I recently returned from a tour that took me cross-country through Texas to the Rio Grande Valley (RGV) and beyond. What I saw presented a slightly different view from that driving the debate on border walls and amnesties.

The border part of my trip began in Austin, more than 300 miles north of the RGV. Interstate highways led me past the city, 70 miles down the road to San Antonio toward Corpus Christi, before turning off onto U.S. 281, a desolate stretch of highway that will soon become part of Interstate 69 (I-69). This interstate will eventually run from Texas to seven other states: Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. The road work has already begun on vast stretches of the road, with significant improvements in some places, but years-old blacktop in others. Around McAllen, I was told that the route would likely carry citrus and other goods north into the eastern United States, but will not rival its sister interstate to the west, I-35, which helps to make Laredo America's busiest inland port.

Interestingly, tourism appears to be part of the I-69 scheme. Miles north of the first major city on the road, Edinburg, signs announce that you are in the "Texas Tropical Trail" region, and a few miles further down the road from the first signs, what appeared to be recently planted palm trees appeared in the median. Not much of the northern area of the region suggests the tropics, however, as oil and gas fields, cotton patches, and ranches (and road construction equipment) line the roadway. Improvements are few, and most of the gas stations on the side of the road are closed.

The approach into Edinburg and the RGV, however, provides a stark contrast to the immediately adjacent area to the north. A new 9,700-seat soccer stadium (H-E-B Park, home of the Rio Grande Valley Toros soccer team) appears just off in the distance, as do new malls and housing developments. The McAllen-Edinburg-Mission Metropolitan Statistical Area is now the fifth largest in the state, recently surpassing El Paso; with a population that already totaled 842,304 in July 2015, McAllen is growing twice as fast as El Paso itself. And, its population is young: at 28.4 years, the median age in McAllen is about nine years younger than the national average.

With this have come the many businesses that cater to young adults. Chain restaurants and bars line the highway (I-2), as do big-box stores. Sprinklers water the lawns of half-million-dollar houses. Two hospitals sit side-by-side facing I-2. The morning traffic is what you would expect to find in a first-tier suburb, and the area reminded me of Orange County, Calif., in the 1990s, or Arlington County, Va., in the last decade.

Vestiges of the border town still exist, however. There are trailer parks, and the muddy boots of the agricultural and construction workers who are passing through town or working on its outskirts lined the hallways of the motel where I stayed. The music at the Appleby's where I ate was all in Spanish, and on a Tuesday night, the televisions showed boxing and soccer exclusively.

So who are these residents? Some were locals, while others told me they had come to the area to work in the restaurants and businesses. Some work in the industries that support the port: shipping, storage, and warehouses. Plants employ workers who process parts that are shipped for assembly in maquiladoras in Mexico, or broken tools sent south to be refurbished.

There were suggestions, however, that other residents were there for different reasons. The cartel crime that has plagued the northern Mexican states has driven those with the status and the resources to cross the border to do so. And, it was implied, some of those cartel members had come to live in McAllen as well, safe from the danger that is a consequence of their chosen profession.

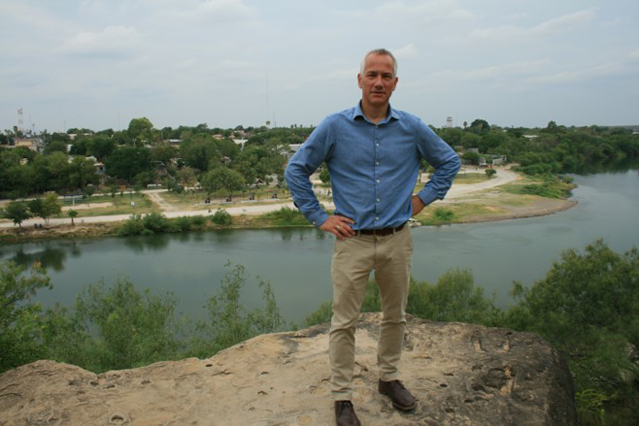

On the river, however, it is apparent that you are in a border town. Just down from the Anzalduas Dam are two parks that face each other across the river. Anzalduas Park on the U.S. side of the border sits a few hundred feet across the river from what Google Maps identifies as the Centro Cultural y Recreativo la Playita Reynosa, in an area Texas Monthly spotlighted in an October 2014 article on the surge of children and families from Central America.

When I was there, at about 11:00 AM, a handful of families were in the Mexican park, some of whom were splashing around in the green water of the river; others were holding picnics in the park. In contrast, Border Patrol boats and heavily armed Texas Highway Patrol vessels were leaving from the dock on the American side to search for drug and alien smugglers.

The boats pass large, expensive homes with pool houses on the Mexican side, as well as what would appear to be scout platforms on the southern side of the river.

While there are stands of vegetation on the Mexican side, it is nowhere near as thick (or ubiquitous) as on the American side, where carrizo cane (or Arundo) runs from the shore to yards up the riverbank for miles at a time.

As the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board (TSSWCB) has noted:

Large dense stands of non-native carrizo cane (Arundo donax) now occupy the banks and floodplains of the Rio Grande, thwarting law enforcement efforts along the international border, impeding and concealing the detection of criminal activity, restricting law enforcement officers' access to riverbanks, and impairing the ecological function and biodiversity of the Rio Grande.

