Download a pdf of this Memorandum

Updated July 27, 2011

David North is a CIS fellow who has studied the interaction of immigration and income transfer programs for more than 30 years.

Summary: While the immigration policy debate usually discusses amnesty or legalization programs in black-and-white terms, in reality there are numerous existing quasi-amnesties for subsets of aliens; this report focuses on four of them, all complex, all partial, three fully active and one partially so, and all providing significant economic benefits to aliens other than green card holders.

When the general public thinks about illegal aliens, it does so in terms of deportation, on one hand, and a “path to citizenship” on the other, and very little about government actions that fall between those two extremes.

There are, however, a variety of quasi-amnesties,1 rarely discussed as a group, with each providing non-green card carrying aliens with one or more benefits. These programs overlap each other, provide different kinds of economic benefits, reach different populations, change their own rules from time to time, and are a constant reminder of the needless complexities of our on-the-ground immigration policies. In some cases an alien can wrangle himself legitimate access to one or another of these programs, and in other cases the programs are, because of their complexities, subject to alien abuse.

The quasi-amnesties examined in this report have all resulted from group decisions of one kind or another, and are not created as a by-product of a judicial or semi-judicial process. As this is written, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is being reported in the New York Times as engaged in a further easing of the deportation process, giving ICE agents more authority, on a case-by-case basis, to defer or cancel individual removals.2 This action is, of course, troublesome and has some similarities to the quasi-amnesties of interest, but is outside the scope of this paper.

This, then, is an initial examination of a collection of immigration-related programs that, to our knowledge, has never been examined as a group.

This may well become a rather more prominent field than it is now, because the Obama administration, thwarted by congressional disinterest in “comprehensive immigration reform,” may turn to administrative means to reach some of its pro-migration goals. And, as I point out below, the administration has taken several small and large steps along this path in the last two years.

For ease of presentation we focus on four of the existing or recent quasi-amnesties:

PRUCOL (Permanent Resident Under Color of Law). Formerly a larger program than it is now, it currently applies to new applicants for state-funded welfare programs in New York, California, and several other states, but not to the U.S.-funded versions of the same programs. These are state versions of programs that are much like the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Medicaid programs. A shadow of PRUCOL continues to govern the eligibility of a dwindling group of persons who were drawing benefits from federal assistance programs when the law was changed in 1996. For them, PRUCOL was grandfathered.

TPS (Temporary Protected Status). Grants legal presence in the United States and legal access to the labor market to illegals from specified nations determined by the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). The only TPS program open for new enrolments at the moment applies to people from Haiti. While the program carries the name “temporary,” in practice its coverage of previously enrolled persons is routinely extended year after year. Many of the Central American migrants in the country currently have this status.

EAD (Employment Authorization Documents). Another DHS program, it applies to a wide range of illegal (and not so illegal) aliens, allowing them to work legally in the United States for limited lengths of time.

Qualified Alien. Fairly narrowly defined groups of aliens (much less numerous than those in the old PRUCOL programs) can use this vehicle to secure federally funded SSI, Medicaid, and SNAP (Food Stamps) programs. These programs are administered by the Social Security Administration and the Departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture, respectively.

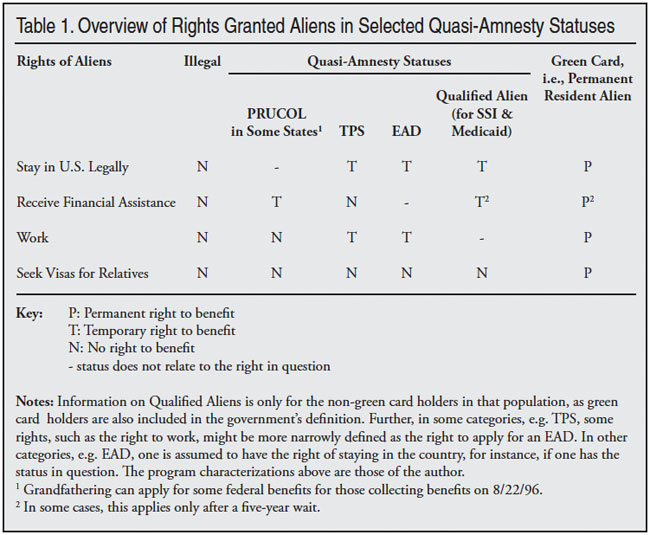

For a rough summary of these four programs and their functions, see Table 1, “Overview of Rights Granted Aliens in Selected Quasi-Amnesty Statuses.”

Background

These programs were usually developed separately and do not necessarily connect with each other. But all have several elements in common:

- all are based on class or group actions, and none stem directly from case-by-case judicial processes;

- all relate to members of migrant populations who have something less than green cards;

- each provides an economic benefit of some kind, often temporarily;

- a great deal of overlap exists among the populations covered by these programs;

- substantial differences in program coverage exist, and there are apparent inconsistencies

- most of these rules seem to have been written from the point of view of an economic program, rather than an immigration program, and

- none of the programs appear to be transitory schemes, as steps toward a comprehensive immigration reform, for instance; each seems to be a permanent set of arrangements for often transient

populations.

Further, in general terms, with the exception of the “Qualified Alien” category, these programs all seem to be written to extend the government’s social safety net a little further toward groups on the edge of full legal status, and to soften welfare reform efforts that might appear to be harmful to certain marginal groups, such as older immigrants who have not yet — and may never — obtain either green card or citizen status.

On the other hand, in recent years these provisions have become considerably tighter and more carefully defined than in the past. The watershed moment came with the passage of welfare reform in 1996,3 when many new requirements were laid on low-income people in the United States generally. Among its provisions was an elimination, for most new applicants to federal programs, of the PRUCOL eligibility that had been in effect for the SSI and Medicaid programs.4

A more detailed discussion of each of the four programs follows, in the order shown in Table 1, as does a note on what is known or can be estimated about the size of these populations. In addition, there is a summary of seven relatively small quasi-amnesties that have been created in the last two years by the current administration.

Continuing Role of PRUCOL

The messiness of America’s immigration systems is nowhere so well illustrated as it is in the field of PRUCOL, a program that is now much smaller than in the past.

