Download a PDF of this report.

The Biden-Menendez immigration bill (U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021) would do three main things: Legalize virtually all illegal immigrants in the United States, weaken immigration enforcement, and double future legal immigration. To help inform the debate over this and other immigration proposals likely to be considered during this Congress, the Center for Immigration Studies has put together several presentations addressing various aspects of the bill’s three goals. They seek to provide background to the issues at stake, as well as likely consequences of any such legislation.

- "Prerequisites for Any Consideration of Amnesty", by Mark Krikorian

- "The Scope of the Amnesties Likely to Be Considered", by Mark Krikorian

- "The Current Illegal Population: How Did We Get Here?", by Andrew R. Arthur

- "The Operational Impact of Amnesty", by Robert Law

- "Chain Migration and Interior Enforcement", by Jessica Vaughan

- "Fiscal Implications of Amnesty", by Steven A. Camarota

- "Amnesty Would Cost the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds Hundreds of Billions of Dollars", by Jason Richwine

- "The Situation at the Border", by Todd Bensman

1. Prerequisites for Any Consideration of Amnesty

By Mark Krikorian

We might at some point have to consider amnestying some significant number of illegal aliens. This doesn't sit well with a lot of people, not even everyone at CIS.

BUT: The approach of the U.S. Citizenship Act, as well as the parts of it that House Democrats might pull out and try to move separately, all share two problems:

- There are no meaningful enforcement measures to try to limit the growth of a new illegal population after the current one is legalized.

- There's no legal-immigration offset, a reduction in numbers to counterbalance the increased green cards any amnesty would generate.

Enforcement

The Biden bill and any piecemeal spin-offs have no meaningful enforcement. But the solution is not to tack on some enforcement promises and call it a day. That was the approach of the 1986 amnesty and the amnesty bills that failed under Bush II and Obama — they were grand bargains of amnesty first, enforcement second. The 1986 promises of enforcement were not kept (they were lies from the start) and so no one believed the Kennedy-McCain or Gang of Eight promises would be kept.

The solution is Enforcement First. This does not mean setting enforcement benchmarks or triggers for already-legalized aliens to upgrade to green cards — the amnesty is over once the illegal alien is given a work permit (and Social Security number and a driver's license), so the oft-discussed "triggers" of prior amnesty debates are meaningless.

Instead, Enforcement First means full implementation of enforcement mechanisms necessary to limit future illegal immigration before any discussion of legalization. Specifically:

- Full roll-out of mandatory E-Verify;

- Entry-Exit tracking system at all ports of entry — air, sea, and land — up and running; and

- A federal prohibition against state and local sanctuary policies.

Legal Immigration Cuts

Any amnesty is, by definition, creating extra legal immigration, beyond the levels authorized previously by Congress. Therefore, it is incumbent on any amnesty proposal to, at the very least, offset the increase in immigration generated by the amnesty with a decrease in other categories going forward. Some categories ripe for elimination:

- Diversity Visa Lottery, 50,000/year

- Fourth Family Preference (siblings), 60,000/year

- Third Family Preference (married sons & daughters), 25,000

- First Family Preference (unmarried adult sons & daughters), 25,000

- First Employment Preference (investor visas), 10,000

There are others. The key point, though, is that this isn't just legislative horse-trading — cuts in future immigration are an integral part of any amnesty.

Miscellaneous

Certain illegal populations have developed for specific reasons and any measure to legalize or upgrade their status has to eliminate those causes.

- TPS. The reason we have close to half a million people in "Temporary" Protected Status, many of them here for two decades (as the Democrats constantly remind us) is that the executive can simply renew grants of TPS over and over, and the courts won't allow them to expire (as Trump discovered). So anything like the American Promise Act is incomplete — harmful, even — unless it either eliminates or fundamentally reforms TPS. Failing to do so just means more TPS grants as a means of amnestying illegal aliens in the future. American Prospect just published a piece in December calling for TPS for all illegal aliens from countries with Covid-19 (i.e., all illegal aliens). b.

- DACA/Dream. No upgrade for DACA beneficiaries can be permitted if it doesn't remove the incentives for adults to bring minors here illegally. Specifically, Flores and TVPRA need to be modified. These are seen as asylum loopholes, and they are, of course, but by incentivizing the illegal immigration of minors, they also help drive the "Dreamer" phenomenon of young illegal immigrants who have grown up here.

2. The Scope of the Amnesties Likely to Be Considered

By Mark Krikorian

The U.S. Citizenship Act is not going to become law.

Congressional Democrats and their advocacy groups know that. But the clock is ticking and they don’t want a replay of what happened under Obama, when no immigration legislation was passed.

The groups are still bitter over Obama’s decision in 2009 not to take advantage of Democratic control of Congress — including a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate — to pass anything on immigration. That decision put off immigration until Obama’s second term, by which time Republicans had taken back Congress — the end result being the failure of the Gang of Eight bill.

This time, the Democrats not only have razor-thin majorities, but they rightly fear that they’ll lose control of the House, at least, in next year's elections. They are desperate to get something passed; as Rep. Jimmy Gomez told Politico, "Whatever we do, we can’t walk away empty-handed."

That's why they’ve been open in expressing their willingness to move on "smaller" amnesty bills parallel to the comprehensive U.S. Citizenship Act.

The easiest way for them not to "walk away empty-handed" would be to simply re-pass bills that the House approved in the prior Congress, when Republican control of the Senate ensured they went no farther. But April 1 is the deadline to do that without time-consuming (and perhaps publicity-attracting) hearings and markups.

The details of such amnesty proposals are not unimportant, but the most consequential question is how many illegal aliens would potentially benefit from them. Below are estimates of the number of potential beneficiaries of the bills passed last Congress, and also the size of other subgroups of illegals who have been mentioned as possible beneficiaries of new amnesty legislation.

Total Illegal Population That Could Be Legalized

Pew, 2019: 10.5 million

Center for Migration Studies, 2018: 10.6 million

DHS, 2015: 12 million

FAIR, 2019: 14.3 million

Yale professor, 2021: 19.6 million

Scope of Possible Piecemeal Amnesties

Dream Act

CBO estimate: 2 million-plus

MPI estimate: 2.3 million

American Promise Act (TPS & DED)

CBO: "nearly half a million"

MPI: 429,000

Agricultural Worker Adjustment Act

MPI: 1.2 million

"Essential Workers"

MPI: 1.1 million to 5.6 million, depending on the meaning of “essential”

3. The Current Illegal Population: How Did We Get Here?

By Andrew R. Arthur

There are anywhere from 10.5 to 12 million aliens illegally present (and possibly more) in the United States today. That is up from approximately five million in October 1996. How did we get here?

Nonimmigrant Overstays, Illegal Entries, and a Decline in ICE Enforcement

- Nonimmigrant Overstays. In 2016, the Center for Migration Studies estimated that 62 percent of all illegal aliens in recent years had originally entered the United States legally as nonimmigrants, and overstayed their legal stay in the United States.

- In FY 2019, almost 56 million aliens entered the United States as temporary nonimmigrants.

- Nonimmigrants are supposed to return home at the end of their nonimmigrant admission periods, but that year DHS estimated that 1.21 percent (more than 676,000) remained longer than permitted.

- There are systems DHS uses to capture biometrics from aliens when they enter the United States, but although Congress has directed a biometric exit system be implemented for almost 25 years, that has not happened yet.

- So there is no way to ensure that nonimmigrants leave, and ICE lacks the resources to apprehend them unless they pose a national-security risk.

- In fact, in FY 2019, ICE removed just 7,469 aliens who were removable on immigration grounds alone (without criminal arrests or convictions) from the interior of the United States, a year in which there were 595,430 "fugitives" under final orders of removal who had failed to depart the United States.

- Illegal Entries. Hundreds of thousands of foreign nationals enter the United States illegally across our international borders or without proper documents at the ports of entry.

