[NOTE: In some versions of the press release, there is a reference to 125 miles of New Mexico border. That is incorrect; the release should refer to 25 miles.]

The border area between New Mexico and Mexico is sparsely populated and has limited natural or man made barriers to illegal crossing. This, coupled with an extensive road network that traverses the state in all directions, makes New Mexico a haven for the transshipment of illegal drugs from Mexico to destination points throughout the United States.

Current enhanced enforcement operations by the Department of Homeland Security in Arizona will most likely force drug traffickers and alien smugglers to shift their smuggling efforts from Arizona to New Mexico. This, in turn, will have a serious impact on enforcement operations and judicial proceedings in New Mexico. While additional enhancements for Border Patrol agents in southern New Mexico has somewhat mitigated the increased use of southern New Mexico as a viable route for alien smuggling, there has been a marked increase in the number of drug seizures and apprehensions of illegal aliens.

- DEA New Mexico Report (2008)

Obviously, the impact of the [Wilderness] policy is severe on our operations. When you can't drive in those areas, it makes it impossible to patrol and enforce the law, and it transforms it into a sanctuary for illegal aliens."

- T.J. Bonner, President, National Border Patrol Council, the union representing more than 12,000 Border Patrol agents (July 2010)

To date, discussion of the porous Southwest border has largely left out New Mexico. That is about to change if Senators Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.), Chairman of the Senate Committee on Energy & Natural Resources, and Tom Udall (D-N.M.) are able to pass an otherwise innocuous bill that changes which laws apply to a stretch of federal land on the New Mexico border. The bottom line is, if S. 1689, the "Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks Wilderness Act," becomes law, New Mexico will likely become the next staging ground for drug cartel and illegal alien smuggling activity, tracking what happened in Arizona. Why? The bill would change the designation of Department of Interior lands, managed by the Bureau of Land Management, from "public lands" to "wilderness," severely curtailing the Border Patrol's ability to conduct preventative, ongoing, and necessary operations due to the stringent nature of wilderness laws that are now four decades old. New Mexico would suffer the same results as those documented by the Center in the "Hidden Cameras on the Arizona Border" three-part series showing the waste, destruction, and unsafe circumstances that borderlands suffer when wilderness laws (and poor federal government policy) create a vacuum of law enforcement presence.

The Bill

S. 1689 was passed out of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee on July 21, 2010, by voice vote and is now awaiting consideration on the Senate floor. Specifically, S. 1689 "designates as wilderness 241,400 acres of public land managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in Dona Ana County in southern New Mexico." According to the bill's September 20, 2010, Senate Committee Report its purpose is as follows:

The wilderness and conservation areas would provide protection for large expanses of the Chihuahuan Desert ecosystem, including mountain ranges and grasslands, mesas and canyons, and lava flows and extinct volcanic cinder cones… The region provides important wildlife habitat for both game and sensitive species, and contains a number of archeological and historical sites, including petroglyphs, throughout the area. The proposed-Desert Peaks National Conservation Area lies adjacent to the Prehistoric Trackways National Monument and may contain similar archeological resources as the National Monument.

The bill makes clear at the outset that the Border Patrol's mission is respected and reiterates that access is granted for "undertaking law enforcement and border security activities" under the terms of the wilderness law and a 2006 agreement between the Departments of Homeland Security, Interior, and Agriculture; it also permits low-level overflights of the designated areas. While these elements are superficially supportive of the Border Patrol's already difficult mission in this area (part of the Border Patrol's El Paso Sector), in reality a wilderness designation for borderlands has proven to be severely detrimental to the land itself. The reason: While our government is constrained by law from patrol operations, the illegal smugglers and drug cartels operate outside the law, abusing and destroying the land for illegal purposes, threatening public safety and potentially national security. In addition, the El Paso Border Patrol Sector, which includes the lands allocated by S. 1689 to wilderness, is already deemed 27 percent uncontrolled according the sector chief. A wilderness designation would further exacerbate an existing problem.