Given the pressures to extend benefits to certain classes of apparently worthy aliens who were not in permanent resident alien (PRA) status, one might think that the immigration system would define such persons, by law or regulation. Once that system had determined who belonged in this category, it would issue documents identifying such persons.

That did not happen. What did happen was the federal courts5 determined in 1979 that it was legal to provide welfare benefits to illegal aliens whom the U.S. government did not want to deport. They were determined to be Permanent Residents Under the Color Of Law (PRUCOL) and the concept found its way into both statutes for, and regulations of, various benefit-granting organizations. These agencies then issued elaborate rules for how welfare workers were supposed to sort through a huge variety of immigration control documents to figure out who was a PRUCOL alien, and who was not.

It was an Alice in Wonderland situation in which non-immigration agencies made determinations about immigration status.

One useful listing6 of classes of aliens within the PRUCOL scheme shows 18 different scenarios that could lead to that status, in this case relating specifically to the receipt of Supplemental Security Insurance (SSI) benefits. These classes include some obvious groupings, such as refugees and asylees, and people who were still waiting for legalization under the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. The listing also includes, among others, the following classes of illegal aliens, all of whom had been found deportable, but had not been deported, and whom the government had no plans to actually deport:

- “Aliens residing in the U.S. pursuant to an order of Supervision under section 242 of the INA;”

- “Aliens residing in the U.S. pursuant to an indefinite stay of deportation;”

- “Aliens residing in the U.S. pursuant to an indefinite voluntary departure;”

- “Aliens granted stays of deportation by court order, statute or regulation;”

- “Aliens granted deferred action … whose departure INS does not contemplate enforcing;” and

- “Aliens granted deferred action status pursuant to INS operating instructions.”

Note the large number of arrangements possible for the non-deportation of the deportable.

Several of the subclasses shown above, by definition, include people that the immigration judges have ordered to leave the country, but ICE has decided can stay, a population discussed more thoroughly in Judge Mark H. Metcalf’s recently published CIS Backgrounder “Built to Fail: Deception and Disorder in America’s Immigration Courts.”7

In these specific instances, before the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, these court-ordered deportees not only could stay in the United States, but they could, if otherwise eligible, collect welfare benefits, and as noted later, could legally obtain jobs.

PRUCOL, however, is currently but a shadow of its former self. There are only two populations for which its rules now apply.

The lesser of the two, and shrinking steadily with deaths, are those grandfathered beneficiaries of federal SSI and Medicaid who were drawing benefits in 1996, and who are: a) still alive, b) still eligible for those benefits, c) still in the United States, and d) have not secured PRA status. These individuals are now in the “Qualified Alien” category to be discussed subsequently.

The more significant population consists of those in PRUCOL status who are eligible for state-funded SSI and Medicaid programs and who live in the minority of states that permit benefits to go to this population. These programs are often considerably less generous than the versions of them that have federal funds. California and New York State are the major players but there are other states as well.8

The previously cited Social Security document9 had four lines in an eight-page document listing groups of aliens not covered by PRUCOL. They are: “nonimmigrant aliens,10 aliens statutorily prohibited from being in PRUCOL, and applicants for a status other than applications listed [in that document].”

Temporary Protected Status

While PRUCOL aliens come from all over the world, and in a wide variety of immigration situations, the arrangement is a little less complex with TPS. This population consists of illegal aliens from specific nations who have signed up for TPS status, which gives them legal presence for a stated length of time, and allows them to apply for EADs. (A small minority of people with TPS status also can hold, at the same time, a short-term legal nonimmigrant status such as being an F-1 foreign student. They have the attractive option of using whichever of these statuses suits them best.)11

TPS is a status that can be, and has been, granted by the unilateral decision of the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security.12 The designations have always been country-specific and typically apply to all illegal aliens from the named nation that are in the United States as of a specific date.

Illegals from six nations currently have TPS status as follows:

| Nation | Applicant Must Have Been Resident in the U.S. Since: |

| Honduras | January 5, 1999 |

| Nicaragua | January 5, 1999 |

| El Salvador | March 9, 2001 |

| Somalia | September 4, 2001 |

| Sudan | October 7, 2004 |

| Haiti | January 12, 2011 |

An alien who potentially qualifies must sign up for the program. Initial application periods have been closed for years for the first five nations, but will remain open for Haitian illegals until November 15, 2011.

While each of these TPS statuses has an expiration date, or “current expiration date” as a recent United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) document13 puts it more accurately, these dates are extended time after time, so that a Honduran, for instance, who first secured TPS status in 1999 now has held it for more than 12 years, and may be able to do so for the rest of his life. Thus each TPS population is aging in place.

TPS has never been terminated for a Western Hemisphere population, but short-term TPS has been provided briefly to several small Eastern Hemisphere populations and then terminated. This was done for people from Angola, Bosnia-Herzogovina, Burundi, the Kosovo province of Serbia, Kuwait, Lebanon, Liberia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. In the case of Liberia, the United States terminated TPS in 2007 but simultaneously created Deferred Enforced Departure (DED), which gave the 3,600 Liberians involved the same sets of rights that they had earlier. That status will expire on September 30, 2011, but it is sure to be extended.14

While TPS status allows its beneficiaries to obtain the EAD, and thus legal U.S. jobs, it does not allow them to obtain welfare benefits.

TPS is not available to aliens from countries not listed by DHS, nor is it available to aliens from those countries except in specified time frames.

DHS has published workload data on the number of approvals for initial and renewed status in this program, and the number of approvals, but not the number of denials, so the number of non-approvals consists, irritatingly, of both denials and not yet-acted upon applications. As with most USCIS programs, there are relatively few cases in the latter category, there being 2,011,420 applications and 1,759,378 approvals in the fiscal years 2001 through 2010. So there is a 12.5 percent incidence of denials and delayed decisions15 over this period.

Employment Authorization Document

The EAD program is designed for a middling group of aliens.

While some aliens cannot get the EAD under any circumstance (those who “enter without inspection” and tourists, for instance), and some aliens do not need EADs because they are members of a class of authorized workers (PRAs, diplomats, workers on H visas etc.), there is a third group that falls in between.

These aliens belong to one of the numerous classes of aliens who, as groups, do not have the right to work, but as individuals they may qualify to work, so individual decision-making is needed, hence the EAD.

For example, TPS aliens and spouses of J-1 (exchange program) aliens may work if they successfully apply for an EAD, but not otherwise.

