Download a pdf of this Backgrounder.

Jessica M. Vaughan is the Director of Policy Studies at the Center for Immigration Studies. CIS Fellow James R. Edwards, Jr., PhD, is coauthor of The Congressional Politics of Immigration Reform.

Shortly after midnight on September 9, 2001, Maryland state trooper Joseph Catalano pulled over a red Mitsubishi rental car traveling 90 mph in a 65 mph zone on I-95 north of Baltimore. The driver, Ziad Jarrah, had a Florida driver’s license and quietly accepted the $270 fine issued by Catalano before continuing on to join his friends at a hotel in New Jersey. Two days later, Jarrah boarded United Airlines flight 93, which he would later pilot into a field near Shanksville, Pa., killing everyone aboard.

In 2001, Trooper Catalano had no way of knowing that Jarrah was an illegal alien who had overstayed his business visitor visa. But in the years since 9/11, dozens of state and local law enforcement agencies have been able to join ranks with federal immigration authorities under the auspices of the 287(g) program to help identify and remove foreign nationals who commit crimes or otherwise pose a threat to our well-being. These state and local agencies are making a significant contribution to public safety and homeland security, not just in their jurisdictions, but for us all.

Yet the Obama administration, in a move consistent with other recent steps to scale back immigration law enforcement, recently announced its intent to impose new rules for the 287(g) program that unduly constrain the local partners and could allow too many alien scofflaws identified by local agencies to remain here. But even with these changes, which seem to be based on unsubstantiated criticism from ethnic and civil liberties groups, the 287(g) program still remains an effective tool in immigration law enforcement and local crime-fighting. To ensure its continued success, Congress should provide additional funding and guidance to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), so that the program continues to meet the needs of local agency partners and the communities they protect.

This Backgrounder examines the 287(g) program’s history and its status. How is it being used? Which law enforcement agencies participate? What has the 287(g) program’s effect been on the foreign-born criminal element? We interviewed participating local law enforcement agencies (LEAs), reviewed statistics and reports provided by local LEAs, analyzed data provided by ICE through a FOIA request, and scoured news reports on the program. We begin by recounting briefly the program’s origin, then describe its application and results. We conclude by offering a number of recommendations. Between those bookends is the story of the 287(g) program’s successes, challenges, and potential.

Some of our findings:

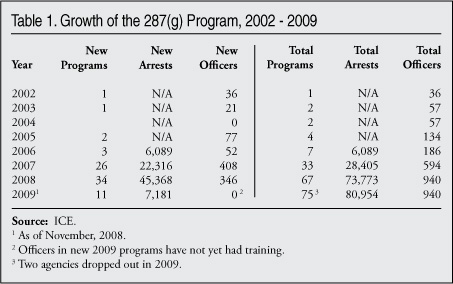

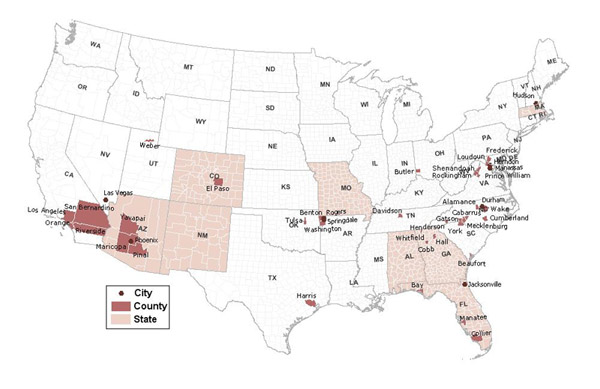

- About 1,000 officers from 67 law enforcement agencies have been trained and participate in the program. With 9 new agencies joining and a handful of agencies dropping out in 2009, the total number of participating agencies as of October 2009 is 73.

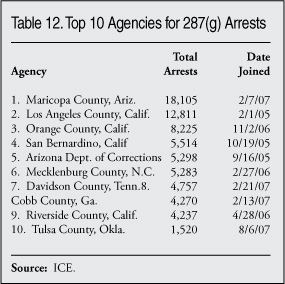

- 287(g) officers lodged immigration charges on more than 81,000 illegal or criminal aliens between January 2006 and November 2008, according to data provided to us by ICE.

- In 2008, the number of 287(g) arrests (45,368) was equal to one-fifth of all criminal aliens identified by ICE in prisons and jails nationwide that year (221,085). The program has flagged a large number of known serious and/or violent offenders, as well as some low-level offenders still at the bottom of the criminal behavior escalator. Illegal aliens targeted by the program have been identified as a result of involvement in local law-breaking in addition to immigration law-breaking.

- While 287(g) agencies use the authority mainly to identify and process illegal aliens who have committed additional crimes, Congress never intended the program to be limited to that use. Lawmakers intended for local agency partners to use the authority for local law enforcement priorities and according to local needs, which may or may not be the same as federal priorities.

- Participating agencies credit the 287(g) program as a major factor in reduced local crime rates, smaller inmate populations, and lower criminal justice costs.

- 287(g) is cost-effective — much less expensive than other criminal alien identification programs such as Secure Communities and Fugitive Operations. For example, in 2008 ICE spent $219 million to remove 34,000 fugitive aliens (mostly criminals). In 2008, ICE was given $40 million for 287(g), which produced more than 45,000 arrests of aliens who were involved in state and local crimes. In Harris County, Texas, the billion-dollar ICE Secure Communities interoperability program found about 1,718 removable aliens in its first six months beginning late in 2008; meanwhile the locally paid 287(g) officers in the same jail system charged about 5,000 criminal aliens over the same time period.

- 287(g) is a force multiplier. In 2008, the Colorado state 287(g) unit alone made 777 immigration arrests. In that same year the entire ICE investigations office based in Denver, which covers all of Colorado and several other states, made a total of 1,594 arrests. In Maricopa County, Ariz., the local ICE detention and removal manager supervises five ICE deportation agents, who are supplemented by 64 additional locally paid county jail 287(g) officers who also identify and process criminal aliens.

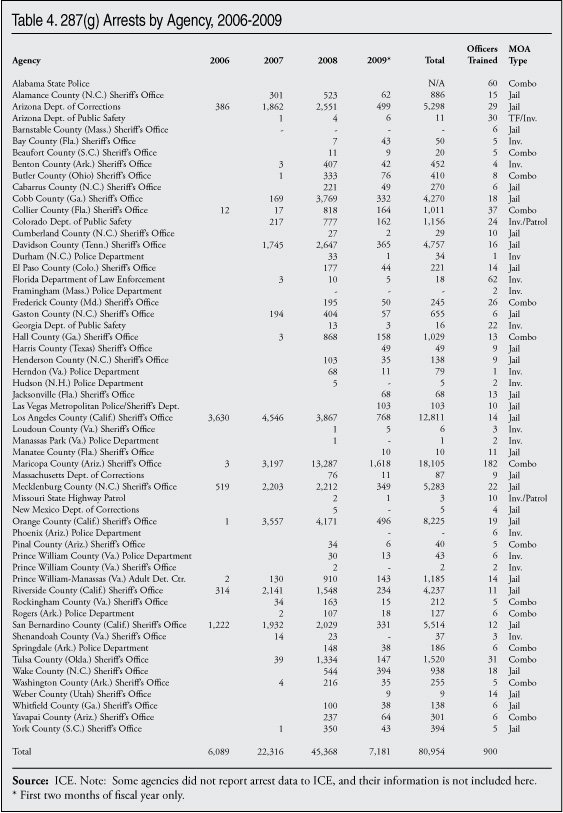

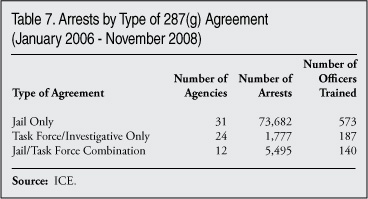

- The largest number of agreements have been signed for correctional 287(g) programs. These programs were responsible for 91 percent of the 287(g) arrests over the period we studied.

- The task force/investigative programs provide equally important crime-fighting benefits and are a useful tool to address such illegal immigration-related crime problems as alien smuggling, drugs, street gangs, and identity theft.

- The Colorado, Arizona, and Alabama 287(g) programs have boosted ICE efforts to combat alien smuggling, which has been neglected since the agency’s formation.

- Notwithstanding allegations from immigrant and civil liberties advocates, there have been no confirmed instances of racial profiling, discrimination, or other abuse of authority under the 287(g) program. There is no evidence whatsoever of a “chilling effect” on crime reporting in the 287(g) jurisdictions.

