Topic Page: Covid-19 and Immigration

- The city of Laredo, Texas, is ordering its residents to wear face coverings when they enter a building, public transit, or outdoor gas station.

- The order is in response to concerns that Mexico, across the Rio Grande, is not doing enough to respond to the Wuhan virus.

- Concerns have spread across media sources that Mexico has failed to take sufficient and timely steps to stem the spread of the virus, and could face a health disaster that would swamp the country's medical resources.

- If Mexico sees a major outbreak of the Wuhan virus, strict border controls the administration has put into place may need to be tightened even more.

On Friday, the Washington Post reported that the city of Laredo, Texas, is ordering all of its residents to wear face coverings, or face a $1,000 fine. Note that although the Post calls it a "mask ordinance", any kind of face covering will do — "a bandana, a scarf or even a spare piece of fabric as long as it covers the[] nose and mouth". The rule applies to "anyone [who] enters a building, public transit or outdoor gas station". The Post article, which contains some interesting statistics and perspectives, is a revealing look into how the Wuhan virus could affect the Southwest border in the months to come.

That article states that, as of Thursday night, 65 Laredoans had tested positive for the virus, and five have died of it. The Census Bureau's latest statistics (from July 1, 2018) show that there were then an estimated 261,639 residents in the city, meaning that the rate of infection is 0.02 percent, but the mortality rate is 7.7 percent for those infected.

By comparison, Washington, D.C., reports (as of Thursday) that there were 757 virus cases in the city, but only 15 deaths. The Census Bureau estimates that there were 705,749 DC residents as of July 1, 2019, an infection rate of 0.1 percent, but a mortality rate of just less than 2 percent.

It would be difficult to conceive of two more vastly different cities, or metropolitan areas.

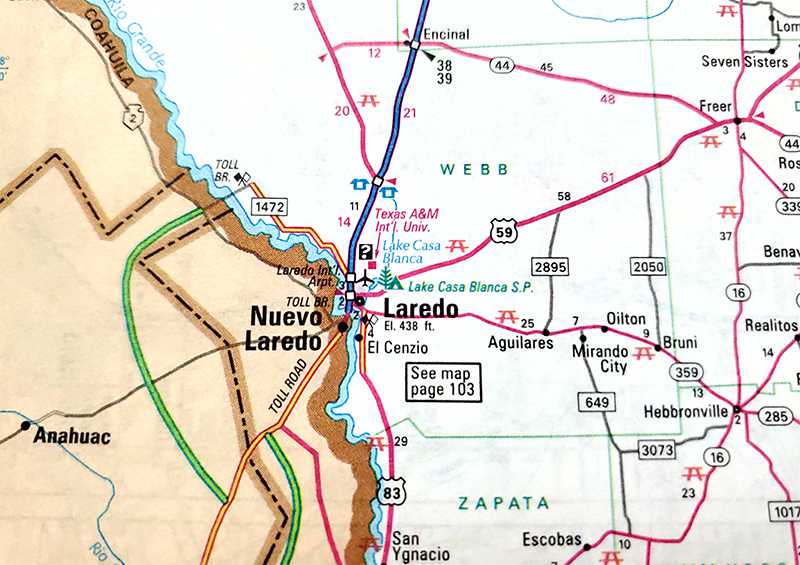

Laredo has a land area of 88.91 square miles, with one large neighbor (Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico — population 397,100 as of 2014, but likely larger now), but is relatively isolated otherwise. Much of the city of Laredo is spread out, with only a concentrated population downtown, directly near the river and the non-commercial ports of entry.

Washington's 700,000-plus residents, on the other hand, live within a slightly smaller 61.05-square mile enclave of fairly densely populated neighborhoods, and are surrounded by massive suburbs on every side (the business there is government, and business is always good).

There are two important factors that, I would posit, have contributed to the lower rate of reported illnesses in Laredo as compared to Washington, D.C.

First, Laredo has three hospitals (one strictly for long-term acute care) and a rehabilitation center, with a total of 549 beds. More than 30 percent of the residents of Laredo under the age of 65 have no health Insurance.

Washington, D.C., on the other hand, has six hospitals (three of which are associated with universities) with 2,156 staffed beds, and the greater metropolitan area has several more. In fact, Washingtonian Magazine boasted in 2017 that the "Washington Area Is Home to 11 of [the] Country's Best Hospitals, According to US News", but that admittedly included UVA Hospital about 100 miles the south, and Johns Hopkins Hospital about 35 miles to the north. Significantly, only 3.2 percent of Washingtonians had no health Insurance in 2018, the second lowest rate in the nation.

