Fueled in part by enormous and, in this century, unprecedented numbers of new immigrants, the United States is becoming dramatically more diverse ‹ racially, ethnically, and culturally. The latest census figures show that the number of legal and illegal immigrants living in the United States has almost tripled since 1970, rising from 9.6 million to 26.3 million today and far outpacing the growth of the native-born population.1 Moreover, a substantial percentage of these immigrants arrive here from countries with very different cultural and political traditions at a time when American cultural values are increasingly questioned by some.2 A critically important question, therefore, is whether the unprecedented diversity brought about by recent immigration is being achieved at the expense of a common national culture.

It is within this context that questions about the impact and advisability of allowing or encouraging dual or multiple citizenships arise.3 The consequences of allowing or encouraging the acquisition of multiple citizenships by immigrants and citizens in the United States have rarely come up outside of a small group of law school professors and post-modern theorists, but they deserve to be discussed. This narrow group has generally endorsed the desirability of allowing new immigrants and American citizens to pursue their associations with their "countries of origin." Some go farther and advocate the acquisition and consolidation of active attachments to other countries as a means of overcoming what they view as the parochialism of American national identity.

Yet, the basis for either endorsing or advocating the development of multiple national attachments is ordinarily based on narrow legal analysis wherein anything permitted is acceptable, or on the "post-modern" advocate's highly abstract theoretical musings, wherein anything permitted is suitable. The psychological implications and political consequences of having large groups of Americans holding multiple citizenships are rarely, if ever, seriously considered. Yet, such questions go to the very heart of what it means to be an American and a citizen. They also hold enormous implications for the integrity of American civic and cultural traditions. Is it possible to be a fully engaged and knowledgeable citizen of several countries? Is it possible to follow two or more very different cultural traditions? Is it possible to have two, possibly conflicting, core identifications and attachments? Assuming such things are possible, are they desirable?

Before we can address these questions, several others must be considered. First, how many countries allow their nationals to have multiple citizenships? Solid numbers are in short supply. In a 1996 paper, Jorge Vargas put the number at 40.4 One year later, a 1997 draft memorandum on dual citizenship prepared for the United States Commission on Immigration Reform said that "at least 37 and possibly as many as 47 countries allow their nationals to possess dual nationality."5 Eugene Goldstein's list of countries allowing multiple citizenships (published in 1998) put the number at 55.6 The small number of others who have written on multiple citizenships mostly seem content to list a few multiple-citizenship-allowing countries, apparently believing that the actual number of such countries has no bearing on their analyses, implications, or others' responses to this phenomenon.

How many Americans are eligible for, or claim, multiple citizenship status? We don't know. As The Wall Street Journal puts it, "no one knows just how many citizens claim a second nationality,"7 or are entitled to do so. Why? According to Peter Spiro, an enthusiastic advocate of multiple citizenships, "Statistical surveys of the number of dual nationals appear never to have been undertaken, nor have the United States or other governments sought to collect such information."8 Yet, he estimates that Mexico alone, which recently passed a law allowing its nationals dual-citizenship rights, could create in the United States, "almost overnight a concentrated dual-national population numbering in the millions." How many millions? He doesn't say.

According to T. Alexander Aleinikoff, another advocate of multiple citizenships, "The U.S. Government does not record, and has not estimated, the number of U.S. dual citizens, but the total may be quite large."9 How large? He doesn't say.

The purpose of this Backgrounder is to provide some numerical specificity to vague or otherwise non-existent estimates of the number of persons in the United States who are eligible for dual or multiple citizenship status. Numbers alone, of course, do not necessarily confer political or cultural significance. Neither, however, are they irrelevant to them. Vast numbers of citizens eligible for multiple citizenships are surely of more concern than small numbers.

I first briefly discuss the concept of multiple citizenships. I then turn to an enumeration of those countries that allow it and examine them in the context of American immigration policy in recent years. These numbers lead to the subtitle of this study: "An Issue of Vast Proportions and Broad Significance."

What Is Dual Citizenship?

At it most basic level, dual or multiple citizenship involves the simultaneous holding of more than one citizenship or nationality. That is, a person can have each, or many, of the rights and responsibilities that adhere to a citizen in all of the several countries in which he or she is a citizen, regardless of length of time or actual residence in a country, geographical proximity, or the nature of his or her economic, cultural, or political ties.10

The idea seems on its face counterintuitive. How could a person owe allegiance or fully adhere to the responsibilities of citizenship in several countries at the same time? In the United States, the legal answer is: easily.

