Download a pdf of this Backgrounder

David North is a CIS fellow who has studied the interaction of immigration and U.S. labor markets for decades.

There is much talk about the need for “comprehensive immigration reform”. With that in mind it would be useful to review what we as a nation learned, or should have learned, from our last big experiment in the field, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA).

It so happens that I had a lot of contact with the IRCA legalization program. Both a major foundation (Ford) and a minor federal agency (the no-longer existing Administrative Conference of the United States) asked me to review and analyze that program, which I did extensively over a period of two years. At the time I thought legalization was a vital part of a genuine bargain, a one-time amnesty to be accompanied by a permanent policy of vigorous immigration law enforcement. That did not turn out to be the case and my views of legalization have changed accordingly.

We should never have another broad-brush amnesty. Such programs swell our already over-swollen population with still more low-income, lightly educated people and encourage future legal and illegal immigration, and thus create arguments for future amnesties. If there is to be a limited program, anyway, let it be tied to actual changes in the law, such as eliminating the diversity visas completely and substantially reducing family preference migration.

That said, but given the wide discussions of the subject, this may be a good time to review IRCA’s major lessons.

- Amnesties without real immigration law enforcement — like IRCA’s — just lead to more illegal immigration, and thus demands for more amnesties.

- It is hard to administer complex, multi-part programs, as in the proposed “comprehensive immigration reform” and as in IRCA. Smaller, narrower programs work better.

- There should be no program specifically for farm workers; agribusiness will surely distort and exploit such a program were it to be enacted.

- IRCA’s amnesty has stretched for more than a quarter of a century — we are still granting benefits to primary IRCA applicants.

- In addition to legalizing about three million primary beneficiaries, IRCA created massive follow-on migration and added huge visa backlogs in the family preference categories.

- A substantial amnesty will attract substantial fraud even when the administering agency — INS in the case of IRCA — has a law-enforcement focus (something USCIS lacks).

- IRCA granted all its beneficiaries a full path to citizenship; if there is to be another amnesty the new benefit package should be less generous and more nuanced.

In order to appreciate these lessons, it would be helpful to review IRCA’s origins and operations; the numerical results of the various parts of the legalization programs, both direct and indirect; the matter of extensive fraud; and the benefits packages and their consequences.

IRCA’s Origins and Operations

The Legislative Environment. At the time of IRCA’s passage, the political atmosphere was considerably less partisan and less rancorous than it is now. Congress was divided, as it is now, but the Republicans had the Senate then and the Democrats had the House. IRCA was essentially worked out by Congress with the Reagan administration and INS playing a relatively minor role in the writing of the law.1

The key players were the chairman of the Senate immigration subcommittee, Sen. Alan Simpson (R-Wyo.), and the ranking member, Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.); the two differed on many issues, but did so in a civil way and they and their staffs respected one another. On the House side Rep. Ron Mazzoli (D-Ky.) was the subcommittee chair and Rep. Dan Lungren (R-Calif.) was the ranking member. Rep. Hamilton Fish, Jr. (R-N.Y.), the kind of moderate Republican that has just about disappeared from the scene, also played a major role on that subcommittee.

After years of hearings, complex negotiations, and committee and floor votes, the two houses passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, and President Reagan signed it into law on November 6, 1986.2

The bill called for employers to verify the legal presence of their workers in the United States and created penalties for those who failed to do so, called employer sanctions. It also created four, soon to be six, separate legalization programs for different groups of unauthorized aliens. Each of the sub-programs related to a different constituency, each had a different set of eligibilities, some had different filing schedules, and some had different reward systems than others. These complexities led to many administrative headaches and ultimately caused the program to be wider and more tolerant of fraud than had been expected.

The four (or five or six) sub-programs were these:

Pre-1982. This was the main program and it gave legal status to those illegal aliens who could claim that they had been in the country since January 1, 1982, and who were residents of the United States when they filed for the program in the period May 1987 to May 1988.

SAWs. There were two sub-sub classes in this program for Special Agricultural Workers, those with 270 or 90 days of farm work (as illegals in this country), with slightly different benefit systems. The SAW provisions of IRCA were worked out separately from the normal legislative process by three then-young Democratic members of the House,3 around a kitchen table on Capitol Hill, an arrangement that met the legislative desires of both agri-business and the farm workers, but led to serious complications in the years that followed. (The SAW provisions were adopted without going through the normal process of hearings and mark-ups). The SAW rules and those in the pre-1982 program differed in many ways, with those for the farm worker program generally more lenient than those for the main-line program.4

Cuban-Haitian Entrants. These were illegal aliens from those two nations (but, in fact, overwhelmingly from Haiti) who had registered with INS before January 1, 1982.