- The waiting list for 287(g) is long — reportedly one to three years from the time of request to join until implementation. A number of agencies have launched interim programs in cooperation with ICE that can put a significant dent in the criminal alien population while they are waiting. In Gwinnett County, Ga., such a preliminary surge screening operation of interviews at the jail in early 2009 resulted in deportation holds on nearly 1,000 criminal aliens in 26 days. Two-thirds had committed very serious and/or violent crimes, and the rest were arrested on lesser charges that time, although many had more serious prior offenses in their background.

- The biggest obstacle to improving and expanding the 287(g) program is the lack of funding for bed space to detain illegal aliens discovered by local agencies to have committed crimes. As a result, ICE currently is removing fewer than half of the criminal aliens identified under 287(g). Several states have submitted proposals to ICE to help alleviate this problem, but ICE has not acted to increase funding for bed space, even as it claims to prioritize the removal of criminal aliens.

287(g): Origins and Rationale

Section 133 of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) provided the then-Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) the authority to enter agreements initiated by state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies. Memoranda of agreement would enable local police to assist federal authorities in the investigation, arrest, detention, and transportation of illegal aliens and gain better cooperation from the INS in dealing with the burgeoning population of foreign nationals committing crimes. IIRIRA was enacted September 30, 1996.

California Congressman Chris Cox helped secure the inclusion of this measure in the broad immigration bill. The California Republican was sensitive to the pleas of local law enforcement, who were being overwhelmed by the number of illegal and criminal aliens causing problems in their jurisdictions; received too little response from the INS (which was understaffed, underfunded, and disorganized); and needed additional training, authority, and leverage to get the INS’s cooperation instead of a cold shoulder.

Iowa Senator Charles Grassley was a leading sponsor of the companion measure in the Senate. Grassley was motivated by the murder of an Iowa college student at the hands of illegal aliens, and frustrated by the fact that the INS has no agents in Iowa at the time.

The 287(g) program provides full-fledged immigration officer training to a set of local or state law enforcement officers. While state and local officers have inherent legal authority to make immigration arrests,1 287(g) provides additional enforcement authority to the selected officers such as the ability to charge illegal aliens with immigration violations, beginning the process of removal. Under the program, a law enforcement agency agrees to a number of its officers receiving intensive immigration enforcement training, supervision of 287(g) officers by federal agents for immigration enforcement duties, and is assured of federal immigration cooperation and coordination in certain immigration-related enforcement activities.

This measure was largely noncontroversial and unnoticed. Lobbies on all sides of the immigration issue mostly targeted other provisions, such as mandatory employee verification, or entirely parochial concerns. Even many members of Congress not as attuned to the immigration issue were naturally sympathetic to helping state and local law enforcement agencies.

Contrary to recent claims of some opponents, while the removal of criminal aliens was foremost in the minds of the congressional sponsors, 287(g) was never intended to be limited or focused solely on aliens who commit serious crimes. Rather, the legislation was intended to give local law enforcement agencies a tool to help compensate for the federal immigration agency’s limitations. Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), the bill’s chief House author, said recently at a hearing: “The goal was to really enable those local law enforcement authorities who wanted to enforce the immigration laws in whatever way they thought best, and that might or might not include those who have committed serious crimes. Some people ... are under the mistaken impression that somehow that’s required by the legislation, and that’s really a decision made by the government in individual situations.”2

There is no indication that Congress meant to give the federal government much discretion as to whether or not to enter a requested agreement. The initiators of agreements to participate in this new program were to be state and local agencies. Congress intended that the agreements be completed and implemented, not hamstrung or suffocated with red tape. And each agreement was to serve primarily the needs of the particular locality or state, not the preferences of ICE managers in Washington.

As IIRIRA began to be implemented, Section 287(g) (the new section of the Immigration and Nationality Act) was mostly idle. INS made no major efforts to publicize the new program. In 1998, encouraged by then-Attorney General Janet Reno and U.S. Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), Salt Lake City, Utah, police chief Ruben Ortega asked the city council to approve a plan to become the first agency to join the program. Ortega maintained that illegal aliens from Mexico were responsible for most of the city’s rampant drug trade, representing 80 percent of felony drug arrests in the city. The police department found it very difficult to arrange for the removal of criminal aliens, as the nearest INS offices were hundreds of miles away, in Reno and Denver. The city council narrowly rejected Ortega’s request in a 4-3 vote, siding with the ACLU and Hispanic activist groups who feared that the program would lead to civil rights violations against all Hispanics in the city and cause immigrants to refrain from reporting crimes. Another jurisdiction that reportedly had been considering joining 287(g), Alamance County, N.C., subsequently dropped the idea (although it did join later, in January 2007).

Only after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, did the Justice Department, where INS then resided, really get the 287(g) program going. Until then, political leaders in the most immigrant-heavy locales, such as Southern California and Florida, had resisted allowing their officers to become involved in this type of law enforcement.

However, the confluence of a “war footing” and unchecked immigration reaching more parts of the nation sparked interest in all options along the lines of the 287(g) program. The ensuing federal investigations, which revealed that a number of the terrorists had had contact with state and local law enforcement agencies — providing an opportunity to disrupt their plans — and the subsequent work of the 9/11 Commission highlighted vulnerabilities to national security, especially with regard to illegal immigration, identity fraud, and laxity in the visa system. Meanwhile, mass immigration at unprecedented levels led to increased presence of aliens farther and farther from the borders. The Ashcroft Justice Department viewed the 287(g) program as something beneficial in the fight against Islamic terrorism, as well as to rebuff the Latino gangs and smuggling rings that were pushing their illicit operations further and further inland.

Alabama and Florida led the way. In 2002, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement became the first agency to participate, initially training 35 officers to use their authority in homeland security-related investigations, later adding 23 more after seeing how well it worked. In 2003, Alabama’s Department of Public Safety enrolled 21 of its state troopers and driver’s license examiners, focusing on fraud at the Department of Motor Vehicles, and added another 35 officers shortly after. Increasingly since then, state and local law enforcement agencies have joined the program and many more have expressed interest or attempted to participate.

The need for cooperation between local LEAs and ICE is no less today. ICE has neither the resources nor the personnel to process the entire criminal alien population by itself. ICE has estimated that there are 300,000-450,000 foreign nationals incarcerated in the nation’s jails and prisons every year.3 The agency currently attempts to locate removable inmates in only about 10 percent of these institutions, and together with programs in place at state prisons, these efforts result in removing only a fraction of the incarcerated criminal alien population (221,085 were identified in 2008).4 Some sheriffs have estimated that a significant share of the inmates in their county jail system are illegal aliens. Maricopa County reports that 22 percent of felons sentenced are illegal aliens; in Lake County, Ill., 19 percent of jail inmates are illegal aliens; and in Weld County, Colo., 13-15 percent of jail bookings are illegal aliens.

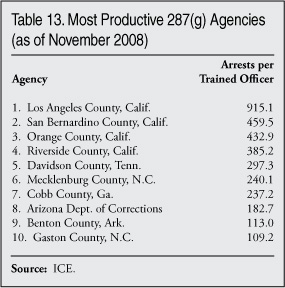

As of November 2008 there were 67 active 287(g) jurisdictions, and more than 950 officers had been trained and certified in immigration law enforcement. According to ICE documents we obtained in a FOIA request, these officers were responsible for identifying more than 81,000 removable aliens between January 2006 and November 2008.

Application Process

The process for participating in the 287(g) program is straightforward. A local or state law enforcement agency or government contacts the Department of Homeland Security’s Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), often via a form provided on the ICE website. The state or local agency requests an agreement under this program and the arrangement must be approved by an executive branch official of the local jurisdiction. According to the law that established the program, ICE is then supposed to begin designing a memorandum of agreement for the agency. The agreement, or MOA, details the scope of the authority, the number of officers to be trained, and the purposes the specific arrangement is to serve.5

As the program has become more well-known, the number of interested local agencies has grown faster than ICE says it can accommodate, and there is now a long list of agencies waiting to join. In addition, ICE has developed criteria that each jurisdiction must meet in order to be approved. Among other factors, it expects the agreement to be consistent with ICE mission priorities (e.g., ICE will not approve agreements aimed explicitly at addressing day-labor site problems or illegal employment;6 the jurisdiction must have adequate detention and inmate transport capabilities; and the jurisdiction must demonstrate that it has what ICE considers to be a severe criminal alien problem. The local ICE office must endorse the arrangement and confirm that it can support the partnership. Ultimately, ICE makes the call on whether a requesting agency may participate (contrary to congressional intent).

As part of the evaluation process, ICE often will conduct a “surge” operation in the jurisdiction to help determine the magnitude of the criminal alien problem in that area. This typically involves sending a team of immigration agents to screen the current jail population. Several jurisdictions that have hosted ICE surge operations report that large numbers of illegal aliens were identified and flagged for removal as a result. So in addition to quantifying the scale of the problem, the surge itself provides public safety and fiscal benefits.

