries” — transit countries that can help mitigate the flow of irregular migrants — is a key instrument used by Europe to protect its borders, and should be used more consistently by the United States.1

Such collaboration could prevent millions of people from illegally entering destination countries. Without the assistance of those gatekeepers, Europe would have faced a much higher number of illegal immigrants. Therefore, this type of collaboration could be seen as a cornerstone of European migration policy. The United States, on the other hand, pays less attention to gatekeeper states, and focuses on the thin border line as the main protection strategy.

Gatekeeper countries, of course, are only part of the solution, and the concept must be integrated into a much broader and complex immigration and border protection policy that includes physical barriers, human resources, deterrence factors, and a consistent application of existing rules (e.g., detention and deportation). But an effective border regime cannot exist without the cooperation of transit countries.

This paper compares the role of gatekeeper countries in the European and the U.S. contexts. It analyzes the ways different actors are utilizing (or not) transit countries to reduce the number of illegal arrivals. It argues that different historic, economic, and social developments have shaped and altered policies and strategic thinking in the transatlantic region.

* * *

Irregular mass immigration is an obvious challenge on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Nevertheless, the scope of the problem is very different in the United States and the European Union. In FY 2022, the U.S. Border Patrol encountered 2,206,436 people who crossed the Southwest border between ports of entry, a record number.2 In addition, as estimated by various sources, there were 599,000 “got-aways” that year — persons who were detected entering illegally but were not captured by Border Patrol.3Another 172,508 aliens entered through official ports of entry without proper documentation.4

