As I mentioned in Part 2, “[b]ecause DHS has apparently already begun ‘shifting to Title 8 removal in advance of the publicly announced May 23’ termination date, the states are now asking the court for an immediate temporary restraining order.” Well, what happened later that day? United States District Court Judge Robert R. Summerhays — the name makes me want to sneeze — from the Western District of Louisiana held a Zoom meeting with the parties and discussed the TRO motion. The meeting minutes state that “[f]or the reasons stated on the record, the Court announced its intent to grant the motion. The parties will confer regarding the specific terms to be contained in the [TRO] and attempt to reach agreement.”

The States’ motion for a TRO is actually quite hilarious in the manner in which it slaps DHS upside the head. A few choice examples (emphases in original):

-

DHS knew the Plaintiff States would be concerned with early partial termination. But DHS nonetheless chose to conceal its actions from the States and this Court. ... [B]y all indications, DHS did not mean for this Court to learn of its furtive early termination ever, and it thus would evade judicial review entirely by the expedient of secrecy precluding judicial scrutiny. ... DHS’s “defense” appears to consist partly of arguing that things could be worse. But the [Administrative Procedure Act, "APA"] has no “we could have acted even more unlawfully” exception. That DHS’s clandestine actions might have been even more flagrantly illegal is hardly the persuasive defense that DHS believes it to be.

-

DHS raises a skeletal, one-sentence ... that the States lack standing, citing only to a Sixth Circuit stay decision. But, apparently forgetting where this Court sits, DHS ignores the Fifth Circuit merits decision making that contention specious.

-

[DHS’s] recycling of that argument — without ever acknowledging its prior loss on this precise issue under binding precedent — is shameless.

-

DHS’s approach calls to mind the discredited “spaghetti approach,” with DHS having “heaved the entire contents of a pot against the wall in hopes that something would stick.”

-

[I]t is notable that in virtually every case the Fifth Circuit has not only rejected the very same argument by DHS, but further specifically cited and distinguished the very same precedents DHS now cites to.

-

That [CDC] Director Walensky purportedly has an incurably closed mind, unsusceptible to any comments she might have received, is not “good cause” under the APA.

-

DHS continues to deny the existence of irreparable harm — and indeed bizarrely castigating ... the States as relying on “rank speculation,” as if its own admissions were not powerful evidence that the States’ arguments were “non-speculative.” ... That is tantamount to gaslighting.

-

[G]iven DHS’s outrageous attempts to hide its actions, a full accounting would ... serv[e] as a powerful deterrent to other agencies similarly tempted to pull equivalent fast ones.

Smoke!

But we have to gird ourselves for the fact that the Title 42 orders are going to go away eventually. The States are just arguing that they shouldn’t go away right now because DHS didn’t adhere to the requirements of the APA, including providing notice and an opportunity to comment, and considering the States’ reliance interests in the continuation of the orders. Even if the States’ legal challenges continue to succeed, DHS can eventually get through the notice and comment process and come up with minimally legally adequate ways to dismiss the States’ reliance interests. And even if the legal challenges continue to succeed, once the D.C. Circuit’s decision goes into effect and the D.C. district court on remand sets forth a process to assure that aliens won’t be returned to persecution, much of Title 42’s value in promoting border security will evaporate.

Thus, we still need to contemplate what a post-Title 42 border will look like and consider what alternatives are out there to curtail the coming super-spreader super-crisis on the border.

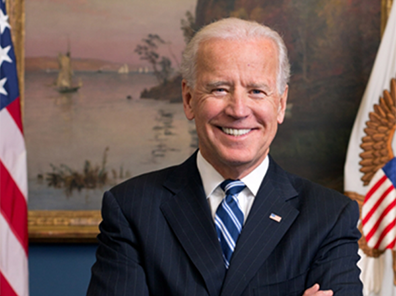

First, the Biden administration needs to go full throttle on the MPP. As I have written:

[The MPP] was wildly successful, in a very real sense being the closest thing we had to a silver bullet to bring the border under control (prior to the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic ...). However, until Covid, the MPP was truly the MVP of border enforcement. It can be so again after our present public health emergency passes if the Biden administration (or a future one) allows it to be. ... [It] can be used to mitigate the most disastrous consequences of curtailing or totally abandoning the use of Title 42.

Second, the Biden administration needs to repromulgate the Trump administration “Security Bars” regulation clarifying that aliens coming from areas where pandemic disease is prevalent can be ineligible for asylum and withholding of removal (both with regards to persecution and with regards to CAT withholding) under the statutory “danger to the security of the U.S.” ineligibilities. Unfortunately, the Biden administration effectively killed the regulation. The administration also needs to repromulgate that part of a (since enjoined) Trump-era regulation relied upon by the Security Bars regulation – requiring that aliens subject to mandatory bars to eligibility for asylum and withholding of removal be found not to have a “credible fear” of persecution or torture and therefore be able to be expeditiously removed (unless qualifying for deferral of removal).

