The States’ Lawsuit

As my colleague Andrew Arthur has pointed out, DHS is expecting an unprecedented deluge of as many as 18,000 alien encounters a day at the southern border upon termination of the orders — “equal[ing] out to 6.57 million aliens per year — far beyond any prior record”. This prospect caused the states of Arizona, Missouri, and Louisiana to march to federal court on April 3 to try to block the termination:

This suit challenges an imminent, man-made, self-inflicted calamity: the abrupt elimination of the only safety valve preventing this Administration’s disastrous border policies from devolving into an unmitigated chaos and catastrophe. Specifically, this action challenges the Biden Administration’s revocation of Title 42 border control measures.

…

[T]he Termination Order is not merely unfathomably bad public policy. It is also profoundly illegal. ... Defendants unlawfully flouted the notice-and-comment requirements for rulemaking under the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) ... and [the] Order is arbitrary and capricious, thus violating the APA.

The Complaint asks the court to vacate the termination and enjoin CDC from applying it. [Emphasis in original.]

The complaint (now joined by Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming) asked the court to vacate the termination and enjoin CDC from applying it. Because DHS has apparently already begun “shifting to Title 8 removal in advance of the publicly announced May 23” termination date, the states are now asking the court for an immediate temporary restraining order.

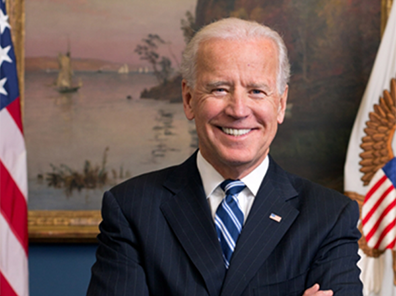

Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt proclaimed that “Title 42 is a crucial tool for controlling the influx of illegal aliens at our Southern border. Time and again, the Biden administration has failed to act to secure our Southern border and h[as] terminated successful programs like Title 42 and the ‘Remain in Mexico’ Policy.” Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry said quite pithily that "Joe Biden needs to stop trying to be woke and start protecting the homeland.”

Alejandro Mayorkas, the secretary of Homeland Security, did try to reassure the American public by proclaiming: “Let me be clear: those unable to establish a legal basis to remain in the United States will be removed” after the termination of the Title 42 orders. The problem with his statement is that it is, in a word, ludicrous. First, Title 8’s expedited removal/credible fear process results in pretty much every illegal alien who wants to being able to establish such a legal basis, at least to the extent that they are found to have a “credible fear” and released into U.S. Second, those who are eventually (years later) ordered removed will largely have absconded and become fugitives. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Commissioner Chris Magnus was more honest: “As a result of the CDC’s termination of its order ... we will likely face an increase in encounters above the current high levels. There are a significant number of individuals who were unable to access the asylum system for the past two years, and who may decide that now is the time to come.”

While this may not necessarily be admissible evidence in the case, if you go to the CBP website and enter “Title 42” in the search function, you will be informed: “We’re sorry — something has gone wrong on our end. What could have caused this?” Yeah, I wonder what could have caused it?

Notice and Comment

The complaint claims that the government “do[es] not deny that the Termination Order would ordinarily be subject to the requirement of providing notice of a proposed rule, taking comment ... and responding to those comments.” Well, not exactly, as the order states that it “is not a rule subject to notice and comment” but that “[e]ven if it were.” In any event, the complaint argues that the defendants “seek to excuse their flouting of that requirement for two reasons: they invoke the ‘good cause’ and ‘foreign affairs’ exceptions. ... But neither applies.”

As to good cause, the CDC argues that:

[T]here is good cause to dispense with prior public notice and the opportunity to comment. ... Given the extraordinary nature of an order .., the resultant restrictions on application for asylum and other immigration processes under Title 8, and the ... requirement that an CDC order ... last no longer than necessary to protect public health, it would be impracticable and contrary to the public interest and immigration laws that apply in the absence of an order ... to [further] delay the effective date of this termination. ... In light of the ... significant disruption of ordinary immigration processing and DHS’s need for time to implement an orderly and safe termination of the order, there is good cause not to delay issuing this termination or to delay the termination of this order past May 23, 2022.

