Honduran migrants staging for a Texas border crossing earlier this week in Piedras Negras, Mexico, across from Eagle Pass, Texas.

PIEDRAS NEGRAS, Mexico — Last month in Juarez, I interviewed Central American migrants planning to return to their home countries rather than waiting in Mexico for U.S. asylum hearings. More than 25,000 of them had been ejected under President Donald Trump's "Remain in Mexico" policy.

In a July 22 blog, I cited these return plans as early anecdotal indication that the Remain in Mexico policy, formally known as the Migration Protection Protocols or MPP appeared to be succeeding in demagnetizing the ultimate prize of living illegally in the United States once migrants lose claims to asylum.

Deterring Central Americans from making meritless asylum claims simply as a means of entering the U.S. was a primary deterring goal of the MPP. The Los Angeles Times followed my reporting on August 4, as have other media outlets since.

But, as always, there's more to the story now. The MPP policy is having a very different impact on the thinking of other Central American migrants, as I found this week in this mid-sized Mexican city of 150,000, across the Rio Grande from the Texas town of Eagle Pass.

All three of these Hondurans said they would crash the U.S. border and evade the Border Patrol rather than turn themselves in and claim asylum.

Here, I found a dozen Hondurans congregating in the shade of a charity shelter that was too full to accommodate them, just six blocks from the Rio Grande — single men as well as two families with children. They gathered around to tell me that, rather than giving up and going home, they were all staging there for an illegal U.S. entry either that night or the following morning. What was especially noteworthy was that they planned to use a strategy radically different than the one used by hundreds of thousands who had crossed before the MPP policy was announced.

Whereas almost all Central Americans who illegally entered the United States prior to the new policy actively and immediately sought out U.S. Border Patrol agents so they could make their asylum claims and be quickly released legally, these migrants were planning to run, hide, and evade the Border Patrol at all costs to reach the American interior undetected.

They were frank in the reasoning: The MPP policy might land them right back in Mexico, where they'd be expected to wait for their asylum claims to slowly process through the backlogged U.S. system — and then find themselves perpetually stuck in Mexico once they lost their asylum claims, as almost all of them will. That wasn't an option for these economic migrants.

