Lost amidst the president’s tepid response to the record-high surge of illegal migrants at the Southwest border was one notable CBP crackdown there late last spring — on nonimmigrants crossing to sell plasma at donation centers along the U.S.-Mexico line. That decision may soon have dire consequences for seriously ill individuals and for the pharmaceutical industry. It’s an unusual administration priority.

The Border Plasma Business. Plasma is the component of blood that carries red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets through the body, and constitutes about 55 percent of total blood content.

The fluid plays a critical role in many medical treatments:

Plasma is commonly given to trauma, burn and shock patients, as well as people with severe liver disease or multiple clotting factor deficiencies. It helps boost the patient’s blood volume, which can prevent shock, and helps with blood clotting. Pharmaceutical companies use plasma to make treatments for conditions such as immune deficiencies and bleeding disorders.

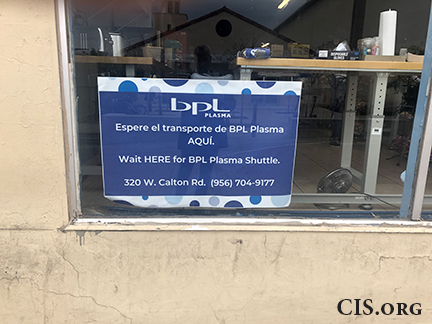

I first became aware of the border plasma industry during a January 2020 trip to Laredo, where I spotted a sign in the window of a shop near the port of entry telling potential donors where to wait for the “Plasma Shuttle” to one of the three donation centers in town.

Since then, I have seen donation centers across the Southwest border (there are apparently many of them), drawing nonimmigrant border crossers from Mexico who can make $40 to $50 a day (and up to $4,000 a year) selling the stuff.

The international plasma industry relies heavily on those border donors, as up to 10 percent of plasma collected in the United States “usually comes from Mexican nationals who enter on visitor visas”, with the United States serving as “the biggest global exporter of blood plasma — a market that reached $21 billion in 2019”.

CBP Crackdown. On June 15, CBP announced that it would no longer allow nonimmigrant visitors on B-1 (business) or B-2 (tourist) visas to sell their plasma in the United States. In a statement released to Breitbart News, the agency explained:

Effective immediately, U.S. Customs and Border Protection advises that donation of plasma for compensation in the U.S. by B1/B2 non-immigrant visa holders is a violation of the terms of their visa and crossing the border for that express purpose will no longer be permitted under any circumstances.

Selling plasma constitutes labor for hire in violation of B-1 non-immigrant status, as both the labor (the taking of the plasma) and accrual of profits would occur in the U.S., with no principal place of business in the foreign country.

While it is permissible to travel on a B-2 visitors’ visa for “medical treatment”, “employment” is barred for nonimmigrants in B1/B2 status. That said, “Visitors for business must be self-supported and may not receive payments for any business conducted, though honoraria may be permitted in certain circumstances.”

There are some rather complicated regulations governing conditions placed on B1/B2 nonimmigrants, but none answers the question of whether aliens admitted under these categories are allowed to sell bodily fluids during trips to this country.

Difference of Opinion on Ethics of Plasma Sales. There is a difference of opinion on the ethics of this cross-border plasma trade.

ProPublica — which cracked the border plasma story in a 2019 exposé with lurid artwork captioned “Pharmaceutical Companies Are Luring Mexicans Across the U.S. Border to Donate Blood Plasma” — contends:

Unlike other nations that limit or forbid paid plasma donations at a high frequency out of concern for donor health and quality control, the U.S. allows companies to pay donors and has comparatively loose standards for monitoring their health.

Donating plasma too frequently can hurt a donor’s immune system. A donor’s level of the antibody immunoglobulin G should be screened every four months under guidelines from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. But in the U.S., donors are still allowed to give plasma up to 104 times a year, far more than in most other countries. Selling plasma has been banned in Mexico since 1987.

The outlet paints a picture of multinational companies operating in a grey area of the immigration laws, and as the foregoing excerpt shows, donors endangering their health to donate in exchange for money that they need to survive. The focus of that piece:

Genesis keeps losing weight, leaving her perilously close to the 110-pound minimum required for donation. To avoid getting turned away at the clinics for being underweight, which has happened in the past, Genesis said she regularly fools the scales by putting water bottles in her pockets.

