USCIS has issued a self-congratulatory “Fiscal Year 2022 Progress Report” in which it seems to regard denying Americans jobs in the American economy as progress.

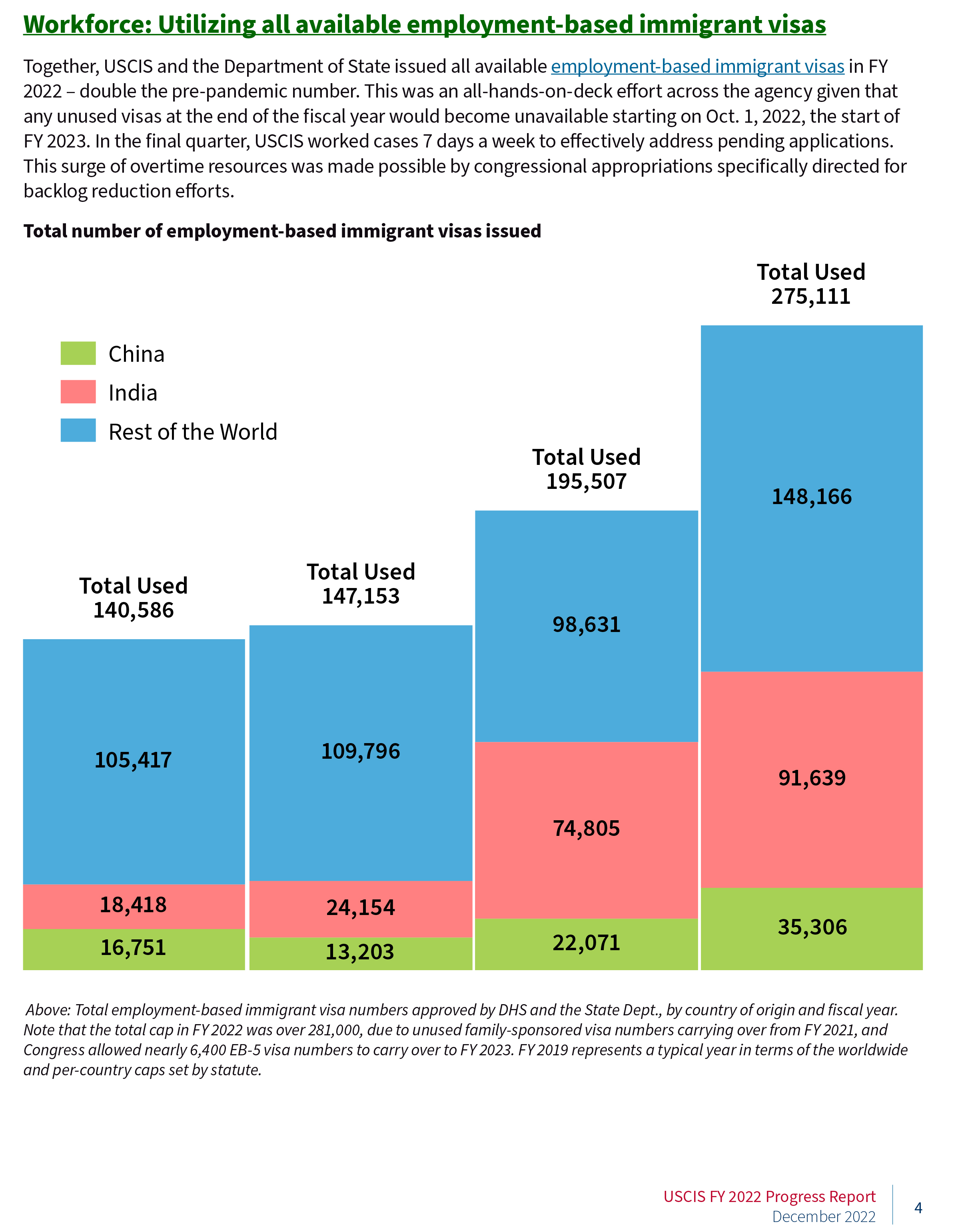

For example, it happily (and sloppily) announced that it and the State Department — in an “all hands on deck effort” — had issued double the pre-pandemic number of employment-based immigrant visas in FY 2022, going from 140,586 of them to 275,111. The figure, on page 4 of the report:

|

The reader will note that there are four columns on the page; these are not identified in the report, a major omission, but probably represent admissions in this category during FYs 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022. (The careful reader will also notice that the number of EB aliens from India rose by close to five-fold in this unstated time period; these are mostly ex-H-1Bs and their dependents.) The rise came about because of the use of previously unused visa slots.

We move on to page 7 of the report where we see the agency bragging that “USCIS is making available more supplemental H-2B nonagricultural worker visas than ever before.” This time the figure makers, while identifying the years involved, engage in a bit of graphic manipulation to make the increases appear more significant (and in my eyes more damaging) than they really are. Here is the figure:

|

What the figure shows is the additional supplemental H-2B workers, not the total number of such workers (as was shown on page 4), leaving out the routine allocation of 66,000 a year; this makes the agency’s decision-making seem to be more dramatic than it really was.

