"Most Americans, and many of my colleagues, will be surprised to know that there is no firm limit on the number of immigrants that can be admitted to the United States each year. For the past 15 years, the number of immigrants admitted for permanent residence has increased in all but 3 years. In effect the number of immigrants coming to the United States each year is governed, not by the laws of the U.S., but by the desires of the immigrants themselves."

- Senator Alan Simpson, Congressional Record, August 6, 1993

Introduction

The U.S. Congress currently has before it a measure that would reduce substantially the level of annual legal immigration. This focus on legal immigration comes at a time that Congress and the administration are also looking at ways to decrease illegal immigration. The bill, recently introduced by Senator Harry Reid (D-NV) would reduce annual immigration to 300,000. Earlier recommendations have been to limit immigration to other target levels, such as 400,000 (the target of the Rockefeller Commission in 1972), or "zero net immigration" meaning immigration equal to emigration. The reasons for reducing immigration from its current high level (over 800 thousand last year not counting additional hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants) relate primarily to our nation's current rapid population growth, and the need to harness our workforce to a high-wage, high-skill economy that is internationally competitive.

Reducing legal immigration could be achieved by setting an overall ceiling, as Senator Reid has proposed, or in piecemeal fashion under various of the legal immigration categories the opposite of what Congress did in 1990 when it last raised immigration levels. An alternative approach might focus directly on the relationship between the amount of immigration and its impact on the overall population size.

Central to any consideration of reducing legal immigration and for evaluating reduction proposals is an understanding of the magnitude of the current level of immigration, on what basis are newcomers being admitted, how many are coming in the different categories, and what would be the implications of a reduction in the flow. Using 1992 immigration levels and illustrative reductions, this paper demonstrates how a major cut back in legal immigration might be accomplished. The results of the analytical look at the composition of current immigration are then compared to actual reduction proposals, including the Reid bill.

The Population/Immigration Connection

...the U.S. population in the year 2000 is projected to be 8.8 million (3.3 percent) larger than it would have been if there had been no net immigration after July 1, 1991. This figure would increase to 21 million by 2010, and 49 million by 2030. By the middle of the next century, the U.S. population may include 82 million post-1991 immigrants and their descendants, or 21 percent of the population. As natural increase declines, the compounding impact of immigration on the U.S. population growth would increase each year. In 1992, about 33 percent of the growth in the population would be caused by net immigration. By the turn of the century, net immigration would account for over 60 percent of the post-1991 population increase. Eventually, about 93 percent of the population growth during the year 2050 may be due to post-1991 net immigration.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P-25-1092, GPO, December 1992

The Census Bureau thus explained in its 1992 "middle level" population projection the linkage between current immigration and U.S. population growth. Today more than one-third of population growth is attributable to immigration, and that share will progressively get closer to one hundred percent (see appendix). The other factors influencing population growth are fertility of our population (currently about replacement level), and net migration to the United States by citizens living abroad. Population increase is offset by normal mortality and emigration of U.S. citizens and residents for residence abroad.

Many organizations now advocate either a stable, "no-growth" population policy or a reduction in population to bring our size into balance with resource consumption levels that may be sustainable in the future. Others have called for a moratorium on immigration pending adoption of reduced limits.

Could we adopt a "zero net immigration" policy? This concept implies immigration equal to emigration which the Census Bureau currently estimated to be between 100,000 and 260,000, with the middle estimate at 160,000. would decreasing the intake of newcomers represent major political costs in terms of interest groups that would be affected or in terms of objective national needs?

The challenge for those who would reduce immigration is to explain what it is that they want a U.S. immigration policy to achieve. To answer these questions requires an understanding of the component elements of current immigration admission practice.

Current Immigration Levels

More than 1200000 foreigners entered the Untied States last year as permanent settlers. Included among these newcomers were an estimated 300,000 illegal immigrants. Also included in that total were as many as 80,000 aliens who entered or remained in the country by requesting protection under our provision for asylum, even though they are never determined to be eligible or are found ineligible for that status. The encouraging efforts to reduce illegal immigration and asylum abuse that are underway in Congress with the support of the administration are outside the scope of this paper.

Included in the current over 800,000 level of annual legal immigration is a broad array of entry categories. Most admissions fall into the rubrics of family reunification, refugees and asylees, or job-related entry. The relative size of immigration admissions in each of the three general categories in 1992 was: family-related: 61 percent; refugees and asylees: 19 percent; employment-related: 15 percent; other: 5 percent.