How does the States’s complaint counter this claim? —

CDC had ample time to take public comment on revoking Title 42 and lacks any pressing need or minimally persuasive excuse for failing to do so. President Biden issued an executive order on February 2, 2021, directing CDC and DHS to consider rescinding Title 42. Defendants thus had one day short of fourteen months to take public comment. [Emphasis in original.]

True, but I think the government can successfully argue that the termination is entirely context-based, only appropriate because “public health measures are now available to provide necessary public health protection”. Accordingly, comments solicited or submitted 14 months ago would have long ago been overtaken by the changing facts on the ground regarding the pandemic.

The complaint then argues that:

-

Defendants ignore that while the initial promulgation of Title 42 invoked the good cause exception — because its issuance was during the rapidly unfolding beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic—the same is not true here. ... The exigency of the initial order simply does not exist here. . . .

-

[T]here is a difference between putting in place emergency measures against the backdrop of a rapidly escalating pandemic of epic proportions versus taking action in the context of a slowly dissipating pandemic — it may be an emergency at the start of the pandemic, when quick action is needed, but not when it is tapering off slowly at a predictable pace.” [Emphasis in original.]

If I had been tasked with writing the states’ complaint, I would not have said this! The states are seemingly admitting, even trumpeting, the fact that the Covid-based public health emergency is no more. Given that the entire legal basis for instituting the orders was the existence of such an emergency, the states seem to be undercutting their case. In any event, the complaint then argues that:

[T]he CDC ignores that it did take public comment on the initial Title 42 Order under the Trump Administration, from March 24 to April 24, 2022, and then issued a final rule less than five months after the comment period closed. ... There is no reason that the CDC could not have taken the same approach again here — and the CDC certainly does not supply any. [Emphasis in original.]

Actually, what the CDC sought comment on was not the order, but an interim final rule to deal with future pandemics because existing regulations did “not address the suspension of the introduction of persons into the United States.”

Anyway, the complaint then posits that:

The CDC is ... simply wrong in contending that the “extraordinary nature” of Title 42 orders necessarily eliminates the APA’s requirement for taking public comment. ... [T]he CDC’s arrogant assertion that there is no value to be had from public commenting does not constitute “good cause.” [Emphasis in original.]

Here, the complaint is spot on. The CDC’s arguments make no sense. Why is a public comment period of 30 or 60 days impractical? While it is certainly true that Title 42 processing is contrary to the immigration laws that apply in the absence of an order, there is an order, so one can just as easily argue that the immigration laws that apply in the absence of an order are contrary to the order! Is there a significant disruption — more a suspension — of ordinary immigration processing? Yes, but so what? DHS needs time to implement an orderly and safe termination of the order? Wouldn’t a public comment period give it more time to do so? And, last but not least, giving the public an opportunity to comment is against the public interest? Yeah, I think the complaint accurately pegged the assertion as arrogant.

As to the foreign affairs exception, the termination order states that:

[T]his Order concerns ongoing discussions with Canada, Mexico, and other countries regarding immigration and how best to control COVID-19 transmission over shared borders and therefore directly “involve[s] ... a ... foreign affairs function of the United States;” thus, notice and comment are not required.

The complaint counters that:

The “foreign affairs exception applies in the immigration context only when ... taking public comment ... will provoke definitely undesirable international consequences.” ... But the CDC does not [even] identify any potential “undesirable international consequences[,”] merely allud[ing] to the fact that the Administration is engaged in unspecified talks with Canada and Mexico about Covid-19. That is woefully insufficient. The Administration cannot evade notice-and-comment requirements by the expedient of simply talking with its neighboring countries about the same subject in lieu of seeking comment from its own citizens. [Emphasis in original.]

Again, the complaint is spot on. The CDC’s argument would earn a failing grade in a basic administrative procedure class.