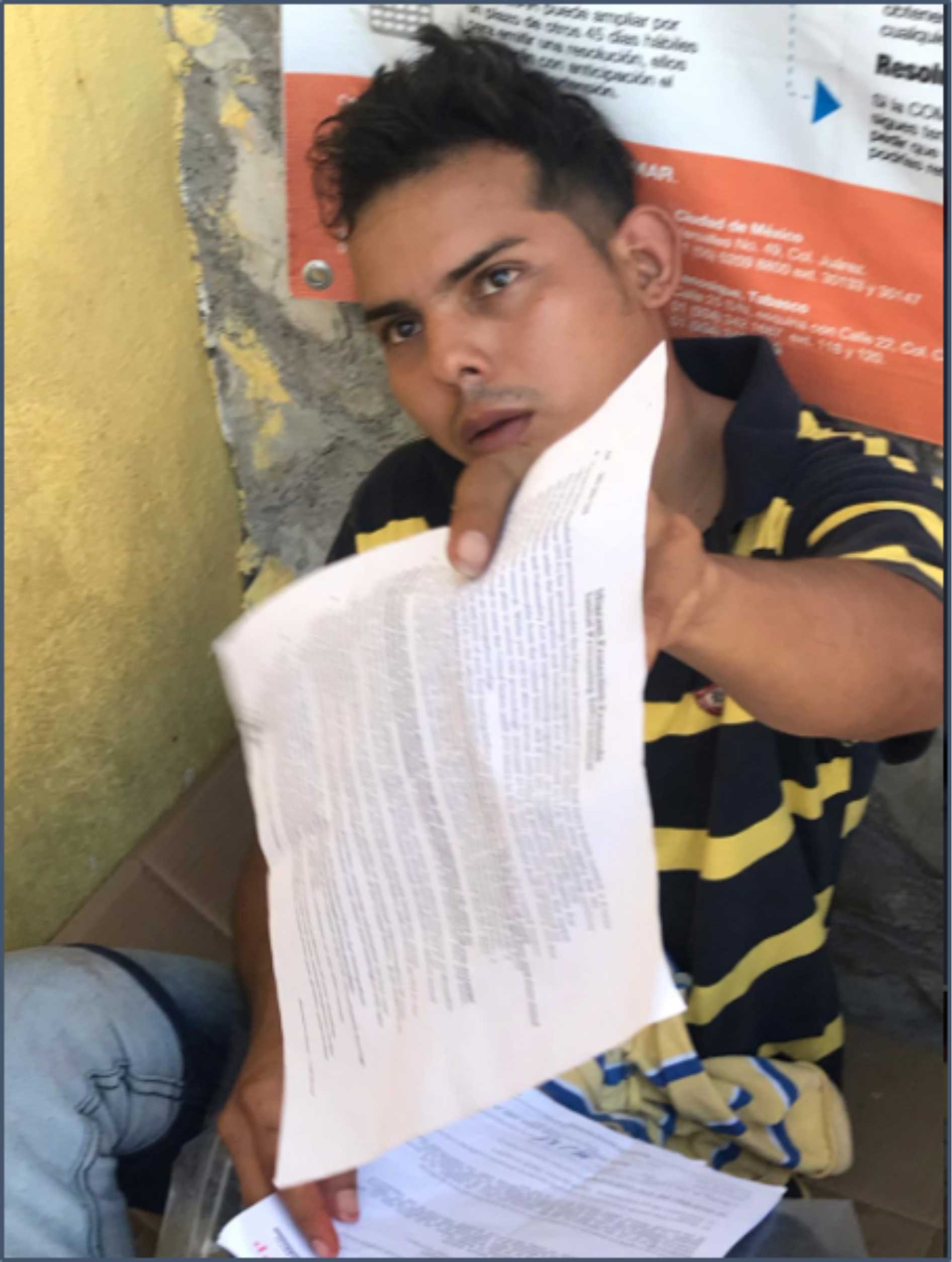

Pablo Adaman Perez-Lara of Honduras showing his MPP Notice to Appear recently in Piedras Negras, Mexico. All of the migrants around him were acutely aware of his experience.

"Our objective is to not get caught by Border Patrol because they'll turn us back," said Honduran Selvin Ulloa, 22, who said he had scouted the river earlier that day and found a good crossing point.

Everyone gathered around me knew this to be true, not least by the presence at the shelter of Pablo Adaman Perez-Lara, a 27-year-old Honduran returned to Piedras Negras under MPP. He showed me the documents to prove it. He said he planned to actually wait in Mexico but wasn't sure if he'd make a run for the border if the asylum thing doesn't go his way.

At least two others in the group said they had once lived in the United States, were deported (most likely after committing crimes), and had made their way back. They, too, felt their only option was to breach the U.S. border and live illegally once again. They'd go in with the rest of the group here.

This field reporting confirmed something else that Border Patrol agents had been telling me confidentially after my first report: that many migrants who are returned to Mexico under MPP are simply crumpling up their documents, turning right around, and running back through, hoping to evade the Border Patrol this time for that holy grail of illegal U.S. living. When they are caught (and agents are able to check a database confirming they had earlier made asylum claims and were thus subject to MPP), there are no legal repercussions at all; the economic migrants are simply returned to Mexico again, where at least some can be expected to keep trying their luck until they do get through to the American interior.

I recently asked three active-duty Border Patrol agents who work in different border sectors if this is really happening. Are MPP returnees turning right around and crashing the border?

"Yes. Especially in places like the (Rio Grande Valley sector) right now," one told me.

The odds of successful illegal entry favor these economic migrants right now, too, I was told.

"If there are groups of 100-plus at a time to one agent in the field for a few miles, well, let's just say we can only do so much," one Border Patrol agent told me.

The two families at the Piedras Negras facility said they, too, feared they would be returned under MPP and also would try evading the Border Patrol if possible, alongside the single men and women at the Piedras Negras shelter. Their success in doing so, however, seemed unlikely if for no other reason than that children are slow and have many needs that would have to be met on a long, hot, overland journey during summer.

To be sure, some family units have been returned under MPP. But two area Border Patrol agents told me they are still quick-releasing large numbers of Central American economic migrant family units who keep crossing, due to the 20-year-old Flores legal settlement that prevents their detention for longer than three weeks.

If these families are caught, as they likely will be, and still end up back in Mexico under MPP, they may find themselves tempted to return home aboard buses now being provided by the United Nations International Organization for Migration, as my colleague David North first pointed out last month. But the odds seem greater that, after apprehension on the U.S. side, they’ll just be released under Flores.

So, like many other aspects of border security management, the MPP policy may well be working to some extent, as I reported a few weeks ago in Juarez. But the nuances can be hard to catch at first blush. Most families are still being let into the country after the Border Patrol encounters them. Should MPP be expanded to include far more of them?

And while MPP clearly is deterring and motivating some migrants to give up the asylum gambit and go home, we now should say its impact is not the same on the thinking of all migrants. Others subjected to MPP will become what Border Patrol agents call "runners"; they'll seek an American dream of easy illegality quite in spite of their future American hosts and their distant policy-making in Washington, D.C.