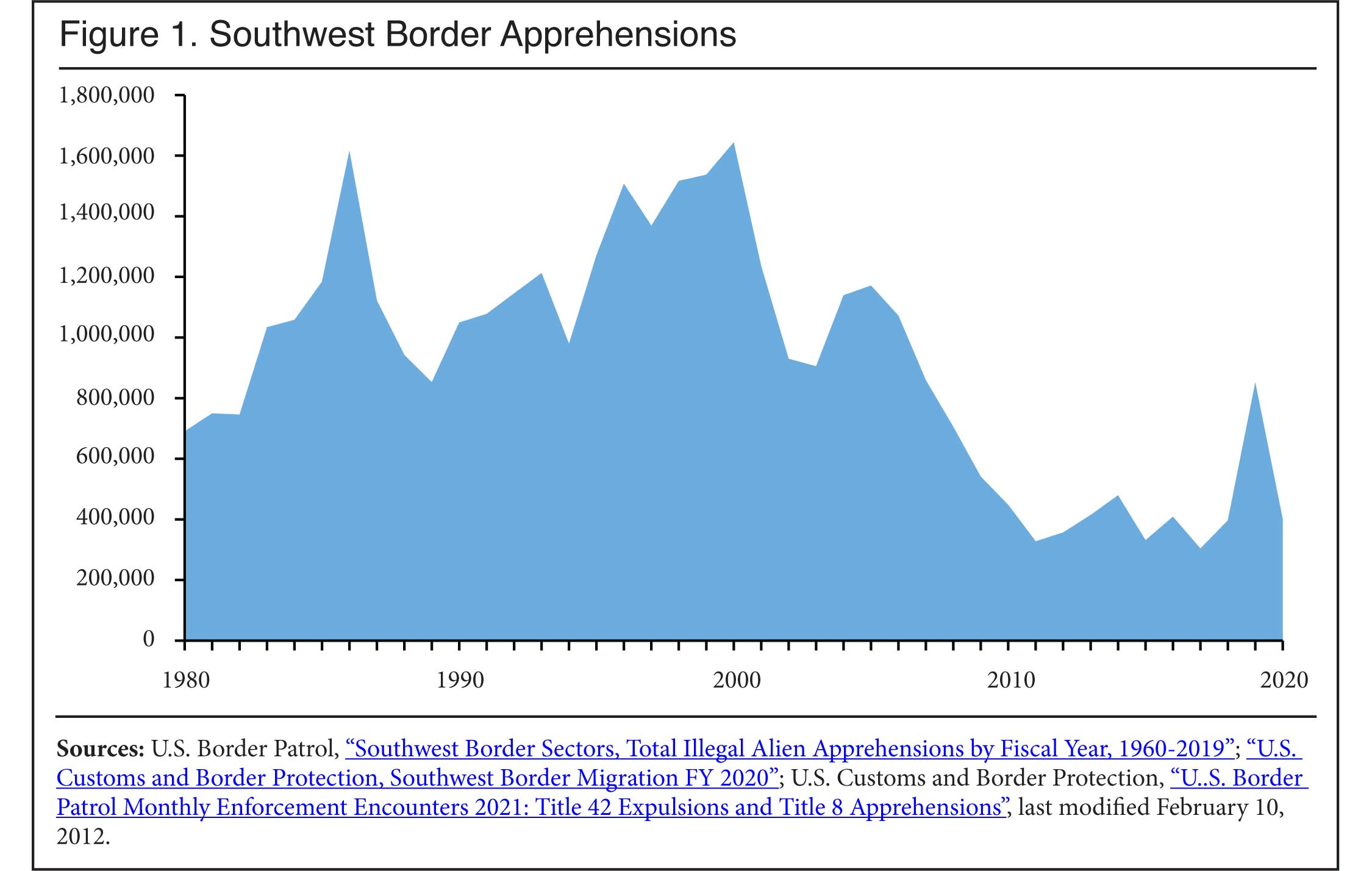

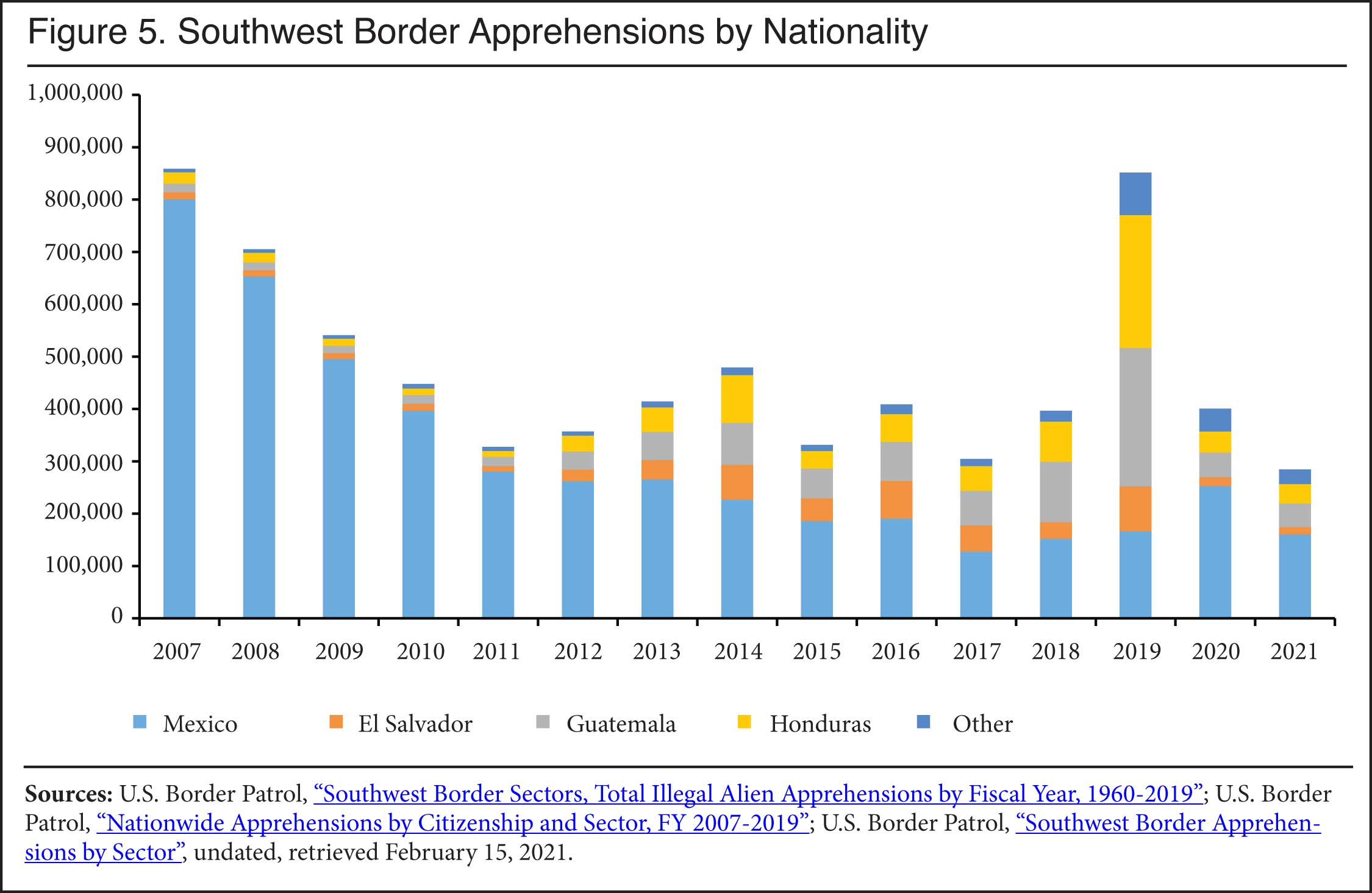

- In FY 1960, Border Patrol only apprehended about 22,000 aliens entering the United States illegally at the Southwest border. Beginning in FY 1974, that number exceeded half a million, and by 1983, topped a million, reaching 1.615 million in FY 1986.