Registry. These were long-term illegals who had been in the nation since January 1, 1972, a small group.

In addition to these four populations, all identified as such in IRCA, there were two other groups that for the purposes of this paper will be regarded as first-round IRCA beneficiaries on the grounds that they were not given legal status through the main-line, ongoing provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).

At the time there was a program very much like the current Temporary Protected Status (TPS) program called Extended Voluntary Departure (EVD). EVD beneficiaries had temporary legal status, but no access to green cards. The program had been applied at different times to relatively small numbers of people from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Poland, and Uganda. Congress on December 22, 1987, decided to merge those enrolled in these small programs into the larger amnesty program, then under way.5

Still later, as part of the Immigration Act of 1990, Congress made specific provisions for about 150,000 dependents of IRCA legalization beneficiaries to become legal residents, again outside the normal workings of the INA.6

The pre-1982s and the SAWs went through a two-step process. First, if their applications were successful, they became Temporary Resident Aliens (TRAs), which gave them legal status in the nation, the ability to work legally, and the right to cross our borders. But in TRA status they could not apply for naturalization, nor could they use the various provisions of the INA to bring in relatives. After a year for some of the SAWs and all of the pre-1982s they moved to green card status; that took two years for the rest of the SAWs.

There were some requirements, not enforced with much enthusiasm, to see to it that the pre-1982s, had some exposure to English instruction and civics lessons.7 There were no such requirements for the SAWs, partly because of the informal procedure used in the design of that program, mentioned above, and partly because agri-business did not want to create anything that could be regarded as an obstacle to their retention of these farm workers.

One of the lessons learned during IRCA was that it was not a good idea to mount a diffuse legalization program aimed at a wide variety of different alien populations. A narrower focus, on a specific population, would lead to a better-regulated, more rational decision-making process.

IRCA Operations. Congress gave INS six months to prepare to run the various IRCA operations, compared to the two months that the president gave USCIS to start the current Delayed Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. INS, seeing the writing on the legislative wall, had been preparing for a legalization program for at least a year before IRCA was signed into law, but it still was an institutional scramble to get the program up and running.

INS, which was then very much an enforcement agency (though it also ran benefit-granting programs) made a Herculean effort to mount the legalization program and to convert large portions of itself into a “welcome the illegals” posture, rather than one focusing on their deportation. At the time the agency was mostly staffed, at the highest levels, by former Border Patrol agents and former investigators. The commissioner, the late Alan Nelson, was a Reagan political appointee and a former prosecutor. (The current agency for such programs, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), has no need for such a transformation, already seeing itself as a benefits-granting agency.)

INS created a whole network of specialized legalization offices, because it did not want to run the program through its then-existing set of enforcement-oriented offices, which it feared would turn off applicants for the programs. It also set up a new decision-making structure, with initial interviews conducted in the new offices, typically by non-INS career staff who made initial recommendations on the applications; the latter were then shipped to four regional centers where the final decisions were to be made.

The notion was that the four regional centers would apply uniform standards to the decision-making process and eliminate the extreme variations in yes-no patterns that were then evident in, for instance, the existing INS naturalization program. At the time I recall Doris Meissner (later Commissioner of INS) telling me that the agency had visited IRS income-tax processing facilities as it sought a useful model for the IRCA decision-making process. Another indication of the agency’s efforts to meet the advocates at least half way was that it conducted a very open and detailed regulation-writing process; in contrast, the Obama administration launched DACA with little more than a White House press release.

I was impressed at the time at the agency’s resolve — and frankly its imagination — as it tackled this new program. But was it a good idea in the first place?

What IRCA Produced

Massive Demographic Results of the IRCA Legalization Programs. The numerical results of the IRCA legalization were remarkable, complex, and continue to this day.

As a yardstick, it is useful to recall that during most of the 1980s immigrant admissions (including adjustments) rocked along at about 600,000 a year.

IRCA directly caused the admission of nearly three million additional people — that would equal the normal nationwide flow over a period of five years — and indirectly the arrival (or adjustment) of millions more. We will review the numbers of direct admissions, compare them to the expectations, and then speculate a little on the huge numbers of follow-on migrants, both legal and illegal, related to the direct IRCA beneficiaries.