The United States does not formally recognize dual citizenship, but neither does it take any stand - politically or legally — against it. No American citizen can lose his or her citizenship by undertaking the responsibilities of citizenship in one or more other countries. This is true even if those responsibilities include obtaining a second or even a third citizenship, swearing allegiance to a foreign state, voting in another country's election, serving in the armed forces (even in combat positions, and even if the state is a "hostile" one), running for office, and if successful, serving.11 Informed constitutional judgment suggests Congress could legislatively address any of these or other issues arising out of these multiple, perhaps conflicting, responsibilities.12 Yet, to date, it has chosen not to do so.

A person in the United States may acquire multiple citizenships in any one of four ways.13 First, he or she may be born in the United States to immigrant parents: All children born in the United States are U.S. citizens regardless of the status of their parents (jus soli). Second, a person may be born outside the United States to one parent who is a U.S. citizen and another who is not. A child born to an American citizen and British citizen in the United Kingdom, for example, would be a citizen of both countries. Third, a person becomes a naturalized citizen in the United States and that act is ignored by his or her country of origin.14 This is true even if the country of naturalization requires, as the United States does, those naturalizing to "renounce" former citizenship/nationality ties. In the case of the United States, failure to take action consistent with the renunciation carries no penalties, and others countries can, and usually do, ignore that oath of allegiance. Fourth, a person can become a naturalized citizen of the United States and in doing so lose her citizenship in her country of origin, but can regain it at any time, and still retain her U.S. citizenship.15

Dual or multiple citizenship is not the same as dual nationality. Citizenship is a political term. It draws its importance from political, economic, and social rights and obligations that adhere to a person by virtue of having been born into, or having become a recognized or certified member of, a state.

Nationality, on the other hand, refers primarily to the attachments16 of members of a community to each other and to that community's ways of viewing the world, practices, institutions, and allegiances. Common community identifications develop through several or more of the following elements: language, "racial" identifications, ethnicity, religion, culture, geography, historical experience, and identification with common institutions and practices.

In many culturally homogenous countries nationality and citizenship coincide, yet they are not synonymous. Or, as Peter Schuck argues, "an individual's national identity is not necessarily the same as the passport she holds."17 This, of course, is precisely the problem, but a detailed analysis of those issues must await another time and place.18

Countries Allowing Dual Citizenship: A Large and Fast-Growing Group

Conduct a small experiment. Ask your friends and colleagues how many countries world-wide permit their citizens to also be citizens of one or more other countries. Frame the question by asking whether it might be a few, fewer than a dozen, several dozen, or even more. Aside from puzzled looks, it is likely that the modal response would be a few or fewer than a dozen.

Then, continue the experiment by asking more specifically how many countries would allow a citizen to do all of the following: take out one or more other citizenships, swear allegiance to a foreign state, vote in foreign elections, hold high office in another country, and/or fight in another country's army even if that country were hostile to the interests of the "home" country. Chances are the looks you receive will change from puzzlement to disbelief. Almost without fail, if you elicit a number at this point, it will be either very small or nil. Then, to complete the experiment, ask if they are aware that the United States is the only country in the world (so far as I can establish) to allow its citizens, natural or naturalized, to do all of these things. If their disbelief has not broadened to astonishment, further inform them that a number of academic, legal, and ethnic activists welcome these developments, and are critical only of the fact that the United States hasn't gone farther, faster to reduce and loosen the ties that bind Americans to their country, instead of helping them to develop identifications and emotional ties to larger and, in their view, more democratic "world communities."

People, even those who are attentive to public life and affairs, are genuinely surprised at the large and rapidly growing number of countries that allow and encourage multiple citizenships. In 1996, a survey by a Hispanic advocacy group studied 17 Latin American countries;19 only seven of those (41 percent) were listed as allowing some form of multiple citizenships. By 2000, only four year later, 14 out of 17 (84 percent) were allowing multiple citizenships and another, Honduras, had a bill to do so pending before its legislature.

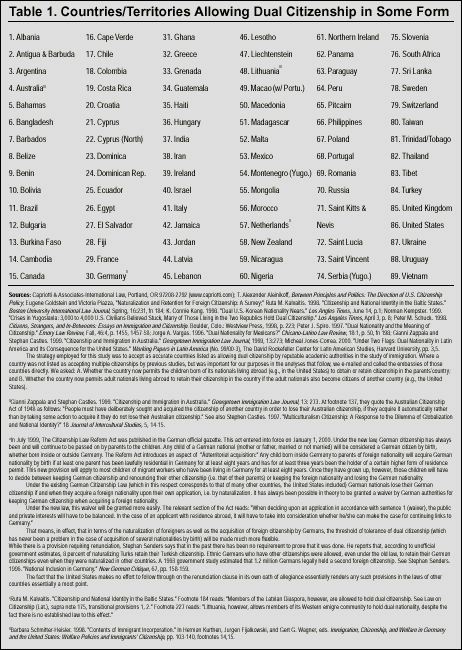

A list of countries allowing or encouraging multiple citizenships is listed in Table 1.

