This Backgrounder provides a detailed picture of the number and socio-economic status of the nation’s immigrant or foreign-born population, both legal and illegal. The data was collected by the Census Bureau in March 2007.

Among the report’s findings:

- The nation’s immigrant population (legal and illegal) reached a record of 37.9 million in 2007.

- Immigrants account for one in eight U.S. residents, the highest level in 80 years. In 1970 it was one in 21; in 1980 it was one in 16; and in 1990 it was one in 13

- Overall, nearly one in three immigrants is an illegal alien. Half of Mexican and Central American immigrants and one-third of South American immigrants are illegal.

- Since 2000, 10.3 million immigrants have arrived — the highest seven-year period of immigration in U.S. history. More than half of post-2000 arrivals (5.6 million) are estimated to be illegal aliens.

- The largest increases in immigrants were in California, Florida, Texas, New Jersey, Illinois, Arizona, Virginia, Maryland, Washington, Georgia, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania.

- Of adult immigrants, 31 percent have not completed high school, compared to 8 percent of natives. Since 2000, immigration increased the number of workers without a high school diploma by 14 percent, and all other workers by 3 percent.

- The share of immigrants and natives who are college graduates is about the same. Immigrants were once much more likely than natives to be college graduates.

- The proportion of immigrant-headed households using at least one major welfare program is 33 percent, compared to 19 percent for native households.

- The poverty rate for immigrants and their U.S.-born children (under 18) is 17 percent, nearly 50 percent higher than the rate for natives and their children.

- 34 percent of immigrants lack health insurance, compared to 13 percent of natives. Immigrants and their U.S.-born children account for 71 percent of the increase in the uninsured since 1989.

- Immigrants make significant progress over time. But even those who have been here for 20 years are more likely to be in poverty, lack insurance, or use welfare than are natives.

- The primary reason for the high rates of immigrant poverty, lack of health insurance, and welfare use is their low education levels, not their legal status or an unwillingness to work.

- Of immigrant households, 82 percent have at least one worker compared to 73 percent of native households.

- There is a worker present in 78 percent of immigrant households using at least one welfare program.

- Immigration accounts for virtually all of the national increase in public school enrollment over the last two decades. In 2007, there were 10.8 million school-age children from immigrant families in the United States.

- Immigrants and natives have similar rates of entrepreneurship — 13 percent of natives and 11 percent of immigrants are self-employed.

- Recent immigration has had no significant impact on the nation’s age structure. Without the 10.3 million post-2000 immigrants, the average age in America would be virtually unchanged at 36.5 years.

Data Source and Methods

Data Source. The data for this Backgrounder comes from the March 2007 Current Population Survey (CPS) collected by the Census Bureau. The March data, which is also called the Annual Social and Economic Supplement, is one of the best sources of information on the foreign-born.1

The foreign-born are defined as persons living in the United States who were not U.S. citizens at birth.2 In this report the terms foreign-born and immigrant are used synonymously. We also use the terms illegal immigrant and illegal alien synonymously. The CPS does not include persons in "group quarters," such as prisons and nursing homes. The March CPS found 37.3 million immigrants in the country. Data collected in 2006 indicates that 613,000 immigrants live in group quarters, for a total foreign-born population of 37.9 million in March 2007.3 The immigrant population in the 2007 CPS included an estimated 11.3 million illegal aliens and roughly one million persons on long-term temporary visas, mainly students and guest workers.4 The CPS is such a valuable source of information because unlike the decennial Census or the American Community Survey, it includes detailed questions on things like welfare use and health insurance coverage.

Recent Trends in Immigration

Figure 1 reports the number of immigrants living in the United States based on the CPS collected in March of each year from 1995 through 2007. Again, the CPS does not include persons in group quarters. The figure shows that between March 1995 and March 2000, the foreign-born population grew by 5.7 million, or about 1.1 million a year.5 The figure also shows that between 2000 and 2007 the immigrant population grew 7.3 million, or 1.04 million a year. These two numbers are the same statistically.

It would appear that the growth in the foreign-born during the economic expansion in the second half of the 1990s was about the same as in the period from 2000 to 2007.6 The seeming large growth from 2006 to 2007 (1.6 million) should be interpreted with caution. While the growth in the last year is statistically significant, one or even two years of data are not necessarily a trend. What Figure 1 does show is that the growth from 1995 to 2007 in the foreign-born has been very high despite changes in the economy over this time period.

Deaths and Out-Migration. When growth in the foreign-born population is discussed, it must be remembered that all children born in the United States to immigrants are by definition natives. The sole reason for the dramatic increase in the foreign-born population is new immigration. Moreover, the increase over time represents a net figure and does not reflect the level of new immigration. New arrivals are offset by deaths and out-migration. Given the age, sex, and other demographic characteristics of the immigrant population, it is likely that there are about 7,500 deaths per million immigrants each year. This number does not change much from year to year, but it does increase gradually over time as the immigrant population grows. As a result, there were roughly 100,000 more deaths a year among immigrants in 2007 than in 1995 because the overall population is 13 million larger. This means that a slower net increase in the immigrant population may not indicate a falling level of new immigration. In addition to deaths, new arrivals also are offset by return migration.

There is an ongoing debate about the size of return migration, but the Census Bureau has estimated that some 280,000 immigrants living here return home each year.7 In total, deaths and return migration equal between 500,000 and 600,000 a year. It should also be remembered that like any survey, there exists sampling variability in the CPS. The margin of error, using a 90-percent confidence interval, for the foreign-born is between 640,000 and 700,000 for data from 1995 to 2001 and between 520,000 and 555,000 for 2002 through 2007 data. (The survey was redesigned in 2002, so the size of the statistical error changed.) Thus, one could say that in 2007 the immigrant population was 37.3 million plus or minus 552,000 and the growth from 2006 to 2007 was statistically significant. However, because of sampling error, even seemingly large year-to-year changes may not be meaningful. When looking for trends, it is much better to compare differences over several years. When we do so, we find that the growth has been dramatic.

Flow of New Immigrants. Another way to examine trends in immigration is to look at responses to the year of arrival question. The CPS asks individuals when they came to America to stay. The 2007 CPS indicates that 10.3 million immigrants (legal and illegal) settled in the United States between January 2000 and March 2007. This implies that slightly less than 1.5 million arrived annually in the United States in the last seven years. Of course, some of the immigrants who arrived in 2000 through 2006 would have died or returned home by 2007, so the actual level of new arrivals is somewhat higher. Some share of the foreign-born population is also missed by the Census Bureau. Prior research indicates that 5.2 percent of immigrants are missed in the CPS.8 So the actual level of new immigration is probably closer to 1.6 million a year. In comparison to the 1990s, the current level seems very similar. The 2000 CPS showed that 8.9 million immigrants (legal and illegal) settled in the country from 1993 to 2000.9 This compares to the 10.3 million who settled in the country from 2000 to 2007. The last seven years match or exceed any seven-year period of immigration in American history.

A Peak After 2000? It is reasonable to wonder how the flow of immigrants has been affected by the downturn in the economy and the 9/11 attacks. There is some evidence that immigration may have dipped after 2001. However, it is very difficult to say because Census Bureau data, including the CPS, are not designed to measure year-to-year changes in the flow of new immigrants. For those interested in a detailed analysis of this issue, please see a CIS study published in December 2005.10 It makes far more sense to compare differences over several years. From a policy perspective, the year of entry question in the 2007 CPS indicates that immigration to the United States continues at record levels. Figure 1 also shows that when we examine 12 consecutive years of the March CPS, the growth in the immigrant population has been remarkably steady, averaging about one million a year for over a decade.