OK, but as to both the good cause and foreign affairs exceptions, I feel duty-bound to admit that the CDC made the exact same arguments during the Trump administration:

This Order is not a rule subject to notice and comment. ... because there is good cause to dispense with prior public notice and the opportunity to comment on this Order [and the foreign affairs exception applies]. ... Given the public health emergency caused by COVID–19, it would be impracticable and contrary to public health practices — and, by extension, the public interest — to delay the issuing and effective date of this Order. In addition, because this Order concerns the ongoing discussions with Canada and Mexico on how best to control COVID–19 transmission over our shared border, it directly “involve[s] ... a ... foreign affairs function of the United States.

Arbitrary and Capricious

The complaint argues that:

The Termination Order also violates the APA as arbitrary and capricious decisionmaking. “[A]gency action is lawful only if it rests on a consideration of the relevant factors” and considers all “important aspects of the problem.”... The CDC’s Order ... expressly refuses to analyze the impacts it will have upon the States. That is, after all, an “important aspect of the problem.” ... Indeed, the Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized “the importance of immigration policy to the States,” particularly as the States “bear[] many of the consequences of unlawful immigration.[”] ... The CDC does not even attempt to deny that its Title 42 Termination Order will impose enormous costs upon the States. [Emphasis added.]

The complaint goes on:

-

The CDC has no license to inflict wanton harms on the States without at least first considering what the magnitude of those harms might be and whether they could be mitigated if the agency considered alternatives with those harms in mind.”

-

Defendants’ unlawful termination of the Title 42 policy will induce a significant increase of illegal immigration into the United States. ... This predicted influx will injure the Plaintiff States in multiple ways, including through increased expenditures on health care, education, and law enforcement, as well as through increased numbers of crimes.

-

Immigration ‘ha[s] a discernable impact on traditional state concerns,’ considering that “unchecked unlawful migration might impair the State’s economy generally, or the State’s ability to provide some important service.”

The complaint cites a recent federal court decision in Ohio:

[W]hen DHS ... “gave no explanation of how its policy ... might increase state criminal justice expenses,” the Southern District of Ohio recently found that DHS had “‘entirely failed to consider’ an important consequence of its policy,” and its rule was therefore arbitrary and capricious.

My colleague Andrew Arthur has incisively analyzed the decision, which enjoined DHS guidance strictly limiting immigration enforcement against criminal aliens.

The complaint also argues that “Defendants failed adequately to consider the spread of infection in DHS facilities resulting from Title 42 termination, because the INA requires that aliens awaiting removal proceedings must be detained.” Well, whether the CDC’s analysis holds up under scrutiny or not, it did consider the impact on congregate facilities, as mentioned previously.

Just a few days ago, the State of Texas filed a separate lawsuit seeking injunctive relief against the termination. Texas’s complaint makes the compelling point that the termination order is arbitrary and capricious simply because of its unexplained inconsistency with other ongoing CDC COVID-19 mandates:

On[]e stark inconsistency is DHS’s wholesale termination of the Title 42 program while maintaining a . . . proof-of-immunity regime for lawful international travelers. COVID-19 cannot pose such a substantial threat to public health that it requires those legally entering the United States to furnish proof of vaccination or immunity upon demand—on penalty of being immediately sent back whence they came—while simultaneously allowing illegal entrants access to the country without even evidence of a negative test

Reliance

CDC Chief of Staff Berger argues that:

-

“Th[e] Termination will be implemented on May 23, 2022, to enable ... DHS ... to implement appropriate COVID-19 mitigation protocols, such as scaling up a program to provide COVID-19 vaccinations to migrants, and prepare for full resumption of regular migration processing under Title 8 authorities.

-

CDC has determined that no state or local government could be said to have legitimately relied on the CDC Orders ... because those orders are, by their very nature, short-term orders, authorized only when specified statutory criteria are met, and subject to change at any time in response to an evolving public health crisis.

