Related Publications: Panel Transcript, Panel Video

Download a pdf of "Cheap Labor as Cultural Exchange"

The Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) report, “Cheap Labor as Cultural Exchange: The $100 Million Work Travel Industry”, is based on five months of reporting by CIS senior research fellow and Pulitzer Prize-winning former journalist Jerry Kammer.

The series tells the story of the State Department’s troubled Summer Work Travel (SWT) program and its rapid growth over the past 15 years into a $100 million international industry that has spread around the globe. SWT is emblematic of a larger problem with the nation’s immigration system, where new programs are created and allowed to expand significantly without giving careful consideration to their impact on the labor market or the larger American society.

2011 was particularly turbulent for SWT. When the State Department issued new regulations in the spring, it acknowledged that some sponsors were neglecting their duties and that the existing regulations “do not sufficiently protect national security interests, the Department’s reputation, and the health, safety and welfare of Summer Work Travel program participants.” In short, the program had been infected by many abuses, leaving some participants defrauded and allowing others to be recruited by organized crime or strip club owners.

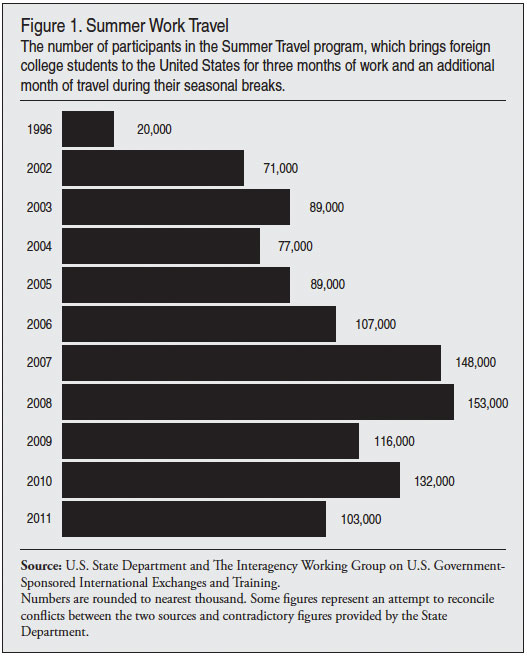

In the summer of 2011, Stanley Colvin, the State Department official who long directed SWT and other exchange programs, was quietly replaced. Then the Hershey protest brought global notoriety to the program. In October, according to Rick Ruth, who replaced Colvin, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton "directed the State Department to conduct a thorough and rigorous review of the Summer Work Travel program and make recommendations" aimed at ensuring that the program "fulfills its original purpose as a cultural program for foreign college and university students." In early November, Ruth announced that the number of SWT participants for 2012 would be frozen at its 2011 level of about 103,000. That move, he said in December, would facilitate a review aimed at "determining how to best move forward, via program reforms and new administrative procedures."

Kammer, a former investigative reporter, tells the story of the State Department’s inability to establish proper management of SWT despite years of criticism by the Government Accountability Office and State's own Inspector General.

Part One: The Globalization of the Summer Job. The story of SWT’s role in international diplomacy and of the intense, sophisticated, and lucrative recruitment both of the students whose fees fuel the industry and the employers who provide the jobs.

Part Two: Young Americans "Don't Know How the System Works". The story of young Americans displaced by SWT, which uses international job fairs to line up summer workers months in advance. A second story tells of the culture clash at Hershey, where the legend of a benevolent chocolate baron met the harsh reality of SWT.

Part Three: SWT in Alaska: Fish Sliming as Cultural Exchange. The story of SWT in Alaska, where some 2,000 "cultural exchange" workers take jobs that used to be magnets for American college students, including 1969 Wellesley graduate Hillary Rodham, now overseeing SWT as Secretary of State.

Part Four: "A Cavalier Attitude": The State Department's Legacy of SWT Failure. The story of the State Department’s long history of mismanagement of SWT, including its indifference to its effects on American workers. Included is an interview with Rick Ruth, the State Department’s new man in charge of SWT.

Epilogue: An open letter to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. CIS calls on Secretary Clinton, whose department oversees the SWT program, to reform it so today’s young Americans can enjoy the same summer work experiences as she did many years ago.

The Globalization of the Summer Job

In the summer of 1969, after graduating from Wellesley College and before entering Yale Law School, a young woman from Illinois named Hillary Rodham scooped the innards from salmon at a cold, wet processing plant in Valdez, Alaska. “I slimed fish,” she recalled during a visit to Anchorage as First Lady in 1994. “I was handed a spoon, some hip boots and a raincoat, and I think it was the best preparation for living in Washington.” Her husband, President Bill Clinton, quipped that, “in Washington you have to trade the spoon in for a shovel.”1

For decades, summer jobs in Alaska have beckoned to American college students eager to earn good money and revel in the state’s natural wonders. But in 2011 about 2,000 of these jobs – at fish processing plants, national parks, and other locations – were filled by young foreigners who come to the United States under a “cultural exchange” program administered by the State Department, which is directed by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton.

They are participants in the Summer Work Travel program (SWT). Every year SWT provides J-1 visas to more than 100,000 college students from around the world, allowing them to work for three months and take an additional month to travel. Because they pay an average of about $1,100 in fees to the private organizations that sponsor their participation in the program, the program generates well over $100 million in annual revenues for those organizations. They pay many millions more in visa fees to the State Department and in travel expenses to and from the U.S.2

The J-1 students, as they are sometimes known, can be found at national parks and beach resorts; amusement parks and neighborhood swimming pools; seafood processing plants and farms; upscale restaurants and fast food franchises; convenience stores, toy stores, and candy shops; roadside vegetable stands; factories, warehouses and moving companies. All in the name of cultural exchange.

“The sky is really the limit,” says the website of a Singapore travel agency that promotes the program through its affiliation with U.S. organizations designated by the State Department to sponsor SWT participants. The website declares that “there are thousands of cities and towns throughout America that can offer you a totally unique Work and Travel USA experience.”3

There are hundreds of such agencies that promote SWT around the world. Their websites buzz with too-good-to-be true astonishment at the program’s benefits for employers and workers alike.

“Sounds like a scam?” a Russian agency asks on its website, which notes that employers of SWT participants are exempt from Social Security, Medicare, and federal unemployment taxes. Then it answers the question: “It’s not. This is Work and Travel USA program, designed by the U.S. Dept. of state to promote intercultural friendship.”4

Critics claim that the State Department office responsible for administering the program has provided such lax regulation and permissive oversight that it has spun out of control and – in some cases – into the hands of abusive employers, unscrupulous sponsors, and predatory third-party agencies overseas.

The list of specific criticisms is long, including claims that the SWT program:

- has become a cheap-labor program under the guise of cultural exchange;

- has monetized a foreign policy initiative, creating a multi-million dollar SWT industry that generates enormous profits under the mantle of public diplomacy and presses for continual expansion around globe;

- is so dominated by the State Department’s concerns about international relations that it has become blind to the negative effects at home;

- displaces young Americans from the workplace at a time of record levels of youth unemployment;

- provides incentives for employers to bypass American workers by exempting SWT employers from taxes that apply to employment of Americans. Employers also don’t have to worry about providing health insurance, since SWT students are required to buy it for themselves;

- puts downward pressure on wages because it gives employers access to workers from poor countries who are eager to come to the United States, not just to earn money but also to travel within the country and burnish their resumes by learning English;

- depends upon young foreigners who must spend several thousand dollars in fees, travel costs, and health insurance. As a result, many are virtually indentured to U.S. employers and are therefore unable to challenge low pay and poor working and housing conditions;

- is not truly an exchange program because it lacks reciprocity since a negligible number of young Americans find overseas employment through the SWT sponsoring agencies;

- has become a gateway for illegal immigration by SWT participants who overstay their visas; and

- has been exploited by criminals. For instance, in 2009, a State Department cable noted an ongoing investigation of “a Eurasian Organized Crime group operating in Colorado and Nevada that is suspected of using 28 Summer Work and Travel exchange program students … to participate in financial fraud schemes.”5

* * *

In the spring of 2011, State acknowledged that the Department of Homeland Security “has reported an increase in incidents involving criminal conduct (e.g. money laundering, identity theft, prostitution)” among SWT participants.6 That acknowledgement came as State issued new regulations intended to curb abuse of the program and require sponsors to fulfill their duty to monitor and advise their young customers.