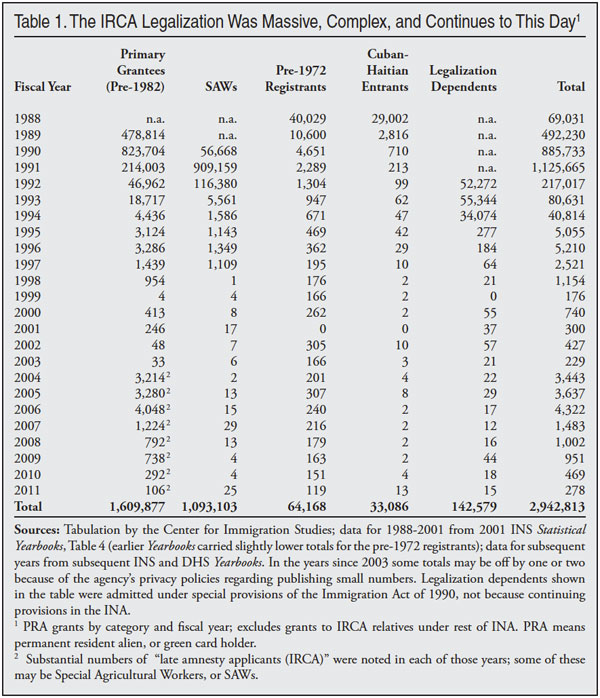

Table 1 shows the distribution of IRCA’s legalized populations, as they have been processed into our nation over the period 1988 through 2011, with the total number of beneficiaries, as we have defined them, coming to 2,942,813. Most of these were in the pre-1982 program (about 1.6 million) or the SAW program (1.1 million). Those in the other three categories totaled about a quarter of a million. All data are from the Statistical Yearbooks.

Those in Table 1 are all direct beneficiaries of the IRCA program; that the numbers are large is well known; that the number of additional adjustments (and some admissions) continues to this day may not be widely recognized. The stretching out of the program relates to a number of causes, such as slow decision-making on the part of various institutions, the largely successful efforts of the immigration bar and the courts to expand the definition of eligibility over the years, and some after-the-fact efforts of Congress to do the same thing.8

So one of the lessons from IRCA is that amnesties tend to go on for a long, long time, even if the focus is only on the direct program beneficiaries.

We have some data on the characteristics of those who received benefits under the pre-1982 program, who tended to be a bit better educated than the SAWs.

A survey of 6,200 members of that population, conducted by Westat Inc.,9 an INS contractor, in 1989 showed that 70 percent were from Mexico, that they had a median of seven years of education, and were 58 percent male and 42 percent female. Three-quarters of them had never been apprehended by the INS, an indication of the effectiveness of INA enforcement at the time. There were proportionately more men, and more Mexican nationals, in the SAW population than among the pre-1982s.

How did the number of these direct beneficiaries of IRCA compare to the government’s expectations? INS estimates, according to Baker,10 were approximately correct for the pre-1982 population, but terribly wrong for the SAWs. INS demographers were expecting 210,000 SAW applications in the five states using the most farm workers, but the agency received 1,031,600 of them in those states. The INS staff probably was about right about the number of people eligible for the program, but the actual applications reflected a remarkable level of fraud that was not anticipated, a point to which we will return.

Follow-on Migration. So far I have been describing only the direct results of IRCA, but since amnesties legalize the presence of people in previously illegal status, once they get their new green card status they are eligible to start importing their relatives. If they take one more step and become citizens they become eligible to import still more relatives.

As a matter of fact, I identified four classes of follow-on migration from IRCA:

- Those legally admitted who are directly related to the primary beneficiaries.

- Those legally admitted later who are directly related to those in class 1 and less directly to the original beneficiaries, and those who are related, in turn, to the population in group 2. This is a self-perpetuating follow-on population.

- People who are related to either direct or follow-on populations (like 1 and 2 above), who have not yet been admitted, but who have (backlogged) visas.

- Finally, people related to direct beneficiaries or follow-on migrants who are in the United States illegally.

There is obviously some overlap between populations 3 and 4.

Granted that there are these four populations of follow-on migrants, how large are they?

My sense is that they number in the millions, but that the size of only the first population — the relatives of the direct beneficiaries — can be estimated with any degree of accuracy.

The appendix contains a detailed estimate for the numbers of immediate follow-on migrants, all related to the IRCA beneficiaries. My conservative, perhaps ultra-conservative, estimate is that about 743,000 immediate follow-on migrants came to the United States or adjusted status in the years 1991 through 2012. Remember that this estimate is for only one of the four follow-on migrations started by IRCA and that this migration continues to this day. Similar sets of echo migrations are sure to follow any new amnesty unless the benefit packages are not changed from those used in IRCA.

