A recently released Economic Policy Institute (EPI) report may show something surprising: The big U.S. high-tech firms are the ones that are laying off workers, (H-1Bs and citizens) and not the India-based labor brokers.

Or is this an illusion?

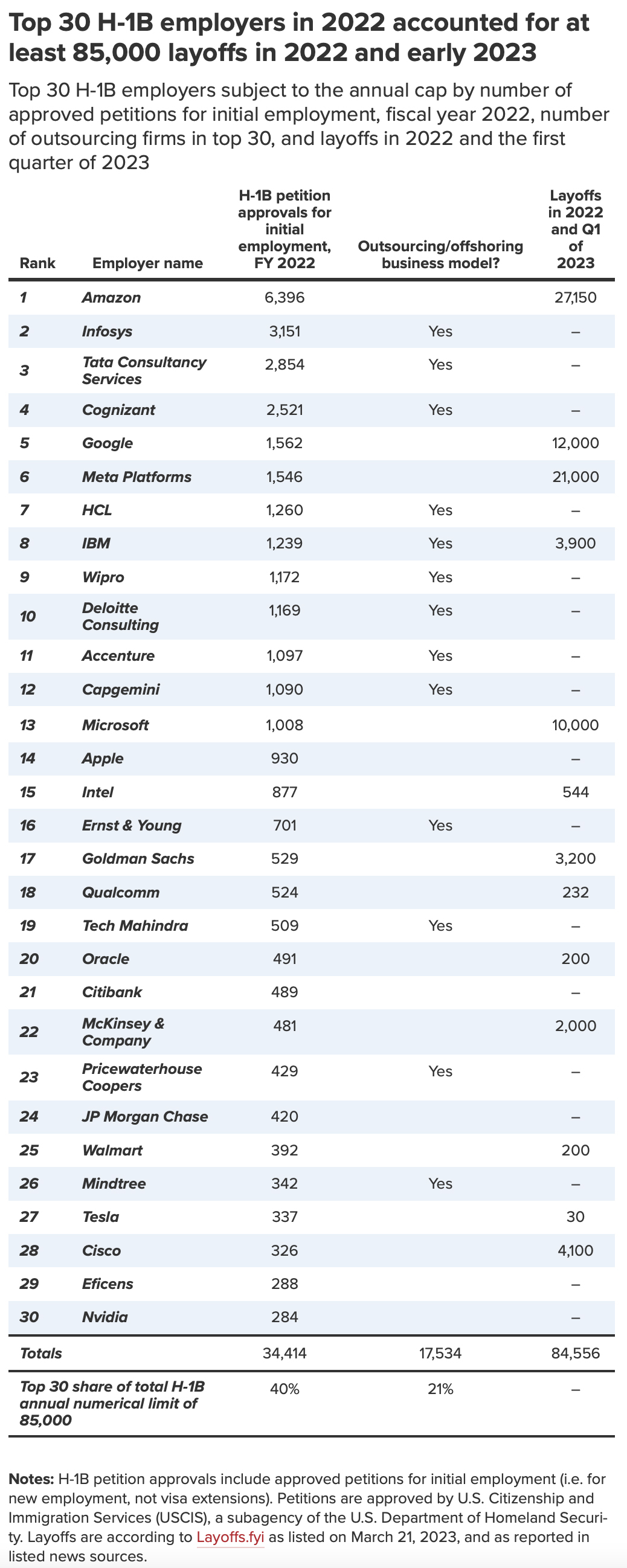

Of the top 30 H-1B employers, EPI counts 13 of them as using the “outsourcing/offshoring business model” (led by Infosys, Tata, and Cognizant) and having a total of 3,900 layoffs in 2022 and the first quarter of this year; on the other hand, the 17 firms that do not meet that description, led by Amazon, Google, and Meta (once Facebook), laid off more than 80,000 workers in the same period.

The authors of the EPI report, EPI staffer Dan Costa and Howard University professor Ron Hira, do not devote much time to this differential, which can be seen in tabular form below; instead they make these sensible public policy points: “Tech and outsourcing companies continued to exploit the H-1B visas at a time of mass layoffs: The top 30 H-1B employers hired 34,000 new H-1B workers in 2022 and laid off at least 85,000 workers in 2022 and early 2023.”

The table from the EPI report that shows the different behavior of the two types of H-1B users follows:

|

One of two things is happening here: Either the labor brokers have found a safe harbor in an otherwise slipping high-tech labor market or, much more likely, they simply are not reporting their layoffs.

As far as I know — and I may be wrong — reporting layoffs and factory closings is a voluntary act in the U.S.; there is no law requiring it, but there is a tradition of doing so. The outsourcing companies on the list — with one notable exception, IBM — may have simply ignored the tradition. IBM, which I would not include in a list of outsourcing companies, is the only one showing any layoffs, and it is a thoroughly American firm.

My takeaway from the table is that the problem with the layoffs is probably a much larger one than we realize because of the silence of the outsourcing firms, and that the extent of layoffs of H-1B workers is even more massive than previously known, all of which make Costa’s and Hira’s conclusions that much more forceful.

We should bear in mind something that has not been reported because it is not happening. Lots of laid-off H-1B workers are well beyond their 60-day grace periods to find another H-1B job or another visa. We have not heard a peep about large-scale departures of them, such as chartering jets to fly from San Francisco to the Subcontinent, because the administration simply is not enforcing this part of the law.

Months ago, when this whole process was getting underway, there were scattered reports of Indian nationals then in India, either on vacation or there to get their visas renewed, finding themselves stuck in the old country. The rule on returning to the old country for a visa renewal has since been suspended or defined out of existence.

Perhaps — but do not wait for it — all H-1B employers of 100 or more workers that lay off more than 20 of these workers should be mandated to report them, complete with the names and addresses of those who have lost their jobs, and hence their claims to legal status. The numerical cut-offs in this proposal would mean that the vast majority of H-1B employers would be exempt.

Meanwhile, in a few days DHS will announce that 85,000 new H-1Bs have been created, all despite the massive layoffs of citizens, green card holders, and H-1Bs in the high-tech industry.