State, which is supposed to oversee and regulate the sponsors, admitted that some of them had been so detached from their responsibilities that they became “mere purveyors of J-1 visas, leaving the actual program administration to third parties.”7

In the fall of 2011, as criticism mounted and Ann Stock, Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs, made a series of personnel moves, she quietly pushed Stanley S. Colvin out of his job as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Private Sector Exchange. Colvin, who is challenging the move as a violation of his rights, has been assigned to the job of “strategic adviser” to the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.

Colvin had been involved in managing the program since the 1990s, when he was assistant general counsel at the United States Information Agency. The USIA administered SWT until 1999, when it was absorbed into the State Department.

In November of 2011, State announced the first-ever numerical restriction on the size of the program, freezing it at the 2011 level in response to what it called “unacceptably high” numbers of complaints about program abuses.8

That move was a sharp departure from State’s previous policy of promoting the growth of SWT – and other exchange programs – around the world.

For years, State has spread the news of exchanges with a missionary intensity. Dina Habib Powell, a State Department official in the administration of George W. Bush, called exchanges “a strategic pillar of our nation’s public diplomacy.”9 In 2009, Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs Judith McHale said exchanges are “the single most important and valuable thing we do.”10

State’s Dual Relationship with SWT Partners

The exchange structure was established in 1961, when Congress passed the Mutual Education and Cultural Exchange Act. The legislation sought to “increase mutual understanding between the people of the United States and the people of other countries.”11

Propelled by successive administrations, SWT grew dramatically. Its ranks of young participants swelled from about 20,000 in 1996, to 56,000 in 2000, and 88,500 in 2005. Participation peaked in 2008 at nearly 153,000 before the recession caused it to sag – to 132,000 in 2010 and 103,000 in 2011.

While State has the responsibility regulate SWT, the day-to-day administration of the program is the work of some 55 organizations designated by the State Department as SWT sponsors. Many are nonprofit organizations that administer a variety of exchange programs and enjoy tax-exempt status. Some have grown rapidly because of the SWT boom.

The relationship between the sponsors and the State Department is characterized by unusual duality that at times seems schizophrenic.

On the one hand, as the regulator of the SWT program, State oversees the sponsors and must be willing to discipline them when appropriate. On the other hand, State Department officials regard the relationship as a partnership. In 2010 Assistant Secretary of State Ann Stock called the sponsors “our key partner on the front lines of international engagement.”12

Stock made that observation at the 2010 meeting of the Alliance for International Educational and Cultural Exchange, a trade association that lobbies Congress and the State Department for the sponsors, who themselves have a dual approach to their work. They declare an idealistic commitment to building exchanges for the sake of world peace. But they also rake in tens of millions of dollars in fees from the foreign students they bring into the SWT program.

Sponsors’ income has soared in the past decade as the SWT program has grown rapidly and spread around the world. The Alliance’s executive director, Michael McCarry, has said that one of his responsibilities is to lobby for federal “regulations that are permissive and allow people to come to the United States, in a responsible way.”13 McCarry coordinates the sponsors’ work with congressional offices, where they advocate not just for SWT, but for many other exchange programs, including those for high school students, au pairs, camp counselors, teachers, professionals, and others.

In the SWT program the State-sponsor relationship is complicated by the fact that State has allowed the sponsors to outsource much of their work – the screening and selecting of SWT participants and their orientation to life in the United States – to partner agencies in foreign countries that are not under State’s jurisdiction.

Problems with Foreign Partners

In some instances, sponsors have done little more than collect students’ fees as they outsourced much of their work to their foreign partners. And in some instances the foreign partners have proved to be unscrupulous or even criminal.

In 2009, for example, the U.S. consulate in St. Petersburg highlighted the poor screening of a Russian agency by describing one SWT applicant who, “when questioned about why she was not attending university, admitted that she works in St. Petersburg at an erotic services salon.” The consulate found that another agency was using its relationship with a U.S. sponsor to provide job offers “at U.S. companies that no longer existed.”14

Such negligence and fraud were the target of new regulations adopted by the State Department in 2011. Those regulations require that sponsors vet and monitor their sponsors more carefully. Critics have called them “vague” and “toothless.”

Striving to Be “Customer Centric”

As we will see, the sponsoring organizations and their partners have mounted elaborate campaigns to recruit both SWT participants and U.S. employers. Meanwhile, the State Department has complemented their efforts with a spirited boosterism of a sort more commonly associated with the Chamber of Commerce.

A month after State adopted the new regulations to control SWT, it rolled out its new J-1 visa website. In a 2011 webchat with foreign reporters, an official hailed the move as the “first step to revamping our entire Bureau’s web presence to be more customer centric and user friendly.”15

State was enthusiastic about the prospects for further growth and globalization of SWT. In the same webchat, one official noted its blossoming potential in some of the world’s most populous countries with this excited assessment: “Brazil is a very big sending country. A lot of the Eastern and Western European countries are top sending countries. China is definitely growing. India is growing.” SWT is open to the world. Yet the officials assured the foreign audience that the size of the SWT program is determined largely by the marketplace of young foreigners who wanted to participate.

State’s abrupt decision in November 2011 to freeze the number of SWT participants signaled at least a tentative recognition that the program needs also to balance other concerns, including unemployment rates within the United States, the appropriateness of some SWT jobs for a cultural exchange, and the ability of sponsors to do their work responsibly.

At the same time, State announced that it was suspending designation of new sponsors for the program. Nevertheless, more than a month later, State was still declaring on its J-1 website that it “welcomes and encourages new organizations to become sponsors of exchange visitor programs,”16 the largest of which is the SWT.

“Enrich Your Resume” in the USA

SWT has boomed because of a remarkable combination of disparate forces: State Department enthusiasm based on foreign policy concerns, the hunger of young people around the world to come to the United States, intense recruitment by dozens of U.S. sponsoring organizations and their hundreds of foreign partners, and the growing awareness of American employers that the program offers them many benefits.

These forces have propelled SWT to become a worldwide industry whose capacity for growth appears to be virtually unlimited.

The young participants have multiple motivations for signing up. Even at the minimum or near-minimum wages that SWT jobs offer, many earn much more than they could at home. Many are eager to take advantage of the permission they receive to travel for one month around the United States after working for three months. They want to see the sights and improve their English.

The Divan Student Travel agency in Jordan described the SWT magic this way on its Facebook page: SWT “gives you the opportunity to achieve your dream and enrich your resume and work” in the United States.17

To pursue that opportunity, many students borrow heavily, accumulating debts that, according to critics, make them de facto indentured servants.

In his 2011 critique of SWT, Daniel Costa of the liberal Economic Policy Institute noted the report in a Peruvian newspaper that students spend up to $3,000 in fees and travel expenses to get to the United States. Wrote Costa: “This constitutes a huge investment” for a student from a country “where the median disposable family income is only $4,385 per year. He or she will be desperate to earn the expenditure back in wages.”18

As suggested by the Jordanian travel agency, another fundamental force in the growth of SWT is the international infatuation with American popular culture and American mythology of individual freedom and self-reinvention.

A Google search for “Work and Travel” and “J1 Visa” provides some idea of the power and energy SWT has taken on around the world as those twin terms have become part of the vocabulary of university students. In mid-December 2011 the search produced 76,800 matches. They included material from hundreds of websites maintained by sponsors and their recruiting partners, some of which were founded by business people who saw the program’s potential for growth when they were SWT participants themselves.

The websites are splashed with photos of iconic American images: Times Square, the Grand Canyon, the U.S. Capitol, the massive Hollywood sign overlooking Los Angeles. They promise young customers the glitz and glamour and wonder of the United States.