The Journal, on the other hand, explains that:

Mexican donors say the new visa policy deprives them of income and of pride they took in helping others. And patient-advocacy groups now worry about the availability of plasma-derived medicines, the only treatment for some rare conditions.

Effect on Businesses and the Medical Industry. In that vein (no pun intended) and not surprisingly given the large percentage of cross-border donors, this policy change has had some profound effects on both plasma businesses and the medical industry as a whole.

In November, Australia’s Financial Review detailed the effect of that change on CSL, “Australia’s fourth largest listed company”, which runs 60 collection centers in the four Southwest border states. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, CSL’s outlet just across the Mexican border in Nogales, Ariz., received 4,000 plasma donations a week. Pandemic-related border closures had impacted that supply, and just as those closures began to loosen up, the CBP policy change went into effect.

In October, the company revealed that plasma collections for the 2021 financial year were off by 20 percent, and collection costs had risen, in part because of the new policy (stimulus checks and the upturn in the economy played a role, as well).

In response, CSL will be doing more marketing, opening additional centers, and increasing payments to donors.

More broadly, the Journal details the effects that the limited plasma supply has had on those seeking medical treatments in the United States. Its article focuses on 46-year-old Louisianan Jessica H. Schexnayder who suffers from “multifocal motor neuropathy, an autoimmune disorder that causes weakness in the hands and legs, muscle cramping and fatigue”.

She relies on semi-weekly infusions of immunoglobulin, antibodies that are extracted from plasma.

“Her pharmacy recently warned her there would be a delay in the delivery of the treatment” (it ended up arriving just a day late), but Schexnayder expressed alarm about potential plasma shortages: “I will always have a level of worry about whether or not I can get plasma, just because it’s the only drug that can treat me”.

Industry Response to CBP Plasma Policy Change. The Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease (“an internationally-recognized organization of patients, providers, community organizations, business and labor groups, and health policy experts committed to raising awareness of the number one cause of death, disability, and rising health care costs: chronic disease”) sent DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas a letter in July complaining about the rule change.

It stated:

Given the depressive impact this decision could have on blood plasma supplies and the therapies derived from blood plasma donations, we urge you to reconsider and either withdraw the policy or withhold its implementation to allow for analysis of the health impacts of the decision and consideration of related factors.

More litigiously, plasma companies have sued to challenge the policy change, as CSL has teamed up with its Spanish rival, Grifols SA, to seek injunctions of the policy in federal court in the District of Columbia. The district court dismissed one of those suits for lack of standing in December (the plaintiffs plan to appeal), and so the corporate duo filed a second one that included workers and donors.

Differing Minds Can Disagree. Differing minds can disagree as to whether CBP’s plasma policy is a good policy or a bad one. Both the Center and I oppose any violation of the immigration laws, which are intended — at least in part — to protect the wages and working conditions of similarly situated American workers (both citizens and lawfully admitted immigrants).

It is unclear, however, whether much if any labor is involved in the plasma donation process. If a Mexican national on a B-2 visa were to drive his or her own car to Laredo, nothing that I am aware of would prevent that individual from selling the car, pocketing the proceeds, and walking back south.

Both one’s car and one’s plasma are real property, so I am a little unclear how selling your Buick is not a violation of the immigration laws, while selling your vital fluids would be. Perhaps the plasma donor is akin to a car dealer in CBP’s collective imagination, however, a scenario that would change the facts of the matter.

Further, I am not a medical professional, so I don’t know whether comparably lax U.S. limits on the frequency of plasma donations pose a health risk or not. That health risk would apply equally to a U.S. citizen who donates as often as possible in Gastonia, N.C., and a Mexican national who crosses over and does the same in El Paso, Texas, however, and nobody is changing those donation rules.

This does seem to be an odd place for CBP to be taking a border stand, though.

Border Patrol agents apprehended nearly 5,763 illegal migrants per day at the Southwest border in June. Rather than crafting policies to deter their illicit entry, CBP was busy barring otherwise legal Mexican border crossers from donating plasma — a desperately needed therapeutic — for $40 a pop. Even if the plasma rule is a good one, curbing illegal immigration is much more critical to our national security.