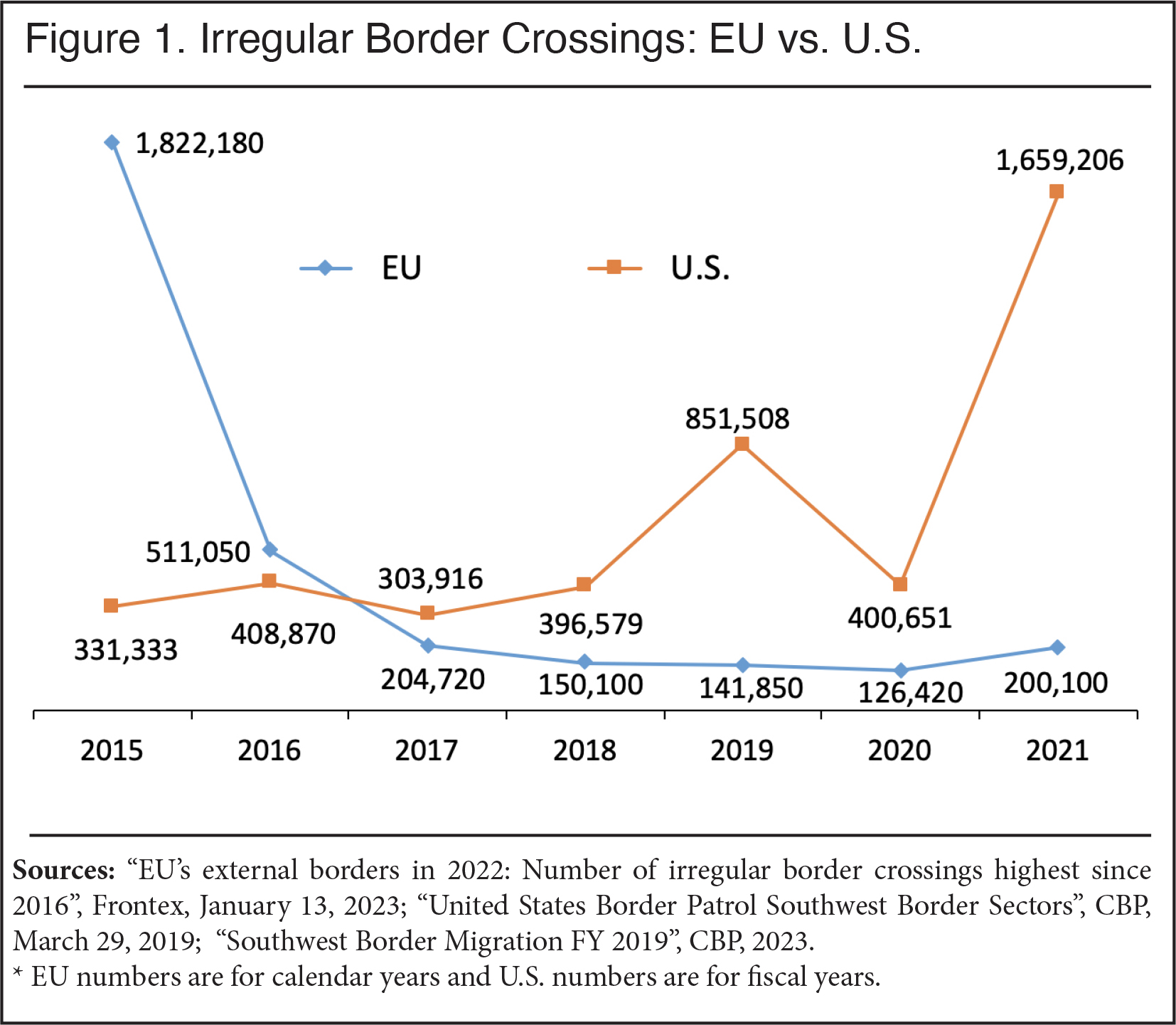

Calendar year 2022 also witnessed a record in Europe, with a 64 percent increase in the number of irregular border crossings (IBCs), totaling more than 330,000 IBCs, the highest figure since 2016. (During the huge irregular influx in 2015, 1,822,180 migrants crossed the external borders of the EU.) Yet, the European numbers were still much lower than the American ones (see Figure 1).

|

Even under the Trump administration, the U.S. government was not able to reduce the annual number of IBCs below 300,000. Europe, on the other hand, with a significantly larger population of almost 450 million people, was successful in mitigating the flow, at least for now. Over the 10-year period from 2013 to 2022, Europe witnessed 3,876,720 IBCs, versus 7,452,267 in the United States. The difference between these two numbers is quite clear, despite the fact that we do not have statistics on got-aways in the EU.

Why such a significant difference? At first sight, Europe has to cope with irregular mass migration under much worse circumstances. The continent has vulnerable borders toward the south and the east, as seen by, for instance, the use of boats to cross the Mediterranean. Furthermore, dangerous but accessible sea borders make it almost impossible to stop migrants who try to reach the southern shores of the continent. The geostrategic setting also worsened a lot in the past decade: The so-called Arab Spring destabilized regimes from Libya to Syria; civil wars broke out from Ethiopia to Sudan; the financial and economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic; and the Russian invasion of Ukraine has jeopardized living conditions and prospects in the Middle East, North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa, encouraging people to leave for Europe.5 Jihadist insurgency in the Sahel also stoked tension and forced millions of people to flee.6

In addition, consensus on immigration policy is lacking in Europe. The debate in the European Council on possible actions regarding border protection in March 2023 demonstrated that many member states wanted stronger measures, while others argued against a “fortress of Europe” approach — even if this meant more IBCs.7 The stalemate around the proposal of the European Commission on the new European pact on migration and asylum points even more to the division and disagreement among European capitals.8

Yet despite these challenges and differences, the number of illegal arrivals is much lower in Europe than in the United States. How can this be explained? If it is not the internal migration policy of the EU or an improving geopolitical environment, there must be other instruments that are keeping these numbers down on the eastern side of the Atlantic.

One of them is the collaboration of the EU Commission and member states with “gatekeeper countries” around Europe, from Turkey and Egypt to Niger and Morocco. The cooperation with transit countries to mitigate the flow of irregular migrants is a key instrument in the hand of Europe to protect its borders.

On the other hand, the United States pays less attention to gatekeeper states, and looks at its porous border as the first line of protection. The different policy appraisals between the U.S. and the EU were highlighted by Mark Krikorian when he observed that “in the U.S. discussion of this we need to stop thinking of the Border Patrol agent as the first resort in stopping illegal immigration and rather think of him or her as the last resort.”9

The concept of the gatekeeper country is more of a political and foreign policy practice than a matured theory. This paper will first offer a conceptual and theoretical framework to define the place of gatekeeper countries in the general framework of migration studies and the ongoing discussion in the field. Then, it will analyze practical considerations, namely how destination countries’ collaboration with gatekeeper countries can serve as a useful tool against irregular mass migration. Lastly, it will examine the implementation of the concept both in Europe and the United States.

This research is not exhaustive; further investigation is needed for better understanding of why the United States seems sometimes reluctant to collaborate with transit countries to reduce illegal immigration, and to address more specifically the perspectives of gatekeeper countries in Central America.

Gatekeeper Countries — a Conceptual Framework

Cooperation with gatekeeper countries to mitigate the flow of irregular migration is not a new phenomenon; EU governing bodies and certain member states have been collaborating with transit states for decades. Nevertheless, in academic literature the concept of gatekeeper countries is a poorly developed theory. Hence, there is a need to set up a theoretical framework up front.

To avoid any confusion, it is important to define what this gatekeeper concept is not about. It has nothing to do with the theory of gatekeeper states in Africa, developed by Frederick Cooper in the early 2000s.10 In his book, Cooper described African states as gatekeepers that are trying to balance unstable domestic politics against the influence of external factors, with varying success. Cooper’s term does not relate to immigration, and is used more as a concept for political science.