Illegal Immigrants

Illegals in the CPS. It is well established that illegal aliens do respond to government surveys such as the decennial census and the Current Population Survey. While the CPS does not ask the foreign-born if they are legal residents of the United States, the Urban Institute, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), former INS, the Pew Hispanic Center, and the Census Bureau have all used socio-demographic characteristics in the data to estimate the size of the illegal-alien population. We follow this same approach.11 Our preliminary estimates for the March 2007 CPS indicate that there were between 11 and 11.5 million illegal aliens included in the survey, with 11.3 million as our best estimate. It must be remembered that this estimate only includes illegal aliens captured by the March CPS, not those missed by the survey. By design, this estimate is consistent with those prepared by the Census Bureau, DHS, Urban Institute, and Pew Hispanic Center.12 Our estimate for the number of illegals included in the 2000 CPS is 7.3 million. This means that the illegal-alien population in the CPS grew by four million between 2000 and 2007. Figure 1, which compares CPS to CPS, shows a total increase in the immigrant population (both legal and illegal) of 7.3 million from 2000 to 2007. This means that growth in the illegal immigrant population accounted for at least half of the growth in the total immigrant population. We also estimate that 5.6 million of the 10.3 million immigrants in the March 2007 CPS who indicated that they arrived in 2000 or later are illegal aliens.

We estimate that 57 percent of the illegal alien population comes from Mexico, 11 percent is from Central America, 9 percent is from East Asia, 8 percent is from South America, and Europe and the Caribbean account for 4 percent. Of all immigrants from Mexico, 55 percent are illegal; for Central Americans it is 47 percent; and it is 33 percent for South Americans. Again these figures do not adjust for undercount of the legal or illegal populations in the CPS. If we did make this adjustment, it would mean that an even larger share of all immigrants from these regions are illegal because the undercount of illegal immigrants is much larger than the undercount of legal immigrants. Although these estimates are consistent with other research findings, including those produced by the federal government, it should be obvious that there is no definitive means of determining whether a respondent in the survey is an illegal alien with 100 percent certainty.

Illegals as a Share of Growth. The fact that illegals account for at least half of the overall growth in the immigrant population may seem surprising to some, especially since illegal aliens account for 30 percent of the total foreign-born population. There are several reasons for this. First, prior to the mid-1970s, there was little illegal immigration to the United States, thus older immigrants who entered at that time and are still here are almost all legal residents. Because long-time residents are almost entirely legal immigrants, they are older on average than illegal immigrants. Therefore they account for most of the deaths among the foreign-born. Moreover, the United States has conducted broad amnesties for illegal aliens in the past and also each year grants tens of thousands of illegal aliens legal status as part of the normal "legal" immigration process. For example, 2.6 million illegals were given green cards (permanent residency) in the late 1980s and early 1990s as part of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). The immigration service also estimated that during just the 1990s, 1.5 million illegal aliens received green cards, not including IRCA.13 Because there is this constant movement out of illegal status to legal status, the size of the existing legal population is much bigger than the existing illegal population. Finally, it must be remembered that although the number of illegal aliens entering and remaining in the country is now enormous, the level of legal immigration is also very high, adding to a very large legal immigrant population.

Historical Perspective

While immigration has played an important role in American history, the level of immigration and the size of the immigrant population has varied considerably. Figure 2 shows the number of immigrants living in the United States over the course of the last 100 years. The figures 1900 to 2000 are from the decennial census. A question on whether a respondent was foreign-born was not included in the CPS on a regular basis until the mid-1990s, so the decennial census is the only historical data source for the size of the immigrant population prior to that date. In order to make the CPS comparable to decennial census data, it is necessary to include persons in group quarters such as prisons and nursing homes, which are not part of the CPS. Data collected in 2006 indicate that 614,000 immigrants lived in institutions. Adding this to the 37.3 million found in the 2007 CPS creates a total immigrant population 37.9 million in March 2007, assuming no immigrants (legal or illegal) are missed by the survey.14

Figure 2 shows that the 37.9 million immigrants residing in the United States in 2007 is by far the most ever recorded. Even during the great wave of immigration at the turn of the 19th century, the immigrant population was much less than half what it is today. The figure shows that after growing in the early part of this century, the immigrant population stabilized at around 10 or 11 million for about four decades. In the mid-1960s, changes in immigration law and other factors caused the annual level of legal immigration to rise steadily, from about 300,000 a year in the 1960s to nearly a million today. The latest data indicates that this rapid growth has continued into the first decade of the 21st century, adding 6.8 million in the last seven years. This is slightly lower than the 7.2 million growth found in Figure 1, which compared the 2000 CPS to the 2007 CPS . The foreign-born population’s growth rate in every decade since 1970 has been higher than at any other time in history, surpassing the 31 percent increase between 1900 and 1910.

Unlike in the past, the growth in the immigrant population now accounts for a large share of the increase in the size of the U.S. population. Even during the first decade of the last century, the 3.2 million increase in the size of the immigrant population accounted for only 20 percent of the total increase in the U.S. population. In contrast, the 11.3 million increase in the immigrant population from 1990 to 2000 accounted for 35 percent of U.S. population growth in the 1990s. And the 6.8 million increase in the size of the immigrant population in the last seven years equals 34 percent of U.S. population growth between 2000 and 2007.15 It should noted that the 34 percent does not represent the full impact on population growth in the United States because it includes deaths. Net immigration is the way one measures the impact of immigration on population growth, not the net increase in the size of the immigrant population. To measure the full impact of immigration on population growth it also would be necessary to include births to immigrants.

Population growth is measured by taking the number of births minus the number of deaths and then adding net immigration (the difference between people coming and going). The U.S. population is growing by 2.9 million a year according to the Census Bureau.16 The growth in the foreign-born reflects deaths as well as net immigration. Thus, using growth in the foreign-born to measure immigration’s impact on population would be double counting immigrant deaths. For this reason, net immigration is used when estimating the impact of immigration on population growth. As already discussed, annual net immigration is 1.25 million or 1.15 million, depending on how it is calculated. When this is added to the 950,000 births to immigrants each year, the total impact of immigrations is equal about three-fourths of U.S.

population growth.

Immigration now accounts for such a large percentage of population because the fertility of natives was much higher in the early 1900s, during the last great wave of immigration. As a result, the U.S. population grew regardless of immigration. Today, natives have only about two children on average, with the result that without immigration the U.S. population would very slowly move to stabilization.17 Also, in contrast to the past, a higher percentage of today’s immigrants remain in the United States rather than returning home. Because so many immigrants in the early 20th century eventually returned to their home countries, immigration at that time did not add permanently to the overall size of the U.S. population in the way that it does today.18

Immigrants as a Share of the Population. While the number of immigrants and the growth rate of the immigrant population are higher now than at any other time in the last 100 years, Figure 2 shows that the foreign-born percentage of the population was higher in the first few decades of the 1900s, reaching 14.7 percent of the total U.S. population in 1910. As a result of World War I and changes in immigration law in the early 1920s, the level of immigration fell significantly. The 1920 census was the last time the percentage of immigrants was higher than it is today.

In terms of the impact of immigrants on the United States, both the percentage of the population made up of immigrants and the number of immigrants are clearly important. The ability to assimilate and incorporate immigrants is partly dependent on the relative sizes of the native and immigrant populations. On the other hand, absolute numbers also clearly matter. A large number of immigrants can create the critical mass necessary to foster linguistic and cultural isolation. Whether the immigrants in question represent 10 percent or 30 percent of a city or state’s population may not be so important; it’s the raw numbers that may be the most meaningful. And the current numbers are approaching triple what they were in 1910.19 Moreover, absent a change in policy, the number and immigrant-share of the population will continue to increase rapidly for the foreseeable future.