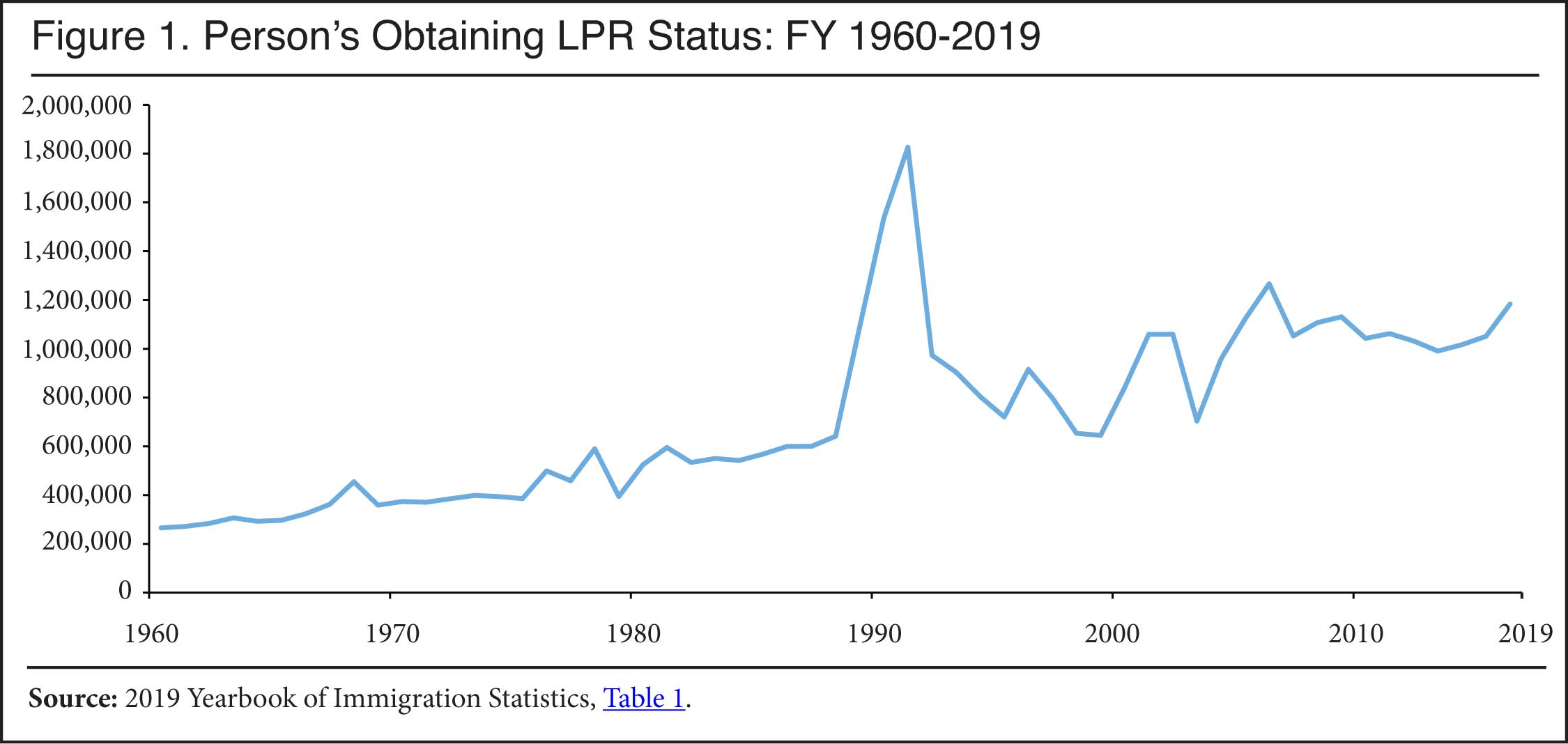

- In 1986, Congress enacted an amnesty that had legalized an estimated 2.7 million aliens illegally present in the United States by 2001.

- Border Patrol apprehensions of illegal aliens dropped below a million in FY 1988, but crept up again as aliens entered illegally in hopes of taking advantage of the next amnesty, reaching more than 1.643 million by FY 2000.

- The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, brought renewed focus — and resources — to the border, and apprehensions dropped below a million in FY 2002 and FY 2003, before exceeding a million in FY 2004 to 2006.

- Apprehensions then fell below a million (particularly following the "Great Recession" of FY 2008 and 2009, when the U.S. unemployment rate doubled) and have fluctuated since then from just over 300,000 in FY 2017 (most before Trump's inauguration) to more than 851,000 in the migrant crisis of FY 2019.

- Aliens who enter illegally along the border or without proper documents at the ports of entry are subject, under section 235(b) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) to "expedited removal", meaning that CBP officers can remove them from the United States without placing them in removal proceedings before an immigration judge.

- In FY 2019, between the border and the ports, CBP "encountered" almost one million aliens who would have been subject to expedited removal at the Southwest border alone.

- Mexican nationals can simply be returned back across the border, but due to loopholes in the law, many non-Mexican nationals ("other than Mexicans" or OTMs) — and many Mexicans, as well — are simply released into the United States for removal proceedings that can take four to five years to complete.

- During that period, they can live and work in the United States legally, and even if they are removed, ICE lacks the resources (as shown above) to pick them up.

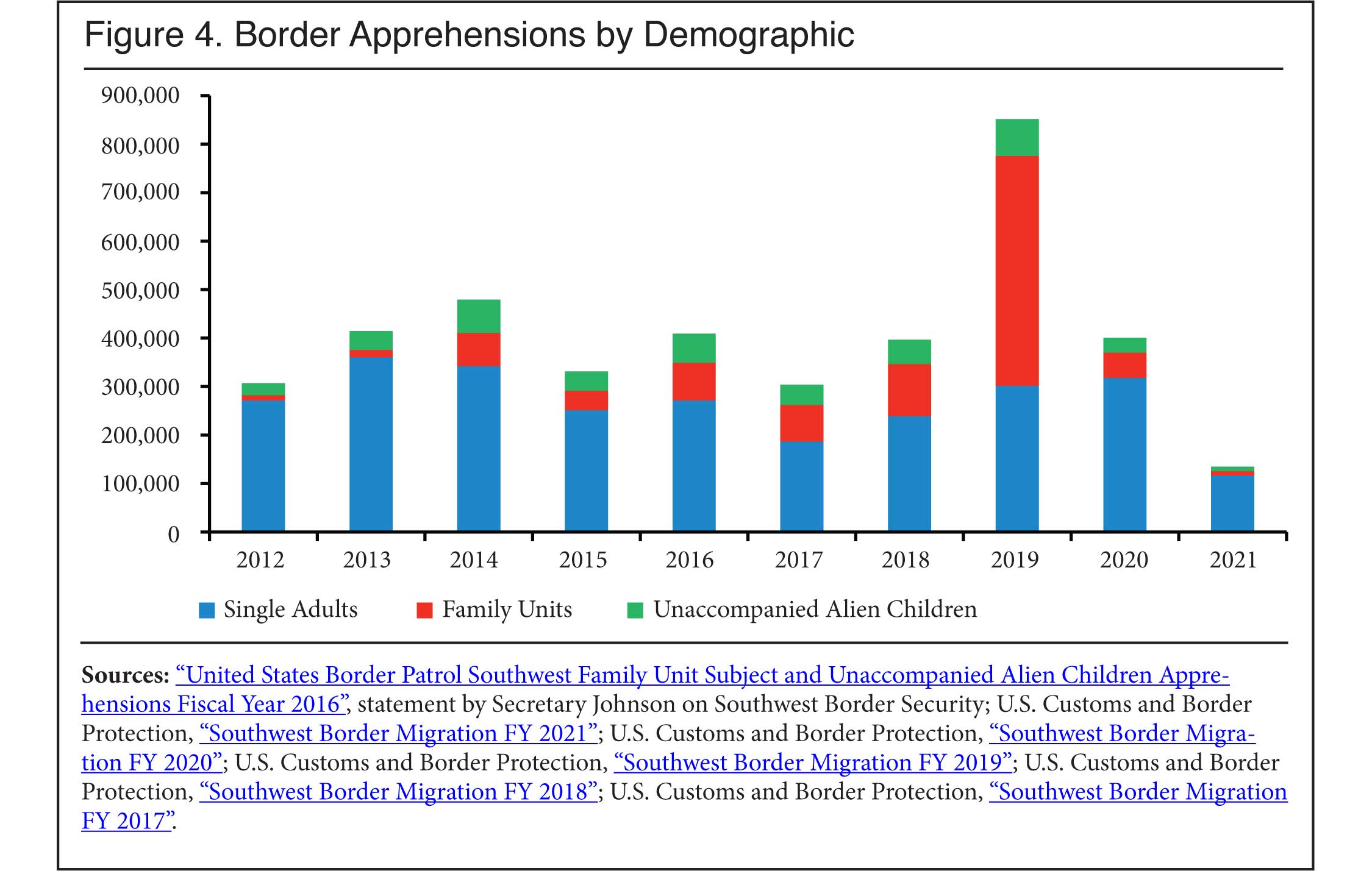

- Before 2011, 90 percent of illegal entrants were single adult males, and 90 percent were Mexican nationals. By FY 2019, only 35.4 percent of illegal entrants were single adults, and fewer than 20 percent were from Mexico.

- OTMs take much longer than Mexican nationals to process: on average, 78.5 hours for OTMs as opposed to eight hours for Mexicans. Border Patrol, however, lacks the facilities to hold large numbers of aliens — and in particular adults travelling with children ("family units" or FMUs) for an extended period of time.