As noted in the appendix, the relative admission policies of the United States are much more generous to citizens than to green card holders and that fact, together with the fact that most of the IRCA grantees had not sought citizenship by 2009, decreased this primary flow of follow-on immigrants well below what might have been expected had a higher percentage of the original beneficiaries opted for naturalization.

While my estimate is for all IRCA-related follow-on migrations that actually happened, another immigration watcher, Karen A. Woodrow-Lafield, writing for the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform (the Jordan Commission), focused on the potential demand for visas to be filed by IRCA beneficiaries.11 One of her illustrative numbers indicated that nearly 1.9 million such visas could “possibly be filed under family preference and immediate relatives categories under sponsorship of generally legalized immigrants.” Her basis was a survey of the visa intentions of the IRCA beneficiaries.

Her estimate would cover most of subpopulations 1, 3, and 4 described above; without examining her methodology in detail, it is useful to point out that here is a different observer, looking at the basic follow-on migration situation in a different way and coming up with another very large number.

Speaking of both visa petitions and large numbers, it is instructive to look at the backlogged family petitions for Mexico — a total of more than 1.3 million — many of which must have been IRCA-created. See Table 2.

One of these backlogs is now 20 years old, four out of the five are more than 15 years old, and they constitute about one-third of the world-wide collection of waiting periods for family admissions. That number is an astonishing 4,299,635.12

Incidentally, the backlogs developed in the wake of the IRCA amnesty not only create long waits for would-be immigrants from Mexico, they also extend the waiting time for other potential family immigrants from elsewhere in the world. IRCA, in short, by adding to the general, world-wide delays caused relatives of U.S. residents of Chinese extraction, for example, to wait longer than they would have otherwise.

In many cases the Mexican backlogs were in being many years ago when the IRCA beneficiaries from that country got their green cards. All of this suggests that we should send these applicants a refund for their visa fees and eliminate the program entirely.

These backlogs are not just total numbers of people with the potential of migrating to the United States, waiting quietly in Mexico to cross the border when their number finally comes up — and getting older in the process. Many of those in the backlog are in the United States, mostly illegally, but some with nonimmigrant visas. Further, and equally important, the presence of these backlogs is used by the more-migration forces as an argument to lift these restrictions and allow the immediate admission of all or most of these potential migrants.

When those advocates discuss these backlogs, by the way, they always do so in terms of the U.S. immigration law causing the break-up of migrant families; it is never mentioned that these non-family reunions are always the result of volunteer acts of individual ambitious (or restless) international migrants, nor that the “disrupted” families, in most cases, can be re-united in the migrant’s home country.

Another lesson from IRCA, then, is that no amnesty should create backlogs that will lead to further attempts to change the law in the direction of additional migration to take care of the backlogs created by the amnesty.

Fraud in the IRCA Amnesty. Fraud occurs in a benefit program when two elements are present: the reward for filing the application is significant to the rewardee and the definitions of eligibility are such that some are eligible and some are not.13 With IRCA, the benefits of legalization were, indeed, significant, and many illegal aliens were eligible for it, but many were not.

As noted above, IRCA was not a single program, it was a group of them, with different eligibilities for each. In the case of IRCA, the requirements for the SAW program were much less demanding than for the other programs, so there was very little fraud in the pre-1982 and the specialized programs, it all migrated to the SAW program. It was easier to claim that you had spent 90 days in farm work than that you had lived in the nation for about five years.

INS made a real effort to detect fraud and to deny fraudulent legalization applications, particularly early in the IRCA program. For example, it had actual face-to-face interviews with applicants and it published approval and denial data. The interviewers made recommendations for denials or approvals, and these, as noted earlier, were sent to the four regional offices where final decisions were made.

In contrast, there is USCIS’s handling of these variables in the current DACA program: There are no routine interviews (there are some sample interviews, however). All decisions are made in the four centers based on the documents submitted. Further, to this date the agency has not announced any denials in the program — not one — just receipts of applications and approvals.14 With precedents such as these, one worries that there will be no genuine effort to root out fraud in DACA or any other future amnesty program run by the current administration.

Back to IRCA. Despite INS’s initial efforts, everyone agrees that there was extensive fraud in the program, particularly in the SAW portion of it. My CIS colleague, Steven Camarota, for example, estimated that fully one quarter of the applications were fraudulent,15 and Susan Baker provided a comprehensive summary of the administrative and judicial forces that inhibited INS’s efforts to fight fraud.16

One unpublished bit of data on how fraud was handled in the IRCA program was described in my previously mentioned Backgrounder:17

As a matter of fact, we found unpublished INS data showing 882,637 legalization-office-recommended denials on March 24, 1989, as well as more than 300,000 pending cases. By the time the program closed its books, there were only 351,745 non-grants of legal status (we assume that this concept and that of a case denial are the same or approximately the same.)