State Numbers

Number of Immigrants by State. Table 1 ranks the states by the size of their immigrant populations. It also shows the number of immigrants who reported arriving in 2000 or later. California clearly has the largest immigrant population; New York, the state with next largest number of immigrants, has fewer than half as many. Table 1 shows how concentrated the immigrant population is: Only a few states represent the majority of the foreign-born population. In 2007, the nearly 10 million immigrants in California account for 27 percent of the nation’s total immigrant population, followed by New York with 11 percent, Florida and Texas with 10 percent each, and New Jersey with 5 percent. These five states account for 61 percent of the nation’s total foreign-born population, but only 32 percent of the native-born population. The table also shows evidence that the immigrant population is becoming more dispersed. Table 1 indicates that although the top-five states account for 61 percent of the total immigrant population, only 54 percent of post-2000 arrivals went to these states.

Share of State That Is Immigrant. Table 1 also shows the share of each state’s population that is foreign-born. While many states with a large number of immigrants are also states where their percentage is high, there are some differences. Because of their relatively small total populations several states with high percentages of immigrants, such as Hawaii and Nevada, rank lower in terms of number of immigrants. It is very likely that the impact of immigration will be significant in these states even though the size of the immigrant population is much smaller than in a state like California.

Growth in the Immigrant Population by State. Table 2 compares the number of immigrants in 1995, 2000, and 2007 for each state.20 It also shows the share of the population that was foreign-born in each of these years. As already discussed, immigrants tend to be concentrated. However, Table 2 also shows that this has become less the case over time. In 1995, the top-five states accounted for 69 percent of the total foreign-born population, in 2000 these same states accounted for 66 percent of the foreign-born and this had dropped to 61 percent by 2007. Or looked at in a different way, these five states accounted for 69 percent of the total immigrant population in 1995, but only 48 percent of the growth in the immigrant population between 1995 and 2007 occurred in these five states. The increasing dispersion of immigrants can be exaggerated; in 2007 the top-10 states of settlement accounted for 75 percent of immigrants, these same states accounted for 80 in 1995. A change to be sure, but not a huge change.

Table 2 also shows different patterns for different states. In New York, for example, the number of immigrants increased 585,000 between 1995 and 2000, but in the seven years after 2000 it grew by 262,000. New Jersey, which is right next to New York, is quite different. The numerical increase in that state was larger between 2000 and 2007 than between 1995 and 2000. The same holds true for Texas. Perhaps the most dramatic increases can be found in Georgia and North Carolina, where the immigrant population increased three and half times between 1995 and 2007. The key point to take from Table 2 is that there is no one pattern that reflects the entire country. The pace and scale varies by state and by time period as well. Table 3 shows the 32 states plus the District of Columbia, where the growth was statistically significant between 2000 and 2007.

Region and Country of Origin

Sending Regions. Table 4 shows the distribution of immigrants by region of the world, with Mexico and Canada broken out separately. Mexico accounts for 31.3 percent of all immigrants, with 11.7 million immigrants living in United States, more than the number of immigrants from any other region of the world. Immigrants from Latin America (Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean) account for the majority of immigrants, with 54.6 percent of the foreign-born coming from these areas. East Asia/Southeast Asia also makes up a significant share of the total, accounting for 17.6 percent of immigrants. This is similar to the combined total for Europe and the Middle East. The importance of the Western Hemisphere, excluding Canada, is even more striking when we look at recent arrivals. Of those who arrived from 2000 to 2007, 58.7 percent are from Latin America.

Top Sending Countries. Table 5 ranks the top-25 immigrant-sending countries by the number of immigrants as of March 2007. Mexico is, of course, the largest sending country, accounting for almost six times as many immigrants as the next largest country, China, which includes Taiwan and Hong Kong. As is clear from Table 4, Latin American and Caribbean countries dominate the list of immigrant-sending countries, accounting for almost half of the top-25 countries. One of the striking things about contemporary immigration is that there has been a significant decline in the diversity of immigrants: Mexico accounts for 31 percent of all immigrants in 2007, up from 28 percent in 2000, 22 percent in 1990, and 16 percent in 1980. The top sending country in 1970 was Italy, which accounted for only 10 percent of the foreign-born.

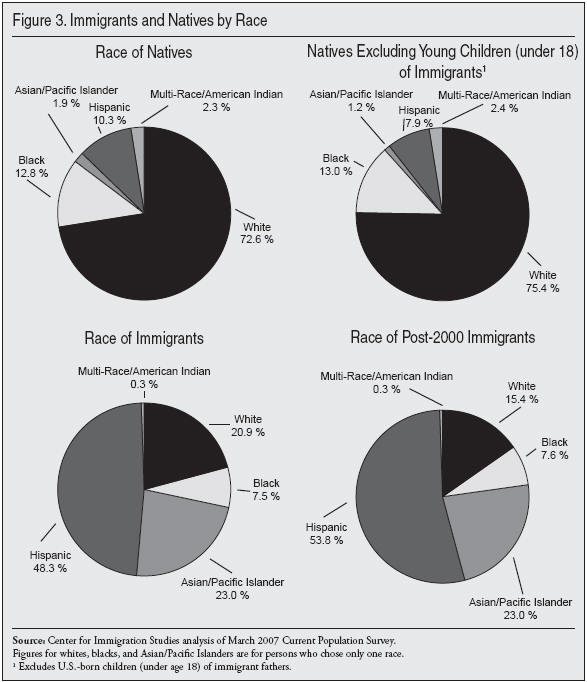

Race and Ethnicity of Immigrants. Figure 3 reports the race of natives and immigrants. Hispanics are treated as a separate category in the figure, so the percentages for whites, blacks, Asians, and others are for non-Hispanics. Race categories are for persons who gave only one race. Multi-racial, non-Hispanic individuals are included with Native-Americans/American Indian. The figure shows that the race of immigrants and natives differs a good deal. A much larger share of immigrants are Hispanic and Asian, and a smaller share is white and black, than is true of the native-born population. Figure 3 also shows this is especially true if the U.S.-born young children of immigrants are excluded.

Selected Characteristics

Educational Attainment. Immigrants now comprise 15.8 percent of the nation’s total workforce 18 years of age and older.21 This is somewhat higher than the 12.6 percent of the total U.S. immigrant population because, in comparison to natives, a slightly higher percentage of immigrants are of working age. The top of Table 6 reports the educational attainment of adult (18 and older) immigrants and natives in the workforce. In 2007, about 29 percent of immigrants 18 and over in the labor force had not graduated from high school. The table also reports the education of adult immigrants in the labor force who arrived from 2000 to 2007. For post-2000 immigrants in the workforce, 35.5 percent had not completed high school. In comparison, slightly less than 8 percent of natives in the workforce lacked a high school education. This difference in the educational attainment of immigrants and natives has enormous implications for the social and economic integration of immigrants into American society. There is no single better predictor of economic success in modern America than one’s education level. As we will see, the fact that so many adult immigrants have little education means that their income, poverty rates, welfare use, and other measures of economic attainment lag far behind natives. The table also shows that a slightly higher share of natives have a bachelor’s degree than immigrants, and the share with a post-graduate degree is almost identical for the two groups.