- For that reason, when a large number of OTMs and FMUs are apprehended, Border Patrol will often issue them a "Notice to Appear" (NTA, the charging document in removal proceedings), and simply release them instead of processing them for expedited removal. That has occurred this month along parts of the Southwest border, and simply encourages additional illegal entries.

|

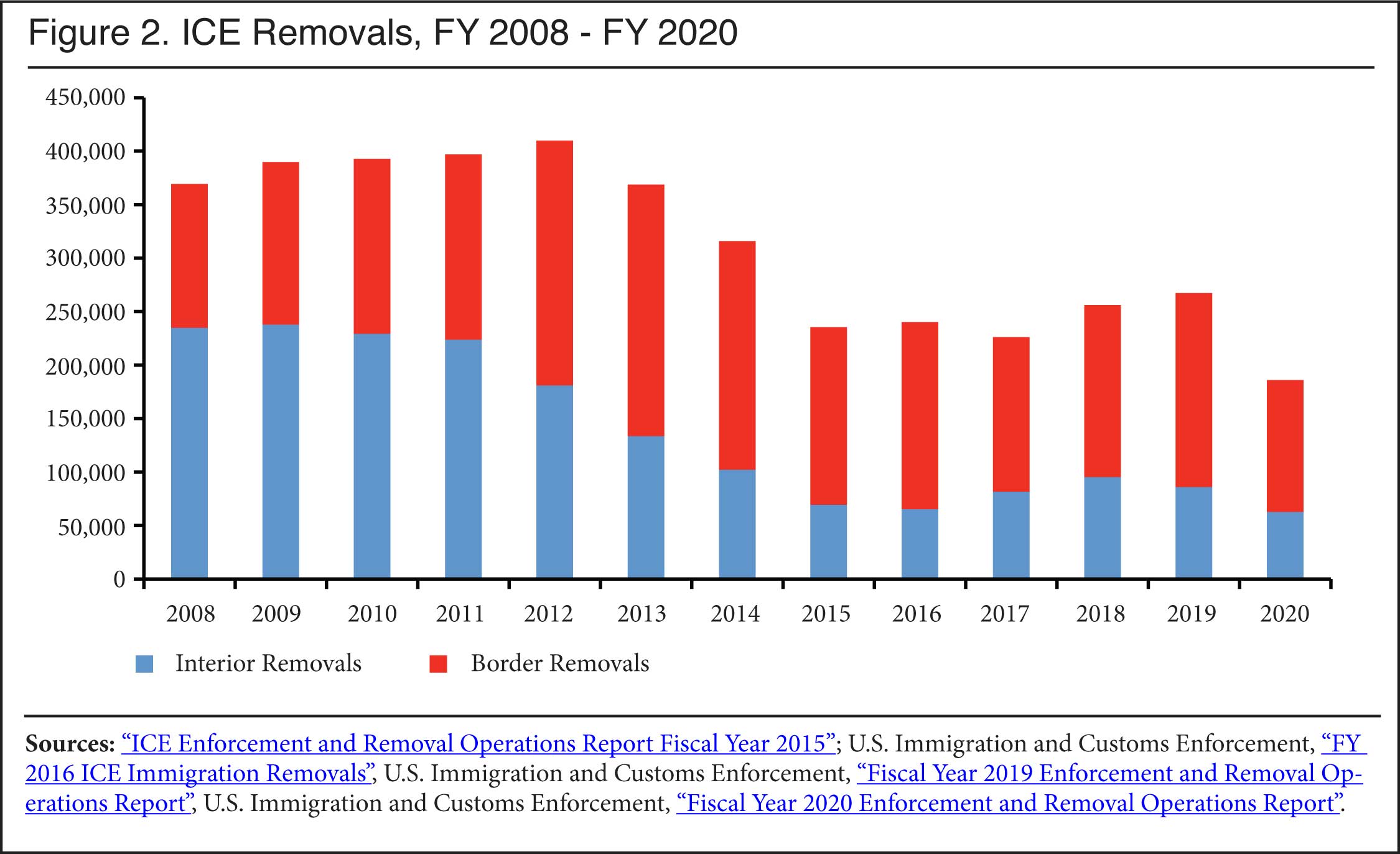

- Decline in ICE Interior Enforcement. ICE removals of removable aliens in the interior of the United States have been on the decline since FY 2012.

- Although so-called "interior removals" (as opposed to removal of aliens apprehended at the border) ticked up slightly during the first three fiscal years of the Trump administration, they never returned to the levels that they were at under the Obama administration in FY 2014.

- That FY 2014 number itself actually reflected a decline in interior enforcement that began in FY 2010, the first full fiscal year of the Obama administration.

- Throughout most of its history, there were no restrictions on the ability of ICE agents and officers (and agents from the agency's predecessor, INS) to arrest, detain, prosecute, and deport removable aliens, particularly criminals.

- That changed, however, in March 2011, when then-ICE Director John Morton issued the "Morton memo". Morton contended that ICE only had resources to remove 400,000 aliens annually, and so it had to "prioritize" its immigration-enforcement efforts.

- Pursuant to that memo, aliens who posed a danger to the national security, recent entrants, those convicted of aggravated felonies, and most criminal aliens were priorities for removal, but that memo did not prevent ICE from arresting or deporting other removable aliens.

- Nonetheless, in the fiscal year (FY 2012) after the Morton memo was issued, total ICE removals fell 23 percent, and ICE interior removals of aliens unlawfully present in the United States declined by more than 43 percent.

- In November 2014, DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson rescinded the Morton memo, and instituted his own priorities memo.

- As in the Morton memo, aliens posing a danger to the national security, recent entrants, criminal aliens, and aliens ordered removed on or after January 1, 2014, were identified as priorities in the Johnson memo.

- Under the Johnson memo, ICE could still arrest aliens who were not "priorities", if agents and officers received field-level supervisory approval.

- The Johnson memo drastically affected immigration enforcement, however. ICE interior removals fell an additional 32 percent the fiscal year that memo was issued (FY 2015), and in the next fiscal year (FY 2016), total removals dropped to 201,020 — just more than half of the 400,000 removals Morton claimed ICE had the resources to accomplish.

- Trump issued an executive order (EO) rescinding the Johnson memo on January 25, 2017.

- That EO prioritized the removal of aliens removable under the criminal, national security, expedited removal, and fraud grounds of inadmissibility and deportability; who had committed, been charged with, or convicted of crimes; and who had abused public benefit programs.

- ICE officers could arrest, detain, and remove other aliens who were not priorities without prior approval under that EO, but while the agency's interior arrests and removals rose slightly after that EO was issued, they never came close to reaching their FY 2014 levels.

- Fewer aliens removable solely on immigration grounds (that is, who did not have a criminal conviction) were arrested by ICE on an annual basis under Trump than under the any of the first five fiscal years of the Obama administration, before the issuance of the Johnson memo.

- Between FY 2017 and FY 2020, ICE removed just 935,346 aliens, 65 percent of whom had criminal arrests or convictions. Most of the remaining 35 percent of non-criminal removals occurred at the border, and in every fiscal year under the Trump administration, more than 89 percent of interior removals involved aliens with criminal convictions or facing criminal charges.

- At its peak under the Trump administration in FY 2018, ICE agents removed 95,360 aliens from the interior of the United States — 91 percent of whom had criminal arrests (14,114 or 15 percent) or convictions (72,627, or 76 percent).

- In FY 2014, by comparison, ICE removed 102,224 aliens from the interior, 85 percent of whom (86,923) had criminal convictions.

- By the end of FY 2019, there were 595,430 "fugitives" — that is aliens who had failed to leave the country after a final order of removal, deportation, or exclusion, or who had failed to report to ICE after receiving notice to do so — in the United States. That year, ICE arrested just 2,560 fugitives (.42 percent of the year-end total).

- The decline in interior removals under the Trump administration was not for lack of effort.

- Sanctuary jurisdictions restricted access to criminal detainees and/or access to information about those detainees.

- In addition, a large number of jurisdictions declined to honor ICE detainers — requests to hold a criminal alien who would have otherwise been released from state or local custody. In FY 2018, ICE issued 177,147 detainers, and in FY 2019 it issued 165,487.

- That year, the agency explained that it had "experienced an increase in the number of jurisdictions that do not cooperate with its enforcement efforts nationwide", and estimated "that limited visibility into the actions of state and local law enforcement in non-cooperating jurisdictions has also impacted the number of detainers issued."

- The pandemic in FY 2020 sent interior removal numbers (62,739) lower than even the Obama FY 2016 levels (65,322).

|

Loopholes That Encourage Illegal Entry

As noted, there are many loopholes in U.S. law that encourage aliens to enter the United States illegally. The three most significant ones are flaws in the "credible fear" system (by which aliens in expedited removal who claim a fear of return are screened for asylum claims), laws that govern the detention and release of unaccompanied alien children (UACs, alien minors under the age of 18 who enter illegally without an adult), and recent interpretations of the Flores settlement agreement.