Drawing on several helpful but sometimes inconsistent lists20 in conjunction with my own inquiries, I have established that there are currently 89 countries world-wide that allow some form of multiple citizenship. It is important to underscore, however, that the specific rights and responsibilities that accrue to such citizens vary.

Some countries allow their citizens to become dual citizens but balk at allowing immigrants to their country to do so (Germany).21 New Zealand now permits dual nationality unless, in a specific instance, this "is not conducive to the public good." The French Civil Code formerly provided that any adult who voluntarily accepted another nationality would automatically forfeit French citizenship, but this provision was amended in 1973 so that now "any adult, habitually residing abroad, who voluntarily accepts another nationality will only lose the French nationality if he expressly so declares" (italics mine). Some countries, like Algeria and France, allow their nationals to chose which country's armed forces to join. Others do not.22 Irish citizens in Britain may vote and sit in Parliament. The Irish constitution was changed in 1984 to permit Britons living in the republic to vote in elections to the lower house of the Irish national parliament. Spain does not permit those who hold other Latin American citizenships to vote or stand for election.23 Peru, Argentina, and Columbia allow absentee voting by their dual citizen nations. El Salvador, Panama, Uruguay, and the Dominican Republic do not.24 The new Mexican law creates Mexican dual citizenship (but not dual nationality) and regulates it. Holders of Declaration of Mexican Nationality IDs will not be able to vote or hold political office in Mexico, to serve in the Mexican Armed Forces, or to work aboard Mexican-flagged ships or airlines.25 It is possible to both permit and regulate dual citizenship. Most countries that allow it also restrict it, but not the United States.

This brief survey is not meant to be exhaustive. However, it is meant to underscore one important point: Countries that allow multiple citizenships vary substantially in the specific ways and the extent to which they encourage or limit the responsibilities and advantages of their multi-citizenship nationals.

It would be useful to have an up-to-date survey of the practices of all dual-citizenship-allowing countries. Yet, if additional evidence is consistent with the limited survey above, the United States would surely be among the most, if not the most permissive - having no restrictions whatsoever in any of the wide range of practices that other countries regulate. This seems not to have been so much a matter of conscious public or political choice, but rather the result of one core Supreme Court case26 that has made is virtually impossible to lose one's American citizenship, coupled with the economically, politically, and cultural motivated acts of others countries acting in their own self interest.

So What? Multiple Citizenship and American Immigration

A question arises as to why Americans should care how many other countries allow their nationals to hold multiple citizenships, their motivation for doing so, or the specific ways in which they regulate, encourage, or limit specific responsibilities and entitlements. The answers to these questions are complex and cannot be fully analyzed here. However, surely one key element of the answer has to do with recent patterns of American immigration.

The numbers noted at the beginning of this paper reflect the well-known sea change in the rates and nature of immigration to the United States following Congress' 1965 landmark changes in the country's immigration law. No single number can do justice to the complex array of changes this law has promoted; however, some perspective can be gained from the most recent Census Bureau figures.27

The latest official estimates (1997) of the number of foreign-born persons in the United States is almost twenty-six million (25.8). This is the largest foreign-born population in our history and represents a 30 percent rise (6 million) over the 1990 figures. The number of immigrants for the last few years of the decade stretching from 1990, coupled with the total number of immigrants in the previous decade (1980-90) add up to the largest consecutive two- decade influx of immigrants in the country's history. Half of the foreign-born population is from Latin America, and more than a quarter (28 percent) is from Mexico.

The Census Bureau estimates that the foreign-born share of the population is likely to increase in future years given that group's relative youth and high fertility rates. For example, the average foreign-born household had larger numbers of children under 18 than the average native-born household (1.02 vs. 0.67) Or, to put it another way, 60 percent of those households with at least one foreign-born person living there had one or more children under 18 compared with 45 percent of native households. Foreign-born households were more likely to have two (44 versus 36 percent) or more (16 versus 9 percent) children than native-born households. Of families with a foreign-born householder from Latin America, 25 percent had three or more children. Among married couples with householders from Mexico, this figure is 79 percent.