The large number of immigrants with low levels of education means that immigration policy has dramatically increased the supply of workers with less than a high school degree, while increasing other educational categories more moderately. This is important because it is an indication of which American workers face the most job competition from foreign workers. While immigrants comprise almost 16 percent of the total adult workforce, they comprise more than 40 percent of adults in the labor force who have not completed high school. Figure 4 shows how recently arrived immigrants have increased the supply of different types of workers. It reports the number of immigrants who arrived in 2000 or later divided by the number of natives and pre-2000 immigrants. Thus the figure shows that immigrants since 2000 increased the supply of dropouts in the workforce by 14.4 percent, compared to between 2 to 4 percent in other educational categories. This means that any effect immigration may have on the wages or job opportunities of natives will disproportionately affect less-educated workers, who are already the lowest paid workers.

Immigrant and Native Income. Given the large proportion of immigrants with few years of schooling, it is not surprising that the income figures reported at the bottom of Table 6 show that, as a group, immigrants have lower median incomes than natives.22 The annual median earnings of immigrants who work full-time and year-round is only about 77 percent that of natives. And for the most recent immigrants, median earning are only 61 percent that of natives. Another way to think about immigrant and native earnings is to examine the share of immigrants and natives who have very low incomes. If we look at the 10 percent of full-time, year-round workers with the lowest earnings, we find that 17 percent of immigrants, but only 9 percent of natives fall into the lowest-income decile.

Household Income. Another way to think about the relative position of immigrants compared to natives is to look at household income. The median household income for immigrant-headed households is $43,933, which is 89 percent that of the $49,201 for native households. In addition to having lower incomes, immigrant households are 28 percent larger on average than native households — 3.1 persons versus 2.4 persons. As a result, the per capita household median income of immigrants is only 70 percent that of natives — $14,126 versus $20,247. This is important not only as a measure of their relative socio-economic standing, but also because it has significant fiscal implications. Lower household income means that in general immigrant households are likely to pay somewhat less in taxes than native households. Larger household size means that in general immigrant households will use somewhat more in services than will native households. Since households are the primary basis on which taxes are assessed and benefits distributed in the United States, the lower income and larger size of immigrant households has important fiscal implications.23

Age of Immigrants Table 6 also shows that, in 2007, the average age of an immigrant was 40.5 years compared to 35.9 years for the average native. The fact that immigrants have a higher average age reminds us that although immigrants may arrive relatively young, they age over time like everyone else. The belief that immigration will help fix the problem of an aging society is misplaced. Of course, those who argue that immigration fundamentally changes the age structure generally have in mind new arrivals. Table 6 shows that recently arrived immigrants are somewhat younger than natives — 29.4 years compared to 35.9 years. But the overall impact on the age structure of American society is still small. One simple way to measure the impact of immigration is to calculate the average age in the United States with and without recent immigrants. If all 10.3 million immigrants who arrived in 2000 or later are removed from the data, the average age in the United States would be 36.7 years. Including post-2000 immigrants does lower the average age, but only to 36.4 years. Thus, immigration over the last seven years, which has been numerically the highest in American history, had a very modest impact on the aging of American society.

It could be argued that this meager benefit to the age structure might take more than just seven years of high immigration. In a September 2005 study, the Center for Immigration Studies examined the impact of immigration on the aging of American society as well as the Social Security system. Consistent with other research, we found that immigration has only a small impact on the problem of an aging society now and in the future. While immigrants do tend to arrive relatively young, and have higher fertility rates than natives, immigrants age just like everyone else, and the differences with natives are not large enough to fundamentally alter the nation’s age structure. After looking at the impact of different levels of immigration over the next century, a Census Bureau report stated in 2000 that immigration is a "highly inefficient" means for increasing the percentage of the population who are of working-age in the long run.24 Our detailed look at the full impact of immigration on the nation’s age structure is available online.25

Recently the Center for Immigration Studies completed a series of population projections examining the impact of different levels of immigration on the size and aging of American society. We found that although the current level of immigration will add 105 million to the U.S. population by 2060, it has only a small impact on the share of the population that will be of working age.26 There is a clear consensus among demographers, the people who study human populations, that immigration has only a small impact on the aging of society. A simple analysis of the CPS confirms this conclusion.

Immigrant Progress Over Time. The income figures in Table 6 only consider those in the workforce, and the table groups all immigrants together. Table 7 shows the economic progress of immigrants over time. The first part of the table examines poverty figures.27 Poverty is a good measure because it examines the economic position of those in and out of the workforce. Earnings figures on the other hand are only for those in the workforce. Moreover, poverty controls for the number of people in a family. Table 7 reports the share of immigrants in poverty or who have incomes that place them in or near poverty. In/near poverty is defined as less than 200 percent of the poverty threshold. The 200 percent of poverty threshold is a good benchmark because under that amount people generally do not pay federal income tax and typically begin to be eligible for means-tested programs. Those with income above this amount can be seen as middle class or even upper class, while those with incomes below this amount can be viewed as the low-income population.

Table 7 shows that it takes a very long time for immigrants to close the economic gap with natives. In 2007, the table shows that the poverty rate of immigrants matches that of natives after being here for about 26 to 27 years.28 As for the share in or near poverty, it takes about 28 to 32 years for immigrants to match natives. Because it takes immigrants so long to match the rates of natives, they are much older by that time than is the average native-born American. This is shown in the third column of Table 7. Immigrants who arrived 26 to 27 years ago are 48 years old on average in 2007, 11 years older than is the average native. As a result, immigrants will tend to have lower lifetime earnings and income than natives. A very similar pattern exists when we examine the annual median earnings of full-time, year-round workers. It takes immigrants 28 to 32 years to match the earnings of natives at which time they are in their late 40s, a good deal older than is the average full-time, native-born, year-round worker.

It was once argued that it took 12 to 14 years for immigrants to close the economic gap with natives.29 Table 7 shows this is no longer the case, at least with regard to poverty, near poverty, or earnings. Other measures of socio-economic status also show the great difficulty immigrants have in closing the gap with natives. For example, immigrants are much more likely to lack health insurance than natives, even immigrants who have been in the country for many years. Figure 5 shows the share of immigrant households using welfare, living in or near poverty and without health insurance. Figure 5 shows that welfare use and lack of health insurance is very common, even among well-established immigrants.

It should be noted that there is no way to know whether today’s immigrants will take the same number of years to close the gap with natives, or even if they ever will. But given the education of recently arrived immigrants, it is not reasonable to expect that their income or rates of poverty, un-insurance, and welfare use will converge with natives any time soon. We do know that unskilled immigrants never come close to closing the gap with natives even when they have lived in the United States for many years.30 Coming to live in a new country is never easy, so the slow progress of immigrants could still be viewed as satisfactory depending on one’s point of view. What is clear is that the problem of poverty, low income, welfare use, and lack of health insurance is not something confined to only new arrivals. What is also clear is that immigrants once closed the gap with natives much more quickly. Of course, we could change immigration policy and allow fewer immigrants into the country who have little formal education. If we did that, then immigrants who arrive in the future would almost certainly have incomes that match those of natives from the time they arrive in the United States or soon thereafter.

Occupational Distribution. Table 8 shows the occupational concentration of immigrants and natives. The occupational categories are ranked based on native unemployment rates, which are shown in the first column. The table shows several important facts about U.S. immigration. First, there are millions of native-born Americans employed in occupations that have high concentrations of immigrants. While immigrants certainly are concentrated in particular occupations, it’s simply not correct to say that immigrants only do jobs natives don’t want. The occupational categories of farming/fishing/forestry, construction, building cleaning/maintenance, and food service and preparation currently employ 16.5 million native-born Americans. The second interesting finding in Table 8 is that in the occupations just listed there are nearly 1.8 million unemployed natives. Moreover, native unemployment averages 10 percent in these occupations. Perhaps the labor is not where employers wanted, or there is some other reason businesses find these unemployed natives unacceptable in some way, but on its face Table 8 indicates that there is quite a lot of unutilized labor of this kind in the United States.