- Deficiencies in the Credible Fear System.

- As noted, aliens caught entering the United States illegally are supposed to be "expeditiously removed" from the United States, without seeing an immigration judge.

- If the alien claims that he or she will be harmed if returned home, however, the alien will be interviewed by an asylum officer (AO) at USCIS for to see whether the alien has a "credible fear" of return.

- Where the AO finds the alien has established a credible fear, the alien is placed into removal proceedings to apply for asylum. If the AO finds no credible fear, the alien can ask for a review of that decision by an immigration judge (IJ).

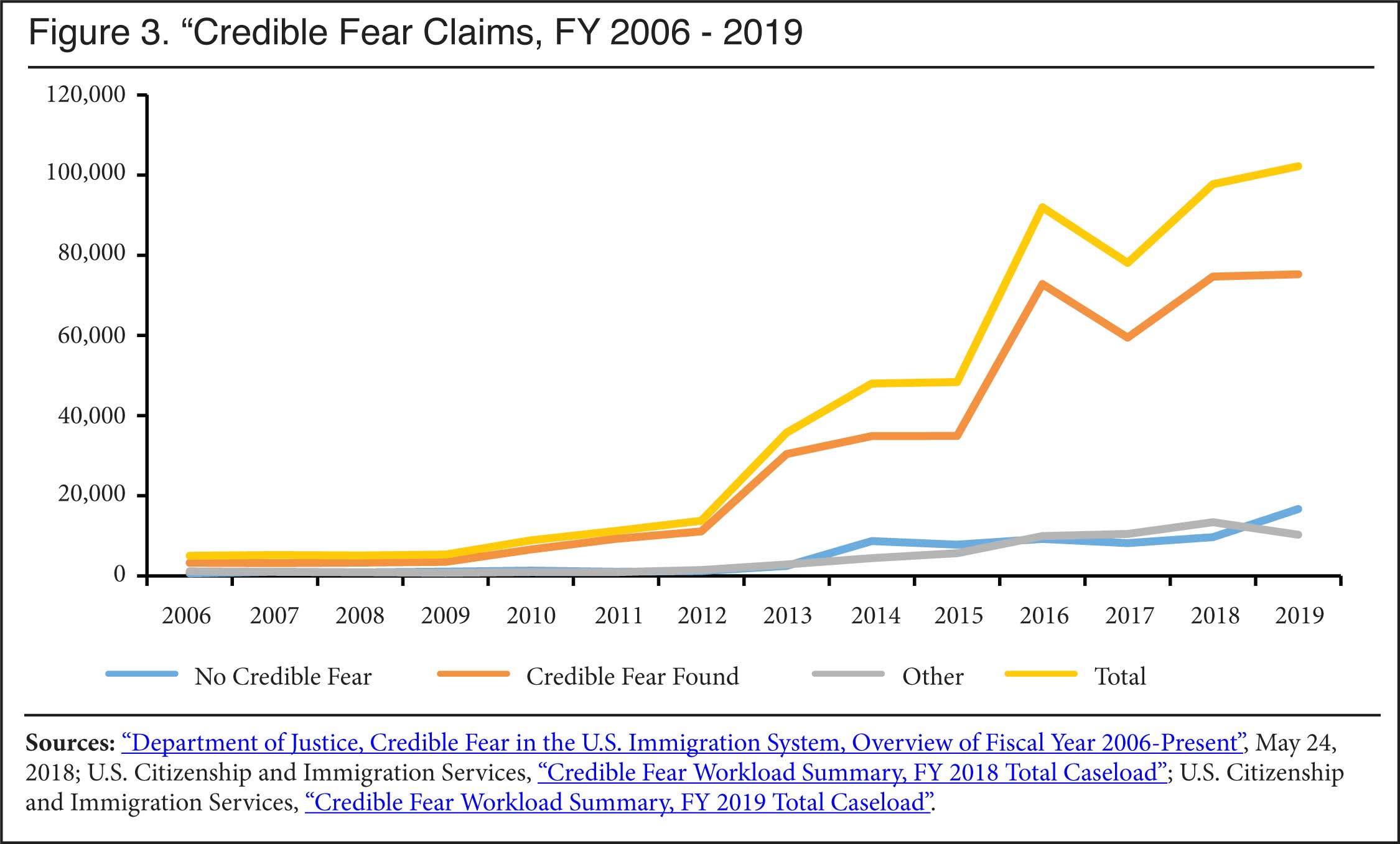

- Between FY 2008 and FY 2019, credible fear was found in about 83 percent of all cases of aliens in expedited removal proceedings who claimed a fear of return by AOs and immigration judges (IJs).

- In 2010, the Obama administration began releasing aliens found to have credible fear on "humanitarian parole".

- As a result, the number of aliens claiming credible fear increased significantly, from 5,325 in FY 2009, to 11,219 in FY 2011, reaching 105,439 in FY 2019.

- Although 83 percent of aliens who claimed they would be harmed between FY 2008 and FY 2019 were found to have credible fear, only 54 percent of those found to have a credible fear ever filed an asylum claim, and just 17 percent were eventually granted asylum. In fact, 32.5 percent of those aliens were ordered removed in absentia when they failed to appear in court.

- The statutory "credible fear" standard is too low, and the process has been abused by aliens with weak or fraudulent asylum claims, or no claims at all.

|

- The Current Iteration of the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA).

- Section 462 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (HSA) vested jurisdiction over the care and placement of UACs who are apprehended by DHS with the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

- That was amended by the TVPRA, which distinguishes UACs from "contiguous" countries (Canada and Mexico) from aliens who are nationals of "non-contiguous" countries (OTMs).

- A UAC from a contiguous country can be returned if the alien has not been trafficked and does not have a credible fear.

- Under the TVPRA, however, all OTM UACs are to be transferred to the care and custody of ORR within 72 hours and placed in formal removal proceedings, even if they have not been "trafficked".

- According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), in the second quarter of FY 2019, UACs spent about 47 days on average in ORR shelters.

- Between July 2018 and January 2019, 23,445 UACs were released to sponsors. Of those sponsors, 18,459 — 78.7 percent — had no status in the United States. Worse, 21 of the sponsors were under final orders from removal, six had been denied asylum and were appealing to federal court, and 638 (2.72 percent) were in removal proceedings.

- Section 462 of the HSA and the TVPRA encourage older UACs to enter illegally, and alien adults illegally present in the United States to pay smugglers to have their children brought to the United States.

- That trip results in significant trauma and a risk of harm to the UACs, and the parents and guardians almost always escape punishment, as Judge Andrew Hanen of the U.S. District Court of the Southern District of Texas noted in December 2013. He complained that DHS was turning "a blind eye to criminal conduct", and "participat[ing] in and complet[ing] the mission of a criminal conspiracy."

- The Flores Settlement Agreement (FSA).

- The FSA was originally signed in 1997 by the Clinton administration, to govern the standards of care and release of UACs in then-INS (now ICE) custody.

- In July 2016, the Ninth Circuit issued an opinion interpreting the FSA, which sustained an August 2015 order by a district-court judge. Both held that the FSA applied to alien minors in FMUs as well as UACs. Those courts also created a rule that all alien minors should generally be released by DHS within 20 days.

- The adults in those FMUs are generally released within 20 days, as well, to avoid "family separation".

- As a consequence, the number of adult foreign nationals — and in particular OTMs — entering the United States with children in FMUs has surged since those orders were issued. In FY 2014, 68,445 aliens in FMUs were apprehended by Border Patrol at the Southwest border. By FY 2019, that number swelled to 473,682 (an almost 600 percent increase) — 91 percent of whom were from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

- Many if not most of the FMUs apprehended in FY 2019 were released with just an NTA, because CBP lacked the resources to care for them.

- A bipartisan federal panel said that this practice was the major "pull factor" encouraging adults to bring children with them when entering illegally, exacerbated by the Ninth Circuit's decision in Flores. That panel called on Congress to "fix" the FSA by making clear that it did not apply to children in FMUs.

- That panel noted that the trip to the United States results in significant trauma to the migrant children, which could be avoided if their parents did not bring them along.

- In addition, in 2017, the NGO "Doctors Without Borders" reported that more than two-thirds of the migrants it surveyed were victims of violence during their transit toward the United States, and almost a third of female migrants had been sexually abused.

|

|

4. The Operational Impact of Amnesty

By Robert Law

Immigration Vetting: What Is the Government Looking For?