Not only did INS overturn most interview-level denial recommendations, it also siphoned off funds that could have been used to detect fraud, as noted in the same source:

One nicely documented example of such a transfer was reported by Interpreter Releases, the immigration bar’s scholarly trade paper; an Assistant INS Commissioner announced that $50 million in what he termed excess SAW fees were going to be used to buy INS a whole new generation of computers. When I reported, during the Ford-supported research, that this money could have been, and should have been, used to identify fraudulent SAW applicants, that Assistant Commissioner (who will remain nameless) literally screamed at me; I had apparently touched a raw nerve.

So two more lessons to be learned from the IRCA program: Expect massive fraud in any amnesty and do not divert amnesty fees to other public purposes.

If There Is to Be Another Amnesty …

It is perfectly possible to design an amnesty program that will produce much less harmful follow-on migration consequences than those set in motion by IRCA.

There are two alternative ways of meeting that goal: Change the basic rules regarding follow-on migration created by immigrants, generally, or give the newly-amnestied a free pass to the U.S. labor market, but only limited access, if any, to follow-on migration.

I prefer the first approach on the grounds that reducing legal migration, generally, is something the country needs now, and has needed for a long time. Further, it avoids the creation of a sort of second-class immigrant, who gets some of the benefits of life in the United States (such as legal access to the labor market and the Social Security system), but no or limited access to immigration benefits for that person’s relatives. The creation of such a class of immigrants would, of course, lead to extensive lobbying to obtain full green card rights for this population on the grounds of “equal rights for all immigrants”.

Ideally, in exchange for a narrowly tailored amnesty (say for those now getting temporary legal status under DACA), we would eliminate, for all time, the following classes of potential immigrants:

- The entire diversity visa program (routinely 50,000 slots a year);

- Family preference one, unmarried adult children of U.S. citizens (23,400 a year);

- Family preference three, married adult children of U.S. citizens (23,400 a year); and

- Family preference four, siblings, siblings-in-law, and nieces and nephews of U.S. citizens (65,000 a year).

We should also eliminate all of the unskilled workers from the employment-based preference classes and the unmarried adult children of permanent resident aliens, now in the second family preference (these two steps would reduce immigration by several tens of thousands a year.)

Alternatively, we could make the newly amnestied less qualified to set in motion additional migration. One possibility, as suggested by Peter Skerry in the Los Angeles Times would be:

With as few conditions and as broadly as possible, we should offer undocumented immigrants status as “permanent noncitizen residents”. Unlike current green card holders, these individuals would never have the option of naturalizing and becoming U.S. citizens. The only exception would be for minors who arrived here with their parents. Provided they have not committed any serious crimes, such individuals should be immediately eligible for citizenship.18

While the basic concept of a legalization program not leading to citizenship is worth considering, I do not agree with Skerry’s “broadly as possible” approach, nor with his exception in favor of minors arriving illegally with their parents; this would allow too much room for fraudulent applications — how do you prove that the 25-year-old entered the nation with his parents, illegally, at the age of 15, for instance, rather than crossing by himself at that age or some other?

Another possibility in this field is to follow a precedent set a few years back when the lightly-populated island republics in the Central Pacific — formerly Spanish, then German, then Japanese and then U.S. colonies — came out from under the United Nations mandate and became the Freely Associated States of Palau, the Republic of the Marshal Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia.19 Congress decided to give the citizens of those islands the life-long right to migrate to, and work in, the United States and its territories, thus becoming a permanent nonimmigrant class that carried no rights to move to either green card or citizen status.20 Thus a Paluan (and there about 15,000 of them) would never be able to use his or her legal status in the United States to bring in any relatives.

This would produce an amnestied population that would be able to work here, and perhaps join the Social Security system, but not cause any secondary migration at all.

Another, less drastic alternative would be to allow the new amnesty beneficiaries to become holders of specialized green cards, in which they could cause, in the future, the legal admission of spouses and small children (as in the family second preference), but would be permanently barred from creating visas to be issued to their parents, their adult children, their siblings and siblings-in-law, and their nieces and nephews. There would be no path to citizenship for these amnestied people, unless, of course, they managed to secure a green card under the general provisions of the INA.21

We might think about such a benefits package if Congress will not restrict family preferences broadly as suggested above.

Whatever the exact status of the newly amnestied, it would be useful to give them a non-romantic title, such as Skerry’s “permanent non-citizen residents” (PNCR’s?) or better, temporary alien workers (TAWs). The rhetorical implications of a term like DREAMers, for example, should be avoided.