Selling American Cool in Moldova

The Moldovan travel company Student Adventure maintains a high-energy, multicolored website to recruit local college students for SWT jobs.

“Check It Out!” its website beckons on a page featuring a hyper-made-over Statue of Liberty. It is a super-cool version for the hip-hop era, with billowing blonde hair, red lipstick, red sunglasses, and ear buds. Instead of a torch, she holds aloft an ice cream cone. Other images of American cool fade in and out, declaring “Work & Travel, DUDE!” and “Wassup from America, Man!” Plus “See America in 3D” and “Keep Smiling”.19

Student Adventure’s website declares that since it was founded in 2000 it has brought over 5,000 young Moldovans to the United States. With the ardor of a preacher offering the chance to be born again, it proclaims that for many, the program “changed life totally.”

Eager for an American summer, 5,547 Moldovans took part in the SWT program in 2008, when the country entered the list of top-10 sending countries. It was behind Russia, Brazil, Turkey, Ukraine, Thailand, Ireland, and Peru. It was just ahead of Poland, whose numbers dropped steadily after its 2004 entry into the European Union.

Many of the recruiting websites link to YouTube videos. They show J-1 participants at work – sliming fish in Alaska, working the grill at McDonald’s. And at play – body surfing at beach resorts, marveling at the lights of Time Square, drinking and dancing and romancing at parties. The musical backgrounds are as varied as Nirvana, the Beach Boys, the electro-pop of Ke$ha. The videos are a powerful form of SWT advertising, conveying a seductive message of American cool, American opportunity, American freedom, American fun.

Social Media Feeds the Boom

The website of the Ukrainian travel agency Orange Travel touts SWT as a gateway to the “United States of America, the land where you change a lot of views, where people smile and greets each other on the streets; it is much more then crossing the ocean, your independent summer stay in the USA bring up the freedom and self-confidence you never felt before.”20

Orange Travel is one of dozens of Ukrainian agencies that promote SWT. That is a particularly dense concentration, but the SWT phenomenon has exploded in many other countries, with a boost from social media.

There are Facebook pages that broadcast the opportunities and Internet forums that that spread the news, including the story that captivated Andrius Sarkunelis. He is a 20-year-old finance major from Lithuania who told the story while cleaning the counters at Boog’s Barbecue in Ocean City, Md.

Sarkunelis said he learned about the program on a friend’s Facebook page and then used Google to learn more. He said he had a wonderful summer of 2011 and was eager for more. “I hope I can come back next year,” he said, “and I’m going to tell all my friends about this place.”

The young Lithuanian’s enthusiasm for SWT is commonplace among participants, especially in places like Ocean City, which offer sun-drenched opportunities for both work and good times with other young people who come from all across Eastern Europe, and in recent years from China, Mongolia, Thailand, Taiwan, and Colombia.

China entered the top-ten SWT list in 2009, sending 3,152 students. In 2010 the number grew to 5,056. Increasing attention from sponsors and a growing network of Chinese recruiters have the country poised for SWT growth, which will likely be checked – if only temporarily – by the freeze imposed by the State Department.

An Employer’s Dream

The expansion of SWT has been cheered by employers, especially in resort areas where they face the loss of American students who generally return to school in mid-August.

“Our summer doesn’t end then, so we had to come up with a solution,” said Christine Komlos of the Seacrets restaurant and nightclub in Ocean City, where several dozen SWT students supplement the domestic workforce. “We’ve only got 6,000 people who live here year-round. That is not enough people to cover all the summer jobs we have when hundreds of thousands of people come here in the summer.”

The manager of the Carousel Hotel in Ocean City told the Washington Post, “We absolutely couldn’t get through the summer without these kids. They’re great workers. They want every hour you’ll give them. They work second jobs instead of partying, and they don’t all leave on the same day at the end of the season. The entire summer economy of Ocean City has come to depend on European student workers.”21

For employers, SWT offers an array of benefits. Some like the touch of international flair. All appreciate the access to a large supply of educated workers willing to work at close to minimum wage. The tax benefits are also attractive. Employers need not worry about health insurance since SWT participants are required to buy their own. And the program offers liberation from the difficult tasks of recruiting workers by ones and twos.

“CIEE takes all the work out of our hands,” says a grateful manager at Maine’s Sebasco Harbor Resort, in a video posted on YouTube. It was produced by the largest SWT sponsors, CIEE, which is based in Portland, Maine.22

CIEE and the other SWT sponsors get plenty of help from partners like New Jersey-based Seasonal Staffing Solutions. Founded in 2006 by former SWT participant Vadim Misnik from Belarus, it offers employers an international army of inexhaustible young workers hungry to earn dollars. “Most of our students will be happy to work for 60 or more hours per week,” says its website.23

While the sponsors and agencies collect handsome fees from SWT participants, they offer their services to employers for free. “What does it cost to use our service?” asks New York-based InterExchange. “Nothing. As a non-profit organization promoting cultural exchange, our goal is to find exceptional staff for your business, and to help international students experience life in the United States.”24

Here’s the pitch of a Russia-based recruiting firm: “Hiring international exchange students … is now absolutely easy for your firm. You inform us about your needs, we select and submit the applications for you to consider and we do the rest of the hiring procedure for you.”25

Many sponsors and recruiters point out SWT’s cost-cutting tax benefits. Several of their websites include a “tax calculator” that allows them to tally what they save by hiring foreign workers.26

Seasonal Staffing Solutions claims that by hiring five SWT students instead of “regular workers,” i.e. Americans, for the summer season, an employer can pocket an extra $2,317.27

But wait, there’s more, as TV pitchmen like to say. Sponsors also make sure that employers know that despite a widespread impression that the Summer Work Travel program is limited to the summer, the reality is that the program offers “Year-Round Availability.” The pitch of InterExchange is typical: “Because we recruit students from all over the world we can fill positions at any time of year.”28

“It’s all perfectly simple,” declares the website of JobOfer.org, which was founded in 2003 by Ruslan Lysak, who was an SWT student nearly a decade ago when he was studying applied mathematics at a Russian university. “Just register, review the profiles of international students we’ll be sending, and don’t worry about the rest.”29

Wooing Employers with Free Trips

The sponsors’ pitch to employers isn’t limited to touting the free recruitment of workers, their willingness to work for minimum wage, and tax exemptions. Many offer recruiting trips to Europe, Asia, and South America so employers can interview prospective SWT employees and sign them up on the spot.

Consider Chicago-based CCI, which declares that its mission is “the promotion of cultural understanding, academic development, environmental consciousness, and world peace.”30 In the fiercely competitive business of SWT sponsorship, CCI offers packages to employers to “travel to exciting destinations in Brazil and Argentina to interview pre-screened applicants.” For employers who hire a certain number of workers through CCI, the trips are free.31

Employers who don’t sign up for the overseas travel have another option. CCI will fly them to Chicago for a “virtual job fair” that allows them to conduct remote interviews with students who are pre-screened by CCI’s overseas partners.

This is the pitch: “CCI brings you to Chicago to complete your hiring process and to enjoy our wonderful city! Not only will CCI provide a venue and guidance for your international interviews, we also offer accommodations at a boutique hotel, a delightful excursion, and an opportunity to get to know our staff!”

That staff includes Debbie Best, a Senior Employer Relations Specialist touted on the website as a woman whose “extensive experience in the radio and entertainment industries and in HR outsourcing ensures that the CCI J-1 Work and Travel program brings the world to the workplace.”32

Best not only arranges to take employers overseas, she also rewards the most active participants in the SWT with other incentives. She picks up the tab for round-trip airfare, four nights of hotel accommodations, and three days of skiing in Wyoming as part of the “Jackson Hole Experience.”33

Consider the pitch from InterExchange, which describes itself as “a non-profit organization devoted to promoting cross-cultural awareness through work and volunteer exchange programs.”34 In the late summer of 2011 InterExchange was touting its upcoming two-week trip to hire workers for summer 2012. The itinerary included stops in Moscow, Istanbul, Belgrade, and Paris, with a day for sightseeing at each location.