It's also worth considering that the correlation between native unemployment rates and the share of an occupation that is comprised of immigrants is .80. The square of a correlation, in this case .63, can be interpreted to mean that the presence of immigrants in an occupation explains 63 percent of the variation in native unemployment rates across occupations. Of course, a correlation does not prove that immigration adversely impacts the employment prospects of natives. It would be a mistake to think that every job taken by an immigrant is a job lost by a native. Many factors impact unemployment rates across occupations. But it would also be a mistake to assume that dramatically increasing the number of workers in these occupations as a result of immigration policy has no impact on the employment prospects of some natives. Given the large number of natives employed in these immigrant-heavy occupations, it would be incorrect to argue that immigrants only do jobs American don’t want.

Self Employment. Table 9 examines the self-employment rates of immigrants and natives. The table shows that immigrants and natives exhibit remarkably similar levels of entrepreneurship. The table shows that 11.3 percent of immigrants and 12.6 percent of natives are self-employed. Turning to self-employment income reported at the bottom of Table 9, we see that the average self-employment income (revenue minus expenses) for both immigrants and natives is virtually identical. While immigrants overall are not more entrepreneurial than natives, immigrants from such countries as Korea, Iran, Italy, and Vietnam are significantly more likely than natives to be self-employed. But, overall entrepreneurship is neither lacking nor a distinguishing characteristic of the nation’s immigrants. If one removed immigrants from the data, the overall rate of self-employment in the United States would be about the same.

Poverty, Welfare, and the Uninsured

Poverty Among Immigrants and Natives. The first column in Table 10 reports the poverty rate for immigrants by country and the second column shows the figures when their U.S.-born children under age 18 are included. Based on the March 2007 CPS, 15.2 percent of immigrants compared to 11.4 percent of natives lived in poverty in 2006.31 (Poverty statistics are based on annual income in the calendar year prior to the survey and reflect family size). The higher incidence of poverty among immigrants as a group has increased the overall size of the population living in poverty. Immigrants accounted for about one in six persons living in poverty. The percentage is larger if the native-born children (under age 18) of immigrants, are counted with their parents. In some reports these children are counted with natives. But it makes more sense to include these children with their immigrant parents because the poverty rate of minor children reflects their parents’ income.32 Table 10 shows that the rate for immigrants and their young U.S.-born children was 16.9 percent compared to the 11.4 percent for natives and their young children. The data by country indicate that there is an enormous variation in poverty rates among immigrants from different countries. For example, the 31.2 percent poverty rate for immigrants from the Dominican Republic and their young U.S.-born children is many times the rates associated with immigrants from countries such as Canada, India, and the Philippines.

Of the 36.5 million people in the United States living in poverty, 3.5 million (9.5 percent) are the U.S.-born children (under 18) of immigrant fathers. The poverty rate for the U.S.-born children of immigrant fathers is 22.6 percent compared to 16 percent for the children of natives. Among persons under age 18 living in poverty, 27.1 percent are either immigrants or the young children of immigrant fathers. Overall, there are 8.4 million immigrants and their young U.S.-born children living in poverty and they account for 23 percent of total poverty population.

In or Near Poverty. In addition to poverty, Table 10 also reports the percentage of immigrants and natives living in or near poverty, with near poverty defined as income less than 200 percent of the poverty threshold. As already discussed, those with incomes under 200 percent of poverty generally do not pay federal income tax and often qualify for means-tested programs. As is the case with poverty, near poverty is much more common among immigrants than it is for natives. Table 10 shows that 40.1 percent of immigrants compared to 28 percent of natives live in or near poverty. If the U.S.-born children of immigrants are included with their immigrant parents, the rate associated with immigrants would be 43.3 percent. Among the young children of immigrants (under 18), 53.6 percent live in or near poverty, in contrast to 35.2 percent of the children of natives. In total, 21.5 million immigrants and their young children live in or near poverty. As a share of persons in or near poverty, immigrants and their young children account for 23.7 percent.

Without Health Insurance. Table 11 reports the percentage of immigrants and natives who were uninsured for all of 2006. (The CPS asks about health insurance in the calendar year prior to the survey.) The table shows that lack of health insurance is a significant problem for immigrants from many different countries. Overall, 33.8 percent of the foreign-born lack insurance compared to 13 percent of natives.33 Immigrants now account for 26.8 percent of all uninsured persons in the United States. This compares to their 12.6 percent of the total population. If the young (under 18) U.S.-born children of immigrants are included with their parents, the share without health insurance is 29.9 percent. The share of children who are uninsured is lower than for their parents mainly because the U.S.-born children of immigrants are eligible for Medicaid, the health insurance program for the poor. Thus the inclusion of the U.S.-born children pulls down the rate for immigrants slightly. In total, there are 14.9 million uninsured immigrants and their young U.S.-born children in the country, accounting for 31.7 percent of all persons without health insurance. This is roughly double their share of the total population, which is 16.7 percent. Of young children (under 18) without health insurance, 38.1 percent (3.3 million) are immigrants or the young U.S.-born children of an immigrant father. Recently there has been a debate over extending SCHIP, which is a form of Medicaid, to more young children with incomes below 200 percent of poverty. Currently, 43 percent of low-income uninsured children (under 18) are immigrants or the U.S.-born children of immigrant fathers. While not generally acknowledged, immigration is at the center of the current SCHIP debate.

The low rate of insurance coverage associated with immigrants is primarily explained by their much lower levels of education. Because of the limited value of their labor in an economy that increasingly demands educated workers, many immigrants hold jobs that do not offer health insurance, and their low incomes make it very difficult for them to purchase insurance on their own. A larger uninsured population cannot help but strain the resources of those who provide services to the uninsured already here. Moreover, Americans with insurance have to pay higher premiums as healthcare providers pass along some of the costs of treating the uninsured to paying customers. Taxpayers are also affected as federal, state, and local governments struggle to provide care to the growing ranks of the uninsured. There can be no doubt that, by dramatically increasing the size of the uninsured population, our immigration policy has wide-ranging effects on the nation’s entire healthcare system.

One study found that after controlling for such factors as education, age, and race, uninsured immigrants impose somewhat lower costs than uninsured natives. However, when the authors simply compared uninsured immigrants to uninsured natives the cost differences were not statistically significant. In other words, when using the actual traits that immigrants have, the costs that uninsured immigrants create were the same as uninsured natives.34 Of course, even if there was a difference in the costs uninsured immigrants create when compared to uninsured native, it would have to be enormous to offset the fact that immigrants are two-and one-half times more likely to be uninsured than native-born Americans.

Immigration Accounts for Growth in Uninsured. According to the Census Bureau, since 1989 the population without health insurance has grown by 14.62 million and stood at 47 million in 2006. Much of this growth has been driven by immigration. To understand the impact of immigration, we can remove from the CPS immigrants who lack health insurance and arrived after 1989. In the March 2007 CPS there were 9.21 million immigrants who arrived in 1990 or later who did not have health insurance. This is equal to 62.9 percent of the growth in the uninsured population. Moreover, there were 1.12 million children born to post-1990 immigrants who also lacked insurance, meaning that new immigrants and their U.S.-born children accounted for 71 percent of the growth in the uninsured population.

