In January I analyzed the Biden administration’s plans to alter the terminology used to refer to “aliens”. Those changes are now being imposed on the nation’s 539 immigration judges (IJs) and the 28 members of the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA). It is a problematic move, because their job is to apply the law, and the main word they are now all-but forbidden to use — “alien” — is the law. The courts should really focus on issuing more decisions, a task they are struggling to accomplish.

On July 23, Jean King, Acting Director of the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) — the DOJ entity that oversees the immigration courts and the BIA — issued Policy Memorandum (PM) 21-27. It “directs EOIR staff, including adjudicators, to use language that is ‘consistent with our character as a Nation of opportunity and of welcome.’” [Internal brackets omitted.]

The quote within that quote comes from section 1 of Executive Order (EO) 14012, issued by President Biden on February 2 and captioned “Restoring Faith in Our Legal Immigration Systems and Strengthening Integration and Inclusion Efforts for New Americans”.

If the president truly wanted to “restore faith in our legal immigration systems”, he would start by enforcing the immigration laws at the border and interior of the United States. With the border a chaotic disaster (largely due to Biden’s own policies), and interior enforcement all-but nonexistent (again, thanks to the Biden administration), EO 14012 plainly does not mean what it says.

In any event, as part of the administration’s policy of promoting “opportunity and welcome”, King told the IJs and BIA members that they must use incorrect wording in their decisions. As I will explain below, this is an extremely sinister precedent, but first let me explain how the verbiage has changed.

In lieu of the word “alien”, adjudicators must now use “respondent, applicant, petitioner, beneficiary, migrant, noncitizen, or non-U.S. citizen”. Adjudicators can no longer use the phrase “undocumented alien or illegal alien”; instead, those folks are now “undocumented noncitizens, undocumented non-U.S. citizens, or undocumented individuals”.

The next one gets really complicated. A minor who was heretofore an “unaccompanied alien child” is now an “unaccompanied noncitizen child, unaccompanied non-U.S. citizen child, or UC”.

When I was a schoolboy, I was taught to never use double negatives, but apparently “The Gods of the Copybook Headings” are dead now, too.

None of these changes has any basis in law (or logic for what that matters), as I detailed in that January post. “Noncitizen” is not a word, at least not in a legal sense, because it includes “aliens” (who can be removed from the United States and non-citizen “nationals” (who cannot).

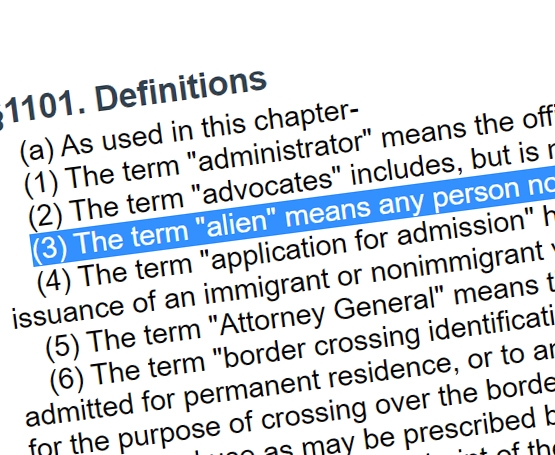

In the "definitions" provision in section 101 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), those distinctions are clearly explained for purposes of applying our immigration laws.

Section 101(a)(3) states: "The term 'alien' means any person not a citizen or national of the United States." Section 101(a)(22) of the INA, in turn, states: "The term 'national of the United States' means: (A) a citizen of the United States, or (B) a person who, though not a citizen of the United States, owes permanent allegiance to the United States."

Referencing a 1998 dissent from the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in a June 2017 post, I analyzed each of these terms and the distinctions between them (and some others to boot), and described how they are used in the law. Simply put, residents of American Samoa and Swains Island are “nationals of the United States” (meaning they cannot be removed under the INA), but they are not “citizens”.

The distinction appears to be lost on King (she does not even mention it, unlike then-Acting DHS Secretary David Pekoske, who kicked off this nomenclature nonsense on January 20), but it is crucial to those American Samoans and Swains Islanders.

The bigger issue, however, is that when it comes to the INA, the now-banned word “alien” is the law. King admitted recognized this fact, circuitously, when she granted adjudicators forbearance in PM 21-27 to use the term "when quoting a statute, regulation, legal opinion, court order, or settlement agreement”. But, if it’s not in quotes, adjudicators better not use it.

In a July 15 post discussing a spat two federal circuit court judges got into over the word, I explained why applying the INA in any given case means interpreting the specific words that are used in the pertinent provisions in the INA itself. Congress conveys its intentions in the law by using specific words, and it is incumbent on adjudicators to assess those intentions by using those words.

Each and every word in the INA has meaning, and it is the job of IJs and BIA members to assess the meaning of any word by using it, and using it correctly. As I explained in a May post, a recent, rather momentous Supreme Court opinion issued hung on the justices’ interpretation of the single indefinite article “a”.

Then, there is the coercion aspect of all of this. IJs and BIA members are lawyers, and the importance of using the correct verbiage in a statute or decision is hammered into you in law school and legal practice.

King is telling those lawyers to do the exact opposite of what they have been taught — and know — is the right thing to do. What sanction awaits the recalcitrant or mossback IJ who transgresses this diktat? Suspension? Dismissal? Those who moaned in the past that Trump administration completion goals undermined the “independence” of IJs should be in high dudgeon now. Where are they?

I speak of all of this from experience, because I was an IJ for eight-plus years. The attorney general gave me his or her discretion (the source of the majority of an IJ’s authority) to make decisions, and the decisions I issued were mine and mine alone.

Now, an unelected bureaucrat is telling my erstwhile colleagues and successors how they are supposed to speak. That is just one small step removed from telling them how to rule, and respectfully, PM 21-27 signals to them which way decisions are supposed to go. Here’s a hint: Ordering an alien removed denies that alien “opportunities” in the United States and is not “welcoming” in the least.

Up to this point, the Biden administration’s adventures in Newspeak have been just so much posturing. Now that it has started changing the meaning of words for legal purposes, however, it has crossed a line that portends much worse.

Then there is the fact that PM 21-27 wastes resources EOIR and the courts just don’t have.

In my last post, I explained how the number of cases IJs have completed has dropped — precipitously — over the last two fiscal years. In FY 2019, they completed nearly 277,000 cases, and even with the COVID pandemic shutting down many courts for more than half of the last fiscal year, IJs still finished more than 231,000 cases in FY 2020. Through the first half of FY 2021, they completed just 43,652, meaning that IJs are on track to complete fewer than 38 percent as many cases this fiscal year as last.

King should be spending more time getting courts open and cases completed, and less time worrying about how judges refer to aliens. She is failing on the first count, and her efforts on the second set a dangerous precedent — for both judicial independence and the rule of law.