“You can visit one country or all four on an all-expense-paid trip designed to help you meet and recruit the best international summer staff in the world,” InterExchange promised. “You’ll have the opportunity to experience these unique cultures up close, and gain a better understanding of the students you’ll be hosting and the customs of each country.”35

Employers who hired 50 or more workers through Interexchange would travel for free – in business class to and from Europe and standard fares in between. Those who hired 15 would travel free to one country. For employers who were not interested in traveling, but who would hire at least 10 workers, InterExchange offered its “virtual recruitment tour,” which brings them to the sponsor’s New York offices to interview and hire in a video conference. “Travel, accommodations, dinner, sightseeing, and entertainment are all included during your stay in New York City.” Cost to employers: nothing.

Preparing the Next Generation

While SWT has become a lucrative industry, its sponsors declare a higher motivation. They profess a commitment not only to international understanding but also to the preparation of young people for international competition.

“Today’s global markets require international work experience, and the value added by working in the USA is immeasurable to students from overseas,” says Texas-based Alliance Abroad.36

The International YMCA proudly declares its mission to “provide an opportunity for young people from around the world to challenge themselves through learning to work, grow, and live in another culture.”37

Virginia-based Janus International Hospitality Student Exchange proclaims that its mission is “to provide our participants from around the world a cultural exchange program while helping them gain the necessary skills to succeed in today’s global economy.”38

When Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke about work on an Alaskan “slime line” as preparation for Washington, she was joking. But the experience, which included being summarily fired after she complained about sanitary conditions at the plant, was valuable to her on several levels. Biographer Roger Morris writes that her trip to Alaska was an “act of restless independence” against the wishes of both friends and family. He adds that she came “back from the Northwest with a new air of self-sufficiency, if not cynicism” and then “confidently enrolled as one of the few women at Yale Law.”39

It is ironic that as SWT has expanded around the globe, it has given foreign students work opportunities once seized upon by young Americans. The irony is intensified by the fact that the program is administered by the State Department, which is managed by a woman who struck out to Alaska as a way of preparing herself for the challenges that awaited her. Today in Alaska, a summer worker in a fish processing plant is more likely to come from the Ukraine, Russia, Bulgaria, Moldova, or Turkey than from Illinois.

Young Americans "Don't Know How the System Works"

As the 2011 summer season in the beach resort town of Ocean City, Md., wound down in early September, a server at the Fish Tales Restaurant told of observing the bewilderment of job-seeking young Americans as they encounter the power of the Summer Work Travel (SWT) program.

“American kids will come in May when the season is just getting started, and we tell them, ‘Sorry, we’re all full,’” said Trina Warner. “And they say, ‘Already?’ They have no idea that foreign students have already been hired,” she said.

Then she added, “They don’t know how the system works.”

The robust, innovative, and lucrative system of worldwide recruitment for the Summer Work Travel program dwarfs efforts to recruit young Americans. To paraphrase Mark Twain’s observation about the speed advantage that a lie enjoys over the truth, SWT employers can line up their summer workforce halfway around the world before American students put away their winter boots.

The largest SWT sponsor, the Council on International Educational Exchange, boasts that it works with “a network of over 70 representatives in 50 countries.” It sponsors about 25,000 SWT participants each year. Its website assures employers that CIEE “can help you meet your hiring goals well in advance of your busy season.”40

While SWT has become a lucrative worldwide industry for sponsors, for some it is also a labor of love and good will. There may be no better example of this altruism than Anne Marie Conestabile, the regional manager for CETUSA in Ocean City. Expressing an opinion that appears common among SWT students, Daniela Pascau of Romania said of Conestabile: “She is very kind; she has a good heart.”

CETUSA hired Conestabile after learning of the volunteer work she performed to help bewildered J-1 participants whose negligent sponsors had sent them to the beach resort and then abandoned them. Others were broke and distraught, having been conned by home-country agencies that fraudulently sold them access to jobs that did not exist.

“I found myself embroiled in these horror stories of false job offers, students left unattended – no housing, no money, and no food,” Conestabile said at her office two blocks from the beach.

Working through her church, she drew other volunteers to pitch in. “I said, ‘Let’s welcome them instead of just dumping them.’” Later she helped establish Ocean City’s SWT task force, which brings together sponsors, employers, and city officials in an effort to establish order in a program that had become chaotic in its freewheeling growth.

The State Department’s own Inspector General discussed such negligence in a 2000 report critical of State’s management. “Some sponsors of J Visa participants may be motivated by the income that can be derived from the J Visa,” the report said. It quoted representatives of the international partner agencies as freely acknowledging: “It’s a business.”41

Conestabile takes an almost maternal pride in the progress of her young charges, whom she places in restaurants, hotels, amusement parks, and shops that swell their employment rolls in the summertime.

“They grow so much when they’re here,” she said. “They learn to make their own decisions. They become independent from family control. And they go home feeling proud. You have no idea the transformation I see every year. When they start out they’re walking in feeling timid and worried. Three months later they are so proud and so confident and their English has improved tremendously. These are things I love about the program.”

SWT clearly provides benefits to students, employers, sponsors, and their partners. The State Department believes that its value in U.S. foreign policy is also considerable, since all SWT participants must be college students and some could eventually become leaders in their own countries.

But when State’s partnership with an industry that it regulates has produced the rapid growth that SWT has experienced over the past 15 years, it is reasonable to ask what effects that growth has had among young American workers, who have no lobby and are not the objects of robust and sophisticated recruitment.

In the name of cultural exchange and international understanding SWT has denied or curtailed a place in the workforce for many American high school and college students who are thereby denied an important opportunity to work and grow within their own country.

Sarah Ann Smith gives a tally of how the arrival of J-1 students affected her teenage son’s dishwashing schedule at a restaurant in Camden, Maine: first week, 24 hours of work; second week, after the arrival of two SWT workers, eight hours of work; third week, when the SWT staff totaled six workers, zero hours of work.

Said Smith, “He was told by the restaurant manager that according to the contract with the foreign kids, they had to get a minimum of number of hours, so he was out of luck.”

Ironically, Smith is a former State Department Foreign Service officer who endorses the philosophy that underlies SWT: “I think the best way to convince the rest of the world that we’re not bad guys is for them to come here and see the United States,” she said. “But it’s wrong to have a program that allows foreign kids to come in and take jobs that American kids need.”

Assessing the well-established presence of SWT in her hometown, Smith added. “There are American kids sitting around on the sidewalk and hanging around complaining that they can’t get work. And there are foreigners who have jobs they could do. And in this economy there are foreigners in jobs that young adults would like to have. Instead, we’ve got kids saying, ‘I’m leaving Maine, there’s no jobs here, there’s nothing for me here.’ It’s a real problem. The [SWT] program is out of control.”

It is difficult to gauge the frequency of such stories. The number of SWT participants is small in relation to the overall workforce of young Americans. But the impacts can be significant, particularly in areas of the East Coast, where the program tends to concentrate many of the young foreigners.

The complaints have been building for years. In 2002 an indignant reader of the Hartford Courant wrote a letter to the editor suggesting that the SWT program be renamed “Importing Unneeded Cheap Labor.”

The author took note of the price paid by American young people when employers are committed to hiring foreign workers. He said he was “the father of a disillusioned teenager who, in the summer of 2000, found herself working a part-time job at Six Flags New England instead of a full-time job. The arrival of foreign workers two weeks into her employment led to a 50 percent reduction in her hours.”42

In Ocean City, Maria Raymond, a student at nearby Wor-Wic Community College, is a member of a rare group: an American employee at the many Dunkin Donuts shops along the coast of Maryland and Delaware. Those shops are largely staffed by some of the more than 20,000 young Russians who participate every year in the SWT program.

“I think (SWT) definitely makes it harder for American kids to get jobs,” said Raymond. “I mean, if all the foreigners are working, that means there aren’t jobs for Americans to find.”

