The Texas Observer reported recently that the Biden administration is continuing a policy that he derided as a candidate and purportedly ended (at a huge cost to taxpayers) as president—“family separation” of migrant adults and children who entered as “family units” (FMUs). There is a lot of emotion in that article, but enough facts to get a sense of what’s going on. It all suggests that those separations may be due to miscommunications between agents and leadership, but also likely resulted, at least in part, from legitimate concerns about the welfare of migrant children.

Family Units and the Flores Settlement Agreement. “Family separation” is a novel concept because the entry of adult migrants with children in family units is a relatively new phenomenon.

In fact, Border Patrol only keeps records on FMU apprehensions going back to FY 2013 due to the fact that before 2011, most illegal entrants (more than 90 percent) were single adult males.

That said, however, alien children did enter illegally before FY 2013. To govern the terms of detention and release of minors in immigration custody, DOJ (which had jurisdiction over the former INS) and a class of plaintiffs entered into what is now known as the “Flores settlement agreement” in 1997.

That agreement was “originally applicable only to unaccompanied children” (UACs), as a report from a bipartisan federal panel explained in April 2019.

That changed in August 2015, however, when federal Judge Dolly Gee issued a decision finding that the Flores settlement agreement applied to accompanied children who had entered in “family units”, too, and required DHS to release both the adults and the children in FMUs within 20 days.

The Ninth Circuit later limited the scope of that order to require just the release of children in FMUs, but to avoid “family separation”, the parents and guardians who had brought those children to the United States were and are generally released, as well — even though the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) mandates their detention until they are granted asylum or removed.

Not surprisingly, the number of adults entering illegally with children in the hopes of quick release under Flores soon boomed. In FY 2015, Border Patrol apprehended just fewer than 40,000 migrants at the Southwest border in family units; in FY 2016, after that decision was issued, there were nearly 77,700 such apprehensions.

The inauguration of Donald Trump put a dent in illegal entries across the board, at least initially, with total CBP Southwest border “encounters” dropping 33 percent between FY 2016 and FY 2017.

In the absence of a congressional Flores “fix” and other amendments to close the loopholes encouraging illegal entries, however, apprehensions at the Southwest border soon rose again—with apprehensions of migrants in family units playing a prominent role in that rise.

CBP encounters at the Southwest border increased by just over a quarter between FY 2017 and FY 2018, but Border Patrol apprehensions of FMUs grew almost 42 percent (to 107,212) during that period. The number of FMU apprehensions in FY 2018 was — at that point — the highest in any year for which Border Patrol keeps statistics (again, back to FY 2013).

Illegal Entry Prosecution Pilot Program. From March to November 2017, the Border Patrol ran a pilot program to discourage illegal immigration by increasing the number of aliens criminally prosecuted for illegal entry. Notably, that pilot program allowed for the prosecution of adults who had entered in family units, leading to the separation of some 280 families.

That program was apparently successful, because in El Paso, Texas — one of the pilot’s primary sites— FMU apprehensions reportedly dropped by 64 percent.

“Zero-Tolerance” and “Family Separation”. Thereafter, in early April 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a “Zero-Tolerance Policy for Criminal Illegal Entry”, under which all or most aliens who entered illegally were to be prosecuted under section 275 of the INA.

Those aliens subject to zero-tolerance were passed from DHS to the custody of the U.S. Marshals Service (in DOJ) for prosecution.

Because children are not subject to prosecution for illegal entry — and are not detained in DOJ custody, either— the previously accompanied children in those FMUs became “unaccompanied children” and were sent to Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) shelters under a 2008 law limiting their detention in DHS custody.

The Fallout. Due to public outcry over (and poor implementation of) that zero-tolerance policy, President Trump ended it by executive order (EO) in June 2018. That EO directed the attorney general to seek a modification of the Flores order to allow for the continued detention of family-unit migrants.

The day after that EO was issued, and in accordance therewith, DOJ filed an application for relief from the Flores settlement agreement.

Judge Gee denied that application in July 2018, deriding it as “a cynical attempt, on an ex parte basis, to shift responsibility to the judiciary for over 20 years of congressional inaction and ill-considered executive action that have led to the current stalemate.”

As I noted in July 2018: “The predictable result of that order has been a return to ‘catch and release’, as the New York Times bluntly put it, with the government freeing ‘hundreds of migrant families wearing ankle bracelet monitors into the United States.’”

I continued: “And the predictable result of the end of 'catch and release' will be another influx of . . . family units entering illegally.” I was correct: In FY 2019, Border Patrol apprehended almost 473,700 migrants in family units at the Southwest border, a more than 340 percent increase over the then-record number the year before.