Another example of what this concept is not about is Operation Gatekeeper. That was a Clinton administration initiative launched by the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1994 to reduce the number of illegal border crossings in the San Diego border sector.11 In this context, the U.S. Border Patrol’s agents were themselves the gatekeepers, whereas the gatekeeper concept in this paper pertains always to transit countries serving as gatekeepers.

That is why a recent paper by Ðana Luša is also not part of this gatekeeper theory.12 Although Luša is using the term “gatekeepers”, she refers to small EU member states — Greece, Croatia, Bulgaria, and Hungary — as gatekeepers, which is close to the concept of Operation Gatekeeper in the U.S. In addition, Luša also confuses the reader in the theoretical part of her paper by discussing the topic in the framework of externalization of EU policies.13 That is conceptually wrong, since as EU member states they are part of Europe, so they cannot be part of externalization.

To get closer to the definition of gatekeeper countries, we should distinguish between three approaches. The first is the geographic one. In general, migration studies and discourse separate three geographic areas: the countries of origin, transit countries, and destination countries. Gatekeeper countries are generally transit countries, even if — as I will examine below — they can work as countries of origin as well.

The second is a thematic approach. The concept of gatekeeper countries is part of immigration critic/realist theory. It means that gatekeeper countries are part of the toolkit to stop illegal immigrants on their way to destination countries. It is true for all kinds of irregular migration: Whether persons leave their home because of persecution and war or just because they seek greener pastures (economic migrants), gatekeeper states serve as an obstacle on their route toward destination countries, regardless of whether they were provided with shelter and proper asylum procedures.

Gatekeeper countries are part of the discussion on externalization of immigration and asylum procedures as well; therefore, the collaboration with them can be considered as outsourcing of the aforementioned processes.14 Furthermore, some authors argue that “the construction of the externalized European borders represents a new form of coloniality, classifying the population (migrant vs. EU citizen) and the countries (EU members vs. countries where control has been externalized to) according to the level of threat they represent for the EU.”15 So, in mainstream academic literature on immigration studies, externalization is seen as a negative phenomenon, unless it is used not to reduce the number of arrivals but to increase it. For example, the expansion of geographic availability of asylum procedures in the developed world and the establishment of processing centers in third countries are considered positive moves.16

Another thematic approach has to do with the securitization of immigration. Some have accused policymakers of viewing immigration crises as security threats, jeopardizing the humanitarian aspect of the phenomenon and the access of immigrants to proper protection of their fundamental human rights. According to them, border protection, the concept of “fortress Europe”, and efforts to reduce the arrival numbers are against the fundamental rights of immigrants.17 In short, they view securitization as demonizing immigrants.18

Away from these normative stands, the concept of gatekeepers brings in a practical aspect without falling into ethically “bad” or “good” positioning. It reinforces the fact that securitization and externalization are already part of immigration policy, if only because security challenges and threats are an unavoidable aspect of any immigration crisis. Therefore, they have a relevant space — among other issues — in academic discussions on immigration, as well as gatekeeper states.

The third point, linked to the one above, is that independently of the academic discourse, the practice of cooperation with gatekeeper countries has already been part of immigration policies on both sides of the Atlantic. The practices are there, and so researchers and experts have to understand the nature of collaboration with gatekeeper countries, analyze its complexity, and measure its effectiveness, while avoiding normative statements.

To summarize, gatekeeper countries are entities which:

- Are located on transit routes toward destination countries/regions;

- Are relatively close — geographically speaking — to destination countries/regions, though in some other cases — like EU collaboration with Niger — they are more distant;

- Have the capacity and intent to mitigate the flow of illegal mass immigration (e.g., they have functioning governing/ruling powers, which does not necessarily mean that they have a strong central government, as Libya, for instance, does not);

- Can be also countries of origin — but this is less common, because the primary task of a gatekeeper is to help stop outsiders from crossing their territory on their way to destination countries.

Following this logic, for Europe, typical gatekeeper states are Turkey, Morocco, Niger, Libya, or Serbia. In the case of the United States, the gatekeepers could be Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, and The Bahamas.

Practical Considerations Regarding Gatekeeper States

To understand why the use of gatekeeper countries is considered an essential practice when it comes to Europe and, to a much lesser extent, the U.S., we have to analyze its strengths, advantages, and drawbacks.

First, European history teaches us that a single fence — even if it is a heavily fortified one like the Roman Limes — can hardly stop the flow of masses of people who want to cross to the other side. The 2015 migration crisis was a major example of that: Although physical barriers were somewhat effective in slowing the flow of people, they could not stop millions of irregular migrants from reaching their destination. In addition, most of the external borders of the EU Schengen Zone are at sea, where it is impossible to erect fences.