It might also be helpful if the newly amnestied were told that they could keep this status as long as they paid their federal and state taxes and stayed out of serious trouble with the law — and that a virtually automatic deportation faced them if they fell out of status.

In any legalization program, we are forgiving the newly amnestied for their past violations, after all, and we should not be granting them unlimited benefits because of their past behavior. Any amount of amnesty, any benefit package, should be regarded as a boon, and the not the long-delayed recognition of a right.

The conversation about the right mix of benefits, just like the discussion of the appropriate tax code, should be nuanced and precise, with neither a full freedom from all taxation, nor a full pathway to citizenship, on the table.

Appendix: Estimating the Follow-on Immigration Created by the IRCA Amnesty

As noted in the text of this report, I estimate that the initial (primary) follow-on legal immigration created because of the IRCA amnesty is 743,000 for the years 1989 through 2012.

It is necessary to estimate this number because a careless government (perhaps not wanting to know the real numbers) has not counted the follow-on migrants as it could have had it wanted that information.

The 743,000 is only one of the post-IRCA immigration consequences of that amnesty program; in addition to those follow-on immigrants there are three other migratory streams:

- Aliens who have been admitted because they are related to the group of 743,000; these might be called the secondary follow-on legal migrants; this population and its own follow-on populations will keep arriving for decades;

- Aliens who are relatives of IRCA-amnesty families who are now on various visa waiting lists, some of whom have nonimmigrant visas (V or K-3) that allow them to wait, legally, in the United States; and

- Aliens who are members of IRCA amnesty families who are now in the United States illegally, probably hoping for yet another amnesty.

Sub-populations 2 and 3 overlap to an unknown extent.

Estimating the number of primary, legal follow-on migrants is difficult enough without attempting to do anything with the other three subpopulations, some of which are probably very large, so I am offering no estimates of their sizes, but merely note their presence.

In general terms, the estimate of the primary group of follow-on migrants is based on the assumption that the three million newly legalized foreign-born will create additional family migration at a rate that is about the rate of visa-creation caused by other parts of the legally present foreign-born (FB hereafter) population. Some data are available on that subject.

This is an essentially conservative estimate because the amnestied population is — in comparison to the entire resident FB population — newly arrived, and thus more likely to be in touch with family in the homeland than say, a 70-year-old former resident of Italy who came to this country at the age of two, some 68 years ago. Both the 70-year-old Italian and the newly amnestied are equally FB, but a member of the first group is more likely to cause additional migration than is the 70-year-old.

More specifically, my estimate of the primary follow-on migrants is based on the rates by which two different foreign-born populations generate follow-on migration; these are naturalized citizens and green card holders. There are provisions in the law for the relatives of each subgroup; more generous for citizens, generally, and less so for those with green cards.

As we will see, most amnestied aliens did not opt for citizenship, so most of the IRCA beneficiaries did not have access to the more generous relative provisions of the INA and thus the follow-on legal migration consequences are not as large as one might have imagined.

Another factor, working in the same direction, was the congressional decision, made in 1996, that if one had been in the United States illegally for 180 days after April 1, 1997, one needed either to be absent from the United States for three years or to obtain a waiver before seeking to convert to legal status. Similarly, if the illegal presence was a year or more, then there was a 10-year absence requirement, again capable of being waived. While most waiver requests were granted, this provision served to slow, or, in some cases to deny, legal entry to some of the follow-on migrants.

On January 2, 2013, DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano announced that a new system for obtaining these waivers will be available in March in the United States, rather than at U.S. consulates in other nations. This will speed this process for some illegals currently in the United States, but this factor was not operative during the period of my estimate.

Returning to the estimation process, the first step, as shown in Table 3, is to obtain benchmark data on the extent to which the two sets of relative preferences were used nationally by all foreign-born during the period of interest (1991 through 2012). I used different years, eight years apart, in column 2 to show that some of these flows (e.g., young children in the immediate relative category) have been pretty constant, while others, such as immediate relative/spouses of citizens, have increased remarkably. Generally, as the table shows, relatives of green card holders were admitted at about one-third the rate of relatives of citizens. Data on these flows are drawn from the immigration agencies’ annual reports.

Next, column 4 in the table deals with the percentage of sponsors of immigrants generally who were foreign-born. This is a necessary step in the calculation because the sponsors of relative immigration include both native-born citizens and naturalized ones. In the case of the amnestied sponsors, all were naturalized citizens and thus the number of IRCA citizen sponsors should be compared only to the number of naturalized citizen sponsors of relative-immigrants, not all the citizen sponsors.