Second, the official poverty rate in Washington, D.C. , is 17.4 percent and the median household income is over $85,000. The poverty rate in Laredo, on the other hand, is 30.6 percent, and the median household income is $39,408 a year, well below the national average of $53,482 a year.

Health care is well outside of my skill set, but as KFF explains (logically): "Uninsured people are far more likely than those with insurance to postpone health care or forgo it altogether." And it has been my experience that the less money I had in my pocket, the less likely I was to seek medical attention — health insurance or not. Even with the best federal health plans, copays add up.

If I had to make a guess, therefore, many more residents of Laredo don't seek medical assistance except for extreme conditions, and therefore fewer have been tested (and consequently tested positive) for the Wuhan virus.

That would (all other things being equal) explain the difference in mortality percentage rates between Laredo and Washington, and suggest that the actual rate in Laredo is higher than the official statistics would suggest. The face covering order itself also suggests that the government of Laredo has similar concerns, but that is not the only one they have — nor the official one.

The Post reports: "Many fear that the numbers [of those testing positive for the virus] could grow much higher, given Laredo's proximity to a major international border crossing" — Nuevo Laredo. More specifically, Laredo City Councilman George Altgelt, during a special session on Tuesday, stated: "We're next-door neighbors to a country that's not even taking this seriously" — Mexico.

The U.S. Embassy in Mexico City states that as of April 1, the country had 1,378 confirmed cases of the virus (just 20 more than Mississippi). And Mexico currently has measures in place to stem an influx of cases from abroad, as well as to limit community spread. It has closed its schools until April 30, and suspended "non-essential activities in the public, private, and social sectors" as well as "meetings of 100 participants or greater", for example.

That said, however, an April 3 Forbes piece by Nathaniel Parish Flannery was pointedly critical of Mexico's response to the virus. In an excerpt that is indicative of the piece as a whole, he states: "Unfortunately, Mexico still seems woefully unprepared."

Flannery's aim was particularly (but not exclusively) directed at Mexico's president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (popularly known as "AMLO"), asserting AMLO "doesn't seem ready to acknowledge that for better or worse, his response to the coronavirus pandemic will define his legacy."

The author quotes Mexico City-based health-policy consultant Xavier Tello:

"We aren't prepared. Today we are short on products and space in hospitals. When the numbers of patients grow we won't have protective equipment. Doctors will get sick. We'll have problems because the number of patients will exceed the capacity of our hospitals. They'll get swamped."

Flannery cites many reasons for Mexico's lack of preparedness, including its shortage of tax revenue, the inequality and informality of its economy ("half the labor force works off-the-books and don't pay taxes"), and the rhetoric and messaging of AMLO himself.

Flannery is not alone. From Brookings on March 30: "AMLO's feeble response to COVID-19 in Mexico". Bloomberg on March 28: "Hugs, Kisses, Dining Out During Virus Raise Fear in Mexico" (section header: "Late, Wrong and Slow"). Vox the same day: "Mexico's coronavirus-skeptical president is setting up his country for a health crisis, Some doctors say Mexico could become the new Italy — or worse". Human Rights Watch on March 26: "Mexico: Mexicans Need Accurate COVID-19 Information, López Obrador Misinforms Public on the Health Risks of the Pandemic". The Hill on March 19: "The Mexican government's response to COVID-19 is insufficient".

Perhaps, like Sweden, Mexico will go its own way in response to the virus and (in the short-term at least) be relatively unaffected.

The Scandinavian kingdom, with a population just short of 10.1 million, has minimal restrictions in place but had just 4,947 virus cases and 239 deaths as of March 31. Portugal, by comparison, with a population just less than 100,000 than Sweden, has significant restrictions (a state of emergency with random checks on roads, highways, and bridges; bans on gatherings larger than five; closed borders, etc.), and had 7,443 cases on the same date, and 209 have died from the virus there thus far.

That said, maybe Mexico will not be so lucky (and perhaps Sweden's relative good fortune will change — they had 2.3 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants in 2017, the United States has 2.8, while Mexico has just 1.5).

If that happens, and the virus rages through our neighbor to the south, even the administration's current strict Southwest border policies will likely be tightened even more. Judging from the actions of the Laredo City Council (which is more conscious of conditions across the Rio Grande than most), they believe that, as it relates to the Wuhan virus, the worst in Mexico is yet to come — and will be bad, indeed.