-

CDC is not aware of any reasonable or legitimate reliance on ... continued expulsion ... beyond potentially local healthcare systems’ allocation of resources, which CDC has considered. ... Even if a state or local government had relied on the continued existence of a CDC order[, the statute] only authorizes CDC to prevent the introduction of noncitizens when it is required in the interest of public health. No state or local government could reasonably rely on CDC’s continued application of Section 265 once CDC determined that there is no longer sufficient public health risk. ... CDC’s considered judgment is that any reliance interest that might be said to exist ... is not weighty enough to displace CDC’s determination that there is no public health justification for such a suspension at this time.

-

[T]he effective date of this Termination has been set for 52 days from the date of issuance, thus providing state and local governments time to adjust.

-

Finally, the CDC Orders ... are not, and do not purport to be, policy decisions about controlling immigration; rather [they] depend[] on the existence of a public health need. Thus, to the extent that state and local governments ... were relying on an order ... as a means of controlling immigration, such reliance would not be reasonable or legitimate.

The complaint counters that:

-

[T]he ... Order is arbitrary and capricious because the Defendants did not consider Plaintiffs States’ reliance interests in the continuation of the Title 42 policy. ... [in] whether States relied on continuation of the ... policy when [they] determined how they would marshal and distribute their resources to address the public-health, safety, and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as their decisions about resource allocations to deal with the number of unauthorized aliens entering their states.

-

The ... Order offers no explanation ... of how 53 days might be enough time for states . . . when the Title 42 policy has been in place for more than two years and when Defendants have ... [left] Title 42 as the only remaining bulwark against the rising flood of migrants pouring across the border illegally. The ... Order ... utterly ignores Plaintiffs’ reliance interests.

-

[E]ven if the CDC were correct that the ‘short-term’ nature of the ... Orders ... meant that the States could rely on the Orders being in place permanently, the States still could reasonably rely on the CDC not to revoke the Orders abruptly at a truly terrible time to do so. The Order’s timing will greatly exacerbate an already extant meltdown of operational control at the southern border — which even the Administration and its supporters fully expect. ... Simply put, the States could reasonably rely on the CDC not suddenly revoking its Title 42 Orders now.” [Emphasis added.]

Overall, I would have to agree with the CDC, because the sole statutory basis for the establishment and continuation of a Title 42 order is “to avert [the] danger [of the introduction of a communicable disease], and for such period of time ... necessary for such purpose” — except for two things. First, the CDC itself admits that it has the power to delay termination at least in part for reasons having nothing to do with public health concerns (Emphases mine):

-

Th[e] Termination will be implemented on May 23, 2022, to enable ... DHS ... to implement appropriate COVID-19 mitigation protocols, such as scaling up a program to provide COVID-19 vaccinations to migrants, and prepare for full resumption of regular migration processing under Title 8 authorities.

-

Based on DHS’ recommendation and in order to provide DHS time to implement operational plans for fully resuming Title 8 processing, including incorporating appropriate COVID-19 measures, this Termination will be implemented on May 23, 2022.

-

Putting [DHS’] plans in place, ensuring that the workforce is adequately and appropriate trained for their shifting roles, and deploying critical resources require time. This Termination will be implemented on May 23, 2022, to provide DHS with additional time to ready such operational plans and prepare for full resumption of regular migration under Title 8.

The complaint recognizes this admission by the CDC:

By delaying the effective date ... Defendants ... recognize ... that they have the authority and capacity to delay the Termination Order to account for immigration-related consequences. But they failed to analyze whether they should exercise that authority in a different manner given the enormous immigration consequences that even they predict will occur. [Emphasis added.]

