The kind of bundling I am referring to here is not that of the lobbyists-legislators' relationships, another interesting topic, but the placing of disparate groups of would-be immigrants under a single heading, with the heading usually chosen for its curb appeal, not its accuracy.

All too often Congress lumps together quite different groups of would-be immigrants and puts an attractive label on them. There are under the current law "special immigrants," a category that includes both credentialed ministers of religion and juvenile aliens under the thumb of American courts; in immigration speak, both are EB-4 migrants, with the initials standing for Employment-Based.

Similarly, in the bill passed by the Senate earlier this year (SB 744) there is the "staple" provision to grant green cards to all aliens in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) who have advanced degrees from U.S. institutions. This grouping would include people who have labored for five years or more in highly reputable universities to secure valuable PhDs, and other aliens who have just skimmed by in lesser institutions to get two-year's master's degrees. (That the PhDs already tend to stay in America under current law has been ignored by the Senate.)

The mas migration people are constantly telling us that we must import more talent, more of the world's Best and Brightest, but when you examine the fine print of their legislation, you discover that what they want are workers by the droves, so that big business can drive down wages. What we as a nation get, as we show below, is a mix of a few of the best, and many of the banal.

It so happens that under current law there is an allocation of some 40,000 immigrant visas for particularly talented people; this is the EB-1 category for "priority workers" and while 40,000 is a big number, it is also only 4% of the roughly one million immigrants granted legal status each year.

So how much real talent do the EB-1 visas, in fact, produce? And, if getting the best and the brightest is so important, what is the demand for these visas? The answers to both of these questions are, frankly, underwhelming.

Returning to the concept of legislative bundling, the EB-1 category is a collective consisting of four different sub-groupings. There are two obviously useful subsets, "aliens with extraordinary ability" and "outstanding professors or researchers" to quote the law. Then there are the managers and executives of multinational corporations, people who get visas because of the nature of their positions and their ties to a favored set of employers. And finally, the fourth group consists of the spouses and unmarried children under the age of 21 of the other three sets.