I have no basic objection to the existence of the program, but I do have some worries about how far it has been extended, particularly to aliens who are within the deportation process, but not yet deported.

This brings us to the question: Just who is eligible for an EAD?

The answer is many, many quite different groups of aliens, some tiny and some large, some bland and some questionable. The latest set of instructions16 for filing the USCIS Form I-765, “Application for Employment Authorization,” lists 44 different categories, and there is, in addition, a small, exotic 45th category that we will get to later.

In the small and bland categories are the dependents of various diplomats and international agency officials, i.e. people carrying A, G, or NATO visas. There is even a special category for the dozen or so dependents of Taiwanese diplomats, reflecting the fact that we do not recognize that island diplomatically, but we do, in fact, have its diplomats, and their dependents, in the United States (Taiwanese diplomats, unlike other diplomats, do not carry A visas.)

Similarly, there is a category for spouses of E-2 CNMI (Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands) investors, a tiny and probably shrinking population.

Larger and perhaps inevitable groups include F-1 students wanting off-campus jobs, refugees, asylees, and some asylum applicants, as well as TPS aliens.

A questionable group, in my eyes at least, consists of the spouses of L-1 intra-company transferees, who for some reason, are treated differently than the spouses of H-1B workers, who, as H-4s, cannot apply for the EAD. Since there are many multinational corporations that can use either H-1B or L-1 workers, and since the labor market rules for L-1 visas are even skimpier than those for H-1Bs, many corporations prefer the L-1 visa to the H-1B; so why make the L-1 visa even more attractive to these incoming workers, and thus to their employers?

Even more questionable are the four categories of aliens previously ruled deportable but who, with an EAD, can now work legally. These categories, using the words of the I-765 application, are for those with:

- “Final order of deportation;”

- “Granted withholding of deportation or removal;”

- “Applicant for suspension of deportation;” and

- “Deferred action.”

The irony is that the alien prior to his or her involvement in the deportation process could not secure an EAD, but now that the alien is in one of these near-deportation statuses, the EAD is legally available. One wonders if an alien, or an alien’s clever attorney, could initiate such a near-deportation status with the goal of securing an EAD?

That possibility to the side, why encourage deportable people to stick around by letting them work?

What might be regarded as the 45th category of potential EAD holders is a tiny one and offers no threat to the U.S. labor market, because of the small number of people involved. Further, they will presumably not cluster in any particular sector of the labor market. Geographically, however, they are likely to be in Washington and near the UN in New York. The existence of this category or subcategory does raise some questions, however, about how these decisions are made.

There has always been a group of dependents of foreign diplomats who may seek an EAD if they want one. What the State Department did was to redefine “dependent” so that term is no longer restricted to the diplomat’s family members; it now includes members of his or her household, as well. Thus covering live-in lovers of both sexes.17

So now not only family members of diplomats can get EADs, so can unrelated people living with the diplomats.

Subsequently, using yet another bureaucratic maneuver, the State Department added a new category in the J-1 Exchange Visitor program to accommodate live-in, same-sex lovers of returning American diplomats, but that is outside the EAD program.18

I have nothing against same-sex marriages and other similar arrangements but find it distressing that the only same-sex relationship that can lead to legal admission to the United States, and to legal jobs, is confined to partners of diplomats.

Another long-continuing category among those who can apply for an EAD looks suspiciously like a boon for diplomats returning from overseas with servants hired abroad; it is for nonimmigrant domestic servants of a U.S. citizen. The I-765 instructions say that an applicant for this status must show “evidence that your employer has a permanent home abroad or is stationed outside the United States and is temporarily visiting the United States or the citizen’s current assignment in the United States will not be longer than four years.” (Emphasis added).

That sounds like an arrangement for an American diplomat being rotated back to the United States for a tour of duty at the State Department.

These last mentioned categories, for servants of, and same-sex partners of, diplomats reflect some of the narrow priorities that go into the creation of these quasi-amnesties generally.

The EAD program, incidentally, is another DHS-operated program, like TPS and it, too, generates a document that shows that one is, in fact, authorized to work in the United States. It, like TPS, and unlike any version of the PRUCOL program, is accompanied by a fee. That is $380 for EAD itself. The fees for TPS are $50 for the application and $85 for biometrics (including fingerprinting), so the whole cost of the three comes to $515 for a new TPS-EAD applicant.

A few categories of EADs, such as those issued to citizens of the three former de facto U.S. island colonies in the central Pacific, do not have fees attached.19 Similarly, there are no fees for refugees, asylees, or for household members and other dependents of diplomats and international civil servants.

Since EADs are temporary in nature, they often need renewal. This, in turn, generates fees for DHS. I suspect that the renewal of a previously issued EAD is not a very time- or attention-consuming process.

USCIS is even more generous in its EAD decisionmaking than in the TPS decisions, and it makes available, again, only the numbers of applications filed (some 15,776,000 over the last 10 fiscal years) and approvals in the same time frame (14,502,000). This produces a denied-or-not-yet-acted-upon percentage of 8.1 percent, and an approval rate of 91.9 percent.20

Qualified Aliens

While the previous three categories — PRUCOL, TPS, and EADs — were all introduced and nourished to expand benefits to non-PRA alien populations, the concept of Qualified Aliens was aimed in the opposite direction, toward restricting those benefits. Nevertheless it remains an appropriate member of this set of four quasi-amnesty concepts, because, to some limited extent, it makes benefits available to a small group of aliens who lack green cards.

When I first paid attention to the interaction of immigration and income transfer programs some 30 years ago, there were patterns, particularly related to Korea and Turkey, of former residents of those countries bringing their aging parents to this country quite specifically so that they could get SSI benefits, and obtaining them right after arrival. This is no longer the case, or nowhere nearly as obvious, partially because of the creation of the Qualified Alien category.

This category is a highly restricted, post-1996 Welfare Reform Act listing of aliens who are permitted to receive federal assistance payments, such as SSI, Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, the old AFDC program) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, the old Food Stamps program).

The concept of Qualified Alien thus largely replaced the much more generous ones of PRUCOL. While the rules do not seem to be exactly the same for the four federal assistance programs, most are shaped like those of SSI, which are described below.