According to the Biden-Menendez mass amnesty bill, illegal aliens will have to pass "national security and background checks" as part of the eligibility requirements for legalization. To be clear, this certainly does not mean that the illegal alien has a clean criminal record or that derogatory information revealed by these checks will prevent all ineligible or inadmissible applicants from obtaining amnesty. In fact, an alien could be inadmissible on a criminal ground but still "pass" a background check. Presently, the Department of Homeland Security lacks a uniform definition of "background checks" and the mass amnesty bill would not fix this problem. As USCIS flagged in the Biometrics rule that the Biden administration has reportedly killed, the vagueness surrounding DHS's approach to background checks injects substantial vulnerability into vetting. Additionally, USCIS has historically not referred fraud findings very frequently and, despite the predictability of fraudulent amnesty applications, there is no reason to expect this practice to change under the Biden administration. Generally, there are three different types of background checks that USCIS runs, with each yielding different types of information.

- Fingerprint to FBI: IDENT is the automated biometrics identification system used to check biometric identifiers (i.e., fingerprints/photographs) against other databases. Because USCIS is not considered a criminal justice agency, the information that USCIS receives from the FBI is either incomplete or inadequate compared to what is provided to ICE and CBP. As a result, for immigration benefits the FBI is merely running a cursory search that is the equivalent of the background check run on an applicant seeking a job at a fast food restaurant.

- FBI Name Check: Currently, USCIS only uses this form of vetting for seven or eight benefit types. Even if used for the mass amnesty, the investigative check is based on the name and date of birth provided by the applicant or petitioner. This "honor system" structure is inherently vulnerable to exploitation as the check does not search for all variations of the applicant's name and date of birth.

- TECS (Treasury Enforcement Communications System): Unlike the FBI name check, TECS runs biographical information (name/DOB) and includes all aliases and prior names. TECS checks for warrants and the "no fly" list, but this form of vetting is largely not criminal in nature. While generally focused on fraud and national security, the downside is TECS can produce a lot of false positive results that take time for adjudicators to sort through.

Implementation Impact on Adjudications: Substantial Burden on USCIS Resources and Delays for Adjudicating Lawful Immigration Benefits

A mass amnesty program will substantially impact USCIS operations and will disrupt adjudications of lawful immigration benefits if the legislation fails to account for this impact.

Because USCIS is primarily fee-funded, the agency will require hundreds of millions of dollars in up-front resources to implement the amnesty because the fee revenue from the amnesty will not be realized until the program is fully implemented. (In 2018, USCIS estimated it would require $320-$400 million in upfront funding to properly implement an amnesty based on the DREAM and SUCCEED Acts. The Biden administration's rhetoric suggests that the amnesty they are contemplating is far more expansive, which could drive the upfront funding needs toward $1 billion.)

- Specifically, USCIS will need time and upfront funding to hire and train additional staff, expand contractor operations, expand or purchase new facilities, and acquire equipment necessary to implement the amnesty.

- USCIS will also need between 12-18 months to establish the amnesty program, including developing forms that capture sufficient information to ensure that only eligible illegal aliens obtain the amnesty.

Failure to provide adequate upfront funding will force USCIS to spend down its reserves, which, given the agency's financial problems due to Covid-19, are likely not enough to cover the costs and could bankrupt the agency. Additionally, USCIS already has some of its highest backlogs in recent history, so the amnesty work stream will further delay adjudication times for lawful immigration benefits, such as spousal green cards and employment-based nonimmigrant and immigrant petitions. Importantly, USCIS will only be able to recoup the full costs of processing the amnesty if the fees are set at true cost-recovery, instead of some arbitrary fee-level set by Congress in the bill.