There is no estimation problem with the green card sponsors, as all are foreign-born, but we need to figure out what percentage of the citizen sponsors, generally, are foreign-born. I know of no data on the subject and have had to rely on common sense to arrive at these estimates.

Let’s take citizens seeking to bring their parents to this country. It is unlikely that many native-born citizens have non-citizen parents, or siblings for that matter. So I estimate that 90 percent of the sponsors in these categories are naturalized citizens.

Then there is the category of spouses of citizens. Many native-born citizens marry spouses from other countries, and the number of native-born citizens dwarfs the number of naturalized citizens.22 On the other hand, naturalized citizens are probably more likely to marry aliens, much more likely, in fact, than the native-born. I have guestimated that 40 percent of the sponsors of immediate relative alien spouses are naturalized.

The next variable (in column 5) is the percentage of the two potential sponsor populations, those with green cards and the naturalized, who were IRCA beneficiaries. Fortunately, there is an Office of Immigration Statistics report that deals with the extent to which the IRCA beneficiaries had become naturalized by the end of 2009.23

That report shows that 53 percent of the pre-1982 (main-line) beneficiaries had become naturalized at the end of 2009, compared to 34 percent of the farm workers (the SAWs). I assume that by the end of 2012 those two numbers had climbed slightly, to 56 percent for the first group and 36 percent for the second.

I also assumed that the rate of naturalization for the three smaller IRCA amnesty populations, the registrants, the Cuban-Haitian entrants, and the IRCA-recognized dependents, was about the same as that of the pre-1982 population.

I further assumed that the number of people naturalizing, in both subpopulations, was larger in the first few years of the main period of eligibility (1995-2012) than later. With all that in mind I calculated that the average number of naturalized IRCA beneficiaries during that time period was 37 percent for the main group and 24 percent for the SAWs; both of those numbers are two-thirds of the estimated 2012 naturalization figures, which were 56 percent for the pre-1982 population and 36 percent for the SAWs. (One could make other estimates, but these seem to be roughly appropriate.)

When these percentages (37 percent and 24 percent) are applied to the totals in Table 1, we get an estimated average population of 685,000 citizens for the main group, and 262,000 for the SAWs. This produces an average population of citizens in this time period of 947,000, compared to 1,953,000 green card holders. The persisting dominance of the green card holders in the amnesty population presumably considerably depressed the primary follow-on legal migration started by IRCA.

The next step in this iterative process was to figure out what percentage of the total national green card population related to IRCA and, similarly, what percentage of the total naturalized citizen population were IRCA beneficiaries midway through the periods of interest. These were 1990-2012 for the green carders and 1995-2012 for the naturalized citizens. Most of the IRCA people had green cards by 1990, and most of them were eligible for naturalization five years later, in 1995, as can be seen in Table 1.

Using Census data for the years 2000 and 2010,24 I estimated the total naturalized population in the in United States in 2004 at 14.5 million. Since the average number of IRCA beneficiaries who were naturalized at that time was 947,000, that means that they constituted about 6.5 percent of the naturalized citizen population, as shown in column 5.

Meanwhile, the IRCA beneficiaries constituted a larger percentage of the average green card population in the period of interest; there were some 1,953,000 of them. In comparison, there were, according to Office of Immigration Statistics estimates,25 about 11.5 million green carders at the time, which means that the IRCA percentage is about 17 percent.

There were, as shown in column 6, 22 years of green card status, and 17 years of citizen status in which family relative petitions could be filed.

Column 7 shows the average estimated annual flows of immigrants in each of the categories based on data in columns 2, 3, 4, and 5. These are multiplied by the years of eligibility in column 6, and totaled in column 8.

As noted earlier, this is probably a very conservative estimate of just one of four of the follow-on migrations caused by the IRCA legalization program.

End Notes

1 This part of this report is largely drawn from my 2010 CIS Backgrounder “A Bailout for Illegal Immigrants: Lessons from the Implementation of the 1986 IRCA Amnesty”, which is a more detailed document than this one.

2 Pub.L. 99-603, 100 Stat. 3359. For a good description of the political and legislative background of this legislation, see Susan González Baker, The Cautious Welcome: The Legalization Programs of the Immigration Reform and Control Act, Washington, D.C.: The Rand Corporation and The Urban Institute, 1990, pp. 25-44.

