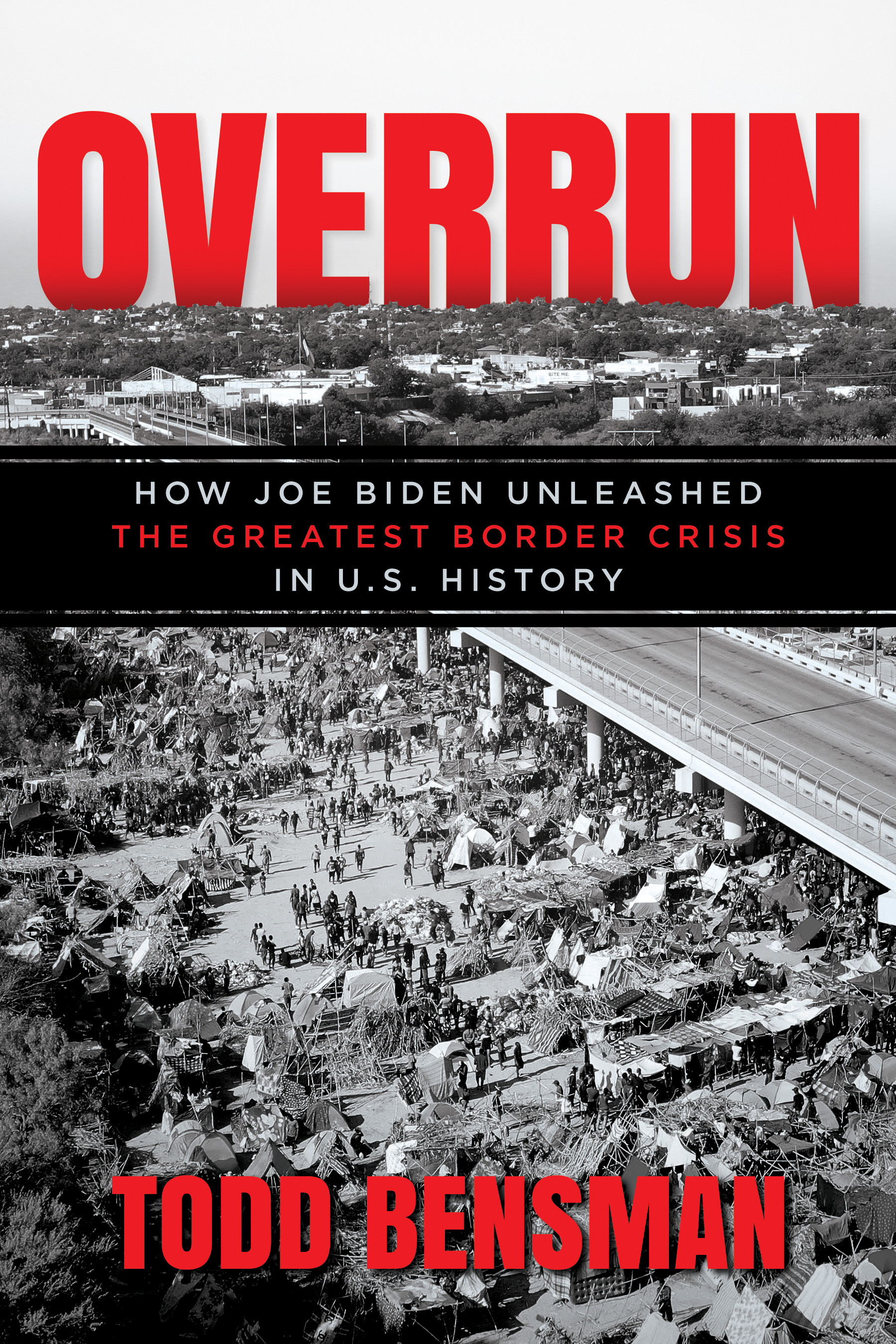

Purchase his book here.

By Todd Bensman on February 25, 2023

Daily Caller, February 25, 2023

The question I am most often asked by interviewers, congressional staffers, and audiences is: what can we do to stop this? My answer is usually not very gratifying, I’m afraid. The puppet strings for the important control of illegal immigration all lead into the White House and, to a limited extent, Congress. Short of any appreciable congressional action, the White House becomes the default location where a mass migration is started and stopped.

American laws already on the books are sufficient to end mass illegal immigration if merely enforced even roughly to their letter, with consistency over time across the entirety of border immigration systems. Because the system was otherwise never really “broken,” “comprehensive immigration reform” of quite sensible immigration enforcement laws was never necessary. The good news is that certain several fixes, combined with that normal enforcement practiced and a slight attitude adjustment, can end the vast numbers of foreign nationals from journeying—and dying on the way.

For starters, as I hope to have proven beyond all reasonable doubt by this point, Democrats and Republicans who do not want mass illegal immigration must run every proposal through this analytical litmus test: Will this or that elevate— or lower—the odds that an aspiring immigrant’s smuggling fee investment pays off with successful entry over the border and long-term legal or illegal stay inside America?

If the policy will increase an immigrant’s entry-and-stay odds high enough, it is the wrong one and should be rejected in any form. Conversely, if the policy will reduce the entry-and-stay odds, it is the right one and should become a candidate for acceptance. This simple calculus, though it may seem obvious, should no longer be allowed to defy broad absorption. If immigrants are telling us that they run this basic calculus through their skein when deciding to stay or go, so too should American leaders. Hear the immigrants.