Refugees and Asylees

The United States is now admitting over a quarter of a million refugees and asylees each year. When the Refugee Act was adopted in 1980, it was contemplated that refugee immigration from all sources would not be over 50,000 per year. Many of the entrants under the asylum provision are abusers of the process and rightfully considered illegal immigrants rather than refugees. These numbers hopefully will drop as a result of current reform efforts. But refugees, who will not be affected by asylum reform efforts, and legitimate asylum seekers accounted for about 170,000 of last year's immigrants.

Refugee newcomers today tend most often to be from the Third World. In FY 1992, over eighty percent of the refugees in the resettlement program were from East Asia. Only about five percent were from Europe. The current refugees are less likely to bring education and work skills that will facilitate a quick transition to self-support, and unlike earlier periods of refugee flows from Europe, they are less likely to have relatives to join. They, therefore, are more likely to become a burden on the taxpayer, frequently at the state and local levels when federal transition funding runs out.

The United States accepts more refugees for resettlement by far than any other country. Yet our program represents only a drop in the bucket compared to U.N. estimates of 18 million refugees in the world today. We have been generous in accepting refugees from areas where we have been militarily involved, e.g., Southeast Asia. For example, last year's immigration statistics include Amer-asian children who have been admitted as if they were refugees, even though they are not. Cuba and the former Soviet bloc have been other sources of major intake. Because of the rapid, profound political changes taking place around the world in the post-Cold War environment, it would seem that this program should be reviewed with the objective of attempting to establish a firm ceiling to entries on a non-discriminatory basis. A major reduction from current entry levels would not require a change in the law, only an agreement between the legislative and executive branches.

There are good reasons why such a reduction might, in fact, be in the best interest of refugees. The first has to do with the refugee resettlement program in the United States. Not all those who would like to be settled in the United States can be, so our focus should be on how to make sure that those who are accepted are given the best chance for a successful transition to a new life in this country. The other reason relates to a focus on those who cannot be resettled in the United States and how we might best focus our assistance to help them survive their period as refugees until they can be resettled in their home country.

Because there is currently no firm ceiling on refugee admissions and the decision making process on intake levels is divorced from the process of funding transitional support programs for the new refugees, the federal funding level to support the settlement and adjustment of the refugee influx has not kept pace. This has meant that the funding level per refugee has been consistently decreasing. If the number of refugees was scaled to the 50,000 level contemplated in the 1980 legislation, for example, the funding level would not run out before the refugees have had a chance to learn English and workplace skills that are intended to prepare them to become self-supporting. Such a change would also diminish the current inequitable impact of the refugee program on the states that receive the largest numbers, e.g., California and Florida. At present, when the federal support funds are exhausted after eight months (rather than the three years originally contemplated in the legislation), the states are left holding the bag for support services paid out of state funds.

With the knowledge that the vast majority of refugees will never be resettled, the United Nations and others have called for an allocation of scarce refugee funding to be channeled to the basic shelter and feeding needs of the refugees in UN-run camps as near as possible to their home countries. When conditions permit, the refugees are then assisted by the UN in repatriation programs to return home. Since the bulk of refugees come from Third World countries and seek refuge in neighboring countries, there is no doubt that international resources can stretch farther in support programs if directed toward these UN programs. That is the thrust of the recommendation by a recent Trilateral Commission report on refugees authored by Doris Meissner, the Immigration Service Commissioner-delegate.

To achieve and maintain a reduction, Congress must set an unbreachable ceiling on refugee and asylee resettlement. Otherwise the combined special pleadings for exceptional treatment will lead to an ever-expanding admissions policy, as experienced with the 1980 Refugee Act.

If this were done, emergency refugee situations would then require a U.S. response abroad, or, if that were not feasible, by temporary measures in the U.S. intake of refugees. Rather than provide for a breachable ceiling on refugee admissions, however, temporary increases could be accommodated by providing the President authority to reallocate immigration numbers from other categories.

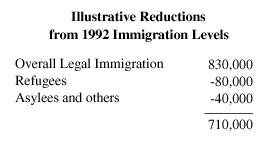

If the refugee and asylum entry categories were reduced to 50,000 the level contemplated in the current law, and a decrease of about 120,000 from the 1992 level annual legal immigration would be reduced from about 830,000 to about 710,000.