Uninsured or on Medicaid. The 2007 CPS shows that 17.7 percent of immigrants and their U.S.-born children under 18 are on Medicaid, compared to 11.9 percent of natives and their children.35 Of immigrants and their young children (under 18), 47.4 percent either have no insurance or have it provided to them through the Medicaid system compared to 25 percent for natives and their children.

Welfare Use. As the Census Bureau does in its publications, we report welfare use based on whether the head of the household is immigrant or native.36 With regard to immigrant households, this means we are mainly reporting welfare use for immigrants and their U.S.-born children who live with them and comparing them to natives and their children. Table 12 shows the percentage of immigrant- and native-headed households in which at least one member of the household uses one or more welfare programs. Cash assistance includes Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), state administered general assistance, and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which is for low-income elderly and disabled persons. Food assistance includes food stamps, free school lunch, and the Women Infants and Children nutrition program (WIC). Housing assistance includes subsidized and government-owned housing. Medicaid, the health insurance program for those with low incomes, is also included.

The left side of Table 12 shows the share of all immigrant and native households using different types of welfare. The table indicates that even after the 1996 welfare reforms, which curtailed eligibility for some immigrants, immigrant households’ use of the welfare system remains higher than that of natives for most programs and most entering cohorts. Use of cash tends to be quite similar for immigrant and native households. Thus if by "welfare" one only means cash assistance programs, then immigrant use is roughly the same as that of natives. Of course, there is the question of whether native use of welfare is the proper yardstick by which to measure immigrants. Some may reasonably argue that because immigration is supposed to benefit the United States, our admission criteria should, with the exception of refugees, select only those immigrants who are self-sufficient. Table 12 shows that welfare use, even of cash programs, is not at or near zero.

Table 12 shows that use of food assistance is significantly higher for immigrant households than native households — 19.4 percent versus 10.4 percent. The same is true for Medicaid: 24.4 percent of immigrant households have one or more persons using the program compared to 14.7 percent of native households. From the point of view of taxpayers, immigrant use of Medicaid is the most problematic because that program costs more than the combined total for the other programs listed.

As was the case with lower income and higher poverty rates, the higher welfare use rates by immigrant households are at least partly explained by the large proportion of immigrants with few years of schooling. Less-educated people tend to have lower incomes. Therefore, it is not surprising that immigrant use of the welfare system is significantly higher than that of natives.

While immigrants’ use of some welfare programs is higher than it is for natives, Table 12 shows that most households, immigrant or native, do not use the welfare system. On the other hand, even though most people in the country do not use the welfare system, the programs listed in Table 12 cost the government some $600 billion annually.

Use of the EITC and ACTC. In addition to welfare programs, Table 12 reports the share of households in which at least one worker is eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC).37 Workers receiving the EITC generally pay no federal income tax and instead receive cash assistance from the government based on their earnings and family size. The ACTC works in the same fashion, except that to receive it, one must have at least one dependent child.

The IRS will process the EITC and ACTC automatically for persons who file a return and qualify. Even illegal aliens sometimes receive the EITC and ACTC. This is especially true of the ACTC because the IRS has determined that illegals are allowed to receive it, even if they do not have a valid Social Security number. To receive the EITC one must have a valid Social Security number. With an annual cost of over $35 billion for the EITC and $14 billion for the ACTC, the two programs constitute the nation’s largest means-tested cash assistance program for low-income workers.

Table 12 shows 17.8 percent of native-headed households have enough dependents and low enough income to qualify for the EITC and 10.9 percent have low enough incomes to receive the ACTC. This compares to 31.1 and 22.5 percent of immigrant households. For both programs, about twice the share of immigrant households are eligible as are native households. The figures for the EITC and ACTC probably overstate receipt of the programs for both immigrants and natives because they are imputed by the Census Bureau based on income and family size. This is in contrast to the welfare programs listed, which are based on self-reporting by survey respondents.38

Given the education level of so many immigrants, it is not surprising that a large share work but that their incomes are low enough to qualify for the EITC. It important to understand the high rate of EITC and ACTC eligibility does not reflect a lack of work on the part of immigrants. In fact, one must work to be eligible for them. Use of the EITC and ACTC mainly reflects a lack of education and resulting low incomes, coupled with the presence of dependents.

Welfare Use by Country. While on the whole immigrant households have higher welfare use rates, this is not true for immigrants from all countries. Table 13 shows that immigrants from some countries have lower welfare use rates than natives. From the list of countries in Table 13, it is also clear that refugee-sending countries, such as the former USSR and Cuba, tend to use the welfare system a good deal. On the other hand, Mexican and Dominican households have welfare use rates that are much higher than natives — even higher than the former USSR and Cuba — and virtually none of these immigrants are refugees. In fact, if one excludes the primary refugee-sending countries, as shown in the bottom portion of Table 13, the share of immigrant households using a welfare program remains virtually unchanged at 32.6 percent.39 Refugees are simply not a large enough share of the foreign-born, nor are their rates high enough, to explain the level of welfare use by immigrant households.

Welfare Use Among Working Households. The bottom of Table 13 makes a number of different comparison between immigrant and native households. One of the most important is to compare welfare use among households with at least one worker. The table shows that 31.1 percent of immigrant households with at least one working person still use the welfare system. This compares to 16.4 percent of native households with at least one worker. In particular, food assistance programs and Medicaid are often given to working families. This is an important point to understand. Most immigrant households have at least one worker. We estimate that 82 percent of immigrant households have at least one worker compared to 73 percent of native households. But this in no way means they will not use the welfare system because that system is increasingly designed to provide assistance to low-income workers with children, a description of immigrant families given their education levels and relatively high fertility. In fact, a worker is present in 78 percent of immigrant households using at least one welfare program. For native households it’s 62 percent. Most immigrants work, but this does not make them self-sufficient.

Educational Attainment

Education Level of Immigrants. The statistics reviewed thus far indicate that a larger share of immigrants than natives have low incomes, lack health insurance, and access means-tested programs. As already mentioned, one of the primary reasons for this situation is that many immigrants have relatively few years of schooling. Table 14 reports the share of immigrants and natives ages 25 to 64 who have less than a high school education and the share who have at least a bachelor’s degree by country. (The overall figures do not exactly match those in Table 6 because in that table the percentages are for only those in the labor force.) The big difference between the education level of the two groups is found at the bottom end of the education distribution. In 2005, 30.6 percent of immigrants ages 25 to 64 lacked a high school diploma, compared to less than 8.4 percent of natives.

At the top end, natives now have a slight advantage in terms of having at least a bachelor’s degree. Historically, immigrants enjoyed a significant advantage in terms of having a college education. In 1970, for example, 18 percent of immigrants (25 to 64) had at least a college degree compared to 12 percent of natives.40 But as Table 14 shows this is no longer the case, with 29.1 percent of immigrants and 31.1 percent of natives having at least a college degree.41 Because education is now so important to economic success, the large share of immigrants with relatively little education has enormous implications for their economic and social integration into American society. Table 14 shows that there is great variation in the education level of immigrants by country. As we have seen, there is also great variation in the poverty, welfare use, and health insurance coverage rates by country. Comparing the education levels found in Table 14 with prior tables shows that, in general, countries with the lowest levels of education are also the ones with highest rates of poverty, welfare use, and lack of health insurance.