Family separation quickly became a political issue following a Trump administration request for migrant detention funding in mid-2019, as HHS ran out of shelter space and children languished in Border Patrol custody. To say there was a lot more noise than light directed at the issue during that period would be an understatement.

“Family separation” (which, as noted, had ended the previous year) quickly became conflated with images of migrant children in Border Patrol custody and earlier pictures of “kids in cages”. That said, Trump administration messaging failed to clear matters up.

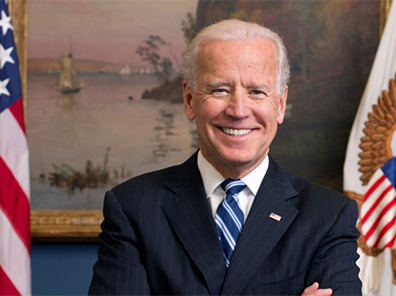

The Biden Campaign. Then-candidate Joe Biden used the conflation of the issues to pummel the then-president, describing it on his campaign website as a “moral failing”:

When children are locked away in overcrowded detention centers and the government seeks to keep them there indefinitely. When our government argues in court against giving those children toothbrushes and soap. When President Trump uses family separation as a weapon against desperate mothers, fathers, and children seeking safety and a better life.

The issue continued throughout the campaign, and during the last presidential debate in October 2020, moderator Kristen Welker brought up the fate of “more than 500 children”, the parents of whom, in Welker’s words “the United States can't locate”. She asked Trump: “So how will these families ever be reunited?” Trump attempted to deflect the issue on the Obama administration, ineffectively.

That task force was directed to reunite families, and according to CBS News in May 2021, plans were in place to start that process by bringing parents — who had apparently already been removed — back to the United States.

Texas Observer. All of which brings me to the rather remarkable recent article in the Texas Observer. According to that outlet, “From the start of the new administration to August 2022—the latest month for which data has been published—U.S. authorities have reported at least 372 cases of family separation”. There are likely other such instances, as the Observer asserts that it “has identified further cases not included in this count”.

Part of that has to do with CDC orders issued under Title 42 of the U.S. Code, which direct the expulsion of illegal entrants to stem the introduction and spread of Covid-19. As amended by the Biden administration, those Title 42 orders excluded children, but not adults.

The Observer reports:

Since the beginning of 2021, Immigrant Defenders Law Center has tracked more than 300 cases of non-parental relatives separated from children at the border. The minors were categorized as unaccompanied and exempt from Title 42, which allowed them to remain in the United States. Their adult guardians were sent to Mexico.

Other grounds for separation cited by the outlet include prosecution of the accompanying adult for illegal entry or reentry (including under 19 U.S.C. § 1459, a customs provision), “health problems, questions about maternity or paternity, or criminal allegations against the parents”.

The latter three were grounds for separating children from adults even under prior to the Trump administration, and each makes sense: Migrant parents are not normally sent for treatment with sick kids (or vice versa); releasing a child when there are questions about familial relationships can lead to trafficking; and accompanying children are not a “free pass” into the country for an adult with a criminal history.

For what it’s worth, a policy that bars prosecutions for illegal entry simply because an adult enters with a child makes that child a pawn in a prosecution-avoidance scheme.

Nonetheless, immigrants’ advocates quoted by the Observer blame either poorly trained Border Patrol agents or, alternatively, what one termed: “A lack of institutional overhaul—both among top-level decision-makers and the bottom-level CBP officials who encounter families at the border”.

Respectfully, “overhauling” the rank-and-file in a law-enforcement component with more than 16,000 trained agents at the Southwest border in the middle of a humanitarian disaster would simply that disaster worse.

As for “top-level decision-makers”, I would note that Biden’s last CBP commissioner, Chris Magnus, was forced out earlier this month, ostensibly for spending too much time attempting to change the agency’s “culture” and too little actually attending to his duties. That said, Magnus’ attempted culture shift apparently had little to do with “family separation”.

In any event, members of Congress should have ample opportunities to question DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas about the family-separation allegations in the Texas Observer article.

Democratic leaders who currently control both houses of Congress, have limited Mayorkas’ appearances on the Hill, but the Republicans, who will take control of the House of Representatives in January, are likely to request his appearance repeatedly in coming months. Even if family separation is not on the agenda, committee chairmen rarely deem non-germane questions out of order.

Ending family separation at the Southwest border was a key priority for Joe Biden. Despite that, the practice apparently continues, albeit at a lower rate than under the Trump administration. That may be due in part to miscommunications between line agents and political decisionmakers, but it’s also likely the result of reasonable concerns about the safety and welfare of migrant children.