The Security Bars regulation would not (and could not, as it operates within the strictures of Title 8) provide the government the same latitude as does Title 42. However, it possesses distinct advantages over the current Title 8 regulatory practices while being written to be explicitly in compliance with Title 8. In the interests of full disclosure, I participated in the drafting of the regulation.

The Security Bars regulation noted that:

The Departments recognize that, during a pandemic, aliens with otherwise meritorious claims may be subject to the danger to the security of the United States bars. However, it was Congress’s decision to make aliens who there are reasonable grounds for regarding or believing to be a danger to the security of the United States categorically ineligible for asylum and withholding of removal.

As to withholding, the regulation specified two circumstances under which an alien would be subject to the eligibility bar:

-

If a communicable disease has triggered an ongoing declaration of a public health emergency under Federal law ... then an alien is ineligible for withholding of removal ... on the basis of there being reasonable grounds for regarding the alien as a danger to the security of the United States ... if the alien —

(A) Exhibits symptoms indicating that he or she is afflicted with the disease ... or

(B) Has come into contact with the disease within the number of days equivalent to the longest known incubation and contagion period for the disease. -

If, regarding a communicable disease of public health significance ... the Secretary [of Homeland Security] and the Attorney General, in consultation with the Secretary of Health and Human Services, have jointly

(A) Determined that the physical presence in the United States of aliens who are coming from a country or countries ... where such disease is prevalent or epidemic ... would cause a danger to the public health in the United States, and

(B) Designated the foreign country or countries ... and the period of time or circumstances under which they jointly deem it necessary for the public health that aliens or classes of aliens ... who are still within the number of days equivalent to the longest known incubation and contagion period for the disease be regarded as a danger to the security of the United States ... then—

(C) An alien or class of aliens are ineligible for withholding of removal . . . on the basis of there being reasonable grounds for regarding the alien or class of aliens as a danger to the security of the United States ... if the alien or class of aliens are ... regarded as a danger to the security of the United States as provided for [above].

The proposed regulation explained that:

Under current regulations, the bars to [eligibility for] asylum and withholding of removal are generally not applied during the credible fear process. ... [A]liens who establish a credible fear ... despite appearing to be subject to one or more of the mandatory bars ... are nonetheless generally placed in lengthy [removal] proceedings [in immigration court].

Therefore:

-

[T]he Departments are proposing regulatory changes to expedite the processing of certain aliens amendable to expedited removal, including those who potentially have deadly contagious diseases. These changes are necessary because the existing regulatory structure is inadequate to protect the security of the United States and must be updated to allow for the efficient and expeditious removal of aliens subject to the bars to asylum and withholding [who] present a danger to the security of the United States. These bars would be applied at the credible fear screening stage for aliens in expedited removal proceedings, thereby avoiding potentially lengthy periods of detention for aliens awaiting the adjudication of their asylum and withholding claims.

-

[This] is necessary to reduce health and safety dangers to DHS personnel and to the general public. And [it] will ensure a more efficient and expeditious removal process for aliens who will not be eligible to receive asylum or withholding at the conclusion of 240 [removal] proceedings in immigration court.

-

This proposed rule change ... will facilitate removal of aliens subject to the danger to the security of the United States bars as expeditiously as possible during times of pandemic, in order to reduce physical interactions with DHS personnel, other aliens, and the general public.

The final rule did not include this application of the security bars at the credible fear stage because the intervening (and now enjoined) regulation had accomplished this goal for all bars to eligibility for asylum and withholding of removal.

Such aliens would still be eligible for deferral of removal under the CAT regulations if they could demonstrate that it was more likely than not that they would be subject to torture if removed:

This screening standard ... is consistent with DOJ’s longstanding rationale that “aliens ineligible for asylum,” who could only be granted statutory withholding of removal or protection under the CAT regulations, should be subject to a different screening standard corresponding to the higher bar for actually obtaining these forms of protection.

The rule made one important additional change to the credible fear process:

If an alien requests withholding or deferral of removal to his or her home country or another specific country, nothing ... precludes the Department from removing the alien to a third country ... if, after being notified of the identity of the prospective third country of removal and provided an opportunity to demonstrate that he or she is more likely than not to be tortured in that third country, the alien fails to establish that they are more likely than not to be tortured there.

[The regulation] would ... enable DHS to exercise its statutorily authorized discretion about how to process individuals subject to expedited removal who are determined to be ineligible for asylum and withholding of removal based on the danger to security, but who may be eligible for deferral of removal. DHS [would have] the [discretionary] option ... to either place such an alien into 240 [removal] proceedings [in immigration court] or to remove the alien to a country where the alien has not ... established that it is more likely than not that the ... alien would be tortured. This discretion is important because it would give DHS flexibility to quickly process aliens during national health emergencies during which placing an alien into full 240 [removal] proceedings may pose a danger to the health and safety of other aliens with whom the alien is detained, or to DHS officials who come into close contact with the alien.

The security bars regulation would be available for use during the current Covid pandemic, and any future pandemics as well, to provide a Title 8-specific basis upon which to remove aliens making protection claims whose presence in the United States could threaten the public health. Combined with an invigorated MPP, the government would be well positioned to limit the damage to border security caused by the termination of Title 42 authority.