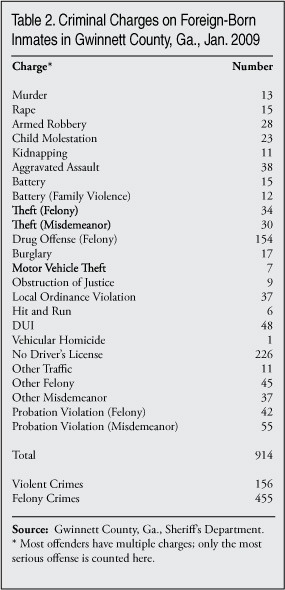

For example, Gwinnett County, Ga., received authorization to apply for 287(g) in April 2008. Total jail admissions for 2008 were 39,890, of whom 14,227 were foreign-born. In January 2009, ICE agents launched a 26-day surge operation. By the time it was over, they had charged 914 of the inmates with immigration violations on top of their local charges. These removable aliens represented 68 percent of the foreign-born inmates at the time.

Table 2 lists the offenses committed by these inmates (in addition to immigration violations). Two-thirds of the aliens identified in the ICE surge had committed serious crimes, i.e., crimes other than license, ordinance, minor traffic, or similar misdemeanors. More than half of the criminal aliens identified had previous criminal records, mostly in Gwinnett County.7

Other county sheriffs have released the results of their pre-287(g) surge operations, with similar findings. Lake County, Ill., just north of Chicago, reported that its one-day audit found that 19 percent of the inmates were illegal aliens, and that the suspects in half of the county’s 14 murders were illegal aliens. After the audit, Sheriff Mark Curran estimated that the county could receive up to $4 million a year in reimbursement payments from ICE for detaining removable aliens detected under the 287(g) program.8

The results of these audits, which reveal such large numbers of potentially removable aliens in jails, often surprise ICE managers who sometimes seem to have underestimated the scale of the local problems, according to local law enforcement agencies. Said one sheriff when describing his 287(g) negotiations with ICE: “You should have seen them [the ICE managers] sweating bullets when we told them how many illegal aliens we had in our jails.”

Training

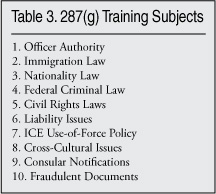

After a 287(g) MOA is signed, ICE arranges for an agreed-upon number of officers to attend the four-week training course taught by ICE instructors, which often takes place at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Georgia. The course covers immigration law, the removal process, documents and identification, consular notification, civil and human rights, avoiding racial profiling, counter-terrorism, other immigration-related public safety issues ,and ICE paperwork.

ICE was slow to develop the ability to manage the training program and clearly did not anticipate and plan for the strong demand from local agencies. Many local agencies have reported long delays in getting an acknowledgement or response to their request, and complain about “getting the runaround” in the negotiation process. The process, from inquiry to completing training and setting up the equipment, apparently takes one to three years — an eternity in almost any field other than immigration. While ICE made some progress in 2008 working through the backlog of requests, some of the agreements have been languishing for more than a year, often without a clear or logical explanation for the delay from ICE. For example, Gwinnett County’s program reportedly was delayed, ironically, because ICE said it had to hire a new agent to supervise the work of the future 287(g) officers, a step that seems curious for a program designed, at least in part, to help alleviate the need to hire more federal agents to identify criminal aliens.

Officers in 287(g) must be U.S. citizens, undergo a background investigation, have at least two years of experience in their positions, and be clear of any pending disciplinary actions. While remaining full-time employees of their home department, these officers also are “deputized” as federal immigration officers for operations under the 287(g) arrangement. Supervised by ICE agents, these officers may question individuals suspected of being unlawfully present in the United States, arrest and detain them until status is determined, and begin the removal process for illegal or criminal aliens.

ICE pays the training costs for 287(g) officers and reimburses travel expenses at the end of training. The state or local police agency pays the officers’ salary. Officers must assume up-front expenses for lodging and food at training, which are later reimbursed by ICE. Prior to the aforementioned revisions introduced by DHS Secretary Napolitano, ICE covered the costs of computers and other information technology necessary for gaining access to immigration databases. Now, ICE is asking the local partners to pay for this expense, although reportedly it is willing to waive this requirement on a case-by-case basis.

Types of 287(g) Programs

There are three basic types of 287(g) agreements: Correctional, Highway Patrol, and Task Force (or Investigative). Many agencies have combination Correctional-Investigative programs, which provide the greatest flexibility. See Table 4 for a list of the agencies and type of agreement.

Correctional

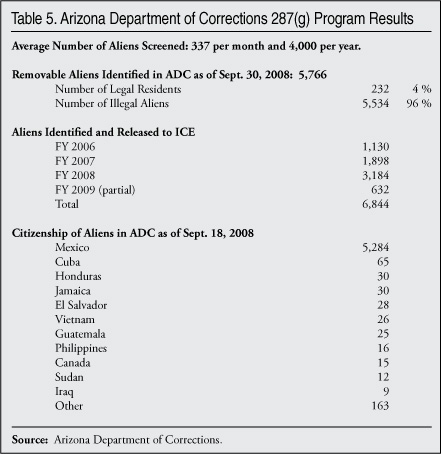

The most common use of the 287(g) program is in a correctional setting, usually a county jail system. Thirty-one out of the 67 agreements in place at this writing are strictly correctional agreements. Another 12 jurisdictions have agreements for the jail and for a task force or investigations. All but three of the correctional agreements are county jail operations. Three states (Arizona, New Mexico, and Massachusetts) have 287(g)-trained personnel working in the state prison system, although only the Arizona system produces a significant number of arrests (see Table 4).

ICE has stated that it prefers correctional agreements over other models, although this is not the model that was originally envisioned for the program. The rationale for a correctional 287(g) agreement is very compelling, for both policy and practical reasons. The enforcement activity is targeted at criminal aliens, who are always the highest priority and least controversial population to be subject to removal. The jails are a natural choke point for identifying aliens who have committed crimes. However, ICE does not have the staff to cover the thousands of county jails on a regular basis. Currently, through its Criminal Alien Program, ICE screens on a regular basis at only about 10 percent of the local jails, and even then the coverage is usually only during the day shifts.9 One problem is that the jail inmate population turns over very quickly, with inmates bonding out or being released after serving a short sentence. Having jail intake officers identify illegal aliens at the time of booking ensures that they will be flagged for removal before release.

The correctional agreements are the clearest example of how the 287(g) program augments ICE capacity and serves as a “force multiplier.” In Arizona, for example, the state with one of the most severe illegal immigration problems, the ICE supervisory detention and deportation officer who is in charge of the Maricopa County 287(g) jail operation manages a staff of five ICE enforcement agents. Thanks to the 287(g) program, this supervisor also has 64 Maricopa County jail employees under his purview who can screen and process criminal aliens on behalf of ICE.10 Removing the criminal aliens they find saves money for the county; having 64 additional immigration status screeners increases ICE productivity exponentially.

While the delegation of authority has allowed the 287(g) officers to put any illegal alien on the path to removal, due to resource constraints, lack of detention space, or policy reasons, most participating agencies have decided to focus their enforcement authority on certain groups. For example, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office uses its authority to target gang members in custody. In Rockingham County, Va., the 287(g) booking officers consider immigration charges for any removable alien who is deemed to be a threat to public safety, regardless of the level of offense that results in his or her being jailed. In all correctional agreements (and other models as well), the immigration law enforcement authority comes into play only after an individual is arrested or involved in a crime or criminal investigation; in no cases are people taken into custody or detained for the sole purpose of trying to determine their immigration status.

In the programs we examined, all foreign nationals booked into jails were questioned and screened through the ICE databases, regardless of the severity of the offense, so that warrants, prior crimes, or immigration violations could be discovered. Notwithstanding the claims of civil liberty and ethnic advocates who oppose this program, there have been no documented instances of sheriff’s deputies in 287(g) jurisdictions rounding up people on the basis of appearance or ethnicity so that they can be brought to jail and screened. If such tactics had been used, it is virtually certain that ICE would have shut down the program.

The correctional agreements have produced the largest number of arrests in the 287(g) program. It is impossible to say precisely, because 12 of the 67 agencies have combination corrections/task force agreements where the source of the alien arrests are not disaggregated, but we estimate that about 91 percent of the 287(g) arrests over the period studied were from correctional programs. (See Table 7.)