Furthermore, both the EU and the U.S. know from experience that voluntary repatriation, deportation, and other forms of expulsion of unlawful immigrants are extremely difficult. In the case of the EU, for instance, the return rate of migrants is just 21 percent.19 ICE in FY 2022 deported only 72,177 persons from the United States, which, when compared to the 2.2 million IBCs, is very limited.20 This is why it is easier to stop irregular migrants before they reach the territory of the EU and the U.S. and why, for instance, Europe has developed structural and complex lines of border protection — that do not start on its immediate borders.

That said, outsourcing asylum and migration processes does not come without concerns, such as the above-mentioned human right issues and accusations of neo-colonization. Nevertheless, it also provides benefits: Asylum procedures are much cheaper in a developing country than in a developed one, if only because the cost of living is much lower. This means that with the same amount of money many more people can be taken care of. Two UK agreements, with Rwanda and France, respectively, are perfect examples of such practical considerations. Under the deal between London and Kigali, Rwanda would be ready to accept asylum seekers deported from the UK. In compensation, Rwanda would get £140 million ($175 million). Knowing that the UK’s asylum system costs £1.5 billion ($1.88 billion) a year and Great Britain spends £7 million ($8.75 million) daily for hotel accommodations for asylum seekers, the UK’s decision makes a lot of sense. But the implementation of this agreement has been suspended following the European Court of Human Rights’ decision concerning the legality of such a deal.21 Meanwhile, as it waits for a legal outcome, the UK made a deal with the French government that will allow for the readmission of illegal immigrants to France and the strengthening of border protection between the two countries. As compensation, the UK paid France £465 million ($581 million).22

Cooperation with gatekeeper countries can also enhance the power of deterrence. Persons who simply seek better economic circumstances would think twice about investing thousands of dollars — thus financing organized criminal networks — for a journey if there is a good chance that they would to be stopped at one of the transit countries. This is an important part of dissuading people from risking their lives in a perilous journey. At the same time, it would deter economic opportunists — who overburden the asylum and refugee systems — from making the move, while giving victims of forced displacement a better chance of being assisted.

Because of their geographic proximity to sending countries, gatekeeper states offer a better chance for the return of immigrants. For those not returned, gatekeepers often allow for easier integration of migrants because of familiar cultural, social, and historical characteristics. If we look at the case of Syrian refugees in Turkey, for instance, we note that more than half (58.6 percent) do not want to move to a third country (meaning that they do not want to move on to Europe), and 30.3 percent are ready to return to Syria should a comprehensive peace agreement take place. The 2020 Syrian Barometer in Turkey shows that most Syrian refugees were satisfied in the country, and integrated very well into society.23

It is worth noting that migrants who have been integrated into a developed society like Europe or the U.S., and have thus already established their existence far from their home, have a limited chance and desire to return to their developing country, even when peace is attained. This integration deprives third-world countries of important human capital, and actually works as a brain-drain.

Another advantage of collaboration with gatekeeper countries is that it offers a wide toolkit. It takes place between states, which means that its implementation is smoother than it would be with different actors (NGOs, multinational companies, advocacy groups, etc.). Cooperating governments have many different instruments to settle and maintain any agreement. Even though some might view this type of collaboration as involving only elements of immigration policy (“immigrants for immigrants” deals), that is definitely not the case. Diplomacy, trade, development assistance, humanitarian aid, security and defense collaboration, etc., can also be part of any such deal. This is obvious in the EU-Turkey Statement of 2016, wherein Brussels offered not only assistance on asylum issues for Ankara, but also promised to “re-energize the accession process” of Turkey to the EU.24 Similarly, the Trump administration threatened to suspend the trade agreement with Mexico if it did not help combat illegal immigration.25

As with any other form of international cooperation, migration deals include numerous challenges. Mutual bargaining and blackmailing are always part of the game. To minimize these risks, two different approaches can be undertaken. One is a “carrot and stick” policy, whereas the other is the “win-win” approach. Both have advantages and disadvantages so it is, therefore, hard to choose and implement only one of them.

Carrot and Stick. Principally, the carrot-and-stick approach is used if the gatekeeper state does not want to cooperate and stop illegal immigration. Therefore, the destination country has to pressure the gatekeeper to convince it to collaborate. In most cases, there is also a “carrot” in the arrangement to provide some benefits for the gatekeeper. One typical example of a carrot-and-stick agreement is the Migration Protection Protocols (MPP, also known as Remain in Mexico), in which foreign individuals entering or seeking admission to the U.S. from Mexico — illegally or without proper documentation — could be returned to Mexico and wait there for the duration of their proceedings.26

Another example is the EU pressure on Serbia. Numbers from the EU border agency, Frontex, show that 19,160 people were detected illegally travelling to the EU through the Western Balkans in September 2022 alone. Reacting to these numbers, Nancy Faeser, Germany’s interior minister, said “Serbia has to adapt its visa practice to the EU if it wants to become an accession candidate.”27 This led to Brussels demanding that Belgrade suspend visa-free arrangements (visa waivers) for travelers from certain countries (Tunisia, India, and Burundi) who otherwise could get direct access to a neighboring country of the Schengen zone.