As Jill D. Moore, a University of North Carolina professor, has described it,21 the definition of “Qualified Alien” (note this cheerful, positive term adopted by the Congress) emerged from a multi-step process on Capitol Hill.

First, Congress passed the Welfare Reform Act of 1996, which substantially reduced aliens’ access to tax-funded benefits, both for PRAs and for others. Later, four more laws were passed: the Immigration Reform Act of 1996, the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the Agriculture Act of 1998, and the Welfare Reform Technical Corrections Act of 1998. Each of these contained broadening amendments to the Welfare Reform Act, bringing more benefits to more aliens. Without examining these legislative comings and goings, or dealing with the limits on benefits for PRAs, let’s turn to how the SSI rules, for non-PRAs, currently operate.

In addition to a sizeable group of PRAs, there are seven broad sets of non-green card holders that may qualify for SSI benefits,22 they include:

- some section 207 refugees;

- some section 208 asylees;

- some illegals with deportation withheld under section 243(h) of the INA;

- some conditional entrants;

- some parolees;

- some Cuban-Haitian Entrants (a formal term which does not include all Cubans and Haitians); and

- some battered spouses

The operative word here is “some.” Let’s take the battered spouses, whose eligibility is limited in the same way as all are in the last five of the seven classes. To be eligible for SSI benefits the spouse would need to be battered and either “a veteran, active duty member of the U.S. military or a spouse or dependent child of a veteran or member of the U.S. military or lawfully residing in the U.S. on 8/22/96 and blind or disabled or lawfully residing in the U.S. and was receiving SSI on 8/22/96.”

There may well be battered spouses who qualify as vets, or as being either blind or disabled 15 years ago, or collecting SSI 15 years ago, but their numbers must be minuscule.

Bear in mind that receiving SSI benefits for the aging starts at age 65, (and most alien SSI beneficiaries in 1996 were in that category rather than in the disabled one); that would mean that they would have to be at least 80 today to eligible under that section of the rules.

I was unable to find a definition of “lawfully residing in the U.S. on 8/22/96,” but given the context I suspect that it is the grandfathering of the PRUCOL status.

Looking at some of the other seven classes, both conditional entrants and Cuban-Haitian Entrants relate to long disused elements of the INA, and the illegals whose deportation had been withheld under the cited section of the law had to be ruled in danger of death or serious persecution were they to be sent back to their home countries, a rarely-invoked provision. All of the aliens in four of these five last listed classes then also had to qualify under one of the three provisions cited for the battered spouses. In the fifth case, that of parolees, the text of the cited Social Security document is confusing as it may include an editing error.

In short, these groupings are very, very small populations.

The provisions are more generous for refugees and asylees. If they do not qualify under the three restrictive requirements described they can receive benefits, but only for nine years. Pending legislation would extend the cut-off date. Further, any sensible refugee or asylee would move quickly to PRA status as soon as they are eligible.

In addition to all the restrictions described above, there is a general (but not universal) provision that many PRAs and other qualified aliens must wait for five years after arrival in this country to collect benefits.

There seem to be no fees charged in connection with Qualified Alien status.

The changes in SSI eligibility for aliens, reflected in the substitution of the Qualified Alien class for the older PRUCOL class, has caused a dramatic reduction in the incidence of alien collection of SSI benefits, as spelled out later in this report.

Obama’s Quasi-Amnesty Programs

One concern is that, given the slim chances for any legislative action on comprehensive immigration reform, the Obama administration might take administrative action to extend the already existing quasi-amnesty programs still further. Or create brand new ones. In that regard it is useful to review what the administration has done along these lines in the last two and a half years.

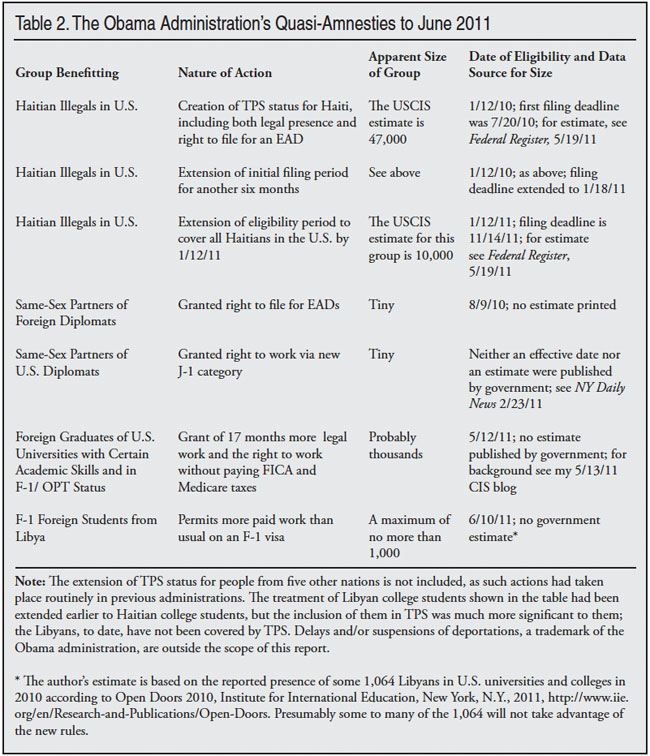

Definitions are at play here, but by my count there have been at least seven quasi-amnesties during this period: three relating to Haitians, two for same-sex diplomatic couples, and two for different groups of foreign college students. These are all administrative actions that have given legal status or economic benefits (or both) to non-green card carrying aliens. (As noted earlier, different kinds of administrative decisions, such as those postponing or blocking law enforcement actions such as deportations, are outside the scope of this paper, but there have been plenty of them.)

The seven quasi-amnesty actions taken so far by this administration are listed in Table 2. In each of them the administration acted without congressional involvement.

Haitians. At the time of the disastrous Haitian earthquake in January 2010, the administration took several actions to avoid what it considered unhelpful immigration policy-related impacts on that nation. A totally non-objectionable one, from my point of view, was to delay deporting Haitians back to their home country until conditions there improved. I do not regard that as a partial amnesty. After a while the deportations were, in fact, renewed, but in small numbers.

The administration also took a more drastic step: It decided that all Haitian illegals in this nation should be granted Temporary Protected Status, and thus saw to it that no one in TPS status would be sent back to that unhappy nation. Every Haitian who was in the United States in legal or illegal immigration status on the day of the earthquake was made eligible for at least temporary legal status. Those eligible were to sign up by July 20, 2010.