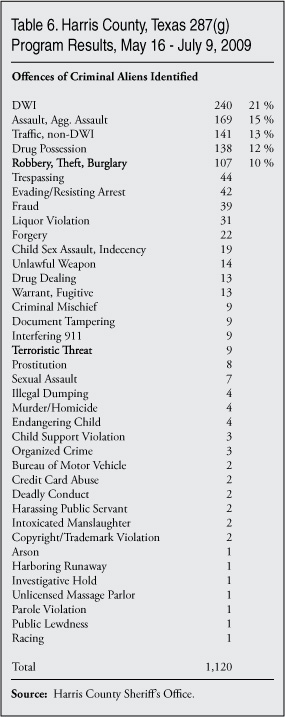

Some of these programs are turning up startling numbers of removable criminal aliens. For example, Harris County, Texas, which is one of the largest county jail systems in the country and includes Houston, issued just over 10,000 detainers in the first 10 months after implementing the 287(g) program (November 1, 2008 - August 18, 2009). These detainers were processed by eight 287(g)-trained officers, and most involved serious offenses. Only Los Angeles and Maricopa (Ariz.) counties ever process more criminal aliens, with 14 and 64 trained officers, respectively.

Lt. Michael Lindsay, who runs Harris County’s 287(g) program, says that the 287(g) program is superior to every other ICE program targeting criminal aliens. Queries to the Law Enforcement Support Center, a call center created to answer status queries from state and local law enforcement agencies, can take several hours to receive a response. Even the brand-new interoperability project of ICE’s Secure Communities Program, in which immigration status queries are done automatically in combination with the standard FBI criminal record check, can take up to four hours. One significant weakness of the Secure Communities program vis-a-vis 287(g) is that illegal aliens who do not have a prior record with ICE will not be flagged as removable under Secure Communities. Another problem is that Secure Communities currently has the capacity to process only the most serious offenders (rapists, murderers, robbers, or kidnappers). In contrast, the checks done by 287(g) officers, who have direct access to ICE databases, take only minutes. In addition, the trained officers have the knowledge and authority to question aliens about their status. They can make independent assessments of an offender’s lack of status, even if the offender does not have a prior record with DHS. These advantages result in the removal of more criminal aliens than under other programs.

For example, in late 2008 the Harris County Jail joined the Secure Communities interoperability program, which was budgeted at about $1 billion nationwide. In the first six months, the program identified 1,718 removable aliens in the county jails — certainly a contribution to public safety. But over the same time period, the nine locally paid Harris County 287(g) jail officers identified and charged about 5,000 criminal aliens, at no cost to the federal government beyond the initial $125,000 for training and set-up and $50,000 for six months of supervision. The 287(g) program clearly provides far more bang for the buck for local communities and all federal taxpayers.

Previously, Harris County had ICE agents screening aliens in jails under the auspices of the Criminal Alien Program, but these agents did not cover the night shift, which 287(g) does. Some of the most serious cases come in at night; recently an individual booked in late at night was charged with assault with a deadly weapon. The 287(g)-trained officers discovered that this inmate was the subject of two Interpol warrants for murders in Mexico. This information might have fallen between the cracks without the full-time, comprehensive screening made possible by dedicating local officers to the 287(g) program.

Highway Patrol

A handful of jurisdictions — the Colorado Department of Public Safety, the Alabama State Police, the Missouri State Highway Patrol, and the Georgia Department of Public Safety — have implemented 287(g) programs in a highway patrol setting. While it has not been widely used this way, highway patrol was one of the uses originally envisioned for the 287(g) program. The main purpose is to address the threat to public safety posed by alien smuggling on the nation’s highways.

Today, because the land borders and ports of entry are more tightly controlled, smuggling organizations offer one of the primary methods for possible entry by illegal aliens, terrorists, and other criminals. Alien smuggling organizations routinely guide and transport large and small groups of illegal immigrants from border areas or airports to final destinations around the country, usually by the vanload. They pack as many people as possible into vehicles and travel at high speeds for long periods of time over long distances. The smugglers are not concerned with the safety of the vehicle, the passengers, or the other drivers on the road.

As with other types of illegal immigration-related crime, ICE must focus its resources on investigating and prosecuting the larger and/or more dangerous smuggling organizations, and cannot patrol the major routes, nor even investigate every case, much less react to remove every alien who participates in smuggling. Local LEA partners can help fill this gap in enforcement, as every state has a highway patrol.

The impetus for Colorado’s 287(g) highway patrol program came after a string of four serious vehicle accidents involving alien smuggling on Colorado highways that occurred within a 24-hour period in 2006, one of which happened to be observed by a state legislator participating in a ride-along with a Colorado trooper. Over 100 illegal aliens were taken into custody in those four incidents. At the time, the State Patrol estimated that it encountered over 500 illegal aliens per week in the course of regular duties, or more than 26,000 per year. At the same time, the agents in the local ICE office were focused on criminal investigations and identifying illegal aliens who were incarcerated, not on addressing alien smuggling.

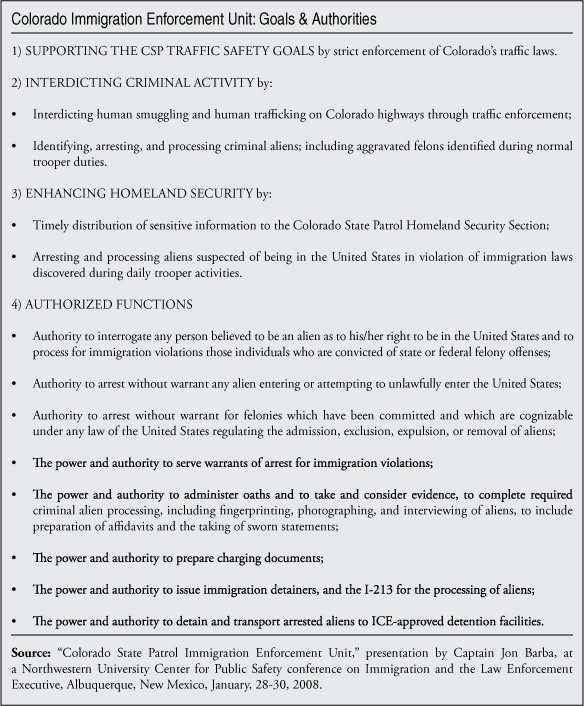

Soon after the series of accidents, members of the state legislature worked with the Colorado State Patrol (CSP) to create and fund a new Immigration Enforcement Unit. The legislature provided funding for 23 uniformed state troopers, who completed the ICE 287(g) course in 2007. Troopers are deployed based on statistical information on known human smuggling and trafficking routes and concentrations of immigration violations. Emphasis is on highway safety and disrupting alien smugglers who endanger the lives of others on the road. “We go out like any other state trooper to enforce traffic laws. But if we come across any cases we suspect to be human smuggling, we have the authority to take them in,” says CSP trooper Rob Hampton.11 According to former unit Captain Jon Barba, the main benefit of the program has been the ability to accurately identify certain aliens encountered on traffic patrol, so as to prevent the release of individuals of national security interest, wanted criminals, imposters, human smugglers, and serial immigration violators. Only those who have displayed unsafe or suspicious behavior are screened, (e.g., DUIs, unsafe vehicles, speeders, and revoked licenses.)

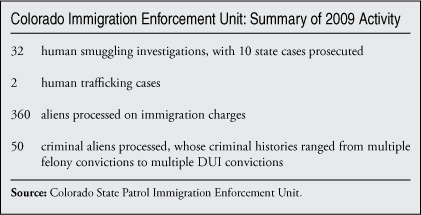

According to CSP documents, the unit uses the 287(g) authority as follows:

- when immigration issues or violations are discovered during daily state troopers’ duties;

- during the investigation of human smuggling and human trafficking cases;

- during the investigation of cases involving criminal extortion or coercion or involuntary servitude;

- contacts involving foreign nationals who are criminal aliens, aggravated felons, or multiple traffic offenders;

- on vehicle contacts containing a number of illegal aliens during which the vehicle is determined unsafe due to serious mechanical defects and/or unsafe loading (excessive occupants for the vehicle’s design).

For more detail on these authorities, see “Colorado Immigration Enforcement Unit: Goals & Authorities.”

There is no question that the two state programs together have vastly increased the identification, prosecution, and removal of criminal aliens in that state. Over the life of the program, the Colorado Immigration Enforcement Unit has made 1,156 immigration arrests, of which 777 were in 2008. In addition, the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office 287(g) program added another 177 arrests in 2008. The ICE investigations office in Denver, which covers Colorado and several surrounding states, made a total of 1,594 arrests in 2008.

