The American immigrant investor program (EB-5) has dozens of competitors for the dollars of the nervous rich seeking another nation's citizenship, or at least a second passport.

This was brought home to me recently by the announcement of a "Citizenship By Investment Property Fair & Conference" to be put on by a Dubai organization, PROMOteam, in a seaside pavilion (once owned by a princely family) in Beirut, Lebanon, on April 30 and May 1 of next year.

This is, apparently, an elegant shopping event in which the rich and restless can look at various nations' "golden visa" schemes and hear lectures on the ins and outs of these programs, all while being in a pleasant and (one hopes) peaceful setting. I would love to be a multilingual fly on the wall, and hear how the competing offers are regarded by those in the position to choose among them.

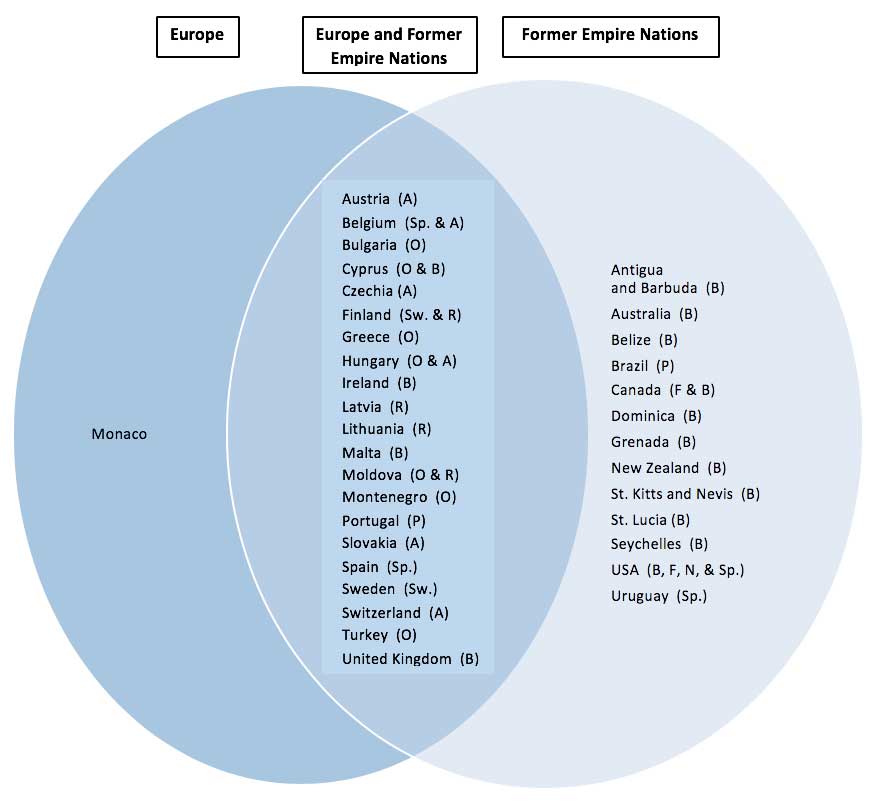

The advertisement for the event carried a list of 36 nations in the golden visa business, which, while not complete, gives a sense of what nations put on such programs, and thus what countries seem to attract, or seek to attract: the insecure, but wealthy investor. We have placed those names in the Venn diagram below.

Nations That Offer Golden Visas to Alien Investors |

|

|

Imperial Initials: A: Austria-Hungary; B: British; F: French; N: Netherlands; O: Ottoman; P: Portuguese; R: Russian; Sp.: Spanish; and Sw.: Swedish. These are broad-brush imperial linkages, and do not reflect some of the islands’ more intricate histories, or the fact that there are lands under the U.S. flag, for example, that once belonged to Denmark, Germany, Japan, and Russia. |

What is instantly clear is that there is a strong pro-Europe bias in this business; every one of the golden visa countries is either in Europe, or is in a nation that once belonged to a Europe-based empire, or both. (For these limited purposes we included the United States with those nations once controlled by one or more European powers.)

On the other hand, no nation in either Asia or Africa offers such a program, or if they do, they are not known to the promoters of the gathering in Beirut, which apparently happens year after year.

Looking at the List. What the list lacks is any measure of the relative success of these various programs. How many rich people are interested in moving to super-poor Moldova, a former part of both the Ottoman and Russian Empires? Do you really want to move your family and your money to Turkey, where the lira is in apparent danger?

And why does Monaco and, particularly, Switzerland, want more rich people?

Missing Nations. Without doing research on all the nations that could be on such a list, I noticed four missing ones immediately, all of which fit in one of the two circles of the diagram.

To be added to the second column is the Netherlands, once the headquarters of a decent-sized empire of its own (it has lost Indonesia and Suriname, but kept six nice islands in the Caribbean). It's asking price is a little over US$1.3 million, still well above the new minimum level of $900,000 recently set for EB-5 visas.

Then there could be, in the third column, three more entries: The Bahamas, a former British colony; the Kingdom of Tonga, a former British protectorate in the South Pacific; and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, in the Central Pacific. The last-named managed to be under four different flags in less than half a century. It started in 1898 as a Spanish colony; then from 1900 to 1914 it was under the German flag; from 1914 to WWII it was under Japanese control; and since then it has been an American mandate, and is now nominally independent.

The Bahamas program focuses on those aliens who build mansions in the islands, while Tonga's and the Marshall Islands' program may well be inactive at the moment.

When Tonga was in this business, several decades ago, it had three diplomatic outposts: one in London to relate to the UK; one in New York, for the UN; and a third in Hong Kong, then a British colony to sell passports. And what was the minimal Tongan price? Though stated in legalistic language, the real price was whatever the market could bear. For a while, the sales did wonders for the islands' finances.

After a short time the American government noticed that the new Tongan passports could be used almost anywhere in the world except in Tonga, and decided that they really did not grant Tongan citizenship, and thus could not be used at U.S. ports of entry. That brought sales to a halt. At the time I was the (very part-time) U.S. correspondent for the then Fiji-based, and now defunct, Pacific Islands Monthly.

The Marshalls' program met the fate of Tonga's efforts, for similar, but not identical, reasons.

The author is grateful to CIS intern James Lochte for producing the Venn diagram.