5. Chain Migration and Interior Enforcement

By Jessica Vaughan

Chain Migration

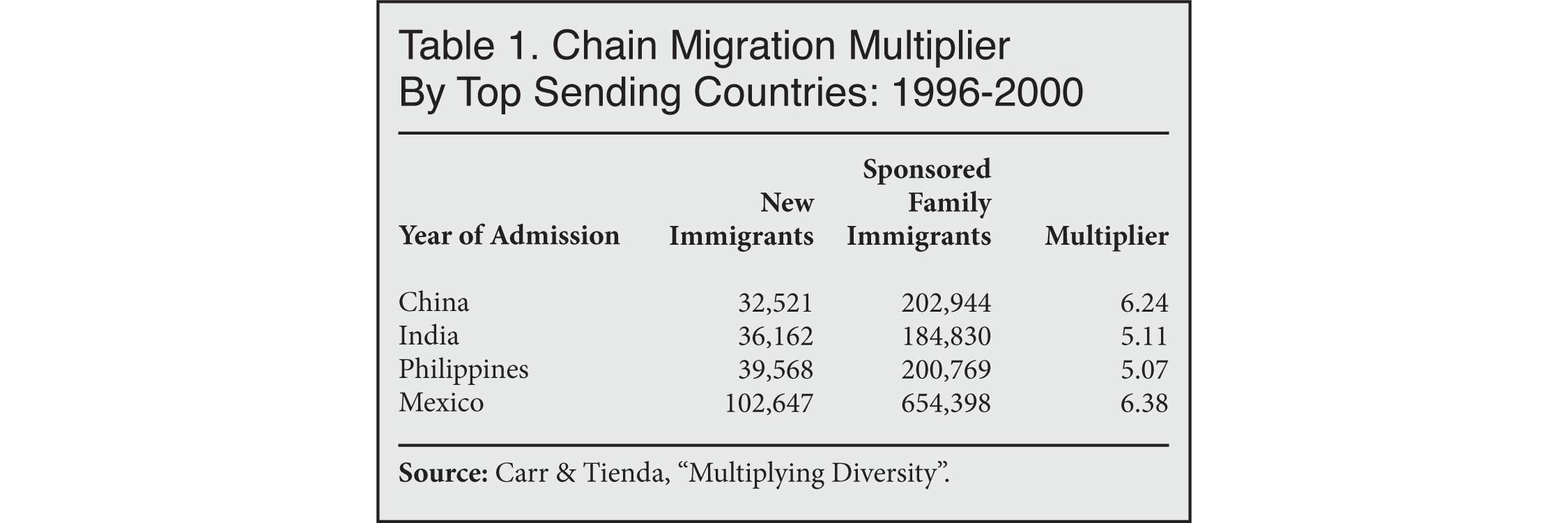

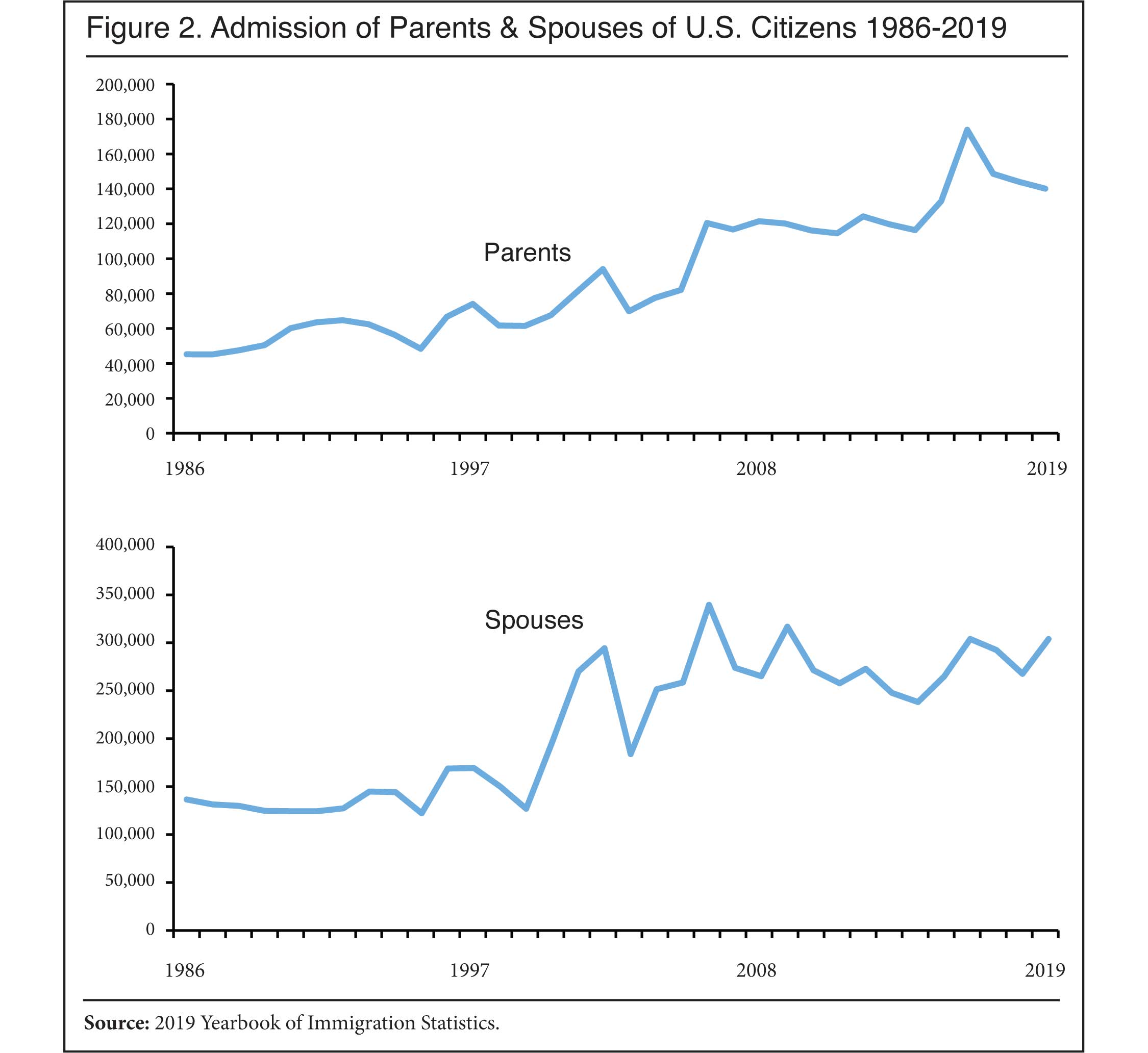

- Historically, amnesties have caused noticeable spikes in chain migration.

- The chain migration multiplier is 3.5 (i.e. the average new immigrant results in 3.5 immigrants).

- Chain migration is driven primarily by the unlimited admission categories of new spouses of immigrants, their children, and parents of U.S. citizens.

- The Biden bill will set off an avalanche of chain migration due to the amnesty, acceleration of the entry of those on the waiting list, increased admissions in existing categories, and the addition of new categories of immigrants.

Interior Enforcement

- The Biden bill includes no provisions to improve immigration enforcement, such as E-Verify, addressing sanctuaries, expanding entry-exit, etc.

- Biden's plan, as expressed by his appointees, is essentially abolishing immigration enforcement by prohibiting nearly all arrests and removals, building bureaucratic obstacles to enforcement actions, diverting resources away from enforcement, dismantling ICE's enforcement infrastructure (including eliminating the position of deportation officer), and offering services for deportable aliens.

- Currently ICE is limited to arresting and removing "aggravated felons", terrorists, and gang members. Protected criminal or illegal aliens include: prior deportees, absconders, overstays, and those convicted of "lesser" crimes, such as: DUI, assault, most sex crimes, identity theft, domestic violence, and property crimes.

- Worksite enforcement is not a priority.

- Besides creating public safety problems, these priorities send the message that anyone who succeeds in getting into the U.S. will be able to stay indefinitely without threat of removal. Further, those here illegally will have no incentive to return home on their own.

- The dismantling of enforcement creates an urgent need for oversight from Congress and vigilance on appropriations.

|

|

|

6. Fiscal Implications of Amnesty

By Steven A. Camarota

The proposed amnesty, which is likely to be called the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, includes the Dream and Promise Acts, which were passed by the House in 2019.1 The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that the net fiscal costs — new revenue minus new costs — of these bills in the first 10 years would be $34.6 billion at the federal level.2 Since the proposed amnesty is about four times larger than the Dream and Promise acts, the fiscal drain in the first 10 years at the federal level is almost certainly going to be more than $100 billion. This figure does not include any costs at the state and local level or include any costs after 10 years. It also does not include previously deported illegal immigrants allowed to return or increases in legal immigration.

There are five main reasons why an amnesty creates more new costs then new revenue. First, CBO, working with the Joint Center for Taxation, found that while taxes collected from illegal immigrants whose income would now be reported would increase, that "is offset by tax deductions by businesses for labor compensation." In other words, amnesty would reduce the taxes business pay by allowing them to deduct the wages they had previously paid illegal immigrants off the books, thereby mostly erasing the higher tax contributions of illegal immigrants whose wages would now be subject to taxation. Second, CBO estimates show that cash payments from the EITC and ACTC, which the legalized would now receive, would increase significantly. Third, CBO estimated a larger share of the children of illegal immigrants (particularly the U.S.-born) who are already eligible for means-tested programs such as SSI and Medicaid, would now be enrolled because their parents would no longer fear deportation. Fourth, amnesty would allow some of those legalized (Dream Act, Promise Act, and Agricultural Workers Adjustment Act recipients) immediate access to Obamacare subsidies. Those covered by the general provisions of the amnesty would not be immediately eligible for the subsidies, but would be after five years when they can adjust to lawful permanent resident status. Fifth, a very large share of illegal immigrants have modest levels of education, resulting in modest incomes and relatively lower tax payments regardless of legal status.