Of course, the carrot-and-stick policy has its weaknesses. Because it is an enforced bargain, in most cases it only works when the conditions are favorable. For instance, after the election of Joe Biden, Mexico was less willing to cooperate with the United States as a gatekeeper. As Todd Bensman has highlighted, on November 11, 2020 — within eight days of Biden’s election — a law entitled “Various Articles of the Migration Law and the Law on Refugees are Reformed, Complementary Protection and Political Asylum in the Matter of Migrant Children” was signed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. The law prohibited federal detentions of migrant families with minor children in Mexican detention facilities. That meant that Mexico could start emptying its detention centers, and thousands of families with their young children could travel freely inside the country — and out, mainly toward the U.S.28

Therefore, a carrot-and-stick policy can be fragile and, of course, it is a tool not only in the hands of the destination country, but also in the hand of the gatekeeper as an instrument for bargaining and blackmailing. One example is when Morocco let 6,000 illegal immigrants mainly from Sub-Saharan Africa storm the border fence on the Spanish enclave Ceuta in 2021. This move came after Madrid allowed Sahrawi leader Brahim Ghali — who led the Polisario Front’s fighting for Western Saharan independence from Rabat — to be treated in a Spanish hospital.29

Win-Win. There can be a win-win approach for both destination countries and gatekeepers as well, when cooperation offers equal benefits for all parties involved. For instance, in a trilateral agreement, Austria and Hungary offered assistance to Serbia to protect its southern border with North Macedonia. The aim of the cooperation was to prevent irregular migrants from entering Serbia and turning it into a “parking lot” for migrants trying to reach the EU, as Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić said.30 The U.S. launched similar efforts in the form of the Southern Border Plan aiming to construct a network of communications towers along Mexico’s southern border region in 2014-15 to help security and immigration officers there communicate despite gaps in radio coverage.31

In spite of its advantages, the win-win approach has also its challenges. First, similarly to a carrot-and-stick deal, it can be fragile. Shifting trends can jeopardize it, even if to a lesser extent than in the case of a carrot-and-stick agreement, if only because the parties are much more interested in the success of the deal. Second, this framework cannot solve every problem. For instance, in the Serbian example, North Macedonia would become the “parking lot” instead of its northern neighbor, so the trilateral agreement did not solve the original problem, just moved it to another border line. Therefore, the possibility of a win-win solution is geographically limited.

Gatekeepers in Practice – the European Experience

As mentioned previously, the use of gatekeeper countries in the struggle against irregular mass migration to Europe is not a new instrument; it was part of various migration-related agreements in past decades. It can be seen as a long historical tradition in Europe: Over the last 20 centuries, invasions and attacks regularly arrived from the peripheries of Europe (by Germans, Huns, Arabs, Vikings, Hungarians, Mongols, Ottomans, Russians, et al.). This meant that European power centers had to always pay attention to the world beyond the continent. Paradoxically, colonization — when Europe itself became the invader — just strengthened this notion. Europe could not, and cannot (despite the decolonization), ignore events happening around the world because of political, security, and economic considerations. Therefore, cooperation with gatekeepers has become an integral part of strategic thinking in Europe, not only against irregular immigration, but also against other threats and challenges, like political instability, terrorism, or drug-trafficking. This was evident, for instance, in the form of the pre-Arab Spring collaboration with authoritarian regimes in North Africa, which served as a cordon sanitaire for the EU before 2011.32

Establishing a legal framework for gatekeeper collaborations started in the early 1990s. For instance, in 1992, Morocco and Spain signed a readmission deal, in which they agreed to the following: “at the formal request of the border authorities of the requesting State, border authorities of the requested State shall readmit in its territory the third-country nationals who have illegally entered the territory of the requesting State from the requested State.”33 Many other agreements followed the deal between Rabat and Madrid. In 2003, Mauritania and Spain signed a readmission agreement to allow the repatriation of those arriving at Spain’s Canary Islands illegally. Spain also entered a cooperation agreement with Mauritania, providing equipment and training to Mauritanian border control forces.34 In 2006, Spain and Senegal agreed to jointly patrol Senegalese territorial waters to help mitigate the wave of illegal migration to the Canary Islands.35 Italy and Libya signed an agreement in 2008 under which Italy promised to pay $5 billion in compensation for colonial misdeeds and to gain certain economic and political benefits. As the part of the deal, Italy not only expected to win energy contracts but also wanted Tripoli to toughen security measures and stem the flow of illegal immigration.36