USCIS expected 150,000 or so applications. The agency pulled out all the stops to make the process an easy one, deciding, for instance, that there was no need for face-to-face interviews with every applicant. It reached out extensively to the Haitian community and, knowing it was a low-income population, publicized the availability of waivers for the fees, and even changed the fee-waiver process to make it easier for the applicants.23

The turnout was disappointing, apparently, to the agency, and so it extended the registration period, but not the eligibility period, extending the former for more than six months. By the end of this second round of applications, the USCIS said that there were only 47,000 approvals.24

The third amnesty-like action came in May 2011, when USCIS decided to extend both the eligibility period and the application period. The latest set of rules, announced on May 19, 2011, let any Haitian apply who was in the nation on January 12, 2011, a year after the earthquake, and allowed registration to continue until November 14, 2011.

Why so few applications? There are several possibilities, one of which is that there were not as many Haitian illegals in the country as the agency expected. Another is that the fees were daunting, and I think that must have been significant. A third, which came out at some of the stakeholder meetings called by USCIS, was that many eligible Haitians worried that if they came forward they would be identified for deportation in the future.

USCIS was in a bind on that one — it could not tell the potential applicants what everyone in the immigration business knows — that there is nothing so permanent as Temporary Protected Status.25

Same-Sex Diplomatic Couples. The two separate actions, first for partners of foreign diplomats, and later for partners of our own diplomats on U.S. assignments, have already been described.

Foreign (F-1) Students. There were two quite separate actions in this regard, one presumably taken on State Department initiative and totally understandable, and another, taken by DHS alone, that I regard as deplorable.

The State Department must have played a role in the decision (formally made by ICE) to allow Libyan students to get EADs for longer hours of paid employment than they normally could have had with their F-1 visas. The basic notion (not quite stated this way) was that with the U.S. bombing their home country these students might be getting less financial support from their parents than usual, hence they should be allowed to seek additional employment.26 Similar arrangements have been made in the last two years about Haitian F-1 students, but since these students were also covered by the much more sweeping provisions of TPS, I did not define those minor F-1 actions as constituting a separate quasi-amnesty.

More significantly, the Department of Homeland Security, earlier in the year, made a little-noticed decision27 to give thousands of F-1 graduates of U.S. colleges and universities a remarkable advantage over U.S. college graduates in the same disciplines.

Employers were, in effect, granted as much as $10,000 each in bonuses if they hired an F-1 graduate in, say, Animal Industries, or in Management Science, rather than a permanent resident alien or citizen graduate in the same field. The financial break comes because such employers were given 29 months of freedom from having to pay the usual payroll taxes for such workers.

Further the F-1 graduates were granted not only these months without paying their part of the FICA and Medicare taxes, they were also given an extra 17 months of legal employment in this country.

The mechanism for the granting of extra employment time in the country, and the reduction in tax payments, came through one of those multitudinous loopholes in the immigration law.

ICE has the task of defining the permitted economic activity of F-1 students; it has had, for years, an Optional Practical Training provision, which allowed such students to work in the United States with their F-1 visa for a year of training after graduation. ICE then decided to extend that period for 17 additional months for people with a long list28 of academic specialties.

It’s a bonanza for the foreign graduates and for their employers, and a disaster for competing legal resident college graduates.

Quasi-Amnesty Population Sizes

We will make no effort to estimate the combined population of quasi-amnesty beneficiaries, as there are too many overlapping groups, as well as a general lack of hard numbers. It is presumably a substantial fraction, but certainly much less than half, and probably much less than a quarter of the 21.3 million noncitizens that the Census Bureau estimated were living in the United States in 2009.29

Four other benchmarks also create a bit of perspective for the Quasi-Amnesty population estimates that follow. These are recent estimates of the following:

| Naturalized Citizens | 14.5 million30 |

| Permanent Resident Aliens | 12.5 million31 |

| Illegal Aliens | 10.8 million32 |

| IRCA Legalization of the 1980s | 2.7 million33 |

No population estimates are offered below for PRUCOL on the grounds that the program, as originally designed, is no longer in existence, and the remnants of that population, for federal purposes, are counted among Qualified Aliens.

Estimates on the three remaining classes of quasi-amnesty populations are based on the best data available, but in most cases they are no more than orders of magnitude guestimates, and should be regarded accordingly.

TPS

This is probably the smallest of the three active quasi-amnesty programs (the others being EADs and Qualified Aliens.) It is also the best defined and the only one with government-provided estimates of the size of the population.

Every 18 months or so, DHS issues another Federal Register notice extending the duration of each of the country-specific TPS designations, and when it does so it includes an estimate of the number of persons who are, at the time, in that status and can re-apply for an extension of the status. See, for instance, the 2010 extension for people from El Salvador.34 When these data are totaled for the most recent extensions we have these numbers:

| Nation | Latest DHS Estimate |

| El Salvador | 217,000 |

| Honduras | 66,000 |

| Haiti | 47,000 |

| Nicaragua | 3,000 |

| Sudan | 700 |

| Somalia | 300 |

| Total | 334,000 |

In addition, DHS estimates that 10,000 more Haitians will sign up during the current registration period; it is the only population where new registrations are being accepted, only re-registrations are taken from the others. Further, there are 3,600 Liberians in the TPS-like DED status mentioned earlier.

There are continuing slight declines in the sizes of the non-Haitian populations because, as time passes, and because no new arrivals are permitted, people drop out by dying, leaving the country, failing to re-register, or moving into other legal migration categories. The children of TPS parents become native-born U.S. citizens, and are thus not counted in these calculations.

There should be no overlaps between the TPS and the Qualified Alien populations, but there are substantial overlaps with the EAD grouping.

EAD

There is workload data from DHS on this population, but no government estimates of population size. The available numbers, however, can be used to provide a rough estimate of the size of the population.

As noted earlier, the EAD is a fee-producing document issued by USCIS. The principal statistical problem is that while we know how many applications were filed, and how many were approved, we do not know the average length of the approved EADs. An EAD (Form I-765) is issued, understandably, for the same length of time as the alien has been given legal status; this varies from a few months in some cases, to 18 months for TPS recipients, and longer for others. In order to get a rough order of magnitude of this population we have assumed that now, and in recent years, the average duration of an EAD is a year.