Wilderness Laws

In environmental law, federal land designations have wide influence over who and what has access to these lands. In the context of borderlands, a public use designation allows the Border Patrol relatively unfettered access for law enforcement actions, if they choose to use it. Such public lands were the focus of the push to clean up Yuma, Arizona, in Operation Jumpstart from 2006 to 2008, for example, including the deployment of 5,489 National Guard troops to the area and the building of over 100 miles of effective fencing. The result was that over a two-year period, Yuma went from the Border Patrol being outnumbered by 50-to-1 on a daily basis and assaulted daily by smugglers of all kinds to a 94 percent drop in apprehensions and a manageable sector today.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, a wilderness designation on borderlands such as those in the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge and Organ Pipe National Monument, both in western Arizona, changes the operational landscape so significantly that few operations can occur unless in "hot pursuit" of known, real-time illegal activity. Nearly the entire expanse of both of these wilderness parks has been negatively impacted by illegal activity, as demonstrated by Department of Interior PowerPoints obtained through 2009 Freedom of Information Act requests. We highlighted the Organ Pipe PowerPoint in our "Hidden Cameras on the Arizona Border 2" video released in July 2010, showing that nearly all of the Monument had been damaged by illegal activity.

To operate in wilderness areas requires tedious bureaucratic requests to the Department of Interior. Operating bases are not permitted. In addition, once land is labeled "wilderness," the Border Patrol must pay mitigation fees for repairing land "harmed" while in the pursuit of illegal activity. Despite the fees, this does not permit greater use of the lands. Instead, every specific task or operational strategy the Border Patrol considers requires approval processes that, in general, prevent timely and effective operations. As a result of the legal barriers that a wilderness designation brings, the Border Patrol loses both incentive and the ability to work on such lands. For example, low-level flights are of minimal value if Border Patrol agents can only act on what they see if they can assure their Interior Department colleagues afterwards that the activity they acted on was a crime or rescue. In addition, the Border Patrol has to be willing to incur mitigation fees. The cartels know this, and they are already chomping at the bit for another American welcome mat.