The current migration crisis, which started with an increase in the number of crossings in the Central Mediterranean route toward Italy in 2013 and reached a peak with the arrival of Syrians in 2015, gave new impetus to the process. The EU turned to certain neighboring countries to design gatekeeper agreements with them or strengthen existing ones. While the most famous was the EU-Turkey Statement, the EU and the member states made other gatekeeper deals with Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, and with certain Western Balkan states.37

The Success of EU Gatekeeper Deals. Although these types of agreements were criticized by a number of scholars and NGOs, they were successful at reaching their primary goal, namely to reduce the number of irregular border crossings.38 The figures are impressive. Turkey hosts at least 3.6 million registered Syrian refugees and some 320,000 refugees of other nationalities. Under the framework of the EU-Turkey Statement, Ankara is supposed to stop them from moving on to the EU.39

The deal is a success. While 885,386 migrants made it to the EU via the Eastern Mediterranean route — mostly through and from Turkey — in 2015 (17 times the number of 2014, which was itself a record year at the time), IBCs dropped to 182,227 in 2016 and 42,319 in 2017.40 Brussels mobilized €9.5 billion ($10.3 billion) toward Turkey and the refugees it hosts since 2015. As large as it is, this monetary contribution is low compared to the potential cost of hosting hundreds of thousands of people in the EU.

Egypt is another important gatekeeper on the southern shore of the Mediterranean. It hosted nine million migrants and refugees in 202241 — three million more than in 2021.42 This increase is due to the global food crisis and civil wars in Sudan and Ethiopia. Nevertheless, Cairo proved to be a committed partner in the EU-Egypt Political Dialogue on Migration against irregular migration.43 Since 2016, when a boat carrying irregular migrants capsized along the Egyptian coast and hundreds of people died, Cairo has closed its shores to irregular departures; very few — if any — boats have left Egyptian coastlines since.44

On a smaller scale, three other North African gatekeeper states — Libya, Tunisia, and Morocco — have also made significant efforts to stop illegal crossings. (Few migrants try to transit Algeria.) In the first nine months of 2022, Rabat prevented 40,000 IBCs heading to Europe by sea and 7,000 by land.45 Between January and October 2021, the EU-trained and -equipped Libyan Coast Guard intercepted 30,000 people on their way toward Italy46 — there were 680,000 immigrants in Libya in the middle of 2022.47 Although not all of them want to leave North Africa, it is still a huge number that is well represented by the fact that 106,000 illegal migrants reached Italy by sea from Libya and Tunisia in 2022.48 Between 2020 and 2022, Tunisian authorities prevented more than 76,600 IBCs as well.49

It is also important to highlight here the role of Niger, which does not seem like a typical gatekeeper since it is located far from the EU. The country — which is one of the most important transit routes toward Libya — plays a decisive role as a partner for Europe. In December 2016, Brussels offered €610 million in support for Niger to reduce the number of irregular migrants crossing the Sahel.50 After the agreement, the number of people using Niger as a transit route toward the Mediterranean sharply declined; while it is estimated that more than 300,000 migrants crossed through the country in 2016, this number fell to 60,000 in the first seven months of 2017 — a 60 percent decrease.51

To sum up, hundreds of thousands of irregular immigrants, at least, are being stopped by the Middle East and North African gatekeeper countries annually.

What About the U.S. and Its Gatekeepers?

On the U.S. front, the Southern Border Plan and the MPP collaboration could be considered gatekeeper strategies, so this is not a new practice. Nevertheless, cooperation with transit countries is still far from being an integral part of U.S. immigration policy, as it is for the EU.

This is true for different reasons. First, the illegal immigration crisis in the United States is a relatively new phenomenon (starting in earnest in the early 1970s), and there is no consensus among the various political, academic, and civic entities in the United States as to whether it is a problem or a solution.52 For instance, the current Biden administration is still avoiding the word “crisis” when faced with the record number of encounters in the Southwest border.53 In a way, for them, if there is no crisis, no solution is needed.

Second, strategic thinking in the United States is quite different from Europe. Compared to Europe’s long experience of unwanted migration from beyond its borders, America’s geographical isolation means that an “Ocean Shield” mentality is still strong. In the past, the U.S. was not pressed to establish extended and complex collaboration with its close neighbors because their impact on America was limited, except for trade relations and the common fight against drug trafficking. This explains why Washington paid less attention to countries in Central and South America than, for example, to those in the Middle East or East Asia.

The historically hegemonic position of the U.S. is also an obstacle for better understanding — and handling — of the immigration crisis. It is not evident that the biggest economic and military power of our globe is unable to defend its own borders and needs the support of much smaller states to do so. Nevertheless, in the age of mass illegal migration, border protection starts next door, and it is almost impossible to successfully protect a porous border line stretching for hundreds or thousands of miles.54

In recent years, the U.S. finally acknowledged the need to collaborate with other countries on immigration. That said, policies and approaches varied from one administration to another. The Trump administration, for instance, undertook draconian measures to reduce the number of IBCs. On the other hand, the Biden administration has used a much softer approach, as shown in the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection;55 instead of stopping illegal flows it has sought to channel them through legal (or “legal”) pathways created for that purpose (e.g., temporary parole measures).56 The confusing messages from different administrations convinced gatekeeper countries to soften their immigration policies and let more migrants toward the U.S. when the “stick” was not so active. Therefore, if the United States does not develop a long-standing and sustainable policy on illegal immigration that is independent of the occupant of the White House, it will be hard to convince potential gatekeepers to help stop the flow of people.