According to Todd James, a CSP spokesman, there have been no more alien smuggling related fatalities on Colorado highways since the 287(g) program began there.12

Traffic Stops Yield Significant Arrests

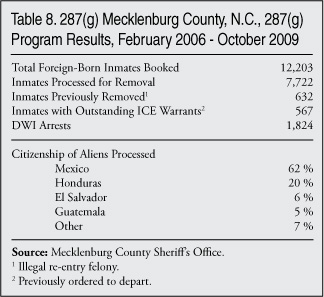

Much of the recent criticism of the 287(g) program has centered on allegations that the aliens being arrested are not “serious” criminals. Critics point to large numbers of illegal aliens who are apprehended as a result of traffic offenses and suggest that this demonstrates that 287(g) officers engage in anti-immigrant ethnic profiling. Indeed, in many of the 287(g) jurisdictions we examined a significant number of the arrests are for traffic offenses (as is the case in many non-287(g) jurisdictions as well). However, not all traffic offenses are minor; they can range from failure to use a turn signal to vehicular homicide. Drunk driving is one common traffic offense that snares illegal aliens. In Mecklenburg County, N.C., where several people have been killed by illegal alien drunk drivers in recent years, nearly one-fourth of the aliens processed for removal have been arrested for DWI. (See Table 8.)

Law enforcement agencies defend these traffic enforcement programs by emphasizing that they are aimed at those who break laws, not any particular ethnic group. Says Frederick, Md., police chief Kim Dine: “We obviously engage in aggressive traffic enforcement because anybody in policing knows that that is also an effective way of dealing with crime.” He points out that while two-thirds of the 287(g) arrests in his area were associated with traffic violations, many of those traffic offenders turned out to have records of prior crimes, in particular drug trafficking and gang crimes, including four members of MS-13, the notoriously violent Hispanic gang comprised mostly of illegal aliens.13

Task Force/Investigative Model

More than half of the agencies using 287(g) have elected to have task force, or investigative, agreements. While these account for far fewer arrests overall than the correctional agreements, the task force agreements provide maximum flexibility for the agency to use 287(g) for local crime-fighting priorities that are not limited to a correctional or patrol setting. Officers in these programs can take advantage of the unique and powerful investigative authorities that immigration law provides, which can be enormously helpful in criminal investigations, especially in tackling drug, gang, and organized crime.14

Florida

The very first 287(g) MOA was a task force agreement signed by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) soon after 9/11. Initially it was designed to support the investigations pursued by newly formed domestic security task forces. The FDLE now has 62 officers who have received 287(g) training. The focus of the task force is on preventing a terrorist attack, and the 287(g) authority has been used to investigate foreign nationals suspected of involvement in suspicious activity or who were working around critical infrastructure. For this law enforcement agency, the key benefit is direct access to the ICE databases, which enables officers to determine accurately the status of foreign nationals who are the subjects of their investigations. The program has made just a few arrests (20) in recent years, but these included individuals who were surveilling sensitive locations and other aliens who were employed at airports and nuclear power plants.

After trying the program, the FDLE trained more officers and expanded the scope of its investigations to other non-security crime problems. Thirty-nine agencies in Florida now have 287(g)-trained officers, including 23 county sheriff’s offices; the police departments in Miami, Clearwater, Ft. Lauderdale, Ft. Myers, Hollywood, Miami-Dade County, St. Petersburg, and Tallahassee; and five state agencies, including the Agriculture, Fish & Wildlife, and Transportation departments and the University of Florida.

Alien Crime Units

The investigative/task force option has enabled other agencies to create specialized alien crime units to support other officers in the agency, as Prince William County, Va., and Beaufort County, S.C., have done. Alternatively, it allows neighboring jurisdictions to combine forces to address common crime problems related to immigration, as has been done in Arkansas and Florida. Most of these arrangements are in rural locations that are far from ICE field offices and would not otherwise have access to these immigration law tools.

In addition, the 287(g) authority and access to immigration records is very useful for detectives or investigators working specialized cases, such as drugs, gangs, document fraud, or vehicle and driver’s licensing. Officers can question and investigate foreign-born individuals who are still at large or under suspicion. They can use immigration law tools in pursuing complex investigations in areas such as organized crime, human smuggling, drug trafficking and distribution, gangs, and document fraud. Jail and patrol agreements simply do not provide the flexibility needed for investigations that aim to systematically address a crime problem or to dismantle criminal organizations.

Having 287(g) authority greatly improves a local agency’s ability to identify foreign individuals and any previous criminal history and greatly improves their intelligence gathering, according to the Collier County, Fla., Sheriff’s Office, which has set up a Criminal Alien Task Force. The task force is multi-functional and supports all the other Sheriff’s Office divisions — the jail, the human smuggling unit, intelligence, driver’s license investigations, street gang units, the fugitive warrants bureau, marine issues, road patrol, and other investigations. It has enabled task force officers to apprehend and put on the path to removal a number of “violent, felony career criminals who otherwise would not have been identified,”

including:

- An individual with multiple prior arrests for child molestation;

- A prior deportee wanted in another state for child rape and a firearm offense, also suspected of murdering his eight-month-old daughter;

- An individual arrested multiple times for robbery, burglary, drugs, and firearms charges who had used a false birth certificate to obtain a U.S. passport and a driver’s license;

- An MS-13 gang member previously deported from another state after a gang-related shooting.15

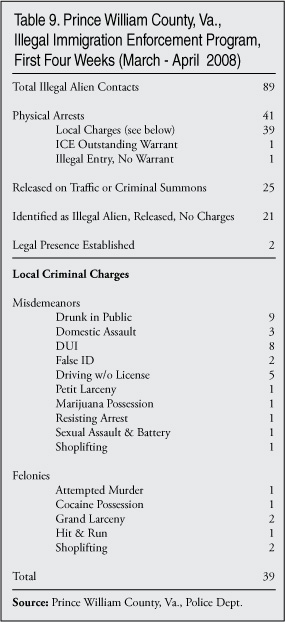

Prince William County, Va., is one of a handful of local police departments to use 287(g) for a specialized unit devoted to alien crime. The county established its Criminal Alien Unit on March 3, 2008, as part of a comprehensive public safety strategy. This strategy included the adoption of a policy mandating that all individuals taken into custody for a state crime must be screened for immigration status. All officers on the force received basic immigration law training for this purpose. Aliens who are suspected to be illegal or removable are referred to the six-officer Criminal Alien Unit, which has 287(g) authority. Depending on the person and the crime, the aliens identified may be released or held on immigration charges in addition to other state charges.

The data from Prince William County contradict accusations from critics that 287(g) agencies are using the authority to slap minor charges on people who appear to be immigrants, for the sole purpose of trying to have them deported (as if police officers actually would have time or interest in such activity). In the first four weeks of the program, during the regular course of their duties, Prince William police officers encountered 89 people they had probable cause to believe were illegal aliens. Of those, 41 were physically arrested — 39 on local charges, and two on immigration charges brought by officers with 287(g) authority. Of the remainder who were not arrested, 25 were released with a traffic or criminal summons, 21 were determined to be illegal aliens but were released without immigration charges, and two were determined to have legal status. Table 9 shows the specific charges of those who were physically arrested.

Costs

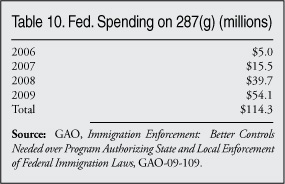

The 287(g) program has proven to be cost effective, both for ICE and for local law enforcement agencies. Table 10 shows the funding provided by Congress for 287(g). The number of agencies participating and the number of 287(g) arrests both have risen quickly as Congress has injected money into the program. However, even as Congress increased funding in FY 2009 under the Obama administration, DHS has slowed the pace of new participants. At this writing, it has not been determined what the level of funding will be for 2010. The House of Representatives provided an increase to $68 million, but the Senate approved only $5.4 million, equal to the amount of the Obama administration’s request, which appears to be for new supporting agreements.

ICE expenses for the program include training, equipment, and supervision. The cost for training each officer is estimated to be $2,622 if conducted at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Georgia, or $4,840 if conducted at another site. ICE spends an average of $80,000 per agency for the initial set-up of equipment, including computers and a secure transmission line, and another $107,000 per agency for annual operations and maintenance.16 Supervision is provided by the local ICE field office, typically with existing personnel, who manage the program along with other duties.

The 287(g) program is a bargain compared to other immigration law enforcement programs, especially those targeting criminal aliens, such as Secure Communities and Fugitive Operations. In FY 2008, ICE spent $219 million to remove 34,000 fugitive aliens (who are mostly criminals). That same year, ICE was given $40 million for 287(g), which produced more than 45,000 arrests of aliens who were involved in state or local crimes. The main reason 287(g) is so cost-effective for ICE is because the local agencies cover the cost of the personnel who screen and arrest the illegal aliens, making it a true force multiplier.

Although opponents of 287(g) often maintain that the costs to local agencies of participating in the program outweigh the benefits,17 in fact most participating agencies report that it actually saves them money, even in the short term. First of all, when ICE accepts custody of an incarcerated alien for removal, ICE will reimburse the local jail for the cost of holding him or her, thus imposing no additional costs on the local agency for jailing the removable alien population.