Drug Cartels in S. 1689 Territory

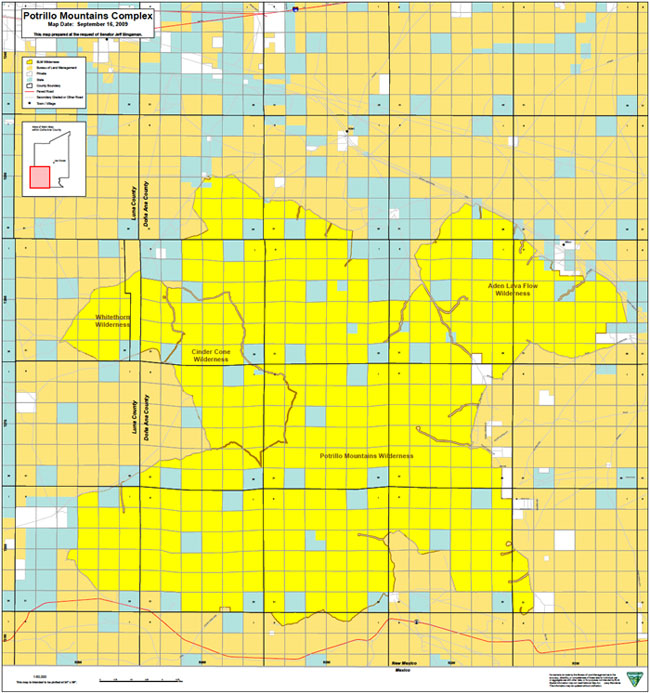

Drug cartel forays have already begun in the area Sen. Bingaman wants to designate as wilderness. The parcel spans the middle of New Mexico, where Texas meets the New Mexico border, running about 25 miles from east to west within a mile of the U.S.-Mexico border and about 25 miles north of the border. The land is specified as the Potrillo Mountains Complex, a series of mountains that include oil and gas pipelines (but were excluded from the bill). The specific areas covered by the bill expand beyond the Potrillos (West and East Potrillo Mountains, Aden Lava Flow, and Mt. Riley) to other pockets spanning north. These are: the Sierra de Las Uvas, Robledo and Organ Mountains as well as Broad Canyon and represent potential extensions of corridors north of the Potrillo Mountain Complex, and another series of safe haven pockets. (Essentially enabling these designations further north to become roughly analogous to the public lands now overrun by cartels and smugglers between Tucson and Phoenix in Arizona.) The area encompassed in S. 1689 was highlighted in an October 2, 2010, Associated Press report, reporting that law enforcement is picking up on “obvious” drug cartel forays in Dona Ana County’s Department of Interior lands:

LAS CRUCES, N.M. -- Southern New Mexico law enforcement agencies say drug investigations in Dona Ana County are related to two Mexican drug cartels.

Authorities have confiscated more than $400,000 in four separate seizures as they investigate Mexican drug- and weapons-trafficking organizations.

Metro Narcotics Sgt. Bobby Holden says a narcotics agent and a sheriff's deputy with guns drawn stopped a Mexico-bound car on N.M. 273 in Sunland Park last week.

Holden says they found four men with two handguns and $40,000 in cash hidden in a floor compartment.

He says the men are being detained. Their names and citizenship have not been released.

Holden says cartels are conducting "obvious" forays into the local drug trade.

He says every bit of cocaine or marijuana that's sold comes from them, directly or indirectly.

Wilderness Designations' Contribution to Arizona Borderland Destruction

While an environmental "need" for the designation may be justifiable in theory to protect ecosystems, the reality is that the new designation will open this Dona Ana County land to destruction. S. 1689 would likely create a 25-mile borderland pathway for illegal activity that would replicate the environmental destruction and public safety issues that have sent Arizona into confrontation with the federal government on immigration enforcement, raising real concerns about our national security. Due to an increase of infrastructure on the terrain previously heavily trafficked by smugglers, smuggling activity is squeezing increasingly in the more desolate and difficult wilderness lands like the area covered by S. 1689.

Border Patrol numbers clarify that there has been a significant increase in abuse of these lands since the fencing and operational surges began in 2006; from 2007 to the middle of 2009, the Border Patrol apprehended a total of 5,639 illegals on wilderness lands. However, just for the 90 days of summer in 2009 – when traditionally the heat minimizes illegal activity – there were 3,523 arrests, an increase of over 400 percent in arrests on wilderness lands. Even this number is likely a fraction of illegal activity, considering that we are sure many pass through undocumented, as shown in our first and second "Hidden Cameras on the Arizona Border" mini-documentaries. One particular point of concern from the first film is the Border Patrol map showing thousands of illegal trails on Arizona federal land, making a potential of hundreds of thousands of successful entries based on the numbers we extrapolated in those films. None of these statistics exist in federal reports, however, of course. Obviously, no institution counts the illegal activity not caught.

This surge in abuse of federal lands, and particularly wilderness lands, is predictable. Many of Arizona’s current problems could have been averted with a combination of a solid operational strategy for the Border Patrol that included an open discussion and resolution of the problems posed by well-intentioned wilderness laws not designed – nor amended – to deal with the current situation on U.S. borders. Instead, a 2006 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Departments of Interior and Agriculture, initiated by the Department of Homeland Security in an attempt to address these problems, actually appears to further constrain the Border Patrol from successful operations. The MOU includes 21 requirements, or hoops that the Border Patrol must jump through, to build infrastructure on protected lands, let alone enter or conduct operations. Exceptions exist only if agents are on foot or horseback, on a public road, or in hot pursuit. However, these exceptions were already spelled out in the wilderness laws. What was added into the MOU was funding for the Department of Interior via "mitigation fee" requirements mentioned above.