Second, the Supreme Court’s DACA decision (DHS v. Regents of the Univ. of California) dealt a heavy blow to CDC’s dismissal of the states’ reliance interests. As Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the majority:

When an agency changes course ... it must “be cognizant that longstanding policies may have ‘engendered serious reliance interests that must be taken into account.’” ... “It would be arbitrary and capricious to ignore such matters.” ... [T]he Government does not contend that [the Acting DHS Secretary] considered potential reliance interests; it counters that she did not need to. In the Government’s view ... DACA recipients have no “legally cognizable reliance interests” because the DACA Memorandum stated that the program “conferred no substantive rights” and provided benefits only in two-year increments. ... But ... the government ... [doesn’t] cite[] any legal authority establishing that such features automatically preclude reliance interests, and we are not aware of any. These disclaimers are surely pertinent in considering the strength of any reliance interests, but that consideration must be undertaken by the agency in the first instance, subject to normal APA review

Here, the CDC similarly claims that it does not have to consider any reliance interests of the states because none are legitimate — CDC’s orders were only “short term”.

The Court goes on:

-

[The government] might conclude that reliance interests in benefits that it views as unlawful are entitled to no or diminished weight.

-

[The] Acting Secretary ... authorized DHS to process two-year renewals for those DACA recipients whose benefits were set to expire within six months. But [her] consideration was solely for the purpose of assisting the agency in dealing with “administrative complexities. ... She should have considered whether she had similar flexibility in addressing any reliance interests of DACA recipients. The lead dissent contends that accommodating such interests would be ‘another exercise of unlawful power,” ... but the Government does not make that argument and DHS has already extended benefits for purposes [of such administrative complexities], following consultation with the Office of the Attorney General.

-

In [the dissent’s] view, DACA is illegal, so any actions under DACA are themselves illegal. Such actions, it argues, must cease immediately and the APA should not be construed to impede that result.

-

The dissent is correct that DACA was rescinded because of the Attorney General’s illegality determination. ... But nothing about that determination foreclosed or even addressed the option[] of ... accommodating ... particular reliance interests. [The] Acting Secretary ... should have considered th[is] but did not. That failure was arbitrary and capricious in violation of the APA.

Here, even if it might be considered unlawful for the CDC to consider border security or other issues not tied to averting the danger of the introduction of a communicable disease when instituting or extending a Title 42 order, the Supreme Court has seemingly ruled that federal agencies must consider accommodating reliance interests emanating from such unlawful considerations, especially in cases like the present, where the CDC has already delayed termination for reasons having nothing to do with averting the danger of the introduction of a communicable disease.

The court goes on:

Had [the Acting Director] considered reliance interests, she might ... have considered a broader renewal period based on the need for DACA recipients to reorder their affairs [or] more accommodating termination dates for recipients caught in the middle of a time-bounded commitment, to allow them to, say, graduate from their course of study, complete their military service, or finish a medical treatment regimen.

Here, the complaint asks why the states could not reasonably rely on the CDC “not to revoke the orders abruptly at a truly terrible time to do so.” The Supreme Court seemingly would ask the CDC the same question.

In light of DHS v. Regents of the Univ. of California, it seems that the states have a realistic change of prevailing on their APA reliance claims.

Title 42’s Future in the Courts Looks Uncertain

Even if the Biden administration had not abandoned Title 42, and putting aside APA issues for the moment, the future of Title 42 border expulsions looks uncertain in the federal courts. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals recently issued a decision in Huisha-Huisha v. Mayorkas that, if not overturned by the Supreme Court, could render Title 42 impotent. And the decision was authored by Justin Walker, a Trump appointee!

The court refused to fully uphold a district court’s preliminary injunction against Title 42 expulsions. However, it was a pyrrhic victory for Title 42. The court ruled that § 265 “probably” allows the government to expel aliens, but with the caveat that it can’t expel them to a country where they would be threatened with persecution or torture. The court then remanded the case to the district court for ultimate resolution of the merits.

The D.C. Circuit’s three-judge panel foreshadowed the CDC’s termination decision when it stated that “Of course, ‘the public has a strong interest in combating the spread of’ COVID-19. ... But this is March 2022, not March 2020. The CDC's ... order looks in certain respects like a relic from an era with no vaccines, scarce testing, few therapeutics, and little certainty.”