3 The trio were Howard Berman (D-Calif.), who completed his long tenure in the House earlier this month, Leon Panetta (D-Calif.), now Secretary of Defense, and Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.), now chair of the Senate’s immigration subcommittee, with Berman speaking for the workers, Panetta for the employers, and Schumer playing dealmaker. For more on this see the Ford-funded report: David North and Anna Mary Portz, The U.S Alien Legalization Program, Washington, D.C.: TransCentury Development Associates, 1989 (out of print) pp. 11-13. Ms. Portz, incidentally, while an honored co-author of that report, and now with the State Department, was not involved in the writing of this report.

4 There was also a stand-by provision in IRCA for the creation of a third class of alien farm workers, Replacement Agricultural Workers (RAWs) should labor shortages develop in agriculture in following years. No such shortage appeared and the provision, thankfully, was never implemented.

5 I know of no separate statistics on these one-time EVD populations.

6 See 1992 Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., 1993, p. 13.

7 Currently the feeble education requirement in DACA is that the applicant must be enrolled in an educational program on the day the amnesty application is filed; there is no requirement that the alien must stay in the program. In IRCA there was a somewhat similar provision, that the alien seeking to complete the second phase of legalization could either take a test (repeatedly if necessary) or could file a certificate from an educational entity that the alien was “satisfactorily pursuing” the civics and English instruction. Only a small minority actually took the test. See North-Portz op. cit., pp. 101-102.

8 Such as the passage in 2000 of the Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act which facilitated certain class action litigation on behalf of groups of once-denied IRCA applicants.

9 Immigration Reform and Control Act: Report on the Legalized Alien Population, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Washington, D.C., 1992. I was a consultant to this research project, but did not write the report.

10 Baker op. cit., p. 165.

11 Karen A Woodrow-Lafield Potential Sponsorship by IRCA-Legalized Immigrants, U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, Washington, D.C., 1994, p. 26.

12 For more on these backlogs, see Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-based preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2012, Visa Office, U.S. Department of State.

13 There would be no need for fraud if the eligibility rules were simply that you had to be in the country on the day you applied for the benefit.

14 Currently, we have learned from USCIS “stakeholders’ meetings” on the subject, that while there are no published DACA denial statistics, there is a category called “rejections” in which the agency does not accept the application and sends it back on the grounds of its being incomplete or lacking the appropriate fee. Such applications can be re-submitted.

15 See Steven A. Camarota “Amnesty Under Hagel-Martinez: An Estimate of How Many Will Legalize if S 2611 Becomes Law”, Center for Immigration Studies, September 2009.

16 See Baker op. cit., p. 156-157.

17 See end note 1. That document also describes alternative applicant interview models in some detail. It concludes that there should be face-to-face interviews, as there were in IRCA, and that people with feeble applications should be given opportunity at the time to withdraw their applications and get their fees refunded without further agency action.

18 Peter Skerry, “A third way on immigration: Instead of deportation or amnesty, the U.S. should adopt legalization without citizenship”, the Los Angeles Times, December 16, 2012. A longer exploration by Skerry of this idea, “Splitting the Difference on Illegal Immigration”, was published in the Winter 2013 issue of National Affairs.

19 For a few weeks in my long and checkered career, I supervised the Department of Interior’s handful of staff members in those islands.

20 Shortly after Congress made that decision, the ever-resourceful local politicians in the Marshall Islands started selling full-citizenship passports to wealthy residents of China. At first sales were brisk, particularly in Hong Kong, but sales fell sharply when our State Department decided that such passports could be used to secure admission to the United States only if the holders had, in fact, met the Marshalls’ naturalization standards of five years’ actual residence in the islands.

21 We might consider, however, a path to a green card, but only for amnesty beneficiaries who do something significant for the country, such as serving in military for at least four years and getting a good discharge; serving in the Peace Corps for three years after obtaining U.S. college degree from a recognized non-profit institution; or earning a PhD or an MD from a similar institution. This would be designed to be a narrow path for the most useful minority of the newly amnestied, not for the bulk of that population.

22 The ratio of native-born citizens of all ages to naturalized citizens of all ages is currently about 15 to one, according to Nativity Status and Citizenship in the United States: 2009, American Community Survey Briefs, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C., 2010.

23 Bryan C. Baker, Naturalization Rates among IRCA Immigrants: A 2009 Update, Office of Immigration Statistics, DHS, Washington DC, 2010.

24 The Foreign-Born Population: 2000, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C., 2001; and The Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 2010, American Community Survey Reports, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington D.C., 2012.

25 Nancy F. Rytina, Estimates of the Legal Permanent Resident Population and Population Eligible to Naturalize in 2002, Office of Immigration Statistics, DHS, Washington, D.C., 2004.