Conclusion

Collaboration with gatekeepers is not without risks, nor is it a silver bullet. Using countries as gatekeepers is only part of a comprehensive solution to mass illegal migration. The concept must be integrated into a much broader and complex immigration policy that includes physical barriers, human resources, deterrence factors, and the systematic application of the law (e.g., detention and expulsion). But it is evident that effective border defense is hard to imagine without the cooperation of transit countries. EU countries’ successful collaboration with gatekeepers underlines the potential of such measures. Gatekeeper countries can reduce the number of IBCs by hundreds of thousands annually, while hosting millions of potential migrants at a relatively modest cost. U.S. policymakers should consider this approach, and recognize that border fences and patrols are not the first line of protection, but should be the last.

End Notes

1 The terms “EU” and “Europe” are used interchangeably here.

2 “Southwest Land Border Encounters”, CBP, 2023, downloaded April 28, 2023.

3 Letter of the Committee of the Judiciary to the Honorable Alejandro Mayorkas, Secretary U.S. Department of Homeland Security, October 19, 2022, downloaded April 28, 2023.

4 “Southwest Land Border Encounters”, CBP, 2023, downloaded April 28, 2023.

5 Matt Herbert, “Losing hope. Why Tunisians are leading the surge in irregular migration to Europe?”, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, January 2022, downloaded May 1, 2023.

6 “Sahel and Somalia Drive Rise in Africa’s Militant Islamist Group Violence”, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 9, 2022, downloaded May 1, 2023.

7 Viktor Marsai, “Is Symbolism More Important than Pragmatism in Europe’s Border Control?”, The National Interest, March 7, 2023, downloaded, May 1, 2023.

8 “New Pact on Migration and Asylum”, European Commission, September 20, 2020, downloaded May 1, 2023.

9 “Panel Transcript: Gatekeeper Countries”, Center for Immigration Studies, April 28, 2023, downloaded May 1, 2023.

10 Frederick Cooper, Africa since 1940: The past of the present, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

11 Jose Palafox, introduction to “Gatekeeper’s State: Immigration and Boundary Policing in an Era of Globalization”, Social Justice, Vol. 28, No. 2 (2001) 1-6., p 3.

12 Ðana Luša, “Small States: ‘The Gatekeepers’ of EU Borders During the Migration Crisis”, in Tómas Joensen and Ian Taylor (Eds.), Small States and the European Migrant Crisis, Cham: Palgrave–Macmillen, 2015-241, 2021.

13 Luša 2021, p 219.

14 Luša 2021, p 221.; Hafsa Afailal and Maria Fernandez, “The Externalization of European Borders: The Other Face of Coloniality Turkey as a Case Study”, Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, 215-223, 2018.

15 Afailal–Fernandez 2018, p. 215.

16 Pauline Endres de Oliveira and Nikolas Feith Tan, (2023). “External Processing A Tool to Expand Protection or Further Restrict Territorial Asylum?”, MPI, February 2023, downloaded May 11, 2023.

17 Afailal–Fernandez 2018, p. 220.

18 Thomas Spijkerboer, “The Global Mobility Infrastructure: Reconceptualising the Externalisation of Migration Control”, European Journal of Migration and Law 20 (2018) 452–469, 2018, p. 453.

19 “Return and readmission”, EU Migration and Home Affairs, 2023, downloaded May 11, 2023.

20 “ICE immigration arrests and deportations in the U.S. interior increased in fiscal year 2022”, CBS News, December 30, 2022, downloaded May 11, 2023.

21 “What is the UK’s plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda?”, BBC May 3, 2023, downloaded May 12, 2023.

22 “UK to fund France detention site as leaders agree migration deal”, Al-Jazeera, March 10, 2023, downloaded May 12, 2023.

23 M. Murat Erdoğan, “Syrians Barometer 2019. A Framework For Achieving Social Cohesion With Syrians In Turkey”, Orion Kitabevi, 2020, p. 176, downloaded May 12, 2023.

24 “EU-Turkey statement”, Consilium.europa.eu, March 18, 2016, downloaded May 12, 2023.

25 “Trump threatens more tariffs on Mexico over part of immigration deal”, Reuters, June 10, 2019, downloaded May 12, 2023.

26 “Migrant Protection Protocols”, DHS, January 24, 2019. Downloaded May 15, 2023.

