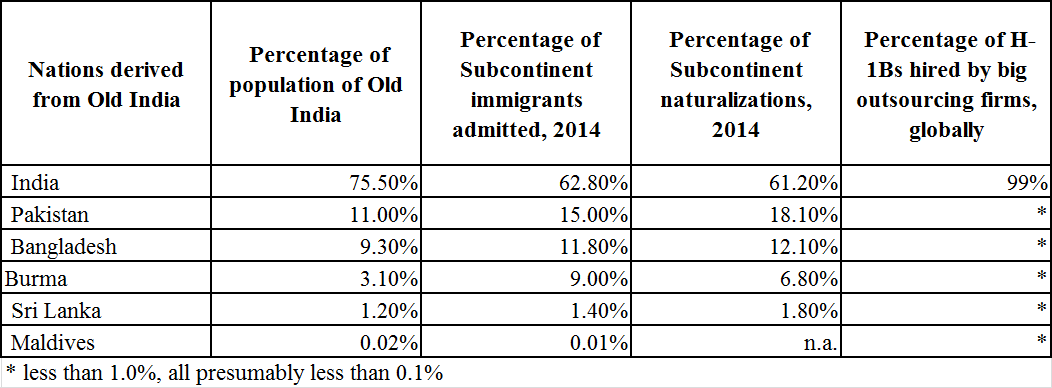

Stimulated by the remarkable level of ethnic discrimination in the hiring practices of the big Indian outsourcing firms – they hire up to 99 percent of their H-1Bs workers from the Republic of India – I decided to take a look at other streams of migration from what the Brits call the Subcontinent.

The major outsourcing companies, such as Infosys and Tata, which rarely employ Americans, hire about 99 percent of their H-1B workers from India; if they pick up any from the other parts of Colonial India, it must be in minuscule numbers. Their decision that the best and the brightest in the world are virtually all young male college graduates between the ages of 22 and 30, and all from a single nation, should secure more negative press attention than it gets.

Back to the Subcontinent: it covers all the nations that used to be part of the Raj, of British India; this includes India per se as well as five nations that have, over the years, spun off from Colonial India. In the order of size of population they are: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma (also known as Myanmar), Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), and the Maldive Islands in the Indian Ocean.

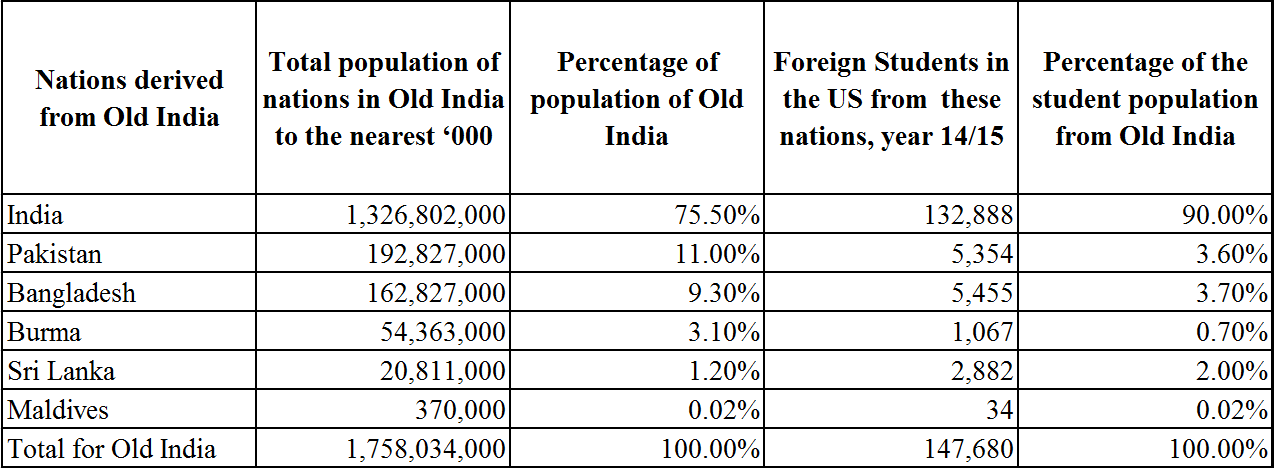

What does migration to the U.S. – other than that of the H-1Bs – look like from what used to be British India? The first comparison made was to the distribution of foreign students in the U.S. from that part of the world (as seen in Table One). New India, with a shade more than 75 percent of the population of old British India, sends 90 percent of the foreign students from the Subcontinent to U.S. colleges and universities. This suggests two things to me: India is wealthier than its immediate neighbors, and there may be a stronger attraction to the U.S. among students there than in the five other nations.

British India's fragmentation might be compared to the post-Tito shattering of Yugoslavia into many pieces, and the post-WWI dissolution of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires. In all these cases the binding forces of the old arrangements gave way to waves of centrifugal forces; in the case of Old India these were predominantly geographical and religious. Two of the spin-offs, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, are islands. Further, India is a mostly Hindu state, Sri Lanka and Burma are majority Buddhist, and the other three are largely Muslim. (No part of the former Raj is particularly good at religious toleration, as various massacres have shown in recent decades. In the case of the smallest and most peaceful of the spin-offs, the Maldives, one cannot even register to vote there unless one is a Muslim.)

It may be total coincidence, but the Muslim parts of the Old India are less likely, as the table shows, to send students to our universities than the Hindu nation of India.

India, incidentally, is second only to China in terms of the numbers of foreign students in the U.S. The number reported in the 2014/15 academic year is 132,888, a large number by any standard; but when compared to the total population of the Republic of India it is only one one-hundredth of one percent of the nation's population, suggesting that there may well be further increases in the numbers of Indian students coming to the U.S.

Table 1

New India Dominates in Distribution of Alien Students from the Subcontinent

So, clearly in terms of H-1B workers and to a lesser extent college students (many of whom go on to H-1B jobs), the new India predominates. This is less true when two other groupings of migrants from the Subcontinent are examined: all new permanent resident aliens, and those holding green cards who opt to become citizens, as the next table shows.

In terms of both arriving immigrants, and aliens naturalizing, from the Subcontinent, the percentages for Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Burma, and to a lesser extent, Sri Lanka, are greater than might be expected by looking at the population of the region generally; these comparisons, and the lower incidence of both H-1B workers and college students from those countries, suggest that the flows of migrants from those parts of the Subcontinent carry with them less human capital than those from India. See Table Two below.

Some to many of the current immigrants from Bangladesh and Pakistan are presumably chain migrants, family members of earlier beneficiaries of the Visa Lottery program; people from those two countries used that program so frequently that these nations are no longer viewed as eligible for the program in that they no longer provide "diversity" in the migration stream. India is also not in the program for the same reason.

Table 2

The Size of Three Migrant Groups (to the U.S.) from the Subcontinent

The Maldives, a string of reefs, perhaps soon to be swamped by the rising ocean, sent us only 13 immigrants in 2014; perhaps one or more of the tiny population of aliens from that country were naturalized in 2014, but DHS statistics did not provide data for that, lumping the newly-naturalized from the Maldives, if any, into a small "all other countries" category.

In a future blog we will look at the ups and downs and complications of migration from Iran.