Protecting the environment is obviously a good thing. But if the Border Patrol cannot do its job and the cartels know it, pristine borderlands will be overrun with trash and made unsafe. To be sure, that result seems counter intuitive and counter to S. 1689's language. The legislation does provide a five-mile stretch of access to the Border Patrol on the border, and it is positive that the Department of Interior supports this access, as was stated by Marcilynn Burke, Deputy Director of the Bureau of Land Management, in her testimony before the Energy and Natural Resources Committee in October 2009 on S. 1689: "The legislation releases a substantial swath of land along the border with Mexico that is currently designated as WSA [Wilderness Study Area] from WSA restrictions. The release contemplated by the legislation would allow greater flexibility for law enforcement along the border. We support this WSA release."

S. 1689 also reiterates that the Border Patrol can use the wilderness in "exigent" circumstances and relies on the 2006 MOU as sufficient support for law enforcement activity in these Potrillo Mountains. The Committee Report reiterates this point as follows:

Section 7(a) clarifies that nothing in the Act: Prevents the Department of Homeland Security from undertaking law enforcement and border security activities within the wilderness areas while in pursuit of a suspect, in accordance with section 4(c) of the Wilderness Act (16 U.S.C. 1133(c)), including the use of motorized vehicles; affects the 2006 Memorandum of Understanding among the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of the Interior, and the Department of Agriculture regarding cooperative national security and counter-terrorism efforts on Federal land along the borders of the United States; or prevents the Secretary of Homeland Security from conducting any low-level overflights over the wilderness areas designated by this Act.

However, while an improvement over no access, the legislation at the same time shuts down most of the remaining 20 miles north of border covered by the wilderness designation. Again, this is because the wilderness designation means, according to the GAO, that the Border Patrol is severely restricted in gaining access to the land. As the GAO described in an unpublished early draft of its June 2004 report "Border Security: Agencies Need to Better Coordinate Their Strategies and Operations on Federal Lands" (obtained by the Center through a 2009 Freedom of Information Act request to the Fish and Wildlife Service), a wilderness designation significantly curtails Border Patrol and other law enforcement operations:

Since the mid-1960s, Congress has passed legislation (P.L. 88-577) to designate certain areas within federal lands, called wilderness areas, to protect special features and characteristics of the land. In designated wilderness areas, all motorized access and infrastructure development is generally prohibited, including activities by federal employees and law enforcement officers, except in emergency situations involving the health and safety of people. Many of the federal lands along the Mexican and Canadian borders have portions of land designated as wilderness areas, and they pose particular challenges for land management law enforcement officers and Border Patrol agents in patrolling these lands. The wilderness laws require law enforcement officers and agents to keep all motorized vehicles on specified administrative roads, and prohibit off road driving unless in pursuit of a person suspected of a crime, or in conduct of a search and rescue operation. Further, wilderness laws generally prohibit the permanent installation of buildings, technology and infrastructure – such as towers used to relay communication signals or towers used to attach remotely operated surveillance cameras – typically used by law enforcement to monitor illegal activities occurring along the borders. Federal agencies have obtained exceptions to the wilderness laws through environmental clearance processes; however, complying with these proceedings can be lengthy and costly. (p.6)

It is already hard enough for the Border Patrol to set up a forwarding operating base on "public lands." A good example of this difficulty is on land about 125 miles east of the Arizona state line in the area that would be affected by S. 1689. A rancher 11 miles north of the border granted permission to the Border Patrol to lease a parcel of her property for a forward operating base in Hildago County, New Mexico, in the spring of 2010, following the murder of southeast Arizona rancher Rob Krentz. Yet squabbling among the property owners, the Border Patrol, and the Bureau of Land Management has resulted in the new base still not built 20 miles inside the border, angering those residents who want protection closer to the border and those concerned about a Border Patrol base's environmental impact. These political challenges are difficult enough without the wilderness laws adding another layer of difficulty that has amounted to years of delay for similar requests pertaining to radio and surveillance towers and bases, sometimes amounting to years before they are resolved.