27 “Serbia Has Introduced Visas to Citizens of Several Countries in 2022 Due to EU Pressure”, Schengenvisainfo, December 29, 2022, downloaded May 12, 2023.

28 “How Mexico outfoxed Joe Biden on illegal immigration, knowing he’d never fight back”, Center for Immigration Studies, March 10, 2023, downloaded May 15, 2023.

29 “Migrants reach Spain’s Ceuta enclave in record numbers”, BBC, May 18, 2021, downloaded May 15, 2023.

30 Viktor Marsai, “In the Age of Illegal Mass Migration, Border Protection Starts Next Door”, The National Interest, April 26, 2023, downloaded May 15, 2023.

31 Maureen Meyer and Adam Isacson, “The ‘Wall’ Before the Wall: Mexico’s Crackdown on Migration at its Southern Border”, Wola, December 17, 2019, downloaded May 15, 2023.

32 Mason Richey, “The North African Revolutions: A Chance to Rethink European Externalization of the Handling of Non-EU Migrant Inflows”, Foreign Policy Analysis Vol. 9, No. 4 (October 2013), pp. 409-431.

33 “Agreement Between the Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of Morocco on the Movement of People, the Transit and the Readmission of Foreigners Who Have Entered Illegally”, February 13, 1992, downloaded May 1, 2023.

34 “Spain and Morocco Failure to protect the rights of migrants – Ceuta and Melilla one year on”, Amnesty International, October 2006, p 3, downloaded May 1, 2023.

35 “Senegal, Spain agree to joint patrols to stem illegal migration”, The New Humanitarian, August 25, 2006, downloaded May 1, 2023.

36 “Gaddafi and Berlusconi sign accord worth billions”, Reuters, August 30, 2008, downloaded May 1, 2023.

37 Bachirou Ayouba Tinni, Olga Djurovic, et al., “Asylum for Containment. EU arrangements with Niger, Serbia, Tunisia and Turkey”, Asile, March 2023, downloaded May 15, 2023.

38 Ibid.; Afailal-Fernandez 2018.

39 “Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Turkey”, UNHCR, 2023, downloaded May 16, 2023.

40 “Frontex – Eastern Mediterranean Route”, Frontex, 2023, downloaded May 16, 2023.

41 “Egypt received 9 M refugees over past years: Chief of committee for combating and preventing illegal migration”, Egypt Today, December 11, 2023, downloaded May 16, 2023.

42 “Egypt proud of hosting 6 M of immigrants, refugees: Foreign Ministry Spox”, Egypt Today, December 18, 2021, downloaded May 16, 2023.

43 “Joint Press Statement: The third EU – Egypt Political Dialogue on Migration”, EUNeighbours.eu, November 21, 2021, downloaded May 16, 2023.

44 “Egypt as a Country of Origin”, EUAA, July, 2022, downloaded May 16, 2023.

45 “Marruecos se mantiene firme en su compromiso de frenar la inmigración ilegal hacia Europa”, Atalayar, September 20, 2022, downloaded May 16, 2023.

46 “Libyan coastguard intercepts 500 migrants in latest clampdown”, October 3, 2021, downloaded May 16, 2023.

47 “Migration flows on the Central Mediterranean route”, Consilium.europa.eu, 2023, downloaded May 16, 2023.

48 “Italy estimates 680K migrants in Libya want to cross Mediterranean Sea for Europe”, Fox News, March 13, 2023, downloaded May 16, 2023.

49 Hamza Meddeb, “Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe”, Carnegie, March 20, 2023, downloaded May 16, 2023.

50 “EU offers 610 million euros to Niger to curb migration”, Reuters, December 16, 2016, downloaded May 16, 2023.

51 “Niger smugglers take migrants on deadlier Saharan routes: U.N.”, Reuters, August 18, 2017, downloaded May 16, 2023.

52 Adam Isacson, “The U.S. Government’s 2018 Border Data Clearly Shows Why the Trump Administration is on the Wrong Track”, Wolo, November 9, 2018, downloaded May 17, 2023.

53 “There’s an Immigration Crisis, But It’s Not the One You Think”, Politico, March 25, 2021, downloaded May 17, 2023.

54 Viktor Marsai, “In the Age of Illegal Mass Migration, Border Protection Starts Next Door”, The National Interest, April 26, 2023, downloaded May 15, 2023.

55 “Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection”, USAID, 2022, downloaded May 17, 2023.

56 Andrew Arthur, “DHS Giving Illegal Migrants Up to One Year to Settle in on ‘Parole’”, Center for Immigration Studies, May 24, 2022, downloaded May 17, 2023. See also, Andrew Arthur, “What’s Biden Doing with Migrants at the Ports of Entry?”, Center for Immigration Studies, May 30, 2023, downloaded May 30, 2023.