Unless I am misreading the situation, the EAD population, while much larger than the TPS population, has declined over the last 10 years. The number of applications filed in FY 2000 was about 1,813,000 and had declined to about 1,281,000 for FY 2010. This was a decline of 29 percent.

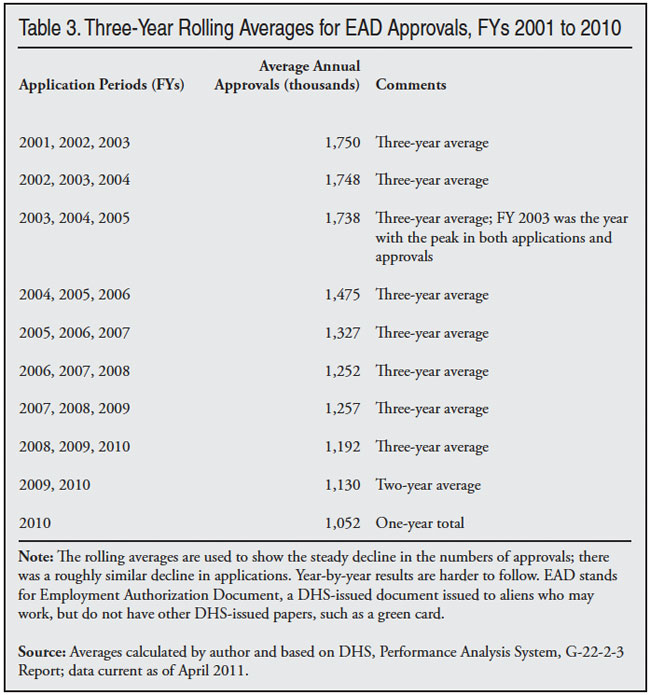

Apparently reflecting a slightly higher rate of denials in later years, as well as the underlying drop in applications, the percentage decline among the approvals was 38 percent, from about 1,698,000 in FY 2000 to about 1,052,000 in FY 2010, a trend that can be seen in Table 3.

I have no ready explanation as to why these trends took place.

So this population, presumably in excess of 1.0 million, is considerably larger than the TPS population, which it overlaps. It also overlaps, to some extent, the Qualified Alien population.

Qualified Aliens

This part of the quasi-amnesty population does not go through the kind of DHS-operated registration process that applies to the TPS and EAD aliens, and data on it, as a result, are considerably less precise. Qualified aliens are a subset of the noncitizens counted by SSA in connection with the payment of SSI benefits, the other alien recipients of these benefits being green card carriers. So we must turn to the SSI rolls for clues as to the number of Qualified Aliens. These estimates apply only to the non-PRA aliens among the Qualified Aliens, as some PRAs are included in the government’s definition of this group.

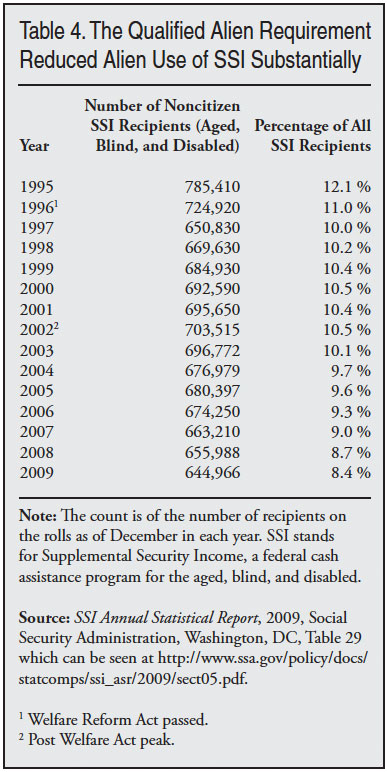

It is apparent from the SSI benefit rolls, as reported by SSA, that the replacement of PRUCOL by the Qualified Alien requirement has sharply cut the number of aliens receiving SSI benefits. For a summary of this trend, since 1995, see Table 4.

While there were 785,410 noncitizen SSI recipients in the nation in December 1995, 14 years later, in December 2009, there were only 644,966 of them. This is a reduction of 17.8 percent.

Meanwhile, according to the Census Bureau, the total estimated number of foreign-born noncitizens in the country over the age of 65 had increased from 1,112,000 to 1,261,000, or by 15.4 percent. So while the total population of older noncitizens was rising, the population of aliens receiving SSI benefits was falling, both in absolute numbers and in percentages. In 1995, 12.1 percent of SSI beneficiaries were noncitizens, by 2009 that had fallen to 8.4 percent.35

Clearly, the introduction of the Qualified Alien requirement made a major difference in the SSI use by aliens. I can think of no alternative theory to account for this decline in the use of SSI benefits. No one is arguing that the noncitizen elderly population, never anything but a low-income group, had suddenly secured unexpected wealth.36

As to the total number of Qualified Aliens who are not PRAs, there is a familiar problem. The government either knows or could know how many of them are PRAs, and how many are not, with the latter group being the non-PRA-Qualified Aliens, but it releases no data on that variable.

But there are five facts that we do know, and we can use them to make a rough guess of the size of the non-PRA Qualified Alien population.

We know from previously discussed statistics that there are about 15 percent more people in the PRA population than in the estimated illegal alien population, our crude proxy here for the non-PRA Qualified Alien population.

Secondly, we know that virtually all PRAs (who meet the income/poverty tests and the time limitations) are eligible for SSI and SNAP, but there are much smaller numbers of non-PRA Qualified Aliens who can meet the new, tougher requirements. Let’s estimate that there are 80 percent fewer of those eligible among the non-PRAs because of this variable.

Third, we know that at least half of the SSI noncitizen beneficiaries are over the age of 65, and that the incidence of the elderly among the illegal alien population is much lower than among other aliens.37 Let’s say that there is a 75 percent fall-off because of this variable, for the SSI estimates, but not the SNAP ones (because people of all ages get food stamps).

Fourth, Table 4 shows that there were about 645,000 noncitizens collecting SSI in 2009, including both PRAs and non-PRAs.