Employment-Based Immigration

"The U.S. can either evolve towards a high-technology economy with a labor force of constantly advancing productivity, wage levels, and skills, or it can drift towards a low-technology, low-skill, and low-wage economy, market by widespread job instability and growing income disparity. Immigration policy will be important to the outcome."

- Otis L. Graham, Jr., Professor of History, Rethinking the Purposes of Immigration Policy, 1991.

Job-related immigration accounted for about 120,000 new immigrants in 1992. These are described in the immigration law as aliens with "extraordinary ability," "outstanding professors or researchers," "multinational executives or managers," "professional with advanced degrees," skilled workers, or other workers and their families. Their entry, in most instances, is supposed to relate to shortages of persons with such skills in the United States. If there is need for these persons, does that necessarily mean that such shortages are permanent? Could these persons enter the country as non-immigrants to perform their services until U.S. citizens or resident aliens can be trained for the positions?

The most recent 120,000 level of employment-related immigration is slightly more than double the level before the 1990 Immigration Act increased immigration in this category. During the previous four year period (1988-1991) the average intake in this immigration category was 55,000. If there is agreement that the 1990 increase in legal immigration should be reversed, the 55,000 level could be restored.

With a population of over a quarter billion inhabitants, and with an unemployment rate currently at about seven percent, it is difficult to conceive of a labor shortage that could not be met in the medium or long-term without resorting to immigration. However, it would seem appropriate that any employment-related immigration should be linked to prevailing economic conditions in the United States.

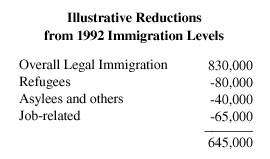

If most of the current job-taking immigrants and accompanying family members (120,000) were reduced to a ceiling of 55,000 per year to meet the most meritorious permanent needs of the nation, the remaining annual intake level would be reduced to about 645,000.

Special Immigrants

There are a number of special immigration provisions. Some relate to persons in residual preference categories, i.e., those who began applications under previous laws. Others apply to "lottery" winners and "special" immigrants such as foreign employees of the U.S. government, former Panama Canal employees, former employees of international organizations who served in the United States, and aliens who served in the U.S. armed forces. Some of the special provisions benefit commercial interests as well as the U.S. Government.

Each of the special admission categories has been established as a result of political pressure and special interest lobbying. However, in the process of a reexamination of categories of admission and their relationship to an overall ceiling, probably none of these categories would be defended by the administration as essential to U.S. national needs.

The number of immigrants admitted in these categories amounted in 1992 to about 40,000. Although there is no current controversy over immigration admissions under these special categories, they too would need to be scrutinized in the process of reducing overall immigration. Under a more limited immigration admissions policy, any continued special entry programs would have to compete with such categories as relatives of U.S. citizens, refugees, or highly-skilled workers. If these people intend to join the work force, they might be expected to meet the test of whether the labor market needs their skills.

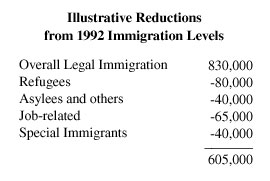

Without these 40,000 immigrants, the annual level of newcomers would be reduced to about 605,000.

Family Reunification

The category that provides for the largest number of immigrants family reunification accounted for about 500,000 immigrants last year. Therefore, any effort to reach an overall level of immigration at or below 400,000 requires a critical look here, too.

Family-related immigration refers to those who can immigrate based on their relationship to a U.S. citizen or a U.S. resident alien. Parents, spouses, and children of U.S. citizens accounted last year for over 235,000 newcomers. Extended family members of citizens adult offspring and siblings and the spouses and children of permanent residents added another 265,000 immigrants last year.

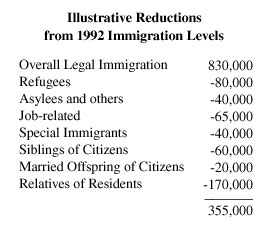

One proposal for reducing the level of family-related immigration considered in the past is to reduce the categories of qualifying family members. If, for example, immigration preference excluded siblings (and their families) or U.S. citizens (about 60,000 last year), this change in the law would also disrupt, to some extend, "chain" immigration whereby a foreign-born U.S. citizen sponsors his or her brothers and sisters plus the brothers' and sisters' spouses, and then the new immigrant spouses may later, upon becoming U.S. citizens, sponsor their family members ad infinitum. "Chain" immigration also would be affected by removing the provision that confers family immigration status on the adult married children of foreign-born U.S. citizens (about 20,000 last year). Does this seem unusually harsh? The United States is the only industrialized country that provides for such non-nuclear family immigration entitlement. If these categories were eliminated, the annual total immigration level could then be reduced by about 525,000.