Holy Cross College student Jessie Frascotti described losing a job because of a competitive disadvantage that employers often cite as a reason for hiring the foreign students: their school schedules allow some to arrive in early May and some to remain until October.

“This summer I came back to Martha’s Vineyard expecting to have the same job I did last summer, but it had been given to a foreign student who arrived earlier and stayed longer than I could,” she said in an e-mail. Frascotti eventually found work on Martha’s Vineyard, in a commercial area where SWT workers from Poland, Romania, Belarus, and Moldova and other countries worked in shops and restaurants and grocery stores.

Jobless in Boston

Last June, as hundreds of SWT participants were filling jobs on Martha’s Vineyard and nearby Cape Cod and as SWT students from Eastern Europe took jobs in Boston for moving companies and other employers, the Boston Herald was reporting that 1,400 local teens were expected to be unable to find summer jobs because of cuts in state and federal jobs programs. “We are still trying to find every job we can,” said Conny Doty, director of the city government’s Office of Jobs and Community Services.43

And as the summer ended in September, the Boston Globe reported that the cutbacks meant that “about 2,000 teens who would have been employed for at least six weeks went without paychecks.” Neil Sullivan, executive director of the Boston Private Industry Council told the paper, “There are plenty of teenagers ready to work. It’s just getting the adults together to organize it."44

In some instances, the frustration Americans feel at the State Department-sanctioned competition for jobs is muted by their admiration of the young foreigners’ work ethic and by the opportunity to learn about their home countries.

“I almost feel like some of them deserve the job more than I do because I do feel like some have a better work ethic than I do,” said Frascotti. “I did work with mostly foreign students last summer and they would come in, work hard from like 8 to 5 or 6 then go to their second job and work to 11.”

This hunger for work among SWT participants intensifies some employers’ dismay at the work habits and attitude of young Americans. Some, like the following three from Ocean City, offer a litany of criticism.

Employers Complain about Young Americans

Said Patricia Smith of the Castles in the Sands Hotel: “They don’t want to work weekends. They want to take a lot of days off. They’re always on their cell phone, always want to email and chat. You have to get them to understand that work time is not social time.”

Said Jon Tremellen, manager of the Princess Royale, where J-1 students fill the housekeeping crew: “American kids don’t want to make beds. That’s not what they’re interested in. They want to make a couple hundred dollars a night waiting tables.”

Said Christine Komlos of Seacrets, an Ocean City restaurant and nightclub: “They want to work when they want to and that’s it. They give you a laundry list of days they want off. For a lot of them, they don’t even have the desire to earn money. That doesn’t motivate them. When I was their age and worked in Ocean City, everybody fought for extra shifts because they wanted to make that money. I know I’m stereotyping but probably 75 percent are that way. If I say it’s not as busy as we thought so a couple people can go home, they’re fighting to be the people to go home, not the people to stay. I don’t understand it.”

Such criticism isn’t confined to employers of older generations. “I’m not sure that most American kids have been taught a good work ethic,” said Cory Balar, a Virginia Tech computer science student who worked two jobs in the summer of 2011 at Fenwick Island, Del., just north of Ocean City. “A lot of my friends don’t really need to work. They just do it because their parents tell them to go get a job, and then they don’t want to work a lot of hours.”

Melanie Pursell of the Ocean City Chamber of Commerce has heard many of her colleagues comment on the contrast in work ethics. She pointed to a built-in feature of the SWT program as a possible explanation. “This could be due to the fact that they pay a hefty price to participate in the program, and therefore have a very good reason to work their hardest, to be able to pay back the program fees.”45

Questioning the Effort to Recruit Americans

Asked about Ocean City’s efforts to recruit American youngsters for summer jobs, Pursell pointed to the job fair held every spring in the coastal resort. She said that in addition to advertising in local newspapers, job fair promoters put out the word to high schools and colleges within a 300-mile radius. “We do send posters to all of the colleges – mostly their career centers,” she said.46

One Ocean City employer whose policies require that it hire U.S. citizens has been far more ambitious in its recruitment. The Ocean City Police Department visits about 30-35 college campuses to hire its 100 seasonal workers, said Officer Barry Neeb. Police recruiters fan out across Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, he said.

About 120 miles south of Ocean City, columnist Roger Chesley of the Virginian-Pilot newspaper expressed alarm at the growth of the SWT program in Virginia Beach. In a 2010 column he wrote that a Dairy Queen owner told him: “There are some good American kids, but eight out of 10 are not reliable.” Another employer told Chesley, “If J-1 didn’t exist I don’t know what we’d do.”47

Countered Chesley: “Companies could do more outreach for one. They could list the job openings at local colleges and contact officials at high schools.” Neither of the complaining employers was doing such outreach, he wrote.

Of course, one reason that American employers’ recruitment is so weak is that the recruitment done for them by the SWT industry is so strong. While Ocean City is sending out posters to East Coast campuses, SWT sponsors are taking employers to job fairs at universities across Europe, Asia, and South America.

At a 2010 job fair in the Ukraine, Anne Marie Conestabile made this pitch: “Ocean City is a heaven for young people. We have eight to 10 thousand young international students who come to Ocean City every summer, sporting their bikinis, sporting their tans, and making money.”48 Her CETUSA colleagues, meanwhile, promoted jobs at locations from the Hershey amusement park in Pennsylvania to desert resorts in Arizona to fish processing plants in Alaska.

Drastic Decline, Long-Term Consequences

The globalization of the SWT workforce has occurred at a time of drastic decline in work among American young people.

In the spring of 2011, the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University reported that from 2000 to 2010 the employment rates for 16- to 19-year-old Americans had fallen drastically. While more than half had jobs at the beginning of that period, about one in four had jobs at the end. “The size of these declines has been incredible,’’ said the Center’s Andrew Sum.49

The consequences can be debilitating in the long run. Steven Camarota of the Center for Immigration Studies notes that “The fall-off in youth employment is worrisome because research indicates those who do not work when they are young often fail to develop the skills necessary to function in the labor market, creating significant negative consequences for them later in life.”50

There are multiple explanations for the drop that go beyond the circumstances of the SWT program, or the use of foreign workers more generally. Many young Americans go to summer school. Some seek out unpaid internships. They and their families view summer as a period for gaining a competitive advantage in career building.

But a booming J-1 program that has habituated more and more employers to hire foreign students has clearly depressed job prospects for young Americans, especially in areas where that growth has been most intense.

One American entrepreneur who has made a go of it is Renee Ward, founder of Teens4Hire.org. Ward said she started her business in 2002 because as the parent of a teenager she saw there was no systematic outreach to hire them. “I found it was a haphazard process for American young people to find work,” she said.

Ward is angry at the growth of the SWT program, which she says displays a selfish disregard for the well-being of young Americans. She says she is frustrated at being rebuffed by employers from Cape Cod to Florida to Nevada: “They say ‘we’re okay; we just increased the number of J-1 kids that we’re hiring.’“

Ward has watched the expansion of SWT with dismay and disbelief. “These programs need to be revised in light of the status of American kids,” she said.