Finally, we can see from SNAP data38 that there are about 1,864,000 Qualified Aliens, including both PRAs and non-PRAs, who are on the SNAP rolls, but not39 the SSI rolls. My assumption is that virtually everyone collecting SSI or TANF benefits, or on the Medicaid rolls, is also on the SNAP rolls, that being the largest of the welfare programs, and the one with the least rigid economic requirements.

To estimate the percentage of the Qualified Alien population that does not have green cards on the SSI rolls, I then took the 645,000 and reduced it first by 15 percent, then by 80 percent, and then by 75 percent, taking into account the factors mentioned above (gross population size, tighter restrictions, smaller percentage of aged persons) to get a modest 4.25 percent of the original number, or about 27,000 non-PRA Qualified Alien recipients of SSI benefits.

Then, using the steps noted above, except for the final one, I estimate that the 1,864,000 noncitizens on the SNAP rolls consist of 17.5 percent non-PRAs, or 326,000, and 82.5 percent PRAs or 1,538,000.

So the total non-PRA Qualified Alien population receiving federally funded assistance is something on the order of 350,000, including the 326,000 SNAP recipients and, say, 24,000 aliens getting SSI, Medicaid, and/or TANF benefits without the receipt of food stamps.

Were PRUCOL still with us, there would be a substantial overlap between that population and the non-PRA Qualified Alien population. There should be no overlap between the latter group and those in TPS status. There are probably some overlaps between the populations of Qualified Aliens and EAD holders.

In summary, we have found something like these numbers for the three populations:40

| TPS | 334,000 |

| EADs | 1,000,000 |

| Qualified Aliens | 350,000 |

The first number is reasonably solid, the next one less so, and the third one the least reliable. All are considerably smaller than the estimate that there are 10.8 million illegal aliens in the nation, suggesting that the big majority of all non-green card-carrying aliens are not involved in any of these systems — or at least not yet.

It would be helpful if some congressional committee pried the actual numbers out of the government, but until that happens these crude, order-of-magnitude estimates are the only ones available.

Recommendations

The quasi-amnesties, as defined, are numerous, complex, significant, and generally overlooked, yet they play quietly powerful roles in the nation’s immigration policies. As a group they deserve more attention from Congress and from scholars.

These creeping, partial amnesties indirectly encourage additional migration, including illegal migration. They grant benefits to some aliens who should be benefit-free, such as those facing deportation.

The precedent of the existence of these quasi-amnesties and their almost hidden role in the broader picture provides too much of an opportunity for further, furtive mischief, particularly for an administration that seems to delight in this sort of thing. The whole business makes me feel profoundly uncomfortable.

Based on these findings I would make these recommendations:

- No More Quasi-Amnesties. Additional amnesties, or tweaks to existing ones, should generally be resisted. Given the administration’s frustration with Congress on “comprehensive immigration reform,” and given the seven mini-quasi-amnesties created in the last two years, more administrative softening of immigration policy is all too likely between now and Election Day 2012.

- Be Careful with TPS Expansions. Since the “temporary” in “temporary protected status” really means “permanent,” Congress should step in and redefine this program, and place strict limits on its exercise in the future. It might be confined to, say, a one-time, six-month or 12-month postponement of deportations to a nation in distress, and nothing more.

- Watch the Fees. A lesser point is that too often the softening of the immigration law leads to the non-collection of fees that are needed to support the entire system. Neither PRUCOL nor Qualified Alien status seems to generate fees for the government, but they both create serious workload burdens for tax-supported government workers.

- Watch the Numbers. There is a deplorable lack of comprehensive and detailed operating statistics on these programs, which should be corrected immediately. Often it is not that the statistics are not available, but rather that they are not published. In other instances, the numbers are not collected at all. Further, Congress should encourage the Government Accountability Office to mount studies in this field, particularly on the extent to which benefits are granted to those already found to be deportable.

- Watch Out for the Unknown Unknowns. To paraphrase the former Secretary of Defense, we must be alert for creative ways, not currently imagined, that the administration may devise to further weaken our immigration systems.

- Deny Benefits to Some Now Getting Them. While PRUCOL has been virtually eliminated from the federal lexicon, and the Qualified Alien definitions seem to be tight enough, someone other than the Department of Homeland Security should review the qualifications for EADs. Certainly those ruled deportable should be off the list, as should the dependents of L-1 nonimmigrants.

End Notes

1 The government does not use the term “quasi-amnesties;” I know of no existing collective term for these programs, which are rarely, if ever, discussed together.

2 Julia Preston, “U.S. Pledges to Raise Deportation Threshold,” The New York Times, June 18, 2011, p. A14, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/18/us/18immig.html.

3 For more on this, see the DHHS Fact Sheet issued at the time, at http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/abbrev/prwora96.htm.

4 The interesting and related question of aliens’ eligibility to receive Social Security benefits is beyond the scope of this report, but will be described in a separate CIS document in the near future.

5 See Holley v. Lavine, 605 F 2nd 638, Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit 1979 which can be seen at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8787980819278357573 . Gayle Holley was an illegal alien with six citizen children, and she sued Abe Lavine, then Commissioner of the New York State Department of Social Services, to recover the one-seventh of the AFDC grant that New York had denied her. After several years in the courts, Holley won, retroactively. INS had earlier decided that they while she was deportable, that action should be waived because of all the children.

6 See the Social Security Administration’s Programs Operations Manual System at Section SI 00501.420, at https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0500501420.

7 See http://www.cis.org/Immigration-Courts.

8 One tally of such states, prepared in 2002, showed that 10 states in addition to California and New York had made provision for extending at least some benefits to some or all

PRUCOL aliens in their states. Those states, at that time, were: Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Virginia, and Washington. See K. Chin, S. Dean and K. Patchan, “How Have States Responded to the Eligibility Restrictions of Legal Immigrants in Medicaid and SCHIP?” The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Washington, D.C., 2002, http://www.kff.org/medicaid/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile..... Note the use of “Legal Immigrants” in the report’s title. SCHIP, usually pronounced S-CHIP, is a federally supported health care program for low-income children.

9 See Note 6.

10 I suspect that they really meant “other nonimmigrant aliens” as many nonimmigrants could be included in some of

PRUCOL’s 18 listed categories.