A more restrictive approach also would eliminate the ability of resident aliens to take advantage of the family reunification provisions. This would not affect the ability of an immigrant to bring in an accompanying or following spouse and children. But it would preclude the ability for a resident alien to sponsor for immigration a spouse or child who were not family members when he or she immigrated to the United States. The U.S. resident would have to become a U.S. citizen prior to sponsoring family reunification immigrants.

Reunification of family members of "green card" holders, i.e. U.S. permanent residents, accounted for about 170,000 immigrants last year. This number includes family members of the 2.7 million persons legalized under the 1986 IRCA. If this family-related provision were eliminated, the remaining annual level of immigration would be reduced to about 355,000. The family reunification system would be significantly narrowed, but without curtailing the interests of U.S. citizens in nuclear family reunification. It would also bring the United States in line with other immigration receiving countries.

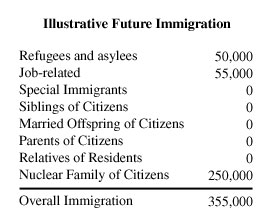

The Bottom Line

The above review of the categories that make up legal immigration demonstrates how these categories might be decreased under a new policy framework if doing so were found to be in the U.S. national interest. It also permits a focus on what intermediate levels are possible if entire classes of immigration were removed. In this approach, the magnitude of reduction possible in any category and the residual entry level that might be retained are arbitrary and are for illustrative purposes. The results of the review show how immigration could be reduced to a bottom line level of 355,000 by eliminating several current categories of immigration and scaling back on others.

Reviewing the makeup of legal immigration serves as a reminder that it is comprised of programs that are, for the most part, entirely discretionary. Some aspects, such as family reunification and admission of refugees have a long history, and therefore, significant momentum behind them. However, they are not written in stone (or even in the U.S. Constitution), and are amenable to expeditious change if there is a consensus to do so.

Although a discussion of reduction in legal immigration by eliminating certain categories of immigration was adopted for the purposes of assisting the focus on the component parts of legal immigration, it would also have merit as a policy framework. It would be a clean-cut approach to reductions, because it would make immigration policy more understandable for the public and for intending immigrants and their sponsors in this country.

Those most inconvenienced by this approach might be immigration lawyers who now benefit from the current convoluted, nearly incomprehensible, and frequently shifting alternative entry provisions. The categories that would constitute the 355,000 level are nuclear family members of U.S. citizens and a reduced level of refugee and employment-based intake. This level would still be significantly in excess of the 160,000 citizens of permanent resident mostly the latter who are estimated by the Census Bureau to abandon the United States each year. A zero net immigration level would not have been achieved, but this level would be considerably less than one-half of the current annual immigrant intake.

It should be noted that because the level of family reunification immigration relates directly to the number of new legal immigrants, as the overall level of immigration diminishes, the level of family reunification immigration will also diminish. A major reduction in legal immigration would have the long-term impact of a corresponding decrease in the associated family reunification immigration. The eventual result would be a reduction to as few as or fewer than the 300,000 ceiling contemplated in the Reid bill.

Alternative Approaches

Reducing immigration by eliminating or significantly restricting categories of immigration is only one way that legal immigration might be reduced. Reduced immigration could be achieved without any major restructuring. Simply reducing the level of refugees could be accomplished by reversing the increases in the 1990 Immigration Act. The most extreme approach, one not currently advocated, would be to close the door entirely to immigration. That concept does not merit much consideration because it is not a politically feasible proposition, nor would it be in the national interest to entirely shut off the possibility of bringing the skills of foreigners to the U.S. workplace.

Alternatively, new approaches have been proposed that would reduce immigration by starting at the macro level that is, establish an overall ceiling and then prioritize the order in which immigrants would be admitted under that limit. This is the approach of Sen. Reid. His bill specifies the overall limit of 300,000 and established priorities for admission. The first category is family-sponsored immigration. The level is determined by subtracting from the 300,000 the number of immigrants who are admitted as refugees (up to 50,000) and for employment (up to 40,000). Thus, family-related immigration probably would have an effective limit of about 210,000. This amount would accommodate the current level of spouses and children of U.S. citizens, as the above discussion reveals, but not other family members f citizens or relatives of residents. Persons who qualified for immigration, but could not be accommodated under the annual limit, would be put on a waiting list, as at present.