We have now reached the threshold necessary to begin answering the question: So what?

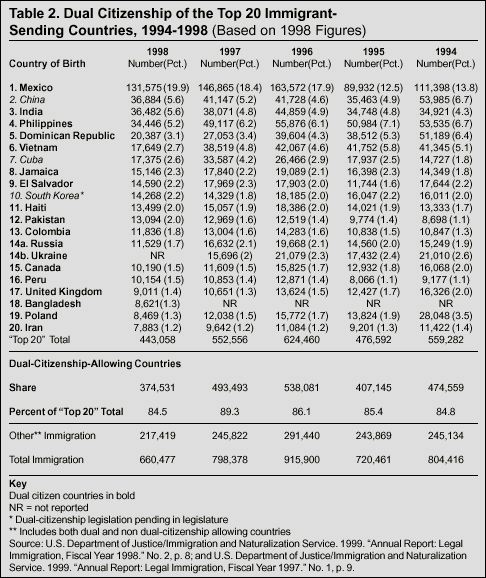

The answer, however, begins with asking another: What is the relationship between the countries that provide the vast pool of immigrants to the United States and the multiple citizenship status of those they send us? Some data are presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2 presents a list of 20 selected high-immigrant-sending countries from the INS official figures for 1994-1998. Those countries that allow their nationals to hold multiple citizenship status are highlighted in bold print. These data show that 17 of these "top 20"28 immigrant-sending countries (85 percent) allow some form of multiple citizenship. Of the remaining three, Korea, is actively considering adopting such legislation.

The numbers for specific years are even more graphic. Of the 443,058 immigrants admitted in 1998 from the top 20 sending countries, 361,437 (84.5 percent) were from multiple-citizenship-allowing countries. In 1997, 493,493 of 552, 556 immigrants from the top 20 sending countries (89.3 percent) were from multiple-citizenship-allowing countries. The figures for the years 1996, 1995, and 1994 are comparable, with multiple-citizenship-allowing countries accounting for 86.1 percent, 85.4 percent and 84.8 percent respectively for each of these years. Overall, of the 2.6 million plus immigrants from the top 20 sending countries, 1994 through 1998, 2.2 million plus (86 percent) were multiple citizenship immigrants.

Recall too, that while 17 of the top 20 immigrant-sending countries are multiple-citizenship-allowing countries, that number represents only a small percentage of the total number (85, not including the United States) of such countries. And, of course, many of these remaining 67 multiple-citizenship-allowing countries send the United States many thousands of immigrants. A more detailed analysis might well find that numbers approaching or exceeding 90 percent of all immigrants come from multiple-citizenship-allowing countries.29

These numbers establish a basic and important fact: American immigration policy, is resulting in the admission of large numbers of persons from countries that have taken legislative steps (for economic, political, and cultural reasons) to maintain and foster their ties with countries from which they emigrated. One may disagree about the importance or implications of these facts, but not with their presence.

So What? Revisited: Some Implications of Multiple Citizenships

The subtitle of this paper is "An Issue of Vast Proportions and Broad Significance." We've examined the proportions, but what of the significance? What are the possible implications of having vast and increasing numbers of residents in the United States with multiple citizenships? Reversing the subtitle somewhat, we can say that the implications of these numerical facts raise issues of vast significance and broad proportions. We can do no more here than note them.

The place to begin is with the implications of these figures for American national identity. The question, "What does it mean to be an American?" has never been easy to answer. It is less so now.

Is there now, or was there ever, a national American identity? If so, of what elements does it consist? Whatever one's answers, and historically there have been many, these are matters of content — whether the focus be ideals, customs, emotional attachments, "creeds," values, or psychologies.30 Less appreciated is another question that has become increasingly prominent in the last four decades: Even if there is an American national identity, is it legitimate to ask immigrants to subscribe to it? Increasingly the answer from immigrant advocates and their political allies is "No."31

Assimilation — with its implications that there is a national American identity and immigrants choosing to come here should, in good faith, try to embrace it — is "contested," to borrow a somewhat dainty post-modern term that hardly does justice to the fierce assault on it as a normative and descriptive model. At one time, that had been both the expectation and the reality.32 It seems obvious that immigrants who enter a country where this view of assimilation is operative and legitimate enter a different country than one in which it is not. It also seems obvious that the potential meaning and implications of having enormous numbers of immigrants entering the United States with dual or multiple attachments to other countries also differs in the two cases.