The D.C. Circuit then found that:

-

The Plaintiffs ... argue that expulsions under § 265 are illegal. We disagree, at least at this stage of the case. We find it likely that aliens covered by a valid § 265 order have no right to be in the United States, and the Executive can immediately expel them.

-

Two statutes — § 265 and § [237](a)(1)(B) [of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)] — appear to provide the Executive with ample authority to expel such aliens. ... The § 265 Order also means covered aliens who enter at this time are here illegally. ... [§ 237](a)(1)(B) says, “Any alien who is present in the United States in violation of ... any ... law of the United States ... is deportable.” ... That means, barring any exceptions Congress creates elsewhere, the Executive can expel aliens who are here illegally.

-

But § 265 does not tell the Executive where to expel aliens. ... Title 8 lists several possible destinations [and] adds that the Executive cannot remove aliens to a country where their ‘life or freedom would be threatened’ on account of their “race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion [commonly referred to as ‘withholding of removal’].” ... And it prohibits the Executive from expelling aliens to a country where they will likely be tortured [commonly referred to as CAT relief]. [Emphasis in original.]

-

[The INA] provides aliens with ... substantive rights to resist expulsion ... includ[ing] ... asylum, withholding of removal, and protections under [CAT].

-

[The asylum statute] entitles aliens — even those who enter ... illegally — to apply for asylum. ... According to the Plaintiffs, the Executive violates [this provision] when it expels aliens before allowing them [this] opportunity. ... That argument deserves attention from the District Court. ... It may be the closest question in this case. But on its merits, at this stage of the litigation, the Plaintiffs have not shown they are likely to succeed.

“In normal times — when the Executive has not invoked § 265 — the Plaintiffs are of course correct about [aliens’ entitlement to apply for asylum]. So the question is how, if at all, we can reconcile [the two statutes]. [The court then cites a Supreme Court ruling that] when a court is “confronted with two Acts of Congress allegedly touching on the same topic,” the court must “strive to give effect to both” [and a book by former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia stating] “The provisions of a text should be interpreted in a way that renders them compatible, not contradictory.”

...

The best reconciliation of the two statutes is based on the discretionary nature of asylum. The Executive "may grant asylum." ... Or it may not. ... And here, for public-health reasons, the Executive has shown an intent to exercise that "discretion" by foreclosing asylum for the specific subset of border crossers covered by its ... Order.

It's true that the ... Order forecloses more than just a grant of asylum; it also forecloses the . . . procedures that aliens use to apply for asylum. But if the asylum decision has already been made — by the ... Order — then those procedures would be futile. [Emphasis added.]

-

“[W]ithholding of removal]” precludes the Executive from removing aliens to places where they will likely be persecuted [and] relief under the [CAT] precludes the[ir] removal ... to places where they will likely be tortured.

The Plaintiffs argue that the ... Order violates those two limits on where the executive can expel aliens. On that question, the Plaintiffs have shown they are likely to succeed on the merits. [Emphasis added.]

-

[W]ithholding-of-removal relief ... is mandatory. ... In other words, unlike [asylum, it] gives the Executive no discretion ...

[T]o expel aliens to places prohibited ... the Executive must identify a statute that creates an exception. ... It says § 265 is that statute. But we see no conflict between [the two].

[Section 265] says nothing about where the Executive may expel aliens.

...

[W]e can give effect to both statutes. And because we can, we must. ... That leaves the Executive with the power to expel [aliens] to ... any place where the[y] will not be persecuted [or tortured]. [Emphasis added.]

-

The Executive argues that § 265 permits it to suspend [§ 241 of the INA’s] ... limits on where the Executive can expel aliens. It relies on § 265’s reference to “a suspension of the right to introduce.”

But § [241] does not give aliens a “right to introduce” for § 265 to suspend. Its protections do not permit aliens to enter the country. ... Instead, § [241] governs where the Executive can expel aliens.

...

The Plaintiffs have shown they are likely to succeed on the merits of their claim that § [241] limits where the Executive can expel aliens who violate the § 265 Order.

