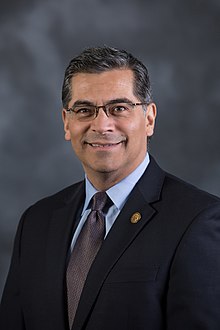

A recent Politico article was captioned “Border fiasco spurs a blame game inside Biden world”. It focused on complaints about Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Xavier Becerra’s handling of the unprecedented number of unaccompanied alien children (UACs) recently apprehended at the Southwest border. Becerra is only partially to blame: He’s the wrong man, and HHS is the wrong agency, to deal with the migrant crisis.

By way of background, when DHS was created in the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (HSA), that bill was amended by House Democrats to give the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in HHS jurisdiction over the unaccompanied children that DHS apprehended.

That role was expanded in the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA). As I explained in my last post, the TVPRA divided UACs based on nationality, with Mexican and Canadian children on the one hand, and children of all other nationalities on the other.

DHS can quickly return Mexican and Canadian children home if they have no fear of return and have not been trafficked.

All other children, however, are to be sent to HHS (within 72 hours, when possible), for placement in shelters HHS runs or contracts for. Those children, in almost all cases, are to be placed with sponsors in the United States — most (about 60 percent) of whom are their own parents here illegally — and are placed into removal proceedings (which can drag out for years).

The Washington Post asserted in August 2014 that the TVPRA “has encouraged thousands of Central American children to try to reach the United States by granting them access to immigration courts that Mexican kids don’t enjoy”, and President Obama called, unsuccessfully, on Congress in June 2014 to plug this loophole.

As I noted on April 14, HHS has 7,700 beds in its permanent shelter network (at a cost of $290 per child per day). When it has to hold more children than that, HHS must scramble for space (which runs around $775 per child per day). Recent complaints have focused on the department’s ability to do so in a timely, safe, and humane manner.

While the Border Patrol apprehended more UACs in March than any other month for which the component keeps records (back to 2010 — UAC apprehensions were not a significant issue until after the TVPRA was passed), this is hardly the first UAC surge.

the Border Patrol apprehended more than 36,000 UACs between March and June 2014, and almost 36,700 between March and June 2019 (there were smaller surges in between). Every time a surge occurs, HHS struggles to deal with the issue, and whichever administration is in office gets blamed (although Donald Trump was particularly excoriated).

Biden-friendly outlets have cut the president some slack on this issue. The New Yorker, for example, ran an article headlined “Biden has Few Good Options for the Unaccompanied Children at the Border”, which stated “the Trump Administration was plainly acting in bad faith” when it opened “influx facilities” to handle UACs in 2019.

Why “bad faith”? Because that article conflated “family separation” under the administration’s April to June 2018 “zero tolerance” policy (pursuant to which all adult illegal migrants — parents included — were to be prosecuted for illegal entry) during the unaccompanied child surge in the spring of 2019.

Time reported in October 2020 that 5,400 children in total were affected by the family separation policy, including 1,000 after it was ended in June 2018. Some of those separations occurred because parents had criminal records — a few of which according to the ACLU were minor — and some because the familial relationship could not be established.

All of that said, such family separations did occur on a smaller scale under the Obama administration (it reportedly didn’t keep numbers on how many children were affected), and according to the Washington Post, Trump’s announcement of the end of family separations “was something smugglers quickly seized on. They began telling would-be clients that children were a passport into the United States.”

That surge in adults entering illegally with children led to its own problems (and for those children, serious risks and trauma), as detailed by a bipartisan federal panel in April 2019, but more importantly, while family separation (even when it was in full swing) may have exacerbated HHS’s inability to house UACs under the Trump administration, it certainly didn’t cause it.

Remember, HHS has shelter space for 7,700 unaccompanied children, but almost 11,500 were apprehended by Border Patrol at the Southwest border in May 2019 alone.

Here’s the real problem: Providing shelter for an unknown number of unaccompanied children is always going to be a tricky task, but almost two decades after it was first given the job, HHS is still not very good at it, and for good reasons, as Politico explains.

An unnamed “senior administration official” quoted by the outlet talked about the problems faced by ORR in handling unaccompanied children and placing them with sponsors, explaining:

On every front they’re confronted with challenges that are more than a little bit outside their comfort zone. ... We’re trying to build a scaffolding around them to account for or mitigate some of their own gaps, because in some ways it’s just a completely different culture.

That “different culture” is reflected on ORR’s own website. On its “What We Do” page, that office explains:

The Office of Refugee Resettlement ... provides new populations with the opportunity to achieve their full potential in the United States. Our programs provide people in need with critical resources to assist them in becoming integrated members of American society.

Notice what’s missing from that description? Anything having to do with sheltering and placement of UACs.

That said, how after almost 20 years of handling UACs can ORR be “outside of [its] comfort zone” in performing a fairly key responsibility? The answer is clear: HHS is not really a law enforcement agency, and call housing UACs whatever you want, but at the end of the day, it’s really just detention.

In other words, ORR should never have been given the responsibility to begin with. ICE detains thousands of aliens every day — it has been one of its key functions since it took over that responsibility from the former Immigration and Naturalization Service. And, complaints notwithstanding, it does a pretty good job of it (and as a former immigration judge at a detained facility, I should know).

I was there the day that the aforementioned amendment to the HSA was offered and, at the time, I thought that it was a petty and spiteful slap at the INS (where I had served, among other positions, as associate general counsel). If ORR was lobbying for the job at the time, they likely have regrets now.

For the time being, however, it’s ORR’s — and therefore HHS’s — job. Consequently, it should have been incumbent on the Biden administration to have picked someone with experience to head that department.

Secretary Becerra, however, was almost definitely the wrong person for the job. There are more than 80,000 employees at HHS, and the department’s agencies range from the (currently omnipresent) CDC to the Indian Health Service to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (ORR is actually just an office within HHS’s Office of the Administration for Children and Families).

Becerra, a former member of Congress (1993 to 2017), California assemblyman (1990 to 1992), and California state attorney general (2017 to 2021), though, is not a health expert — he’s a lawyer, albeit one with a respectable academic pedigree (with a B.A. and J.D. from Stanford University).

Even if he were a health expert, however, the largest organization that Becerra has ever supervised was the California Office of the Attorney General, which has “more than 4,500 lawyers, investigators, sworn peace officers, and other employees”. Needless to say, the duties of the California state AG’s office are significantly more focused than HHS’s are.

This is not the first time that I have seen a political appointee in over his head. There is an anecdote that one former INS director was given his choice between that job and postmaster general, and chose the former because “the Post Office is a mess” (INS did not exactly run like a Swiss watch, and his tenure did not improve matters).

Nor is this the first time that I have seen the UAC issue come to define HHS’s performance. A fellow staff director when I worked for Congress had responsibility for oversight of the department. He expected he would be handling Obamacare and drug pricing, only to be faced with a prior surge of unaccompanied children, and attendant complaints about their housing and release.

All of this can be avoided. In my last post, for example, I called on Congress and the administration to rethink the discrimination in the TVPRA between Canadian/Mexican UACs and all other UACs, because that section of the TVPRA was a mistake with serious — if “inadvertent” — consequences (and given the fact that President Obama and the Washington Post agreed with me, I was almost definitely correct).

Congress and the president should also rethink the decision in the HSA to give ORR responsibility for unaccompanied children. This almost 20-year experiment has been a failure, so shut it down, now.