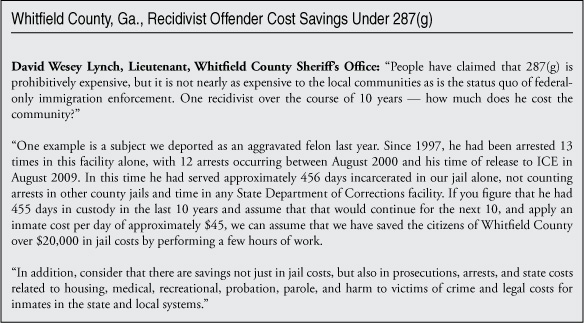

Even more important, a number of 287(g) agencies report that the identification and removal of criminal aliens has, over time, reduced the size of their total inmate population. According to Lt. David Wesley Lynch, who runs the Whitfield County, Ga., jail 287(g) program, that program has resulted in the deportation of 400 criminal aliens, which has in turn helped bring about a reduction in the total jail population for the first time ever. (See sidebar below.) This drop has occurred because serious offenders were removed as well as so-called minor, but chronic repeat, offenders. In addition, Whitfield County has seen a drop in the number of arrests overall, at a time when many agencies are reporting increases in crime due to the economic crisis and high unemployment.18

Other agencies in different parts of the country report similar results. Commander Michael Williams, who runs the Collier County Sheriff’s Office 287(g) jail and task force programs, says 287(g) is one major factor, together with a drug court and diversion program, that has enabled the county to close one of its jails, saving the county about $550,000 in annual operating costs. The program removes 20-30 inmates each week, with more than 1,500 detainers placed as of May 2008. Prior to starting 287(g), Collier County estimated that one-fourth of its jail population was illegal aliens, costing the county about $9 million per year.19

Sheriff Daron Hall, of Davidson County, Tenn., reports that after two years of using 287(g) his jurisdiction has experienced a 46 percent decline in the number of illegal aliens committing crimes and a 31 percent decline in the number of foreign-born individuals arrested. The federal government has reimbursed the county $61 a day for illegal aliens detained, for an estimated total of $1 million in 2009. So far, only a tiny fraction (1.3 percent) of those removed through 287(g) have returned and been re-arrested in the county.20

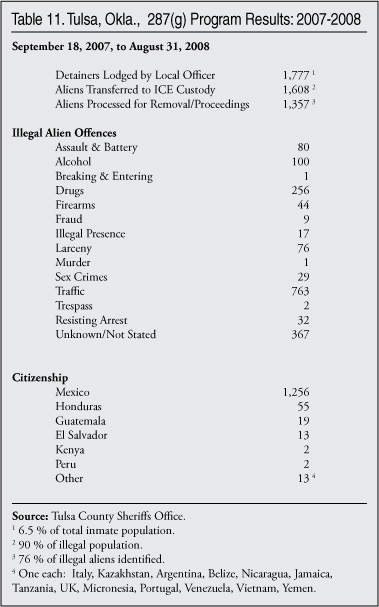

The Tulsa, Okla., Sheriff’s Office reports that its jail population decreased by 7 percent one year after starting 287(g). Its budget did not increase, and no staff were added. A spokesman calls it “a money-making project,” as ICE reimburses the jail $54.13 per day for each of its detainees.

Participation

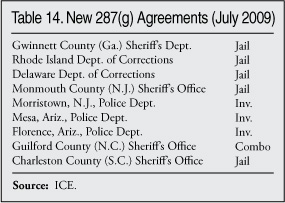

Interest in 287(g) has skyrocketed in the past several years. Today, nearly 1,000 officers from 67 state or local agencies participate in the program. Eleven new agreements were announced in July 2009, and about 30 are reportedly on the waiting list.

While its growth has been dramatic, the potential for expansion of 287(g) is huge. It has occurred with little encouragement from ICE; in fact, the growth of the program is more due to word of mouth among law enforcement agencies, news media accounts, and pressure from political leaders and community activist groups concerned about crime associated with illegal immigration. For years DHS and ICE resisted expanding the program, citing a lack of resources to meet demand and lack of adequate bed space to house the large numbers of removable aliens who would be identified. ICE has contended that some of the agencies that are applying do not really need it, and tried to steer them toward the catch-all ICE-ACCESS program (http://www.ice.gov/pi/news/factsheets/access.htm). ICE has further discouraged prospective applicants by dragging out the application and approval process with what are described by applicant agencies as endless, repetitive, unproductive meetings after meetings with Oz-like layers of bureaucrats. In many instances, the only thing that has cut through the red tape and gamesmanship has been the active involvement of congressional representatives.

Organized Opposition

In addition to the struggle with ICE, local agencies often encounter organized resistance from local activist groups that traditionally oppose immigration law enforcement, such as the ACLU and ethnic advocacy groups. These groups are reinforced by their national counterparts, which have over the years developed an extensive tool kit of how-to manuals and talking points to help local activists try to shoot down proposed 287(g) agreements.21 Anti-287(g) advocacy extends even to the legislature in Mexico; a member of the Mexican Senate recently denounced the program, calling it a clear violation of the human rights of Mexicans.22

Advocates justify these efforts with an array of studies that claim to establish that 287(g) agreements lead to:

- rampant racial profiling, as local law enforcement officers focus on arresting people who appear to be immigrants in order to have them deported;

- round-ups of innocent or unfairly targeted immigrants on trumped up or minor local charges;

- a deterioration in public safety overall as immigrants become so fearful of local law enforcement authorities that they will refrain from reporting crimes;

- police distraction from more important crime-fighting because they spend too much time on immigration law enforcement.

In addition, 287(g) opponents often cite academic studies claiming that immigrant crime is insignificant and less common than the crimes committed by native-born Americans.

Despite being repeatedly invoked in discussions on 287(g) or immigration law enforcement at the local level, none of these claims holds up under scrutiny, and none is consistent with the actual experience or events in the 287(g) jurisdictions. All agencies we interviewed reported having no complaints filed accusing officers of racial profiling, much less any documented abuses. There have been allegations made by community organizations and politicians in a number of 287(g) jurisdictions but, as reported in a GAO study, to date there have been no substantiated cases of racial profiling or abuse of immigration authority in any 287(g) location. This should not be surprising, as the 287(g) training emphasizes how to avoid racial profiling. In addition, most U.S. law enforcement officers today are well aware of the sensitivity of this issue, and receive considerable training throughout their careers on how to prevent it.

Similarly, no 287(g) agencies have engaged in street sweeps or round-ups for the sole purpose of questioning members of the community about their immigration status. All 287(g) operations and activities have been conducted in the context of criminal investigations or arrests, and for legitimate law enforcement purposes. DHS has yet to report on a single instance of a local agency overstepping its bounds or authority. Apparently lacking any actual incidents, opponents such as the ACLU and Catholic Charities have staged outreach events in various parts of the country, including Georgia and Maryland, to encourage individuals to file complaints.

While it is true that a significant number of those charged with immigration violations under the 287(g) program were arrested for lesser or non-violent offenses like minor traffic violations, this is not necessarily a sign that agencies or officers are abusing their authority. Many of the correctional institutions screen all those who end up in jail, and if they are found to be in the United States illegally, generally they are removable. Some are held in custody until the disposition of their local and immigration cases, but many are not. Many are given voluntary departure or released pending an immigration hearing.

While many of those charged with immigration violations came to attention of law enforcement as a result of a traffic stop or minor crime, because of 287(g) officers are able to complete a thorough screening of the aliens’ background by using immigration databases and often find out that quite a few of the so-called minor offenders have prior criminal histories that include more serious offenses. A significant percentage have been deported before, and others have multiple arrests in the same jurisdiction or have fled there from another area.

Even in other ICE programs (as in law enforcement in general) the majority of criminal alien removals result from misdemeanor arrests, not felony arrests. The Costa Mesa, Calif., Police Department, for example, which participates in ICE’s Criminal Alien Program (CAP)23 in lieu of 287(g), provided us with statistics covering 11 months of arrests in 2008. A total of 4,765 adults were booked into the Costa Mesa jail from January to November 2008. The ICE agent assigned to the jail screened 609 foreign-born offenders and placed immigration holds on 309. Of those ordered held pending possible removal, only one-fourth (86) resulted from a felony arrest and three-fourths (223) resulted from a misdemeanor arrest. In Irving, Texas, which also participates in CAP, nearly 12 percent of those arrested were illegal aliens, but only 9 percent of those flagged by ICE screeners were arrested on felony charges at that particular time, while 63 percent were charged with misdemeanors, 16 percent for drunk driving, and 12 percent for driving without a license.