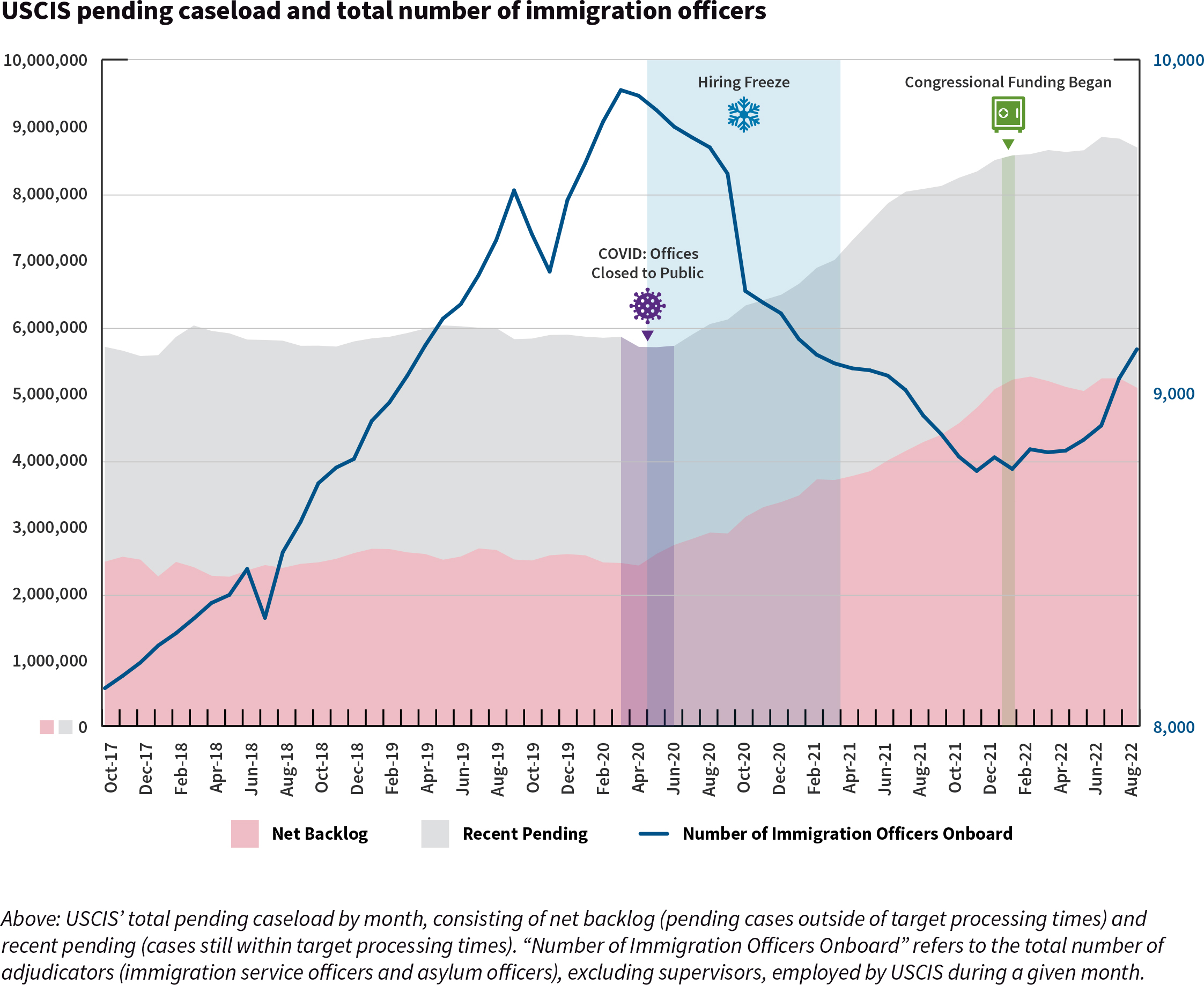

My favorite mal-presentation in the report comes on page 13 and deals with the growth of backlogs of USCIS applications of all kinds, but first a comment on the social utility of these non-decisions. While the agency regards the reduction of such backlogs as progress, I have a more nuanced view of them — while generally government ought to make decisions when such are called for, and people should not to have to wait for years for them, the non-making of some nine million of them by USCIS cannot be doing anything but slowing international migration, and that’s a good (if not planned) thing.

Not all pending decisions relate to swelling our population; they fall into three categories. Some change the status of an alien who is already here (such as naturalization); some (TPS, for example) give legal status to those illegally here; and some cause the admission of new people. But given the record of USCIS of rubber-stamping some 85 percent to 90 percent of the papers before it, ending the nine million backlog would certainly expand our population by a million or two; America is over-stuffed with people already.

That backlog figure on p. 13 is titled “USCIS pending caseload and total number of immigration officers”:

|

As one looks at the graphic, for the period April 2020 to August 2022, one sees that the number of USCIS decision-makers has fallen from nearly 10,000 to a little over 9,000, while the backlog of un-decided applications has grown from a bit under six million to about nine million — hardly an indication of progress from the agency’s (or the aliens’) point of view.

Yet reading the burbling text we find: “[T]he dedicated workforce of USCIS is turning the tide on its pending caseload.”

BTW, throughout this report — as one might expect — there never is a single mention of the fact that many citizens and green card holders are not working because of the presence of large and growing numbers of alien competitors in the labor market.