Importance of Education. To see just how important education is to economic success, Table 15 reports income, welfare use, poverty, and health insurance rates for immigrants and natives by education level. Turning first to annual earnings of year-round, full-time workers, the median earnings of these immigrant workers is 77 percent that of natives. But Table 15 shows that the median annual earnings of immigrants without a high school degree who work full-time, year-round is 87 percent that of natives with the same education. For those with only a high school degree and no additional schooling, immigrants earn 84 percent of what natives earn. Immigrants with some college earn 94 percent of what natives with the same education earn, and those with at least a college degree earn 98 percent of what natives earn. Overall, the differences by education are much less than is the overall difference. This means that a large share of the difference in the median earnings of natives and immigrants is explained by the low educational attainment of many immigrants. Table 15 also shows that for welfare use, poverty, and health insurance rates, immigrants tend to do somewhat worse than natives with the same education. But more importantly, the table indicates that how well immigrants do is heavily dependent on their education level. This is consistent both with common sense and a very large body of research.

The current immigration system allows most legal immigrants into the country through family re-unification channels primarily based on whether they have a relative here. This fact, coupled with widespread tolerance of illegal immigration, means the foreign-born population as a whole is much less educated than the native-born population. Given the nature of the modern American economy and the existence of a well-developed welfare state, it seems unavoidable that less-educated immigrants will tend to have lower incomes, make heavier use of means-tested programs, and be more likely to lack health insurance than natives.

Characteristics by State

In this section we examine the demographic characteristics of immigrants by state. Since the sample is much smaller than for the nation as the whole, the results should be interpreted with caution, especially for the smaller states.

Household Characteristics by State. Table 16 reports the median income and average household size of immigrant and native households for top immigrant-receiving states.42 In most, but not all, states immigrant households have significantly lower median incomes than do native households. But perhaps most importantly, immigrant households are significantly larger on average. As a result, the per-person median household income is much less for immigrant households than native households in every state. For example, immigrant households in Illinois have a median income that roughly matches those of native households, but the average immigrant household in that state is one-third larger. Thus, as the last column in Table 16 shows, the per-person median income of native households in the state is 33 percent higher than that of immigrant households. Lower household income coupled with larger household size means that the typical immigrant household is likely to pay somewhat less in taxes and use somewhat more in services than the typical native household because households are the primary basis on which taxes are assessed and benefits are distributed.

Of course, payroll tax payments reflect income and number of dependents, and the net fiscal effects also reflect use of social services. As we have seen, immigrant households do tend to use more in welfare and other means-tested programs than native households. But, reflecting their age structure, immigrant households use relatively less in Social Security and Medicare, the health insurance for those over 65. While both welfare and retirement programs are very costly, there is a very important difference between the two sets of programs. Use of Medicare and Social Security is nearly universal among those who live to old age, including immigrants. Lack of health insurance or welfare use is not universal. Put a different way, all people grow old, but not all people use the welfare system. As a policy matter, there is no way to select immigrants who will not grow old, but by selecting more educated immigrants we could significantly reduce use of means-tested programs by immigrants in the future if we wish to do so.

School-Age Population. In the last few years, a good deal of attention has been focused on the dramatic increase in enrollment experienced by many school districts across the country. All observers agree that this growth has strained the resources of many school districts. While it has been suggested that this increase is the result of the children of baby boomers reaching school age, the so called "baby boom echo," it is clear from the CPS that immigration policy accounts for the dramatic increase in school enrollment. Table 17 shows that there are 10.8 million school-age children of immigrants (ages 5 to 17) in the United States, accounting for 20.2 percent of the total school-age population.43 While fewer than one-fourth (2.7 million) of these children are immigrants themselves, the use of public education by the U.S.-born children of immigrants is a direct consequence of their parents having been allowed into the country. The children of immigrants account for such a large percentage of the school-age population because a higher proportion of immigrant women are in their childbearing years, and immigrants tend to have somewhat larger families than natives. In addition, the effect of immigration on public schools will be even larger in the coming years because 22.6 percent of children approaching school age have immigrant mothers.

Table 17 also shows that immigration has significantly increased the school-age population in all of the top immigrant-receiving states. Of course, a dramatic increase in enrollment may not create a problem for public education if tax revenue increases proportionately. But as we have seen, immigrants themselves and immigrant households generally have lower incomes than natives, so their tax contributions are unlikely to entirely offset the costs they impose on schools. This is especially true because of the higher costs associated with teaching children whose first language is not English.

Citizenship and Educational Attainment by State. Table 18 reports the citizenship, education level, and poverty rates for immigrants. The table shows citizenship rates vary a great deal by state, with Arizona and North Carolina having the lowest rate and New York and Massachusetts having the highest. The table shows that in every state the share of adult immigrants without a high school education is significantly higher than that of natives. The largest gap is found in western states such as California, Arizona, and Colorado, where four to eight times as many immigrants as natives are high school dropouts. This huge gap has enormous implications for the social and economic integration of immigrants because there is no better predictor of one’s economic and social status in modern America than education.

(Click here to see a larger version of Table 18)

Poverty and Near Poverty by State. The two columns after citizenship and educational attainment in Table 18 report the percentage and number of immigrants and their U.S.-born children (under age 18) who live in poverty compared to natives and their children. While the foreign-born tend to have higher poverty rates in the top-receiving states, in Massachusetts, Illinois, Virginia, Maryland, and Georgia the difference with natives is not that large. In contrast, immigrants and their children tend to have much higher rates of poverty in North Carolina, Texas, Colorado, and Arizona. Turning to the share in or near poverty we see a somewhat different pattern. (Near poverty is defined as having an income below 200 percent of the poverty threshold.) With the exception of Maryland, immigrants and their young children have much higher rates of poverty/near poverty than natives in every major immigrant state. As already discussed, those with incomes below this amount usually do not pay income taxes, and they typically become eligible for means-tested programs. As a share of all persons in or near poverty, immigrants and their children account for more than one-half of the poor and near poor in California and roughly one-third in New York, New Jersey, Florida, Texas, and Arizona.

Welfare Use by State. Table 19 shows the percentage of immigrant- and native-headed households using at least one welfare program. (Programs included are TANF, SSI, general assistance, food stamps, WIC, free school lunch, public/rent-subsidized housing, and Medicaid.) Nationally, 32.7 percent of immigrant households use a welfare program compared to 19.4 percent of natives. As we saw in Table 12, the biggest difference in program use is for Medicaid and food assistance programs. For state governments, Medicaid is a particular concern because between one-third to one-half of the program’s costs are typically borne by state taxpayers. The biggest difference in overall welfare use is found in Texas, California, Arizona, Massachusetts, and Georgia. As a result of their higher use rates, immigrant households account for a very significant percentage of the those using the welfare system. In California, almost half of households using a welfare program are headed by immigrants, and in New York, Florida, Texas, New Jersey, and Arizona immigrant households account for between a quarter and one-third of households using the welfare system.

Health Insurance Coverage. Table 20 shows the share of immigrants and their children without health insurance by state. In the nation as a whole, 30 percent of immigrants and their children (under 18) are uninsured, compared to 13 percent of natives and their children. The difference between immigrant and native insurance coverage rates can only be described as enormous in many states. In states such as Colorado, Arizona, North Carolina, and Virginia the rate of uninsurance among immigrants and their children is triple that of natives. In almost every other state shown in Table 20, the uninsurance rate is double or nearly double that of natives.

The impact of immigration on the healthcare system as a whole can also be seen when we consider the share of immigrants and their minor children who are either uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid shown in the last columns of Table 20. The 2007 CPS shows that 17.4 percent of immigrants and their children are on Medicaid, compared to 12 percent of natives and their children. When we combine the share on Medicaid with the share without health insurance, we find that in the nation as a whole 47.4 percent of immigrants and their children (under 18) are either uninsured or on Medicaid. In comparison, 25 percent of natives and their young children are uninsured or on Medicaid. In Arizona and Texas, more than 60 percent of immigrants and their young children are uninsured or on Medicaid. In Colorado, North Carolina, Georgia, and California half or more of immigrants and their children are uninsured or on Medicaid. The impact of immigration on the healthcare system in these states and the nation is clearly enormous.