The overall ceiling approach was also contemplated in the Rockefeller Commission Report. Its suggested ceiling of 400,000 would accommodate 100,000 more than the Reid bill. Nevertheless, reaching reductions to that level would entail major reductions in the component elements of current immigration, including family-related immigration, similar to the Reid bill.

Other approaches to limiting immigration are possible. For example, if the United States should ever decide to adopt a national population policy that encourages parents to forego large families in the interest of a smaller U.S. population, as population control and some environmental organizations urge, then it would be inconsistent with that policy to maintain a fixed-level immigration policy. Rather, at that time it would be appropriate to have an immigration policy that linked admission of new immigrants to the overall size of the U.S. population and the share of the immigrant population in it. Thereby, immigration would decline proportionately with the overall population and stabilize when the population size stabilized.

If the current level of immigration is too high for the long-term best interests of the nation, and there is agreement that it should be reduced to lessen the negative impact of immigration on population growth or jobs competition or increased budgetary costs, then there should be public consideration how best to achieve that objective. As indicated above there are several feasible approaches. Their merits depend to some extent on the magnitude of the reduction below the current immigration level that is sought. The less the reduction, the easier it would be to achieve without a major change in approach. Nevertheless, the above discussion should make clear that a major reduction in immigration is feasible, and it can be accomplished without departing entirely from the core elements of traditional immigration policy.

APPENDIX

The United States first established numerical controls on immigration in 1921. Between the national censuses of 1910 and 1920, U.S. population increased by 13.8 million, about 15 percent, largely because of the arrival of new immigrants numbering over 6.3 million over the same period. Without a numerical limit, immigration exceeded one million newcomers in three of those years. Since 1921, with numerical limits, the level of immigration has exceeded over 600,000 in only nine of the last 70 years, including each of the last seven years. Since then, new immigrants exceeded 800,000 only once, last year.

These data are official INS statistics. They do not include the growing tide of illegal immigrants that swell current overall annual immigration to well over one million. Also not included because they represent a one-time adjustment program are the 2.7 million illegal aliens who were "legalized" pursuant to the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA).

The U.S. population was 105.7 in 1920, compared to over 250 million in 1990. Clearly the demographic character of the country has undergone a profound change over the past seventy years in rural-urban migration, in workforce composition, in living standards, and in educational opportunities.

The U.S. Census Bureau projected in 1989 in its "middle" scenario a peak in U.S. population at about 300 million in fifty years, a subsequent decline. Then, last December, the Census Bureau recognized that the earlier projection was much too low. The new Census Bureau "middle level" projection one that is based on illegal immigration at two hundred thousand per year is that, under currently prevailing conditions, U.S. population growth is on a trajectory in which it will continue to expand indefinitely; in the process, the country is projected to pass the 400 million mark shortly after the middle of the next century.

Finally, the current high-level intake of immigrants, both legal and illegal, has resulted in a rise in the share of the foreign born in the overall population. Earlier in our history, when our population was small, and the continent was being settled in a policy of "manifest destiny," the large influx of immigrants was the intention of the nation's policymakers. The foreign born naturally represented a large share of the population at that time. However, when the westward migration slowed and we restricted immigration, the share of the foreign born declined as new immigrants did not arrive in such great numbers.

By the middle of this century the proportion of the foreign born had stabilized at about five percent of the population. Since then, as immigration has again increased, the foreign-born share of the population has similarly increased to nearly nine percent. If the current high level of immigration and low level of native-born population growth continue, the share of the foreign born in the overall population will continue to rise.

In a population projection designed to demonstrate the impact of immigration on population growth, noted demographer, Dr. Leon Bouvier, has projected alternative scenarios for the U.S. population in the year 2050 if: (A) current trends are continued, and (B) there were no new immigration after the turn of the next century. Without immigration-fed population growth, the country's size would tend to level off at about 311 million at mid-century. With current-level immigration, the population in 2050 is headed for 400 million a difference of over 85 million due to new immigrants and their offspring with no leveling off in sight.

John L. Martin is Research Director of the Center for Immigration Studies.