Again, to state the basics: A country in which the institutional operation and legitimacy of assimilation to its ways of life is under attack and weakened is different than one in which it is not. The first will be more likely to result in the development of alternative psychological attachments and loyalties to countries, traditions, values, customs, ways of viewing the world, and the psychologies that these reflect, than one in which good-faith effort and commitment to assimilation is the operative and legitimate frame of inclusion. Whether one applauds or laments this development in the United States, it is important to keep this fact in view. Arriving in a solidly assimilationist receiving culture is very different from entering a porous and "contested" one. In short, the impact of the enormous numbers of multiple-citizenship immigrants coming to this country varies as a function of the context in which their older and newer attachments unfold.

There is a second element as well to the context in which multiple citizenships unfolds in the United States. The arguments over assimilation assume a stable, coherent culture into which immigrants should (or should not) be assimilated. This is increasingly not the case. The major cultural traditions and values that underlie American national culture have themselves become "contested." That is the meaning of the phrase "culture wars." Though the reality is that there are a series of wars — "science wars," "history wars," "school wars," "military- culture wars," "gender wars," and so on. In addition to these, one must add the political wars that permeate our domestic policy debates from affirmative action to welfare.

Immigrants, whether from countries that allow or discourage multiple citizenships, enter into different cultural circumstances in countries in which the primary culture is stable and secure as opposed to those in which it is not. Conversely, multiple citizenship has different meanings and implications in these two different circumstances. Again, to state the basics: Multiple citizenship immigrants entering a country whose cultural assumptions are fluid and "contested" will find it harder to assimilate, even if they wish to do so and, in such a circumstance, are more likely to maintain former cultural/country attachments that put at risk development and consolidation of newer cultural/county identifications.

It is within the frames of these two critically important contextual elements that the entry of enormous numbers of immigrants from countries that allow and increasingly actively encourage the maintenance and deepening of ties to their "homeland" must be considered. Surely, when over 85 percent of the very large number of immigrants that the United States admits each year are from such countries it is time to carefully consider the implications. When immigrants enter a country in which the assumption that they should be motivated to adapt to the values and traditions of the country is fiercely debated — and the question of "assimilation to what" is increasingly difficult to answer — dual citizenship in America is indeed truly an issue of vast proportions and broad significance.

Notes

1 G. Escobar. 1999. "Immigrants' Ranks Tripled In 29 Years." The Washington Post, January 9, Page A01.

2 Nathan Glazer. 1993. "Is Assimilation Dead?" The Annals of the American Academy of Political Science, 530, pp.122-136.

3 Americans may be slightly more familiar with the term dual citizenship, which denotes holding official citizenship status in at least two separate countries. Yet the term multiple citizenship is the more accurate one, since it covers the holding of two or more citizenships. No country that allows its nationals dual citizenship has any prohibition against holding more than one other. Along similar lines, Jones-Correa notes that a number of South American countries (Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Paraguay) have dual citizenship agreements with other Central American countries or with Spain, which is itself part of the European Union whose common citizenship treaties are being implemented. These countries in turn, have more robust dual citizenship laws for their own citizens and foreign-born nationals. See Michael Jones-Correa. 2000. "Under Two Flags: Dual Nationality in Latin America and Its Consequences for the United States." Working Papers in Latin American Studies, Harvard University, pp. 2,32.

4 Jorge A. Vargas. 1996. "Dual Nationality for Mexicans?" Chicano-Latino Law Review, 18:1, p. 2.

5 Morrison & Foerster LLP. 1997. "Issues Raised by Dual Nationality and Certain Reform Proposals." Draft memorandum prepared for the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, July 13, p. 9.

6 Eugene Goldstein and Victoria Piazza. 1998. "Naturalization and Retention for Foreign Citizenship: A Survey." Interpreter Releases, November 23, 75:45, Appendix I.

7 G. Pascal Zachary. 1998. "Dual Citizenship is a Doubled Edge Sword." The Wall Street Journal, March 25, B1.

8 Peter J. Spiro. 1997. "Dual Nationality and the Meaning of Citizenship," Emory Law Review, Vol. 46, No. 4, p. 1455, fn 199. The Swedish researcher Tomas Hammer reaches similar conclusions about Europe. He says, "The actual number of dual nationals is not known." Moreover, "even now when cases of dual nationality tend to become more numerous, no statistics are kept anywhere in Europe." See Tomas Hammer. 1985. "Dual Citizenship and Political Integration." International Migration Review, Vol., 19, no. 3, p. 445.

9 T. Alexander Aleinikoff. 1998. Between Principles and Politics: The Direction of U.S. Citizenship Policy. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, p. 27. Italics mine.