The Chilling Effect Myth

One of the most common concerns voiced in opposition to 287(g) agreements, and to any form of cooperation between local LEAs and ICE, is that if local agencies become involved with immigration law enforcement, immigrants in their jurisdiction will become so intimidated and fearful of local authorities that they will refrain from reporting crimes or assisting with investigations, leaving these crimes unsolved, and the perpetrators unpunished. Known as the “chilling effect,” this theory is promoted by a number of national advocacy groups, including the Police Foundation, the Major Cities Chiefs Association, and the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

The origins of the “chilling effect” theory are unclear, but hard evidence of the phenomenon is non-existent in crime statistics, social science research, or real-life law enforcement experience. National crime statistics show no pattern of differences in crime reporting rates by ethnicity,24 and the most reliable academic research available, based on surveys of immigrants, has found that when immigrants do not report crimes, they say it is because of language and cultural factors, not because of fear of immigration law enforcement.25

As just one example, an analysis of calls for service data from the Collier County Sheriff’s Office supports the view of many law enforcement professionals that the “chilling effect” is more of an irrational fear (or a politically motivated invention) than a reality. Collier County consists of several diverse jurisdictions, including North Naples, an area that is largely native-born, and Immokalee, an area with a large immigrant population, both legal and illegal. Over the first year of the county’s 287(g) program, calls for service dropped 8 percent county-wide — a rate that was consistent with the overall drop in crime that year. Even more important, both North Naples and Immokalee showed the same rate in the drop in calls for service, showing no difference between immigrant and native crime reporting after the program was launched.26

An extensive analysis of the effects of the Prince William County, Va., immigration enforcement program, which includes 287(g), reports similar results. Conducted by researchers at the University of Virginia, that study found no significant difference in crime reporting rates between Hispanics and non-Hispanics after the implementation of the county’s immigration enforcement initiatives: “[A]mong those who were victims of a crime that occurred in Prince William, the rates of reporting are nearly identical for Hispanics and non-Hispanics, and are statistically indistinguishable within the survey’s margin of error.”27

While rumors abound of illegal aliens who allegedly refrain from reporting crimes out of fear of deportation, we could find no substantiated cases of crime victims who were removed as a result of having reported crimes to authorities, unless the victims happened to be criminals as well. In fact, immigrants coming forward to report crimes is one of the main ways local LEAs and ICE are able to launch investigations against criminal aliens. However, victims and witnesses to crimes are not targets for immigration law enforcement, and this is repeatedly emphasized by ICE and local LEAs in outreach to immigrant communities.

Says Lt. Wes Lynch, of Whitfield County: “Since starting the 287(g) program at our jail, we have had more communication with the immigrant community, not less.” The sheriff has included the Mexican consulate and advocates for the immigrant community in discussing the program. Lynch says that immigrants now approach officers at the jail much more regularly and have assisted in locating criminals. For example, one individual they suspected might be an illegal alien came to the jail to report the return to the community of a drug dealer who had already been removed once before as an aggravated felon, enabling them to prosecute him on criminal immigration charges as a penalty for re-entry. Another community member, a naturalized citizen, came forward after the 287(g) program was launched to report a case of immigration-related marriage fraud.28

The 287(g) training increases local officers’ awareness of when they should consider the immigration status of crime victims — not for the purpose of removal, but to access the various special protections available to victims, witnesses, and informants under immigration law. For example, someone who is a victim of a gang crime (or any crime) who happens to be an illegal alien might be needed to testify or otherwise assist in the prosecution of the criminal. If the alien lacks status, he is subject to removal at any time. To ensure that does not happen prematurely, the local agency can work with ICE to arrange special status, temporary or otherwise, until the case is resolved. These tools have proven to be a much more powerful way to encourage cooperation from the immigrant community than non-cooperation or sanctuary policies.

Most agencies with 287(g) programs have active outreach programs in place to help ensure that community leaders understand the goals of the program and how the immigration authorities will be used. Law enforcement managers typically invite representatives of foreign consulates to observe how officers with 287(g) authority carry out their duties, and they report that the consulates are usually satisfied that the program will not be misused. Our research turned up no instances where a foreign consulate tried to block a 287(g) program. The opposition usually comes from local cause groups or branches of national advocacy organizations. One local 287(g) program manager stated that he had invited 287(g) opponents to ride along with his officers to observe operations, but had no takers. All LEA representatives we spoke with agreed that agencies participating in 287(g) should work with community advocates to help them understand that they should not stoke fear in the immigrant community by perpetuating the myth of the “chilling effect.”

Foreboding New Hurdles

The Democratic takeover of Congress in 2006 has produced a serious threat to the 287(g) program. Key Democratic leaders, such as the liberal chairman of the House Appropriations homeland security subcommittee, Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), have moved to cut funding for it after three years of growth under the Republican Congress and Bush administration. In the fall of 2008, a fight ensued in committee, breaking out along party lines. Republican appropriators attempted to amend the legislation and preserve the integrity of the program, but the Democratic majority voted against 287(g).

While the appropriations process largely broke down in 2008, the Homeland Security appropriation had passed through the committee. The bill was widely viewed as containing the policy priorities and spending allocations to be enacted early in 2009, as the new Congress and administration both came to power. The bill the House committee reported was craftily worded, and appropriations staff say it included no money for 287(g). The committee bill and its accompanying report (an explanatory document) limited FY 2009 enrollment of newly participating state and local police agencies. The bill (HR 6947, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2009 (Reported in House), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Salaries and Expenses) told Homeland Security it could not “enter into any agreement delegating law enforcement to any state or political subdivision of a state as authorized under section 287(g), other than at a jail, prison, or correctional institution ....” In other words, no patrol, task force, or investigative programs were to be approved. Any new 287(g) agreements would have to “maximize the identification of aliens who are unlawfully present in the United States and have been convicted of dangerous crimes.”29

In late 2008, Congress passed a continuing funding bill for FY 2009 that included $5.4 million (the same level as the prior year) for launching new 287(g) programs. However, the committee report’s constraints applied.

In 2009, the Democratic Congress stepped up its efforts to stifle state and local involvement in immigration enforcement, and the 287(g) program in particular. The House Homeland Security and Judiciary Committees held hearings to raise questions about the program. In January, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a congressional investigatory arm, issued an audit report that played to the new majority’s disposition by suggesting (erroneously) that the program was designed to focus on identifying aliens who have committed “serious” crimes and recommending that ICE supervise the local partners more closely to make sure this is the result.30 The auditors inexplicably assumed, without substantiation from those who created and supported the 287(g) program over the years or the program participants, that the performance objectives and results should be evaluated in terms of ICE’s institutional interests and priorities, rather than those of the local partner agencies. Despite this major analytical error, the GAO report has been used by DHS Secretary Napolitano, congressional Democrats, and other immigration law enforcement minimalists to justify further steps to try to constrain how the local partners can use their delegated immigration authority.

The FY 2010 funding further constricts the 287(g) program. House appropriators, armed with the GAO report, proceeded to “require ICE to cancel any 287(g) agreements” where supposed violations of the MOA have occurred. They devoted much funding to “expand oversight,” praised the administration’s move toward uniformity in 287(g) agreements, and ordered ICE to re-negotiate all existing MOAs.31

The Obama administration in July 2009 announced a new MOA template for all participating agencies, and gave them 90 days to sign the new version. At this writing, none has gone into effect, so it is unclear how the new rules will affect the existing programs, if at all. While ICE reportedly has adamantly refused to make even the smallest revisions to the new MOA, a number of the agencies are negotiating side letters that will individualize the new agreements.

In general, the new MOA tries to constrict local officers’ use of the immigration enforcement authority for investigative purposes to situations that the ICE supervisors can monitor more easily, a move clearly intended to discourage use of the authority for “random street stops” (which were non-existent anyway). It asks jurisdictions to align their use of 287(g) authority with ICE’s priorities for the removal of illegal aliens, which give priority to the most serious offenders. It spells out more specifically the level of ICE supervision expected for each local program. It requires local agencies to pick up some of the technology and equipment costs for database access, which could turn out to be a hardship for some agencies, especially the smaller ones ICE would like to discourage. It requires local agencies to track the nature of the offenses committed by aliens arrested, but forbids them from disclosing this information to the public unless ICE approves. The release of all information related to 287(g) programs will be controlled by ICE. This last provision has been particularly controversial, as some states have strict open records laws, and many participating agencies have invited public scrutiny of their programs to help defuse criticism from opponents.

Even before the new MOA was released, ICE announced to its 287(g) partners that it would begin to limit more strictly the number and type of criminal aliens that it would take into custody for removal. Senior ICE managers reportedly told participating agencies in a conference call in June 2009 that the agency generally would no longer accept custody of “minor” offenders so that they could preserve limited enforcement resources for “serious” criminals. A number of participating agencies have expressed concern about this approach, noting that many of the so-called “minor” criminals are actually habitual offenders and/or have serious prior offenses.32 Besides, while their state and local offenses might be considered minor to ICE, still they are a burden to the local community and its criminal justice system, and as illegal aliens, they are subject to removal, whether they commit other crimes or not.