Amnesty in the Middle of Massive Job Losses

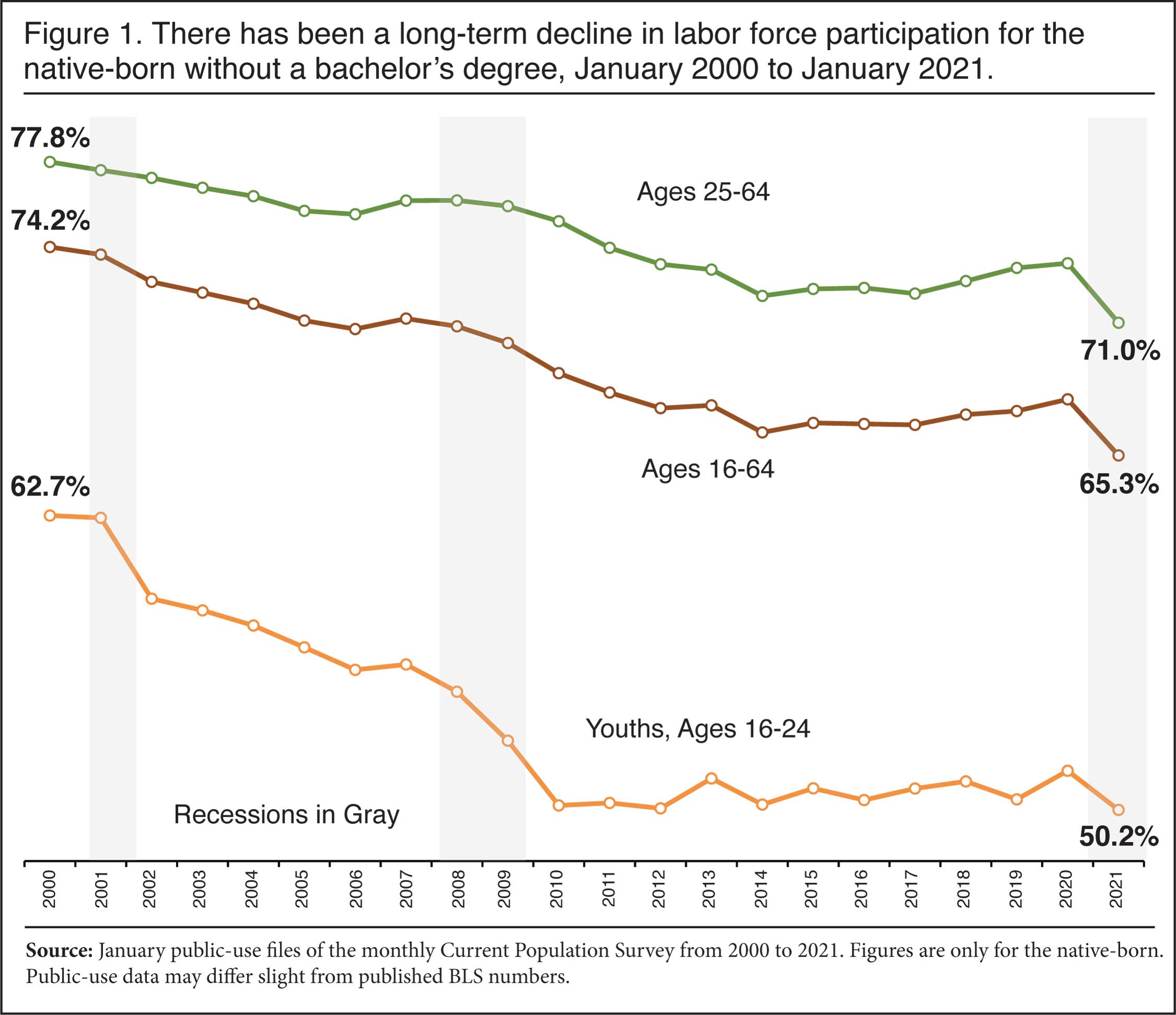

While the employment situation has improved some in recent months, the situation in January 2021 remained bleak. There were 10.9 million unemployed in January 2021, 4.3 million more than in January 2020 — before Covid-19.3 In addition, another 56.6 million working-age (16-64) residents are not in the labor force — neither working nor looking for work. Excluding young people, there were still 39.1 million people ages 25 to 64 who were not in the labor force.4 A total of 67.5 million were not working in January 2021. Of those not working, three-fourths don't have a college degree.5 Compared to January 2020, nearly eight million more people are unemployed or out of the labor force. All of this is happening in the context of a long-term decline in labor force participation for the less-educated. Those not in the labor force do not show up in unemployment statistics because the official unemployment numbers only reflect those who have looked for a job in the prior four weeks. There is a significant body of research showing a link between non-work and negative social outcomes such as crime, drug use, and family breakup. Allowing illegal immigrants to stay, and giving them all legal status so they compete with legal immigrants and the native-born throughout the labor market and significantly increasing legal immigration will make it more difficult to draw more Americans back into the world of work.

|

Notes

1 Letters from the Congressional Budget Office to Chairman Nadler, May 30, 2019, regarding the Dream Act of 2019 (H.R. 2820) and the Promise Act of 2019 (H.R. 2821).

2 Ibid.

3 "The Employment Situation — January 2021", Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), February 5, 2021. BLS reports both seasonally adjusted and unadjusted figures, see Table A-1. The seasonally adjusted number unemployed was 10.1 million, compared to 10.9 million seasonally unadjusted. In January 2020, the number unemployed seasonally adjusted was 5.8 million and it was 6.5 million unadjusted. The difference is 4.3 million January to January, comparing adjusted to adjusted or unadjusted to unadjusted.

4 Center for Immigration Studies analysis of January 2021 public-use file of the Current Population Survey (CPS). This figure is seasonally unadjusted. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has not fully disclosed its seasonally adjustment methodology during the Covid-19 pandemic; moreover BLS does not generally publish labor force participation data for those 16 to 64. Our figure is based on the raw data, which is available to researchers to download and analyze.

5 Center for Immigration Studies analysis of the January 2021 public-use file of the Current Population survey, seasonally unadjusted. Figures are based on unemployment among persons without a bachelor's degree ages 25 and older; labor participation is based on persons 25 to 64. If those younger than 25 were included the share would be higher.

7. Amnesty Would Cost the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds Hundreds of Billions of Dollars

By Jason Richwine

Although illegal immigration flouts the rule of law and strains local communities, it does generate one unambiguous benefit — namely, free contributions to our Social Security and Medicare trust funds. Amnesty would transform those contributions into costs totaling hundreds of billions of dollars.

The reasoning here is simple. Under current law, most illegal immigrants cannot access Social Security or Medicare benefits even when they reach retirement age. Nevertheless, roughly half of illegal immigrants do have payroll taxes deducted from their wages while they are working. These payroll tax contributions are generally "free" to American taxpayers because they bolster the trust funds without creating any new benefit obligations. However, amnesty would qualify recipients for Social Security and Medicare, converting future contributions into large IOUs from the federal government.

The cost difference between the status quo and amnesty is large by any measure. Consider the following back-of-the-envelope calculation. Based on our analysis of the American Community Survey, the average working-age illegal immigrant is 39 years old and earns $28,500 annually. Let's say that amnesty boosts his wages by 10 percent immediately; that he receives additional yearly increases of 1.2 percent based on official projections of wage growth minus inflation; and that he works until the full retirement age of 67. If so, he would collect about $18,640 in annual Social Security benefits. If his lifespan is statistically average, he will collect this annual benefit until he dies at the age of 80. To understand the magnitude of these future benefits, we need to "discount" the benefit stream, meaning consolidate it into a single upfront cost. Applying a discount rate of 2 percent, the present value of his total lifetime benefits comes to $140,330.

This average illegal immigrant will also pay 12.4 percent of his wages (the sum of the employer and employee contributions) to the Social Security trust fund. Applying the same assumptions listed above, the present value of his taxes paid after amnesty would be only $94,500, which by itself creates a deficit. But remember — roughly half of illegal immigrants already contribute payroll taxes even without amnesty. In other words, the new taxes paid by the average amnesty recipient amount to only half of the $94,500 noted above. The net effect of amnesty is therefore $140,330 - $47,250, which is about $93,000 per recipient. In any large-scale amnesty, in which millions of illegal immigrants gain legal status, it is easy to see how the net cost could reach into the hundreds of billions of dollars.

This is just a rough estimate. We are currently working on a detailed model that will provide more precise costs for both Social Security and Medicare. Again, however, any reasonable calculation will produce a large cost, simply because amnesty will convert so many outside contributors into actual beneficiaries.

Please note that the costs described here are driven by amnesty itself, not by immigration in general. Whether bringing more immigrants into the U.S. burdens entitlement programs is a complicated question that hinges on issues of fertility and long-term growth. In the context of amnesty vs. the status quo, however, the immigrants are already here — the only issue is whether we will decide to pay them Social Security and Medicare benefits that they otherwise would not receive.

Unfortunately, the Congressional Budget Office usually projects budgetary impacts only 10 years into the future, meaning it will not capture most of the Social Security and Medicare costs associated with amnesty. Costs falling outside of the 10-year budget window are no less real, however. Lawmakers need to be aware of the full, long-term costs of any amnesty legislation that comes up for debate, and those costs will inevitably include hundreds of billions of dollars charged to the Social Security and Medicare trust funds.

8. The Situation at the Border

By Todd Bensman

- Migrants throughout the Americas see Biden administration messaging and policy as a flashing green light that they can enter the United States without obstruction and will not be detained or deported. CIS believes all of this has set up a probable mass migration event at the border, as Biden policy fuels high enthusiasm and travel plans throughout Latin America and the world.

- In its first weeks, Biden policy impacts were widely inconsistent, but the administration saw that it could use the Title 42 quick-expulsion policy from the Trump administration to dampen an imminent mass migration event.

Shortly after the inauguration, Title 42 was oddly suspended in the Del Rio, Laredo, and Rio Grande sectors, but only in those few sectors, resulting in the first catch-and-release practice since the last mass-migration crisis in 2019. Thousands of Haitians, Cubans, and Central Americans, usually in family units, were led straight to Greyhound bus stations in these sectors. None were tested for Covid-19. The onslaught only stopped within a day or so of New York Times and Washington Post reports about what was happening, and Title 42 was re-imposed. No public explanation was given.

- The new Biden border management processes are highly vulnerable to crashing amid overwhelming numbers of migrants now massing in northern Mexico and crossing, fueled and emboldened by the earlier catch-and-releases and promises of amnesty and the end of deportations and detentions.

- Credible reports have migrants from throughout Mexico and beyond traveling to northern Mexico border cities to take part in the entrance free-for-all, despite the Biden administration's unexpected reliance on Title 42 expulsion authorities

- There were reports in mid-February by Guatemala of the latest caravan forming in Honduras, but caravans may not materialize as a contributor to overwhelming mass migration because the Biden administration has pressured local governments to stop them.

The Biden administration apparently has pressured Guatemala and Mexico to use its militarized police forces to break up migrant caravans as a means to deflect political damage to the Biden immigration agenda. Both Guatemala and Mexico have agreed to continue Trump-era policies of forcibly breaking up the caravans. Therefore, it seems likely that the new caravan will not advance far. Also, Mexico apparently has no plan to redeploy the 20,000 national guard troops it felt obliged to deploy on its southern and northern borders when Trump demanded this.

- Extra-continental migrants and special interest aliens will come in increasing numbers soon, presenting a national security threat issue.

A significant build-up of migrants behind pandemic-related border closures further south in Panama and Costa Rica involves migrants from countries of the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa, as well as China, India, and from sub-Saharan Africa. There have been significant civil disturbances among them. Panama is now transporting thousands of them to Costa Rica, which likely will move them to Nicaragua. We anticipate that these migrant populations soon will find their way to the U.S. southern border, presenting a national security threat of terrorism.