10 There are variations among other countries in which specific citizenship rights are allowed and under what conditions. Some European countries (e.g. Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland) grant foreign citizens voting rights in local and regional elections. Some Latin American countries that permit or encourage their nationals to gain second citizenships in the United States allow those citizens to vote in elections in their country of origin (e.g., Peru, El Salvador, Colombia), some (e.g., Honduras, Brazil, Mexico) do not. See Tomas Hammar, op. cit.; Rodolfo O. De la Garza, Miguel David Baranoa, Tomas Pachon, Emily Edmunds, Fernando Acosta-Rodriguez, and Michelle Morales. 1996. "Dual Citizenship, Domestic Politics, and Naturalization Rates of Latino Immigrants in the U.S." The Tomas Rivera Center: Policy Brief, June, pp.2-3; and Michael Jones-Correa, op. cit., pp. 3,5.

11 The Department of State now takes the position that intent to denaturalize will not be presumed from an American citizens' foreign naturalization, the taking of a routine oath of allegiance, or acceptance of non-policy-level employment with a foreign government. However, Franck points out that a number of American dual citizens have held rather high positions without loss of citizenship. Raffi Hovannisian became Foreign Minister of Armenia, and stated publicly: "I certainly do not renounce my American citizenship," thus closing off a legal challenge to what he had done. Muhamed Sacirbey, Foreign Minister of Bosnia in 1995-1996, is an American citizen and dual national. The chief of the Estonian army in 1991-1995 also was an American, Aleksander Einseln. Many Americans have served at the United Nations as ambassadors of their other country of citizenship. See, Thomas M. Franck. 1996. "Clan and Superclan: Law Identity and Community in Law and Practice." The American Journal of International Law, 90: 359, July.

12 Following the Supreme Court's 1986 decision in Afroyim v. Rusk (387 U.S. 253), for example, Congress repealed parts of the statutory provisions of American citizenship law. It did this by adding the key requirement that loss of citizenship could occur only on the citizen's "voluntarily performing any of the following acts with the intention of relinquishing United States nationality" [Act of Nov. 14, 1986, § 18, 100 Stat. 3655, 3658 (codified as amended in 8 U.S.C. § 1481 (1988)]. With that, the onus shifted to the Government to demonstrate that a designated act had been performed both voluntarily and with the specific intent to renounce U.S. citizenship. See Franck, op. cit.

13 See Jeffrey R. O'Brien. 1999. "U.S. Dual Citizenship Voting Rights: A Critical Examination of Aleinikoff's Solution." Georgetown Immigration Law Journal. Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 574-75; see also Aleinikoff, op.cit., pp. 26-27.

14 The reasons for ignoring these circumstances vary. A country may simply not perceive the practice as sufficiently important or widespread to merit attention or action. Or, it may serve its own purposes - political, economic, or cultural - by ignoring other ties from which they benefit. Or, the country may have legal prohibitions against the practice, which are weakened by another of that country's political institutions. As Franck points out, Australian law as legislated in 1948 appeared to withdraw citizenship from any Australian who "does any act or thing: (a) the sole or dominant purpose of which, and (b) the effect of which, is to acquire the nationality or citizenship of a foreign country." Yet a recent court case there held that this provision did not apply to an Australian of partly Swiss origin who applied to the Swiss government for recognition of her jus sanguinis status as a Swiss citizen. The case thereby opened the door to recognition of dual nationality since the court held that to lose Australian citizenship, the citizen's motive must have been to acquire Swiss citizenship, rather than to obtain recognition of an already-existing status of foreign nationality. See Franck, op. cit.

15 For example, Jones-Corea offers Bolivia, Honduras, and Venezuela as examples of Latin American countries that allow repatriation upon return. Goldstein and Piazza add Haiti to this list. This is, of course, a form of de facto dual citizenship. This form does not allow an immigrant to exercise formal political rights in his or her country of origin, but to the extent that repatriation is the person's ultimate goal, it may very well affect attachments to a new country. See Goldstein and Piazza, op. cit., p. 1630; and Correa-Jones, op. cit., p. 32.

16 Nationality is often thought of as expressed primarily through emotional attachments, and these are important. Yet it would be a mistake to divorce a person's emotional attachments from the understanding and knowledge that both reflect and inform them.

17 Peter H. Schuck. 1997. "The Functionality of Citizenship." Harvard Law Review, Vol. 110, p. 1817.

18 Stanley A. Renshon. 2000. Dual Citizenship and American National Identity. Center for Immigration Studies: Washington, D.C., forthcoming.