Culture Clash: The Hershey Legend Meets SWTThe Hershey Company revels in the legacy of its iconic founder, Milton S. Hershey, who is described in a highly regarded biography as an extraordinary man who “was able to fulfill the progressive utopian ideal of using the fruits of capitalism to raise the spirits, and the standard of living, of all involved in his company.”1 The company’s chocolate marketing still invokes that remarkable history, which includes Mr. Hershey’s decision to gift all his stock to sustain the school he founded for needy boys. A company press release in 2010 noted that legacy, adding: “Simply put, every time someone enjoys a Hershey’s product, they are helping to foster opportunity.”2 Hershey, Pa., calls itself “the sweetest place on earth.” So it was a bitter embarrassment for the company to be the target of a summer 2011 protest by about 200 young workers at its mammoth distribution center just east of the town that carries the founder’s name. The dissident workers were all foreign students – from such countries as Turkey, Ghana, Russia, China, and Moldova – who were in the United States with J-1 visas as part of the Summer Work Travel program. A New York Times story about the protest began this way: “Hundreds of foreign students, waving their fists and shouting defiantly in many languages, walked off their jobs on Wednesday at a plant here that packs Hershey’s chocolates, saying a summer program that was supposed to be a cultural exchange had instead turned them into underpaid labor.”3 The students’ complaints – that they were underpaid, overworked, overcharged for housing, and cut off from everyday contact with Americans – were spread around the world in a barrage of print and television stories. Often the news included photos of placards demanding “Justice @ Hershey’s” and “No More Captive Workers.” “There is no cultural exchange, none. It is just work, work faster, work,” a Chinese student told the Times, which published an editorial saying the students’ plight “should shame us all.”4 Complaining about working a shift that began at 11 p.m., a Ukrainian student told the Associated Press, “All we can do is work and sleep.”5 Many students complained that other workers spoke only Spanish. One told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “I wanted to improve my English, but I have only improved my muscle.”6 Horrified officials at Hershey pointed out that while the company owned the plant, it had contracted out with another company to operate it. That company, in turn, noted that it had hired yet another firm to staff the plant. And the staffing company turned to an SWT sponsoring organization to bring in many of its workers – about 400 in the summer of 2011. The staffing company’s website told part of the story. It said clients typically face “increasing, unrelenting pressure to improve performance, drive down unit costs, and increase return on investment.”7 That hard-nosed orientation presented a stark contrast to the benevolence of Milton Hershey, whose words are memorialized on the walls of the Hershey Museum. Reads one quotation: “I have always worked hard, lived rather simply, and tried to give every man a square deal.” The museum shows a film that celebrates Hershey’s resolve to “create an ideal place for his workers and their families,”8 allowing them to escape the brutality and harshness characteristic of life for industrial workers of his era. The multi-level arrangement at the Hershey plant surprised many observers who became aware of it after the foreign students launched their protest, with financial and organizational support from the Service Employees International Union and a group called the National Guestworker Alliance. “It appears that the cultural exchange students were trapped in a tangled web of outsourcing and bureaucracy at its worst,” said a Philadelphia Inquirer editorial. “The candy makers apparently turned a blind eye to what the students … were experiencing until the controversy erupted.”9 The protestors aimed much of their criticism at the organization that sponsored the J-1 students. The Center for Educational Travel USA (CETUSA) had worked with agencies in the students’ home countries to recruit them, help them obtain visas, and make travel arrangements. “They told us the job would be easy and fun and they would have pizza parties for us,” a Turkish student told the Washington Post. Other students complained that CETUSA was charging $2,000 for five of them to share apartments that normally rent for far less.10 Some commentators, noting the State Department’s vision of the program as a showcase of American life, suggested caustically that the SWT workers were indeed getting a realistic view of how many Americans lived their lives. “Hate to tell you,” said a letter to the editor of the Patriot-News in nearby Harrisburg, “but you are experiencing America in the same way many Americans are experiencing America.”11 More acerbic commentary came from RT, The Russian government-financed English-language news channel, whose reporting is often colored by schadenfreude about the social, economic, and political problems of the United States. For its story about the students taking their protest to New York, RT offered this comment:

That final point was a centerpiece of the protest, as students expressed solidarity with unemployed Americans. “They take students who came on a cultural exchange to slave for them and make next to nothing, when these jobs could be going to families in Pennsylvania,” a Nigerian medical student told the New York Times.13 Stunned by the publicity blitz that mocked Hershey’s image of corporate benevolence, a company spokesman said the students should be given a week of paid vacation so that they could see other parts of the United States. “We were disappointed to learn that some of the students were dissatisfied with the cultural exchange element of the program,” said spokesman Kirk Saville. He added, “We want to ensure that all the students have a positive experience of this program and leave the United States with an understanding of the Hershey Company.”14 Any understanding of the company would have to consider its efforts in recent years to cut costs. The production plant it opened in Mexico in 2008 took about 600 jobs from its home town. And when Hershey completes construction of the highly automated new candy factory coming to the edge of town, several hundred more jobs will be lost. The director of the National Guestworker Alliance, the group that organized the students with the help of labor unions, was not in an understanding mood. He said the protest exposed “how companies like Hershey’s are getting creative in their search for the cheapest possible labor, using the J-1 cultural exchange program, which was never intended to be a guestworker program, to fill what used to be living-wage jobs for local workers.”15 The protest embarrassed not only Hershey but also the State Department, which launched an investigation, with particular attention to the work of the students’ sponsor, CETUSA. The executive director of the organization that lobbies for exchange program sponsors issued a statement welcoming the investigation and expressing confidence that the problem “will be assessed for what it is: an unusual, unfortunate event in a very successful program”16 CETUSA’s response to the State Department included documents to show that before coming to the United States, each student had signed a contract that described in detail the strenuous nature of the work. It explained that the $400 per month it charged each student for housing was necessary to overcome landlords’ reluctance to rent to students for a short period of time. It denied that it was making money on the arrangement. And it said that students who worked the night shift had chosen that schedule, frequently because they hoped to find a second job during the day.17 By the time the furor died down and the students returned home in the fall, SHS (the staffing company) had announced that it would no longer employ SWT students at the plant. The State Department continued its investigation. And CETUSA announced that it was closing its regional office in nearby Harrisburg and pulling out of the central Pennsylvania market, which it had begun to develop a decade earlier when it began supplying SWT workers to the Hershey amusement park and nearby hotels. But CETUSA lost the Hershey Park account at the end of 2010, when regional manager Agata Czopek, who had recruited heavily in her native Poland, began working for the Harristown Development Corp. and took the Hershey account with her. Harristown officials have been aware of the growth of SWT and of its potential for growth in central Pennsylvania for some time. In 2008, Harristown executive Brad Jones invited Czopek to participate in a discussion at the Harrisburg campus of Penn State University that was titled “The Work & Travel Visa – How it’s Changing America’s Workforce.”18 Harristown has pursued a sort of vertical integration of J-1 participants. It hires them to work at its Hilton Hotel and the Bricco restaurant. It houses students at a residential property it owns. And in 2010 it established the International Institute for Exchange Programs, which it hopes will receive State Department designation as a SWT sponsor. Czopek, the director of the institute, did not respond to phone calls and emails. But she and the Institute clearly hope to expand the SWT program in the Harrisburg-Hershey area. In the summer of 2011, according to the Patriot-News newspaper, the program had placed participants at 22 business locations in the area, including the Harristown and Hershey sites, and the nearby Warrell Candy factory.19 In the spring of 2011, Independent Joe, the magazine for Dunkin Donuts franchise owners, published a story about owner B.J. Patel’s recognition that the program “can work for seasonal hiring, but can also provide coverage pretty much all year round, with students coming every four months or so. ‘I figured that I’d try it for the year,’ Patel said. ‘I wanted to see if it could work.’”20 The former mayor of Harrisburg, Stephen R. Reed, criticized SWT as inconsistent with the Obama administration domestic agenda: “In times of economic distress, you can’t have the Department of Labor and other departments calling job creation the number-one priority and then simultaneously have the State Department not just ignoring that but working in a contradictory manner.” Reed said that while the SWT program can work well in areas of low unemployment, it should not be authorized in areas where unemployment is a significant issue. Given the high unemployment in the Harrisburg area, he said, SWT should be authorized there “only on a very limited basis at this time.” Reed said that while he supported cultural exchange, “I would not do it at the expense of unemployed Americans.” 1 Michael D’Antonio, Hershey: Milton S. Hershey’s Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams, New York, Simon and Schuster, 2006, p. 158. 2 PR Newswire, “Hershey’s Milk Chocolate Bars Now Contain Special ‘Thank You’ Message; Hershey’s Milk Chocolate Bars and Milk Chocolate Bars with Almonds to Deliver a Sweet ‘Thank You’ to Consumers who Have Supported Children in Need.” January 4, 2010. 3 Julia Preston, “Foreign Students in Work Visa Program Stage Walkout at Plant”, The New York Times, August 18, 2011. 4 “Not the America They Expected”, The New York Times, August 19, 2011. 5 Mark Scolforo, “Foreign workers for Hershey protest Pa. conditions”, Associated Press, August 19, 2011. 6 Tom Barnes, “Foreign Hershey Workers Continue Protest”, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 20, 2011. 7 http://www.shsjobs.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3&It.... 8 “Building a Place to Live, Work, and Play” film shown at the Hershey museum. 9 “Students say Hershey treated them like serfs”, Philadelphia Inquirer, September 3, 2011. 10 Pamela Constable, “Foreign students allege abuses in visa work program”, The Washington Post, October 30, 2011. 11 Cyndi Roush, letter to the editor, Patriot-News, September 6, 2011. 12 http://www.cis.org/kammer/russian-news-hershey-protest-american-values. 13 Julia Preston, “Pleas Unheeded as Students’ U.S. Jobs Soured”, The New York Times, October 16. 2011. 14 Brad Rhen, “Agencies probe Palmyra-area plant,” Lebanon Daily News, August 24, 2011. 15 Chris Sholly, “Human rights report calls for probe of J-1 program”, Lebanon Daily News, September 6, 2011. 16 Nick Malawskey, “Officials begin inquiry into Hershey strife,” Patriot-News, August 23, 2011. 17 CETUSA response to claims by Hershey protest, signed by vice president Kevin Watson, addressed to Under Secretary of State Ann Stock, August 21, 2011, http://www.cetusa.org/public/assets/download/38/state-department-respons.... 18 Message from Agata Czopek, published in Chatter, the CETUSA in-house publication, May 2008, p. 3. 19 Nick Malawskey, “The Hershey Co.: Give foreign students paid vacation”, Patriot-News, August 24, 2011. 20 Brooke McDonough, “International Travel Agencies Offer Hiring Solutions and More”, Independent Joe, Issue 8, March 2011, p. 5. |