Effect of the 2006 MOU

As mentioned, the 2006 MOU between the Departments of Homeland Security, Interior, and Agriculture (Forest Service) attempts to address these issues. However, a close review of the document indicates that the Border Patrol was simply given all the limited access that the laws had already provided alongside the mitigation fee requirement. To date, the Border Patrol has paid at least $75 million for preserving and repairing abused wildlife areas, about $67 million of which has gone directly into the Department of Interior’s coffers. The current status of the Border Patrol’s access to wilderness lands was described by the Border Patrol to Congress in a formal document request response dated October 2, 2009. The conclusion: The U.S. Border Patrol is no better off than it was before the MOU. In fact, more requirements now rest on it than before. Here is an excerpt of the agency's answers to Rep. Bishop:

Maintenance of our operational effectiveness on wilderness lands has always been important to the USBP. Federal land managers understand the duties of the USBP with regard to operations on lands under their care, yet there remains a much higher level of difficulty associated with operations within wilderness and on other special land types. The purpose of the 2006 Tri-Departmental MOU is to resolve these difficulties. One issue affecting the efficacy of Border Patrol operations within wilderness is the prohibition against mechanical conveyances (land and air.) The USBP regularly depends upon these conveyances, the removal of such advantage being generally detrimental to its ability to accomplish the national security mission. While the USBP recognizes the importance and value of wilderness area designations, they can have a significant impact on USBP operations in border regions. This includes that these types of restrictions can impact the efficacy of operations and be a hindrance to the maintenance of officer safety. The USBP, in accordance with the 2006 MOU, makes every reasonable effort to use the least impacting means of transportation within wilderness; however along the southwest border it can be detrimental to the most effective accomplishment of the mission. For example, it may be inadvisable for officer safety to wait for the arrival of horses for pursuit purposes, or to attempt to apprehend smuggling vehicles within wilderness with a less capable form of transportation. However, it should be noted that the MOU makes allowances for emergency access to these areas under certain circumstances and involves certain notification processes.

Mitigation Fees as Disincentive to Operate on Wilderness Lands

As to mitigation of environmental impact of its activity on federal land, the Border Patrol argues that the wilderness designation should no longer require it to pay mitigation fees. Instead, the positive effect of keeping illegal activity off the wilderness areas that destroys coveted open spaces should be more than sufficient to counteract a need to, essentially, pay the Department of Interior for operations on federal land that help free the wilderness areas from the illegal activity that destroys it. From the same response to Congress, the following:

Overall, the removal of cross-border violators from public lands is a value to the environment as well as to the mission of the land managers. The USBP believes that operations are generally functionally equivalent to mitigation. Recognition of this equivalency could prevent what we see as unnecessary and potentially very large mitigation requirements. The validity of this statement was evidenced recently when the vehicle fence project south of the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge received praise from a Fish and Wildlife Biologist. The biologist was encouraged by the re-growth and rehabilitation taking place naturally to the north of the vehicle fence subsequent to its installation. The Coronado National Forest Supervisor has been very supportive of our projects, likely due to his recognition of their ability to reduce illegal cross-border traffic and minimize the operational footprint of the USBP simultaneously.

Conclusion

While there is no doubt that the incentive for changing a public use designation to a wilderness designation is to support legitimate environmental conservation, on today's borderlands such a designation will assuredly result in that area’s destruction, as acknowledged by the Department of Interior itself in lengthy studies on the impact of illegal activity on refuges such as Organ Pipe National Monument and Buenos Aires National Refuge in Arizona.

S. 1689, the "Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks Wilderness Act" will provide the Border Patrol with little ability and little incentive to do its job under law, let alone state, local and other federal law enforcement. New Mexico will become another staging ground for drug cartel and illegal alien smuggling activity. Trash, waste, public safety and national security issues would likely overrun southern New Mexico’s Dona Ana County, replicating Arizona's problems. A better legal change would be to help to assure conservation by keeping the cartels under control and protecting our public safety and national security with adequate law enforcement and infrastructure.