19 Rodolfo O. De la Garza, et al., op. cit.

20 Most discussions of dual citizenship do not attempt comprehensive listings and often are limited by those countries that do and those countries that do not respond to inquiries, or for which information is otherwise available. So, for example, Goldstein and Piazza do not list Ireland (which does permit dual citizenship). More troublesome are inconsistencies that arise from erroneous information or conflicts between what two or more authors assert.

Thus, Goldstein and Piazza list the Philippines and India as non-dual-citizenship countries for American-born children of Philippine and Indian nationals, while Schuck says they are. Along similar lines, Jones-Correa lists Argentina as having dual citizenship (with other treaty countries), while Goldstein and Piazza make no such distinction. And finally, Goldstein and Piazza list the Netherlands as a non-dual-citizenship country, while a Schmitter-Heisler article discusses the effects of the Dutch dual citizenship law passed in 1992. In all cases of differences, inquiries were made of the appropriate embassies. In the few cases where this did not produce clarification, preference was given to the views of authors with established records of scholarship.

21 This, and the examples that follow, are drawn from Franck, op. cit. A new German citizenship law and its implications are detailed elsewhere in this report.

22 Hammer notes that some dual nationals face the risk of having to serve in two different armed forces if they travel to the country in which they hold citizenship/nationality but did not serve. He further notes that other countries, like Turkey, mandate in the constitution that service in the army is a requirement for all citizens, period. See Hammer, op. cit, p.446.

Later evidence, however, suggests Turkey may have modified its position on this somewhat. Miller reports that, at a conference organized by the Alien Commission of the West Berlin Senate in 1989, the Turkish counselor in Berlin said that his government permitted Turkish males living in Germany to pay DM10,000 over a 10-year period to reduce their active time of service in Turkey to two months. See Mark J. Miller. 1991. "Dual Citizenship: A European Norm?" International Migration Review, 33:4, p. 948.

23 Ibid., p. 448.

24 See De la Garza, et al., op.cit., p. 2-3. See also, Jones-Correa, op. cit., pp. 3-5.

25 Philip Martin. 2000. "U.S. and California Reactions to Dual Nationality and Absentee Voting." Foreign Ministry of Mexico, February 17. See also "Mexico: Dual Nationality." Migration News. March 2000, Vol. 7, No. 3. http://migration.ucdavis.edu

26 There are a number of cases relevant to the circumstances that American citizens may give up or lose their citizenship: Perkins v. Elg (1939), Kawakita v. U.S. (1952), Mandoli v. Acheson (1952), Perez v. Brownell (1958), Trop v. Dulles (1958), Schneider v. Rusk (1964), Rogers v. Bellei (1971), Vance v. Terrazas (1980), and Miller v. Albright (1998). The most important case by far, however, is Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967) decided by the U.S. Supreme Court on May 29, 1967. In that ruling, the court held that to sustain a finding of citizenship loss under the (then current) statement and the rules, there must have been forthcoming persuasive evidence establishing that the action taken by the citizen was accompanied by an affirmative intention to transfer allegiance to the country of foreign nationality, abandon allegiance owed to the United States, or otherwise relinquish U.S. citizenship.

See Immigration and Naturalization Service, Interpretations of the Citizenship and Naturalization Law, 350.1. Expatriation in the absence of elective action by persons acquiring dual nationality at birth prior to repeal of section 230.

What does "affirmative intention" mean? On April 1990, the State Department adopted a news set of guidelines fro handling dual citizenship cases. The guidelines assume that a U.S. citizen intends to retain his or her U.S. citizenship, even if he or she is naturalized in a foreign country, takes a routine oath of allegiance to a foreign country, or accepts foreign government employment that is of a "non-policy-level" nature.

So, taking an oath of allegiance to another country is no longer taken as firm evidence of intent to give up U.S. citizenship, even if that oath includes a renunciation of U.S. citizenship. These assumptions do not apply to persons who take a "policy-level" position in a foreign country, are convicted of treason against the United States, or who engage in "conduct which is so inconsistent with retention of U.S. citizenship that it compels a conclusion that [he or she] intended to relinquish U.S. citizenship." The third is unspecified and decided on a case by case basis.

27 The figures that follow are drawn from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census. "Profile of the Foreign Born Population in the United States: 1997." Current Populations Reports Special Studies (P23-195), pp. 8- 49. Definitions of terms used are found in Appendix A, pp. 52-53.

28 U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service. 1999. "Annual Report: Legal Immigration, Fiscal Year, 1998." No. 2, May, p. 8; U.S. Department of Justice/Immigration and Naturalization Service. "Annual Report: Legal Immigration, Fiscal Year, 1997." No. 1, January, p. 9.