SWT in Alaska: Fish Sliming as Cultural Exchange

At a job fair in Ukraine in 2009, representatives of Alaskan seafood processing plants were blunt about what they wanted from the Summer Work Travel workers they were about to hire.

“We’re looking for hard workers who are not afraid to work every single day, up to 16 hours a day,’’ said Sarah Russell of Leader Creek Fishing in the village of Nakenak. “You will make a lot of money in a very short period of time and you won’t spend it anywhere because there’s really nothing to do in Nakenak, other than work.”51

Said Branson Spears, who was recruiting workers for plants in Sitka and Craig, “It’s going to be a lot of hard work. It’s going to be long hours. It’s going to be wet and cold. It won’t always be fun, but it’s fun sometimes.”

On its website recruiting workers for the same jobs, the Kazakhstan Council for Educational Travel is no less blunt, saying the job requires a willingness to “work 16 hours a day, seven days a week for cleaning, cutting, and packaging of frozen fish … . Able to endure four months of harsh climate of Alaska and the absence of any entertainment.”52

And a comment in the “Work and Travel” forum on the website of one of the Turkish recruiting agencies issues this warning: “Alaska is not for everyone – must be able to endure cold, odors, blah.”53

Despite those warnings, the Alaskan jobs are popular among students from Ukraine and many other countries who want the work. At a second job fair in Ukraine, processing plant owner John Kelly identified the reason. “What does fish smell like?” he asked rhetorically, brandishing a wad of dollars. “So if you want to smell like fish, come and see us.”54

Appeals like that are persuasive to young men like Petyo Minchev, who studies tourism at a Bulgarian university. He was grateful for a job that required him to work eight hours of straight time followed by eight hours of overtime on a seafood processing ship anchored just offshore in Dutch Harbor.

“Almost all the people in Bulgaria make very little money,” he explained. A factory worker might be paid a monthly wage of $300. So he jumped at the opportunity in Alaska and shrugged off the routine he described as: work 16 hours, shower, eat, sleep for six hours, repeat. He lived aboard the ship Northern Victor from the middle of June until late August, seldom going ashore. “Even if you go on the land, there is nothing to do in Dutch Harbor,” said Petyo. He is one of about 70,000 Bulgarians who have worked in the SWT program over the past decade.

The Vanishing Americans

Laurie Fuglvog of the Alaska Department of Labor offers a concise summary of the growth of the SWT program in her state’s seafood processing plants. She said the students began coming in the late 1990s, when the traditional summertime flow of college workers from “the lower 48” states had slowed.

“Maybe they could make more money somewhere else or maybe there were less people who grew up doing manual labor,” she said. “Then someone started thinking about the J-1s. And then it became the normal thing.”

The person most responsible for the transformation is Brian Gannon, who brought over the first J-1 students – from Russia – in 1998 when he was helping to run a seafood processing plant on Kodiak Island. Before long, Gannon began working as a contractor for other plants, where managers had learned of his success in drawing SWT workers.

On a recruiting trip to Polish universities, Gannon met Rick Anaya of the Council for Educational Travel, USA (CETUSA). At the time CETUSA’s income came from matching American families with foreign students who came to school in the United States.

Tapping Gannon’s enthusiasm for SWT and his Alaska connections, CETUSA began a decade of rapidly expanding involvement in the program. In 2010, CETUSA’s 5,637 SWT participants outnumbered its high school students by more than six to one. About 2,000 SWT participants went to Alaska fish processing plants. Over the previous decade its revenues grew from $2.3 million to $7.6 million.

Gannon said the growing SWT program filled a void caused by young Americans’ declining interest in Alaskan jobs, which he tracked as a processing plant manager. He attributes it to an attitudinal shift that began with the “millennials,” those born after 1980. He was trying to recruit them in the late 1990s, when they were of college age.

“I think that was the golden age of the entitlement population,” said Gannon. “I don’t think people want to enter the workforce at a low level anymore. I think there’s a sense of, ‘I’m entitled to have a management position and I’m not willing to work to get there.’ It’s a generational thing.”

Gannon contrasts the experience of recruiting American college students with the response he receives overseas.

“I can spend a thousand dollars and go to the University of Montana, set up a table, spend some money to advertise in the campus newspaper, and end up begging to sign up two or three people,” he said. “I have done that numerous times. But if I go to the Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia, China – any of the 28 countries I’ve recruited from – these kids are begging me for an opportunity. They’re telling me they will be the best worker I have ever seen.”

Gannon says that in his job as CETUSA’s director of business development he now places workers in 30 seafood processing plants that stretch across an 1,800-mile coastal arc from the Aleutian Islands eastward and southward to Ketchikan. He said he has about 95 percent of the SWT seafood business in Alaska.

But Gannon’s success in expanding the franchise of the State Department’s SWT program has brought it into a thus-far subdued clash with some staff at the Alaska Department of Labor, whose official mission is to “foster and promote the welfare of the wage earners of the state and improve their working conditions and advance their opportunities for profitable employment.”55

Dissent at the Alaska DOL

Brad Gillespie of the DOL criticized the SWT program to Alaska public radio reporter Daysha Eaton, questioning whether it was working as it is supposed to. “If it is working the way it was intended, it’s having a negative impact on U.S. and Alaskan workers. If you’re in a rural community that’s got a plant or two and that’s one of the major employers there and they’re bringing in all outside workers, there’s got to be an impact on those individuals not being able to get on at those plants,” Gillespie said.56

Gillespie declined to be interviewed for this report. But one of his colleagues did speak, asking that he not be named. “It’s a bad thing,” he said bitterly. “I get calls from Americans in other states every day begging for cannery jobs, and we’ve got canneries where none of the workers even speaks English.”

An SWT critic on Kodiak Island who is eager to go on the record is Monte Hawver, who runs the Brother Francis Homeless shelter there. Hawver is upset on several fronts, from the living conditions of the foreign students, to the incentives SWT provides for local canneries to bypass American workers, to what he calls the devastating financial consequences for local families forced to seek assistance from social service agencies.

Hawver says that in an industry subject to the vagaries of the catch, employers jump at the opportunity to reduce payroll costs by hiring SWT workers and taking advantage of the exemption on Social Security, Medicaid, and federal unemployment taxes.