...

[I]t does [not] curb the Executive's power to expel them to a country where they will not be persecuted or tortured. [Emphasis added.]

Why do I consider the decision a pyrrhic victory for expulsions? First, because it lets me use the term pyrrhic victory multiple times in this blog post. Second, because the district court on remand will almost certainly conclude that if aliens can’t be returned to countries where they are threatened with persecution or torture, the only way to ensure this is to require DHS to use the very same debased expedited removal/credible fear procedures that had led to the pre-MPP/pre-Covid crisis at our southern border. These procedures resulted in a situation where:

United States officials ... each day encountered an average of approximately 2,000 inadmissible aliens at the southern border [and] large caravans of thousands of aliens, primarily from Central America, [were] attempting to make their way to the United States, with the apparent intent of seeking asylum after entering the United States unlawfully or without proper documentation.

Needless to say, the D.C. Circuit was trying to be too cute, and got it wrong. First, the decision throws around the terms “expel” and “expulsion” as if they are indistinguishable from the Title 8 term “removal”, which is not the case. DHS latched onto “expel” and “expulsion” for the very purpose of distinguishing the prohibition of the introduction of aliens pursuant to Title 42 from the removal of aliens under Title 8. In all of Title 8, “expel” and “expulsion” are only used in a handful of places, such as:

It shall be the policy of the United States not to expel, extradite, or otherwise effect the involuntary return of any person to a country in which there are substantial grounds for believing the person would be in danger of being subjected to torture. [Emphasis added.]

And

The term “immigration laws” includes ... all laws ... relating to the immigration, exclusion, deportation, expulsion, or removal of aliens. [Emphasis added.]

Even in these instances, it is not immediately clear as to what the terms are referring. Conversely, § 265 of Title 42 never even uses “expel” or “expulsion.” It utilizes “introduce”, which is never found in the immigration laws with this meaning. Why is any of this important? It is important because the “removal” in withholding of removal is only referring to a removal under § 240 of the INA, which describes removal proceedings in immigration court — § 240(a)(3) provides that:

Unless otherwise specified in this chapter, a proceeding under this section shall be the sole and exclusive procedure for determining whether an alien may be admitted to the United States or, if the alien has been so admitted, removed from the United States. [Emphasis added.]

Nothing in “the chapter” refers to Title 42. Thus, when the withholding of removal statute provides that the government cannot “remove an alien to a country”, it is by necessity not referring to Title 42 expulsions. Such expulsions, or whatever you want to call the prohibition on the introduction of certain persons, are not removals in so far as they pertain to withhold of removal. Thus, it is simply not the case, as the D.C. Circuit believes it to be, that “§ [241] limits where the Executive can expel aliens who violate the § 265 Order.”

The government in essence made this argument in litigation over the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP). In the 9th Circuit’s case of Innovation Law Lab v. Wolf:

The Government ... argues ... that § [241(b)(3)(A) of the INA, the withholding of removal statute] does not encompass a general antirefoulement obligation. It argues that the protection provided ... applies to aliens only after they have been ordered removed to their home country at the conclusion of a regular § 240 removal proceeding [in immigration court]. ... It writes ... [that a]liens subject to MPP do not receive a final order of removal to their home country when they are returned (temporarily) to Mexico, and so there is no reason why the same procedures would apply.

Now, it is true that the 9th Circuit rejected the government’s argument:

The Government reads [the statute] too narrowly. ... [I]ts application is not limited to such [removal] proceedings. ... [A]s recognized by the Supreme Court, Congress intended [withholding of removal] to “parallel” Article 33 of the 1951 [Refugee] Convention. ... Article 33 is a general anti-refoulement provision, applicable whenever an alien might be returned to a country where his or her life or freedom might be threatened on account of a protected ground. ... not limited to instances in which an alien has had a full removal hearing.

But the 9th Circuit is wrong (as the Supreme Court would likely have recognized had the Biden administration not tried to jettison the MPP). It needs to read § 240(a)(3), which was later enacted.