Both reports provide legal immigration figures for selected countries for the years they cover. As a result, some additional information is necessary to understand why the term "top-20," while essentially accurate, is in quotes. One anomaly is that neither of the two documents includes the countries making up the former Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, and Slovenia — all multiple-citizenship-allowing countries) in their list of top immigrant-sending countries. Yet with 10,750 immigrants in 1997, and 11,854 in 1996, coming from these countries in those two years, they certainly send more immigrants than several of the countries included in the documents' list of high sending countries. For these reasons, the numbers and percentages of multiple-citizenship country immigrants as a function of the total number of listed "top-20" countries tend to under report their magnitude.

Another anomaly in the table should be noted. The May 1999 report of 1995 through 1998 immigration figures includes one country (Bangladesh) that is not included in the top sending country list in the January 1999 document reporting the immigration figures for 1994 through 1997. The reports follow each of the countries listed back through several previous years. So the May 1999 report contains figures for Bangladesh for the years 1995-1998, even though it is not listed as a top sending country in the earlier January 1999 report, which covered the years 1994 through 1997. In the latter report, the Ukraine is listed as a top immigrant-sending country and its immigrant-sending history is traced back from 1994-1997. However, in that report Bangladesh is not listed. Otherwise the specific countries listed are the same.

To more accurately reflect the realties of the data on high ("top-20") immigrant-sending countries, I have reported the Bangladesh data for 1998, but not for previous years, when the numbers are well below those of the Ukraine which is listed in that "top-20" group in the January 1999 report.

29 As substantial or surprising as these figures may be, they do not tell the whole story of the number of actual or potential multiple citizens arriving and living in the United States. To further deepen our understanding, we would need to turn to two other categorical sources: illegal immigrants and immigrant fertility rates. The reason for this has to do both with the possibility that new or de facto amnesty for illegal aliens might add appreciably to these numbers as well as the fact that children of legal and illegal immigrants are automatically American citizens.

30 Historical views of American national identity coupled with a modern reformulation of the concept may be found in Stanley A. Renshon, "American Identity and the Dilemmas of Cultural Diversity." In Stanley A. Renshon and John Duckitt (eds). Political Psychology: Cultural and Cross Cultural Foundations, London: Macmillan, 2000, pp. 285-310.

31 Ronald Takaki. 1993. A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America. Boston: Little Brown.

32 In an early work on American national character, the English psychoanalyst Geoffrey Gorer wrote, "With few exceptions, the immigrants did not cross the ocean as colonists to reproduce the civilization of their homes on distant shores; with the geographical separation they were prepared to give up, as far as lay in their power, all their past: their language. And the thoughts which that language could express; the laws and allegiances they had been brought up to observe, the values and assured ways of life of their ancestors and former compatriots; even to a large extent their customary ways of eating, of dressing, of living."

This is the immersion into the "melting pot" that colors the myths of both assimilation's advocates and critics. The former see that process as natural and desirable, the latter see it as little better than the cultural rape of immigrant identity. Yet both sides would do well to keep in mind Gorer's answer to the question he raised of why early immigrants might not wish to reproduce their homelands here. The answer was to be in the fact that most immigrants had " escaped . . . from discriminatory laws, rigid hierarchical structures, compulsory military service, and authoritarian limitation of the opportunities open to the enterprising and the goals to which they could aspire.

See Geoffrey Gorer. 1964. The American People: A Study in National Character, Revised Edition. New York: Norton. P. 25. On the ambivalent implications of assimilation, see Peter Skerry. 2000. "Do We Really Want Immigrants to Assimilate?" Society, March/April, pp. 57-62.

Stanley A. Renshon is Professor of Political Science at the City University of New York ([email protected]) a certified psychoanalyst, and the author of six books and over sixty articles.

His psychological biography of President Clinton, High Hopes: The Clinton Presidency and the Politics of Ambition (Routledge, 1998) won the American Political Science Association's Richard E. Neustadt award for the best book on the presidency and the National Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis' Gradiva Award for the best biography. Renshon's latest book, entitled Political Psychology: Cultural and Cross Cultural Foundations (London/Macmillan- New York/New York University Press, 2000) contains his chapter on "American Identity and the Dilemmas of Cultural Diversity" and his next book, One America?: Political Leadership, National Identity, and the Dilemmas of Diversity will be published by Georgetown University Press in 2001.

Dr. Renshon would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance of Ms. Sandra Johnson.