“They are saving 8 percent on the wages of every one,” said Hawver. “So you take that and multiply it by 100 people and by whatever hours they’re working. Over a whole summer that’s a sizable amount of money.”

Hawver said he became aware of the system because of the habit of the J-1 workers – many of them from Turkey – to buy a bike. “If you take a ride after supper and you see dozens of bikes parked out front of a cannery, they might as well put a sign up that says ‘Turks only’.”

The consequences for local families were devastating this year, when the pink salmon run was well below expectations. The Kodiak Daily Mirror reported that even many of the guest workers were struggling. Hawver said incomes for some local families were wiped out. “They’ve got nothing to eat. This is whole families I’m talking about. It especially strikes me in the gut when a mother calls me up and says can she bring down her kids so we can feed them.”

Hawver is angry at the fish processing plants. He is also angry at the federal government for what he sees as a program that is blind to the suffering it is causing for Americans. “They call this cultural exchange. That’s bullshit,” he said. “Excuse my language.”

Defending SWT

Gannon makes two points in response. First, he did not bring the Turks to Kodiak. Second: Kodiak is not representative of the overall situation in Alaska.

“I refuse to believe that we are doing a disservice to this economy,” he said. “If we were not filling these jobs – we being the Summer Work and Travel industry that has developed – these jobs simply would not be filled in Alaska. And if you can’t find a workforce you can’t produce… . Every year the jobs are posted at the Alaska Department of Labor and at the job centers in Anchorage and in Southeast Alaska and in Kodiak. And no offense to the people who show up there, but you get some of the dregs of society. You get meth heads who are looking for another score and you get the people that last a week on the job. Domestic recruiting for production work is very hard. You can spend a lot of money on recruiting and start going backwards.”

So Gannon, the founder of the program, has continued to build it, convinced of its value. In November of 2011 he was planning to lead recruiting tours to some of the countries that have built the wave – Russia, Poland, Turkey, Ukraine – as well as to some countries whose potential is only beginning to be developed including China, Mongolia, Slovakia, and Kazahkstan. “I will be putting employers in front of workers from probably 20 countries,” he said.

Gannon’s frustrations with domestic recruiting are echoed by Mandy Griffith, of Silver Bay Seafoods in Sitka. Griffith says flatly that she would prefer to fill her jobs with Americans. “I’m a believer in trying to keep the jobs domestic,” she said. “But I’ve tried it and we just didn’t seem to get the interest. Then when we went to Poland, I spoke to over 2,000 students at events we arranged with our agent over there.”

The Decline of the Minimum Wage

While there are many differing views about the willingness of the current generation of American young people to work, one fact about the work itself is undeniable. It simply doesn’t pay nearly as well as it did in the decades when a summer job in Alaska was considered a prize for American college students. But the prevailing wage in seafood processing and many other SWT jobs is the minimum wage, and that level of income hasn’t come close to keeping up with inflation.

In 1969, when Hillary Clinton was sliming fish, the minimum wage in Alaska was $2.10. But, because of inflation, what $2.10 could buy in 1969 costs $12.98 in 2011. Meanwhile the Alaskan minimum wage in 2011 was $7.75. That means even the time-and-a-half scale that is so attractive to J-1 workers doesn’t have the buying power that the minimum wage had in 1969.

Moreover, the SWT program’s tax exemptions provide foreign workers with a built-in salary booster, increasing their advantage over young Americans.

After taking over management of the Exchange Visitor Program in the summer of 2011, Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary Rick Ruth indicated some concern about the appropriateness of fish processing in Alaska for a cultural exchange program. Reminded that the work is attractive to many young foreigners despite its isolation and long hours, he said, “It is very attractive. But just as the Summer Work Travel program was not created to provide cheap employment for American employers, it was also not created to be a get-rich program for foreign students.”

Ruth was careful not to talk about specific changes that he was contemplating. But he offered some thoughts about the direction he wants the program to take:

Summer Work Travel is under the State Department because it is supposed to be a cultural, educational experience for the participants. Work is its middle name. Work allows the participants to defray the costs of travel. That has always been seen as a worthwhile tradeoff, partly because it allows for large numbers to come, partly because it allows us to address a demographic that would not otherwise have the financial means to come to the United States.

A little later he added this:

I want to be sure that Summer Work Travel looks to you and me and any outsider like a genuine cultural experience. And to the extent that there are individuals who would seek to have it be something else or use it for another purpose, that is something I have to address through reforms, through rules, through clarifications of policy, to try to preserve the core intent of Summer Work Travel.

Young Thais Burnish Resumes with "Work Trah Vuhl"In the summer of 2011, when the Council for Educational Travel USA CETUSA) was barraged with criticism for placing SWT participants in strenuous jobs at a Hershey Co. warehouse in Pennsylvania, it defended itself by producing messages from placement agencies in Thailand clamoring for those very jobs. “We have good experience (at the Hershey plant) for couple of years and we expect to do well in recruiting appropriate students for them,” wrote a representative of Click Education, a student exchange agency whose motto is “Your Bright Future Is Our Goal.” At the same time, Click Education’s webpage was promoting a variety of SWT jobs for the spring of 2012. The offerings included work at McDonald’s restaurants in Alaska, New Mexico, Colorado, and New York; a supermarket in Las Vegas; and amusement parks in Kansas and St. Louis. Such work would be mundane to young Americans, but Click Education was selling American excitement. The webpage showed young Thais posing in New York’s Times Square, with background music was from American electro pop star Ke$ha, who sang: “Tick Tock on the clock, but the party don’t stop, no!” The popularity of SWT has surged in Thailand, where many ambitious university students regard a minimum wage job in the United States as a way to polish their resumes. Their American peers may think that an unpaid internship is the way to impress future employers, but Thais relish the chance to work in the United States, improve their English, demonstrate their ambition, and see some sights. “Most of us actually chose to work at McDonald’s,” Jiratchaya Intarakhumwong told the Global Post. “Employers will at least see that I could make it in America ... and that I’ve got some language skills.” The article said the program is “fueled by Bangkok’s upper-middle class families” who eagerly send their children on the program even though many take a financial loss.” “Thai students often describe their fast food tours of America in romantic terms, as a rite of passage and a rare opportunity to work and live among Americans,” Global Post reported. “Bookstores devote whole shelves to ‘work travel' guides,” and SWT has been taken into the Thai language as “work trah VUHL.” During their stint working at the McDonald’s inside Pittsburgh’s airport, Jiratchaya and her friends, described in the story as “students at some of Thailand’s most elite universities,” were earning the minimum wage and “bunked three-deep in a run-down Best Value Inn room.” The story described it as “an immigrant’s life.” But the experience apparently paid off for Jiratchaya, who returned home to find work as a service representative at the upscale Sofitel Hotel. Here are links to Thai SWT sites: http://www.thaiclickeducation.com/home/index.php http://www.kool-world.com/index.php http://www.acadexthailand.com/location.php http://www.awt.co.th/about-us.html And links to Youtube videos of Thai SWT participants: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WQQ_ofStCQs&feature=related http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aKtF6FL-FJg http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdCuzPorFgw

In September 2011 the smartworldasia.com website was recruiting Thai students as workers for a broad range of employers. It advertised openings at Six Flags Magic Mountain near Los Angeles; the Red Cliffs Lodge in Moab, Utah; the Econo Lodge in Wisconsin Dells; a Dunkin' Donuts in Mechanicsburg, Pa.; a Wendy’s in Thorndale, Pa.; a Dollar Tree retail store in Harrisburg, Pa.; a Quik Stop convenience store in Cherokee, N.C.; and a GAP store in Foley, Ala. The wages were all in the range of $7.25 to $8.25 per hour. There was also a night club in Detroit that was offering work at $2.65 an hour plus tips. In December the site was recruiting for a Vitality International retail store in Las Vegas; a Popsy Pop ice cream sales job in New Jersey; Publix supermarkets in Florida, South Carolina, and Alabama; and GAP stores in Alabama and Florida. |