Second, the D.C. Circuit is wrong because it demonstrates absolutely no understanding of the realities of border enforcement. It states that:

The Executive also speculates about a risk of COVID-19 spreading from aliens held in congregate settings to the general public. But ... the preliminary injunction affirmed here does not require "catch and release." It does not bar the Executive from detaining covered aliens until they can be expelled. It only requires the Executive to refrain from expelling them to a place where they will likely be persecuted or tortured. And through an expedited removal process enacted by Congress in 1996, the Executive can quickly expel aliens with non-credible claims for relief. [Emphasis added.]

As I noted earlier, Title 8’s expedited removal/credible fear process results in pretty much every illegal alien who wants to being able to establish a “credible” claim for relief. They cannot be “quickly” expelled.

Third, the D.C. Circuit gets it wrong because it believes that the CDC’s order does not “serve[] any purpose”:

We are not cavalier about the risks of COVID-19. And we would be sensitive to declarations in the record by CDC officials testifying to the efficacy of the ... Order. But there are none. ... [F]rom a public-health perspective, based on the limited record before us, it's far from clear that the CDC's order serves any purpose. [Emphasis added.]

The court apparently missed the CDC’s conclusion in October 2020 that:

The risks of COVID–19 transmission and overutilization in community hospitals serving domestic populations would have been greater absent the ... Order[, which also] reduced the risk of COVID–19 transmission in POEs and Border Patrol stations, and thereby reduced risks to DHS personnel and the U.S. health care system. The public health risks to the DHS workforce — and the erosion of DHS operational capacity — would have been greater absent the ... Order. [T]he ... Order has significantly reduced the population of covered aliens held in congregate settings in POEs and Border Patrol stations, thereby reducing the risk of COVID–19 transmission for DHS personnel and others within these facilities.

Well, who knows, maybe the Biden administration “forgot” to include this in the administrative record of the case.

One can hope that the Supreme Court will eventually correct the D.C. Circuit.

Unsolicited Advice

The Biden administration will find itself in a pickle if it decides to reverse (or delay) the CDC’s termination decision for electoral reasons. As discussed, the sole statutory rationale for the utilization of Title 42 is to avert the introduction of a communicable disease into the U.S., and for such period of time as necessary for this purpose. But the CDC has already concluded that “there is no longer a serious danger that the entry of covered noncitizens . . . will result in the introduction, transmission, and spread of COVID-19 and . . . a suspension of the introduction of [the] noncitizens is no longer required in the interest of public health.” Three years ago, the Supreme Court ruled in Dept. of Commerce v. N.Y. that (at least sometimes) “pretextual” decision-making can violate the APA:

[H]ere the ... the sole stated reason ... seems to have been contrived. We are presented, in other words, with an explanation for agency action that is incongruent with what the record reveals about the agency’s priorities and decisionmaking process. ... [W]e cannot ignore the disconnect. ... Our review is deferential, but we are “not required to exhibit a naiveté from which ordinary citizens are free.” ... The reasoned explanation requirement of administrative law, after all, is meant to ensure that agencies offer genuine justifications for important decisions. ... Accepting contrived reasons would defeat th[is] purpose. ... If judicial review is to be more than an empty ritual, it must demand something better. ... Reasoned decisionmaking under the [APA] calls for an explanation for agency action.

So, what is the White House/CDC to do should perchance they want to avoid further exacerbating the current border calamity (for reasons noble or ignoble)? Unless the CDC is going to argue that its termination decision (only a few weeks old) was in error, how will it justify a policy reversal? My unsolicited advice would be to take a page from the complaint filed by Arizona, Missouri, and Louisiana. Assert that you are delaying termination because, upon reflection, you realize the states have a point about their reliance interests. You realize that they could reasonably rely on you not abruptly revoking the orders at a truly terrible time to do so, a revocation that would greatly exacerbate an already extant meltdown of operational control at the southern border that you fully expect.