Beyond that attitudinal adjustment, I offer several recommendations guided by the immigrants’ calculus that are pivotal to permanently ending unwanted mass migrations.

Tear Down and Rebuild the American Asylum System

The United States must withdraw from the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees treaty that President Lyndon Johnson signed in 1968 and rebuild the U.S. asylum system that treaty obliged after Congress incorporated its provisions in the Refugee Act of 1980.

As this book has amply demonstrated in my chapter “Insane Asylum,” no other enticement exerts a greater gravitational pull on illegal immigration than does the easy ability to defraud the American asylum law as it now stands to achieve long-term entry. The asylum system must be torn down and rebuilt because it directly nullifies most congressionally approved immigration statutes that should, if actually executed faithfully, staunch mass illegal immigration.

Center for Immigration Studies Executive Director Mark Krikorian, a prominent proponent of this unconventional idea, calls the treaty an outdated anachronism of the Cold War era that has morphed into a wedge that immigrants and their advocates now mainly use to decide whether they will come in and stay.

“While it is national governments that decide whom to resettle from abroad, foreign intruders are the ones deciding to make an asylum claim, a claim we are bound by treaty to consider and that is subject to litigation in our courts,” Krikorian wrote once in the National Review Online. “Asylum therefore represents a profound surrender of sovereignty, a limitation of the American people’s ability to decide which foreigners get to come here from abroad.”

The time has arrived for this idea to enter into mainstream policy discussion because laws that work at cross-purposes with other laws, as does asylum, constitute an unnecessary tangle that democratic nation-states are not well suited to easily unravel. Nations are allowed to rethink international or binational agreements with other countries. None are permanent marriages where divorce is illegal or too immoral to contemplate. This divorce is necessary.

Until that happens, the threat and probability of mass illegal immigrations will persist. But it may not happen right away; divisions in government may prevent the legislative activity necessary to achieve the outcome even after a UN treaty withdrawal. In the meantime, leadership should feel obliged to reconstitute Trump-era stop-gap policies that, collectively, neutralized the narcotic draw of the asylum system by denying seekers the main motivating benefit: that a claim gets them in to stay permanently win, lose, or abandon. The measures were impactful but not permanent fixes and, as we have seen, reversible by the next White House occupant. While those Band-Aids were better than nothing, the permanent fix to this problem is to eliminate and rebirth an appropriate asylum law.

End the Gold Rush Loopholes

Second only to the asylum law, broad global discovery of the Flores Settlement loophole and the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA) draws in millions of unaccompanied minors and families with children lured by a DHS requirement to quickly release them from detention. Congress needs to sew up both.

As I’ve described at length in this book, TVPRA required the quick release of immigrant kids if they are from noncontiguous countries but quick deportations of Mexicans, so untold thousands of non-Mexicans naturally came when the wider world discovered the law’s almost magical properties in 2014, when Obama was president. Likewise, the Flores loophole as amended in 2015 requires DHS to release children from detention within twenty-one days and allows their parents to go forth with them.

Republicans and Democrats have good reason to join together for these fixes and a logical place to start: the bipartisan Homeland Security Advisory Council’s CBP Families and Children Care Panel Final Report, page two.

In their section on “Interim Emergency Recommendations,” appointees from both parties urged lawmakers to amend the TVPRA to require the same treatment of non-Mexican kids as for Mexican kids, which would then allow for the expedited removal and turn the tractor beam off.

“It is time for Congress to address this issue head on…,” the authors concluded.

As for the Flores loophole, the panel recommended a legislative fix that would lift the twenty-one-day detention limit “to remove any uncertainty and make clear that the Flores restriction on the number of days a [family unit] may be detained has been lifted. Twenty days is insufficient in most cases….” The panel emphasized that it was not recommending indefinite detentions but “believes that DHS and the immigration courts need more flexibility and time to process the unauthorized arrivals than what is currently permitted.”

In the alternative, say a gridlocked Congress, the regulation that Trump wrote is written and waiting. It could be resurrected and put back through the court system until the Supreme Court ultimately upholds it.

A Solution to the Multinational Immigrant Flow and to Protect National Security

As detailed in Part III of this book, the greatest proportion of multinational immigrants in contemporary U.S. history is carrying into the country suspected terrorists and potential war criminals and the spies of adversarial governments. A great many must pass from South America, through Colombia, and into Central America through Panama and Costa Rica. As I reported, all three of those U.S.-allied nations move the migrants northward as a matter of government policy called “Controlled Flow.” This policy has facilitated the movement of migrants out of their territories and into American territory.

The United States should demand that these countries end their controlled flow policies and, in their place, install a U.S.-funded infrastructure in each that would fly all immigrants to origin countries anywhere in the world, on national security grounds.

I’ve demonstrated the awesome deterring power of air repatriation flights, in chapter fourteen’s revelations about the Del Rio migrant camp crisis and in chapter fifteen about the White House insurgency. Panama and Costa Rica happen to be geographically well suited for maximum impact of air-repatriation operations such as these. Panama and Costa Rica are trail-route bottlenecks with oceans on two sides. A series of air operations in these countries should prove especially impactful on downstream motivation to move through the Darien Gap and then toward Mexico.

As a final note, both polling and my own reporting detailing the failed White House rebellion by moderate Democrat advisors demonstrate that this border crisis presents a rare opportunity for both parties to find common ground and equal willingness to fix an obvious homeland security problem. If partisans will divide on just about every other issue, a mass migration emergency of this historic magnitude should stand as one of the few that ought to draw an authentic bipartisan response.