The Obama directive is plainly an attempt to curb the flexibility Congress originally built into the program for designing locally appropriate solutions. The changes give ICE headquarters and the DHS front office the opportunity to second-guess how local agencies use the authority, and also prevent them from going beyond any policy limits ICE might wish to establish on enforcement. For example, ICE might decide that arrests of illegal aliens involved in reckless driving, identity theft, business licensing or zoning violations, vandalism, or small-time street gang activity are of no interest to the federal agency, regardless of the impact these crimes have on quality of life in the local community.

The new MOA brings to the 287(g) program a level of regulation and control that implies a certain distrust of the local agency partners.33 For example, under the new draft template for Standard Operating Procedures for Task Force Officers, ICE is proposing that local 287(g) task force officers may not even ask an alien about his status without first obtaining permission from the ICE supervisor, “who will approve the exercise only to further the priorities of removing serious criminals, gang members, smugglers, and traffickers.” This proposed requirement is puzzling, since most local law enforcement agencies already permit their officers to question aliens who are in custody about their status (courts have found that such questioning is not a civil rights violation) and these officers do not need anyone’s permission to call ICE’s Law Enforcement Support Center with the same question. Since there have been no documented cases of “loose cannon” local officers to date, this distrust seems to be based on ideological or political views on how immigration law enforcement should be carried out (or not carried out) rather than on any actual problems with how the program is being implemented.

While it remains to be seen what effect the proposed changes will have on existing programs, the clear intent of the current congressional majority and Democratic administration toward this program is worrisome to the law enforcement-minded. The House appropriations committee and the policy committees of jurisdiction are clearly bent on trying to limit the contributions of state and local law enforcement to immigration law enforcement.

Still, participating agencies are enthusiastic about continuing with 287(g), and believe that the new MOA will not significantly affect their programs. For one thing, every agency already was focused on identifying criminal aliens who pose a threat to public safety as the highest priority. Those aliens who have been identified for removal under 287(g) have already been involved in other lawbreaking, or suspected of involvement, in addition to their immigration violations. While some of the representatives of the agencies we spoke with about the changes might resent the micromanagement and implications of abuse, others are more concerned about ICE shifting some of the start-up costs to the local partners. But the biggest concern seems to be about the consequences of ICE declining to take custody of many of the criminal aliens they identify.

Recommendations

It is clear from ICE managers’ reaction to the level of interest in securing 287(g) agreements that the federal agency has felt overwhelmed. They know that they cannot meet the demand for enrollment and fear that 287(g) expansion will drain ICE resources and distract field offices from established priorities. Rep. Smith stated at a Judiciary Committee hearing that ICE had received 69 new applications in fiscal 2007 and rejected the majority, supposedly because of funding limitations.34

Even more disconcerting, under cover of “prioritization,” the new DHS and ICE leadership seem intent on minimizing immigration law enforcement so that it applies only to the most serious and egregious offenders, and passing on the rest. Making it difficult for the local agency partners to exceed ICE’s self-imposed limitations seems to be a key part of this agenda.

Most everyone would agree that removing criminal aliens should be one of the highest priorities, but it should not be the only priority. And, the new agency leadership (supported by key Democratic leaders in Congress) is explicitly rejecting the notion that routine enforcement of immigration laws has a role to play in maintaining public safety and disrupting serious criminal activity (the “broken windows” approach). Many believe that by devoting some resources (or allowing local agency partners to do so) to enforcing more routine immigration offenses, ICE could thereby reduce the number of not only routine, but repeat and more threatening immigration offenses — not to mention reducing corollary offenses, such as ID theft, document fraud, gang crimes, etc. While such an approach might mean greater demands on resources in the short term, the reduction in the medium- and long-term of all kinds of lawbreaking, including immigration law-breaking, would translate into long-term savings.

To narrow the significant gaps between local needs and ICE capacity and DHS policy goals, some adjustments are necessary that would support the public safety goals everyone can agree on while providing local agencies with the ability to supplement what ICE is willing and able to accomplish.

Resources for Detention

First and foremost, ICE needs to have the necessary resources to support a healthy, expanding 287(g) program. The most significant tangible matter to be addressed is increased funding for detention space. According to nearly every law enforcement agency we asked, the lack of funding for detention space is the biggest obstacle to increasing removals of criminal aliens. Without funding for detention space, agencies are forced to practice triage. They end up releasing many of the criminal immigration violators they identify, even those who may be considered serious and/or repeat offenders.

The aforementioned GAO report analyzed 2008 data from 25 participating 287(g) agencies. It found that these agencies had charged 43,000 aliens with immigration violations. ICE took custody of 34,000 of these aliens (79 percent). Of the aliens turned over to ICE, 44 percent (15,000) were offered voluntary departure. Fewer than half (14,000, or 41 percent) were placed in removal proceedings. The remaining 15 percent were either released or sent to prison.35

Prior government studies have shown that only a fraction of those who are not detained prior to removal will actually leave the country, and that a large share of those offered voluntary departure do not depart.36 Therefore, the lack of funding for detention space severely diminishes the effectiveness of 287(g) and represents a return to the “catch and release” policies of several years ago. It is hard to see how this approach will increase the number of criminal aliens removed, which is the Obama administration’s stated objective for the program.

For many local agencies, having to release the removable criminals they identify defeats the purpose of having the 287(g) authority and can have tragic consequences, as many of these individuals re-offend. For example, Davidson County has reported that 75 percent of the vehicular homicides committed by illegal aliens would have been prevented if the illegal alien had been deported on the basis of prior misdemeanors committed.37 When ICE issues the order to release those it cannot hold, it essentially takes responsibility for those criminals and the crimes they might later commit. If past experience is any guide, this policy is likely to backfire on ICE as many of these offenders continue or even escalate their criminal behavior, and local agencies will be able to document that ICE had its chance to remove them and failed to do so. It remains a mystery to many observers why ICE prefers to accept this responsibility rather than seek additional resources to help do its job.

Several states, including Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, which are anxious to have more criminal aliens removed, have submitted practical and detailed proposals to ICE offering to construct additional facilities, at no up-front cost to ICE, in anticipation of receiving future contracts or reimbursement for housing the surplus of immigration detainees. However, ICE apparently has not acted on many of these proposals, to the great frustration of these state governments.

In the case of South Carolina, after ICE told county sheriffs in a series of discussions that ICE would much prefer to have state-wide or regional cooperative agreements, in November 2007 a group of state law enforcement agencies submitted a detailed and innovative proposal to deal with the state’s criminal aliens.38 They proposed to create three regional detention centers strategically located throughout South Carolina to house criminal aliens for ICE before they are removed. The centers would have been staffed by the South Carolina Department of Corrections, and would have consolidated the criminal alien population from 46 counties for expedited processing and removal, producing cost savings for both the county jails and ICE. The plan would also have eliminated the need for each county to have a separate 287(g) program.

The proposal sat at ICE for seven weeks before it received a response. The ICE response was that the proposal needed to be submitted directly to the ICE assistant secretary, which the state representative did immediately. Four months later, ICE agreed to discuss the proposal in a conference call, at which time they agreed to review the proposal. At the time of this writing, the proposal apparently is still in limbo.

Certain federal legislation would complement and enhance the 287(g) program, particularly with regard to adding resources. For example, H.R. 2406, the Charlie Norwood CLEAR Act of 2009, provides grants for state and local costs associated with arresting, detaining, and transporting illegal and criminal aliens.

Asset Forfeiture

While immigration law enforcement more than pays for itself by opening up job opportunities for legal workers and through fiscal savings for the community in criminal justice, health care, education, and other social services, because these savings are rarely directed back to the law enforcement agencies, it is important to find new sources of revenue to fund immigration enforcement. One solution is to get the immigration offenders to pay for immigration enforcement. For example, asset forfeiture programs should be reviewed to identify opportunities to create stronger incentives for local participation. Similarly, the assets and proceeds of alien smuggling rings should be seized and used to fund 287(g) and state/local immigration enforcement efforts.

Extending existing asset forfeiture laws (at the federal and state levels) to immigration and illegal employment violations would provide another source of funding for immigration law enforcement and also add another element of deterrence to discourage potential violators. When criminals rob banks, embezzle, extort funds, or sell drugs, and the government finds the money generated from the crime, it does not allow the criminal to keep the money. Similarly, those who profit from illegal immigration and illegal employment, including the illegal aliens, should not be allowed to retain earnings and other assets obtained illegally and through willful violation of U.S. laws.