11 Someone who is both a TPS status holder, and an F-1 foreign student, for example, could drop out of college and still remain in the nation legally, under TPS. Or that person could take fewer classes than the F-1 visa requires, and stay in college and in legal status because of TPS. That student, with an EAD in hand, could remain in college but work longer hours than would be permitted under the F-1 rules, and so on.

12 Before the creation of DHS these decisions were made by the Attorney General.

13 “Temporary Protected Status,” USCIS fact sheet updated on May 19, 2011,

http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.eb1d4c2a3e5b9ac89243c6a7....

14 For the USCIS announcement of the TPS/DED conversion on September 12, 2007, see http://www.dhs.gov/xnews/releases/pr_1189693482537.shtm.

15 From the DHS Office of Immigration Statistics, Performance Analysis System, G-22-2-3 Report. Data current as of April 2011.

16 See http://www.uscis.gov/files/form/i-765instr.pdf.

17 See my blog on the subject at http://www.cis.org/north/widening-loopholes. For the full text of the Federal Register notice of August 9, 2010, see http://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2010/08/09/201019620/employment-....

18 See my blog at http://www.cis.org/north/same-sex-partners-for-diplomats. To the best of my knowledge there was no Federal Register notice of this change, only the New York Daily News article cited in the blog.

19 These nations are the Republics of Palau and of the Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia; their citizens can live and work in the United States permanently in a congressionally created nonimmigrant status, but they need EADs to do so. There has been a substantial movement (by island population standards) from these mid-Pacific island nations to Guam, CNMI, and Hawaii, but not much to the mainland.

20 See DHS, Performance Analysis System, G-22-2-3 Report. Data current as of April 2011.

21 See her “Immigrants’ Access to Public Benefits: Who Remains Eligible for What,” a 1999 document at http://sogpubs.unc.edu/electronicversions/pg/immi.htm.

22 See the relevant section of the Social Security Handbook at http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/handbook/handbook.21/handbook-2115.html. In addition to the Qualified Aliens, discussed above, there are four small categories of aliens who are not regarded as “qualified” but may get SSI anyway. These are non-citizen Indians belonging to a federally recognized tribes, American Indians born in Canada, aliens who are victims of severe forms of trafficking, and some Iraqis or Afghans who served as interpreters for the U.S. military.

23 See, for example, this USCIS announcement of the fee waivers http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.5af9bb95919f35e66f614176....

24 See the Federal Register for May 19, 2011, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-05-19/html/2011-12440.htm.

25 For a concerned immigration lawyer’s take on all this, see http://www.law.com/jsp/law/LawArticleFriendly.jsp?id=1202446090058 and for my own observations, see this blog and the references therein: http://www.cis.org/north/haiti-tps-extended. There is a further element, regarding the size of the illegal alien population from Haiti, and that is the relative difficulty for entrance without inspection for low-income Haitians, as opposed to low-income Mexicans; the latter can, simply by walking a lot, enter the United States as an EWI, while the former must pay to take a long sea voyage on what are usually old and over-crowded, or “rustic” vessels, to use the Coast Guard’s term.

26 The ICE announcement on the Libyan students can be seen at http://www.ice.gov/news/library/factsheets/libyan-student-employment.htm.

27 This ICE announcement can be seen at http://www.ice.gov/news/releases/1105/110512washingtondc2.htm; for my own comments, see http://www.cis.org/north/expanded-OPT-stem-list.

28 The list of occupations can be seen at http://www.ice.gov/doclib/sevis/pdf/stem-list-2011.pdf.

29 See U.S. Census, Foreign-Born Population of the United States Current Population Survey - March 2009, Characteristics of the Foreign-Born Population by Nativity and U.S. Citizenship Status, Table 1.1.

30 Ibid.

31 Nancy Rytina, “Estimates of the Legal Permanent Resident Population in 2009”, Office of Immigration Statistics, DHS, Washington, 2010, http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/lpr_pe_2009.pdf.

32 Michael Hoefer, Nancy Rytina, and Bryan C. Baker, “Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2009,” Office of Immigration Statistics, DHS, Washington, 2010, http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/ois_ill_pe_20.... Note that the two DHS estimates of unauthorized and permanent resident aliens total at 23.3 million, while the Census estimate of noncitizens is two million less, reflecting the differing methodologies and definitions used by the two agencies.

33 Nancy Rytina, “IRCA Legalization Effects: Lawful Permanent Residence and Naturalization through 2001” Statistics Division, U.S. INS, Washington, 2002, Exhibit 1.

34 See the Federal Register of July 9, 2010, http://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2010/07/09/201016431/extension-o....

35 There are two classes of SSI applicants: the aged, and the blind and/or disabled. The decline in the usage of SSI among noncitizens is caused, almost exclusively, by the decline in older recipients, not the disabled ones. In 1995 there were 459,220 aged noncitizen recipients with that number falling to 316,216 in 2009; meanwhile the number of disabled noncitizens remained almost stable, with there being 326,190 of them in 1995 and 328,750 in 2009. When a blind or disabled SSI recipient reaches 65 that person is switched to the aged category. These numbers are from the same source as Table 4.

36 There is a somewhat similar situation with the SNAP program. Although noncitizens are well known to have lower incomes than citizens, the percentage of noncitizens on the SNAP rolls in 2009 was 7.0 percent, which was just what their percentage was in the total population that year. The tougher requirements of the Qualified Alien category must have played a role in the lower-than-to-be-expected participation of aliens in SNAP. For the percentage of noncitizens in the United States see Note 29; for the SNAP utilization data, see Note 38.

37 The DHS estimates of the Unauthorized Alien population (cited in Note 32) say that only 3.5 percent of that population is 55 or over, while according to Census Bureau data, 13.4 percent of the noncitizen population were 55 or older.

38 These estimates are drawn from Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2009, Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, October 2010, Table A-1, http://www.fns.usda.gov/ora/menu/Published/snap/FILES/Participation/2009....

39 The multiple negative categories used in this text are reflections of the terminology in the Department of Agriculture table cited in the previous endnote which, at one point, has the following entry:

“Noncitizens 7.0 percent

“No Noncitizens 93.0 percent”

While others might think that the opposite of noncitizens is citizens, the SNAP program does not.

40 Not included in these estimates are the three relatively small populations noted at the bottom of Table 2: same-sex partners of U.S. diplomats, the OPT/F-1 recent graduates with certain academic specialties, and the F-1 students from Libya.