Size of the Poverty, Uninsured, and School-Age Populations. Figure 6 shows the percentage of the nation’s total population comprised of immigrants alone and immigrants plus their U.S.-born children under age 18.44 The figure also shows the share of the poverty population, uninsured population, and school-age population that is either immigrants or their children. Overall, immigrants and their children are 16.7 percent of the total population, but comprise 23 percent of the poverty population, 31.7 percent of the uninsured, and 20.2 percent of the school-age population. Figure 6 makes clear that an appreciation of immigration’s impact is necessary to understand poverty, health insurance, or the situation of the nation’s public schools.

Figure 7 shows some of the same statistics by each state for immigrants and their U.S.-born children under age 18.45 As a share of all persons in poverty, immigrants and their children account for more than one-half of the poor in California, and roughly one-third in New York, Colorado, Texas, Florida, and Arizona. The impact of immigration on the overall size of the uninsured population is even larger. In California immigrants and their U.S.-born children under 18 are 57.5 percent of the uninsured, and they are almost half of the uninsured in New Jersey. They also represent a third or more of the uninsured in Arizona, Texas, Florida, Virginia, Maryland, and Colorado.

(Click here to see a larger version of Figure 7)

Illegal Immigration

Illegal Population Overall. So far we have examined the size, growth, and characteristics of the nation’s total foreign-born population. As discussed in the methods section of this report, the foreign-born population in the CPS includes both legal and illegal immigrants. We estimate that of the 37.3 million immigrants, 11.3 million are illegal aliens. It must also be remembered that these figures are only for those in the CPS, not those missed by the survey. Our estimates indicate that illegal aliens comprise 3.8 percent of the nation’s total population and 30.4 percent of the total immigrant population. Estimates prepared by other researchers often adjust for undercount in Census Bureau data. While there is debate about the number missed, most research indicates that roughly 10 percent of the illegals are not counted in the CPS.46 Thus, the "true" size of the illegal population could be 12.4 million (11.3 million plus 1.1 million for undercount). If the undercount is larger, then the total illegal alien population is larger.

One of the most important characteristics of illegal immigrants is the very large share with little formal education. We estimate that 57 percent of adult illegal immigrants (25 to 64 years of age) have not completed high school, 24 percent have only a high school degree, and only 19 percent have education beyond high school. As already discussed, this is critically important because education is so important to socio-economic status in the modern American economy.

Illegals by State. Below we examine the demographic characteristics of illegal aliens by state. Since the sample size is much smaller for individual states than for the nation as a whole, the results should be interpreted with caution, especially for the smaller states. In addition to issues associated with sample size, it also should be remembered that the identification of illegals in the survey contains some error. Table 21 reports our best estimates for the number of illegals by state in the CPS. (It should be noted that even if the undercount is 10 percent nationally, as many researchers think, this may not be uniform across states.) Table 21 shows that California has by far the largest illegal population, followed by Texas, Florida, Arizona, and New York. However, with the exception of Texas and Arizona, these states do not rank at the top in terms of the illegal share of the total foreign-born. In Arizona, North Carolina, Georgia, and Texas, illegals account for half or more of the total immigrant population.

Employment of Illegal Immigrants. Table 21 also shows the number of illegals holding a job in each state. In total, nearly 6.9 million illegals currently work in the United States out of a total illegal-alien population in the CPS for 11.3 million.47 The table also shows the number of less-educated natives ages 18 to 64 years of age not holding a job. This includes those who are unemployed, which means they are looking for work, as well as those who are not working and say they are not looking for work. Less-educated is defined as either having not completed high school or having a high school education, but no additional schooling. Native-born teenagers (15 to 17) not holding a job are also shown.

It is often suggested that there are simply no Americans to fill jobs taken by illegals. To examine this question it is necessary to look at the number of teenagers and natives with little education who are not working. This makes sense because illegal aliens are overwhelmingly less-educated. Therefore, it is less-educated natives who might face job competition from illegals. Table 21 indicates that there are 22.3 million less-educated native-born adults (18 to 64) and 10.1 million native-born teenagers (15 to 17) not holding a job. Roughly half of these adults and one-third of the teenagers live in the top states of illegal-immigrant settlement listed in Table 21. In addition to the millions of less-educated natives living in states with large illegal populations, the millions of adults living in low-immigration states could represent a source of labor for employers in high-illegal-immigrant states if given an incentive to move, such as higher pay. Table 21 indicates that there would seem to be a very large pool of potential workers who might be employed if there were fewer illegal aliens in the country. For a variety of reasons many people not working do not wish to work and no incentive could induce them to hold a job. But if only one in four less-educated adults natives and one in seven native-born teenagers currently not working took a job, it would equal the entire number of illegal aliens currently holding jobs.48 We do know that the share of less-educated adults and teenagers working used to be higher, but it has declined significantly in recent years.49

Illegals’ Income by State. Table 22 shows the average income and size for households headed by illegal immigrants. We use average income and not median income because at the household level it is not possible to calculate median income figures due to sample size in most states.50 Not surprisingly, Table 22 shows that the mean income of illegal households is much smaller than the mean income of native households. At the same time these households are much larger on average than native households. In most states, illegals have household incomes that are between 25 and 50 percent less than native households. At the same time, illegal alien households are at least 40 percent larger than native households in most states. As already discussed, lower household income coupled with larger household size means that, on average, illegal-alien households will pay less in taxes and use more in services than native households because households are the primary basis on which taxes are assessed and benefits distributed in the United States. Even assuming that illegals pay all the taxes they are supposed to, it is difficult, given their average household income and size, for illegals not to create a significant fiscal drain.

But again, it must be pointed out that this situation arises because of the education level of illegals and not because they do not work. The vast majority of working-age illegals work. In fact, we estimate that 92 percent of illegal-alien households have at least one person working. This compares to 73 percent of native-headed households. But because of their education levels, a very large share of illegal households have low incomes, and very low per capita household income.

Illegals and the School-Age Population. One advantage of not adjusting for undercount is that it is possible to see what share of those in poverty, without health insurance, or in public schools are illegal immigrants in the CPS. If we had adjusted upward for those illegal missed in the CPS, then figures would no longer match the survey, which is the primary source for government statistics on things like poverty or the uninsured. Not adjusting makes it possible to estimate what share of the poverty or uninsured populations, as shown in official government publications, are illegal immigrants.51 Table 23 reports the estimated number and share of the school-age population in the United States that is comprised of illegal immigrants. Overall illegals account for 1.5 million school-age children or 2.8 percent of all 5 to 17 year olds. This is smaller than the 3.8 percent illegals represent of the nation’s total population because immigrants, including illegal aliens, generally come to the United States after age 17, so there are relatively fewer illegals under age 18. Table 23 also shows that school-age illegal aliens plus the U.S.-born children of illegal aliens comprise 6.2 percent (3.3 million) of the total school-age population.52 Since per-student expenditure in the United States is very roughly $10,000 a year, it is likely that $15 billion annually goes to educate illegal aliens in public schools. The total cost for educating illegal aliens and the U.S.-born children of illegal aliens likely comes to over $30 billion a year. In states such as New Jersey, Texas, Arizona, Florida, and California illegal immigrants comprise significantly more than the national average. Thus the impact of illegal immigration in some parts of the country is much larger.