Arundo is an exceptionally fast growing plant, able to grow about 4 inches per day and reach a mature height of over 25 feet in about 12 months. These stands of invasive riparian weeds present considerable obstacles for the protection of the international border by law enforcement and agricultural inspectors, by both significantly reducing visibility within enforcement areas and by providing favorable habitat for agriculturally-damaging cattle ticks.

Once inside the cane on the American side of the river, it would be difficult to spot illegal entrants. It would be harder still to pursue them from the river, given the difficulty of running up the sandy riverside.

In any event, once up the bank and into the cane, it would be easy for an entrant to access the town of Mission, and the United States, which has required a heavy Border Patrol presence in the area.

It is apparent that many have tried to cross: Deflated rafts appear sporadically but regularly along the U.S. side of the river, although given the slow current and narrow nature of the river, it is easily swimmable for a healthy adult.

In that regard, a large levee that sits along a part of the river acts as a virtual wall for a stretch. Occasional heavy rains, and releases of water from dams upstream, have made those levees a necessity. Additional levee walls could serve a double purpose, acting as both flood control and an entry deterrent.

It should be noted that the Border Patrol Agents are not alone in their efforts to stop illicit cross-river trade. The troopers on the Texas Highway Patrol boats (which according to Fox News are "outfitted with bullet-proof panels, fully automatic machine guns and 900-horsepower engines") have authority to ensure compliance with navigation laws, requirements smugglers reportedly usually fail to obey.

Other state troopers patrol the highway and side streets in the RGV, as do local police and the sheriff's department. In addition, Cortina units, composed of one Texas Department of Public Safety officer and one Border Patrol Agent, run regular patrols. Each brings his or her own law-enforcement authority to the often-uncertain conflicts and encounters that occur in the RGV.

In addition, blimps from the Tethered Aerostat Radar System, or TARS, float 10,000 feet above the area, and I spotted at least two of the TARS between Mission and Rio Grande City.

The landscape changes as you ride down U.S. 83 from McAllen to Roma. Largely absent are the chain restaurants and stores that fill the landscape to the east, replaced by any number of used-car and used-tire stores, road-side "carwashes" (consisting of a shed and a hand-held power washer open to the highway), ice-cream and candy kiosks that keep irregular hours, and small restaurants and food stands, in addition to chain gas station/convenience stores. Only a couple of miles separate the river from the highway along this stretch, much of which consists of large undeveloped properties. It is easy to imagine that any number of people in this area may serve as scouts for smuggling operations, but it would be all but impossible to know who.

The modern Border Patrol station in Rio Grande city, east of Roma, is already too small for its force.

On the Ciudad Miguel Alemán side of the river, two people sat on a bench and kept a steady watch at the far bank. Workers on the Mexican side were cutting the small stand of carrizo cane that was growing on the shore. I was told that environmental laws in Mexico do not inhibit eradication of border vegetation, and that the Mexican government cuts the cane to deny cover to smugglers.

In addition to the proximity of this city to the shore, a small island covered in thick vegetation sits in the middle of the river down from the bluff, limiting the distance for smugglers to the U.S. side of the river even more, and providing them with even more cover.

From Roma, I headed 272 miles up the river to Del Rio, in Val Verde County, which presents a different picture of the state of the border. On the way, I passed through Laredo, and saw lines of trucks that were entering the United States to head toward I-35 and onward north. I also passed through Eagle Pass, another prosperous community that has grown up along the river. A local high-school football stadium appeared to have been recently completed, of a size that one would expect to find in a Football Championship Subdivision college or university.

Del Rio itself, however, was not so prosperous. On the way into town, I passed two Border Patrol vehicles, one stationary on the westbound side, and another driving on the eastbound side. As the eastbound vehicle went around a bend, an old man wearing dirty work clothes and leading a horse on the side of the road took out his cellphone and started to make a call.

The town itself looked little improved over the last 40 years. While there were a handful of new hotels and restaurants, the main street was also lined with large glass storefronts, old-line shopping malls, and pawn shops and payday loan offices. The local restaurant where I dined, I was later told, had been opened by a cook who had immigrated from Mexico and worked locally to obtain the capital he needed to open his own restaurant. A relative who had returned to Mexico, however, had reportedly become involved with the cartels and was killed.

My host in Del Rio took me to a ranch on the outskirts of town, beyond the Amistad Reservoir, which straddles the border. The far reaches of the ranch (a 45-minute ride over approximately six miles of largely unimproved roads) overlooked the Rio Grande, where high cliff walls led down to the river on both sides. The rancher grants access to Border Patrol to arrest the few aliens who attempt entry in this largely inaccessible location. Although a boundary fence would likely not prove a greater impediment than the cliffs, additional infrastructure to identify incursions and better access roads would facilitate enforcement.

We next went to a park near where the Pecos River meets the Rio Grande. The scrubland on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande is much lower there, offering much better access to the river. In addition, the Pecos River at the confluence is largely silted in, making the river much easier to ford, and leads to a boat ramp up to the main highway.

Next, we went into the neighborhood of the city that abuts the river. A 1.8-mile border fence, similar in design to the one that surrounds the White House, above an access road along the shore has significantly reduced the incursions, and crime, in the immediately adjacent area. Cross-border burglaries have reportedly occurred, however, in those sections of the town where there is no fencing.