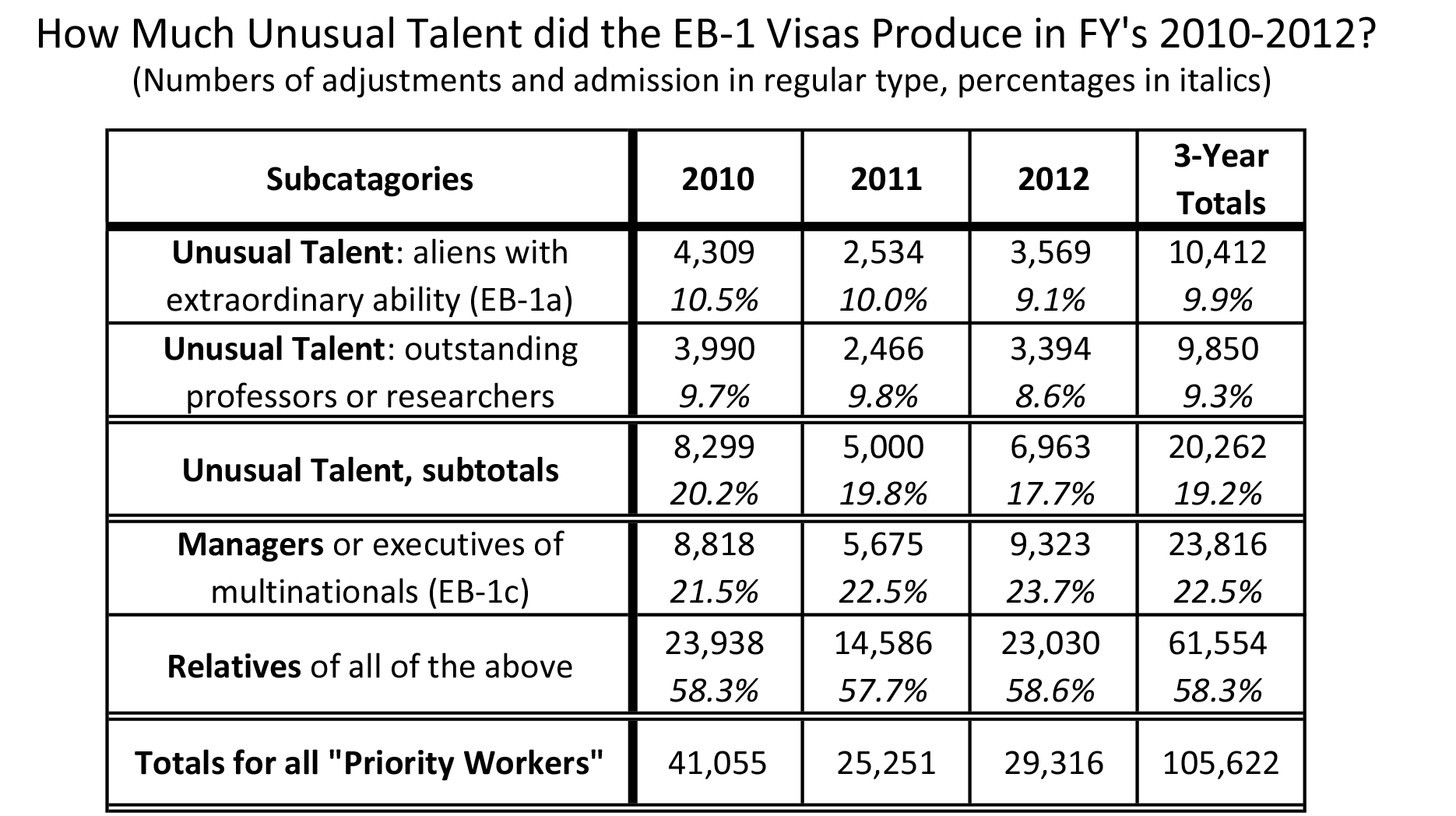

What are the proportions of these four groups? The absolute majority of these "priority workers" are not workers at all, but the spouses and the kids of workers. And as for the other three categories, the multinational managers easily outnumber both the talented groups added together. In 2012, for example, 9.1 percent of the "priority workers" were aliens with extraordinary talent, and 8.6 percent were outstanding professors or researchers, and the other 82.3 percent of the EB-1 category consisted of managers and relatives.

Putting it another way, of the more than 39,000 aliens in the EB-1 category in 2012, fewer than 7,000 of them were in the unusual talent sub-categories.

As the following table shows not only do the multinational managers outnumber the talented classes, they are doing so increasingly as time passes.

There appears to be a dip in all three categories in FY 2011 and a recovery the next year; I do not have a ready explanation for it, except that it must have been a processing issue. There are of course other provisions in the law for the admission of skilled workers, such as the EB-2 and EB-3 categories, but these call for workers of lesser talents or no skills at all.

It should be noted that an EB-1 visa is a very desirable one. Above all, there is no waiting as consistently there are fewer qualified applicants than positions to be filed. And, unlike EB-5 (investors) visas, one need not make investments in the U.S. Further, unlike most EB visas, those in EB-1a do not need to have a job lined up in America. For more on the qualifications needed see this USCIS document.

Although it is the only category for the unusually skilled, and consumes only 4 percent, at most, of our annual intake of immigrants, it has never been over-subscribed in recent years. This is the case presumably because of the average talent levels of the mass of aliens seeking admission, and because of the tough standards set for EB-1a, particularly.

The standards, by the way, are not equally rigorous for all three subclasses of EB-1 principal applicants; they appear to be much tougher on the category of aliens with extraordinary ability; these are perhaps the most valuable group of aliens coming to the States, and so such rigor is probably understandable. One way of determining this is to look at the ratio of appeals to the USCIS in-house review unit, the Administration Appeals Office, bearing in mind that only negative decisions on admissions are appealed to AAO. If the process were equally rigorous for all three subcategories, the ratio of appeals to admissions would be about the same, but as these figures show, they are not.

Ratios of EB-1 Appeals to the AAO to 100 USCIS Approvals, FY 2012

| Extraordinary ability (EB-1a) | 7.9 to 100 |

| Outstanding professors (EB-1b) | 1.2 to 100 |

| Multi-national managers (EB-1c) | 2.9 to 100 |

The number of such appeals was calculated from the AAO's website and compared to the admissions data in the table above.

In other words, these data suggest USCIS was more than twice as likely to turn down an application from an alien claiming extraordinary ability than one claiming that he or she had worked as a manager for a multi-national corporation. The qualifications for the former, presumably, being harder to prove than for the latter.

One final note on the EB-1 population, generally. They are typically not newcomers to the United States. In FY 2012, for example, only 1,517 of the 39,316 were new arrivals, according to the Statistical Yearbook, or less than 4 percent; all the rest were adjustments. While a majority of immigrants each year are really adjustees, the 96 percent portion with the EB-1 population is quite unusual.

Most of the adjustees presumably are currently here in L-1 or L-2 status, as multinational corporate executives and their relatives; and smaller numbers are presumably in the professional non-immigrant classes, such as F, J, H, or O, and their relatives.

To recapitulate: In this category, the most elite of the nation's visa classes, no more than one out of five aliens admitted has unusual talent, and the rest in this category are managers or relatives. These numbers do not speak well for the level of talent within the immigration system currently, or in the new one proposed by the U.S. Senate.

My concern, and my reason for presenting these numbers, is that similar groupings of would-be immigrant would be created by the Senate bill, and that many of the catch-all categories that would be created (e.g., the "stapling" provision) would bring us, in fact, a few very talented people, and many, many others with lesser skills or none at all.