Related: Press Release, Panel Video, Panel Transcript

Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Todd Bensman is a senior national security fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Related: Terrorist Knifer in France Illegally Crossed EU Border with Migrants

The irregular migrant flow was exploited in order to dispatch terrorist operatives clandestinely to Europe. IS and possibly other jihadist terrorist organizations may continue to do so.

— "European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2017"1

It remains a theoretical vulnerability but not one that terrorists have been able to exploit.

— Nicholas Rasmussen, former National Counterterrorism Center director under the

Obama administration, January 2019, regarding such infiltration over the U.S. southern border.2

Key Findings

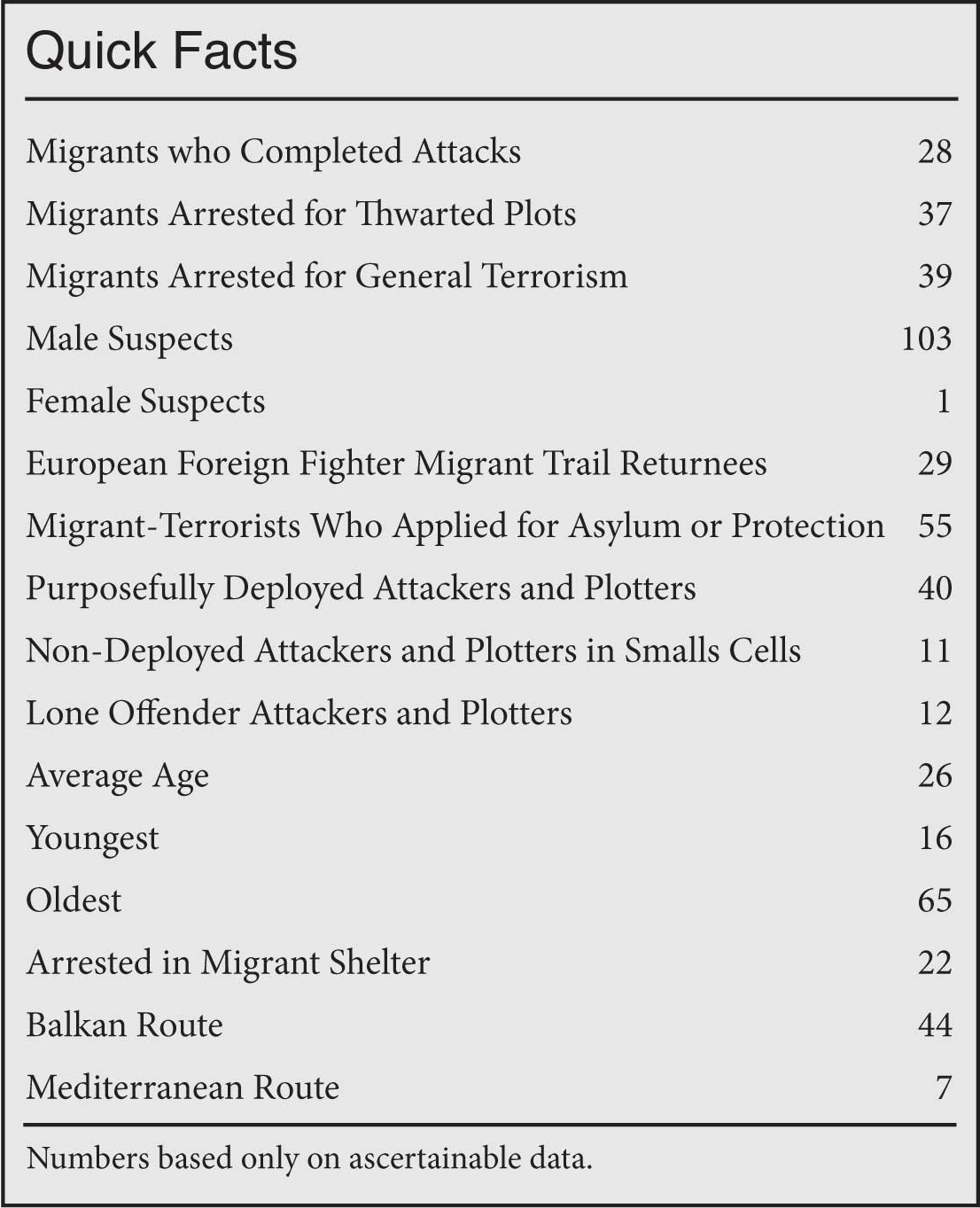

- At least 104 Islamist extremists entered the European Union's (EU) external borders using long-haul irregular migration methods between 2014-2018, establishing proof of concept for a previously theoretical terrorism travel tactic over borders.

- Of the 104 migrant terrorists identified for the 2014-2018 period, 28 successfully completed attacks that claimed the lives of 170 victims and wounded 878. An additional 37 were arrested or killed plotting attacks, and 39 others were arrested for illegal involvement with foreign terrorist organizations.

- A majority of the 104 terrorists applied for international protections such as asylum and were able to remain in European nations for an average of 11 months before attacks or arrests for plots, demonstrating that asylum processes accommodated plot incubation.

- While total numbers of migrant-terrorists were a fraction of overall irregular migration, their activities demonstrate that small numbers present outsized threats to the United States should only a few strike here. In Europe, a relative few upended longstanding political power balances, prompted a major military campaign, forced massive public expenditures on new security policies, prompted the British vote to exit the European Union, and disrupted the free movement of people within the Schengen zone.

- American security and counter-terrorism intelligence measures likely have prevented some migrant-terrorists from conducting attacks and may partly explain the absence of attacks to date from over the U.S. southern border. However, an elevated threat of terrorist infiltration via the border persists due to neglect and exploitable flaws in the American measures.

Introduction

In September 2018, the White House released its "National Strategy for Counterterrorism", outlining the nation's new counterterrorism priorities since 2011. This was the latest iteration of a tradition that President George W. Bush started after 9/11, of breaking out the terrorism threat from the broader National Security Strategy in February 2003.3 An update was appropriate because, since the last one in June 2011, much in the threat landscape had drastically changed with, for instance, the failure of the "Arab Spring", and the rise and fall of an ISIS "caliphate" in Syria.

An entirely new phenomenon on the contemporary threat stage found its way to a prominent place in the 2018 White House's National Strategy for Counterterrorism, though almost completely unremarked upon since. The strategy observed that over the previous few years, Islamist terrorists had, "to great effect", infiltrated European land borders "by capitalizing on the migrant crisis to seed attack operatives into the region."4 The document went on to frame the infiltration events of Europe as a replicable prospect for the American southern land border:

Europe's struggle to screen the people crossing its borders highlights the importance of ensuring strong United States borders so that terrorists cannot enter the United States.5

Between 2014 and 2017, 13 of the 26 member states lining the so-called Schengen Area's external ¬land borders recorded more than 2.5 million detections of illegal border-crossings along several land and sea routes, an historic, mostly unfettered surge that came to be known as the "migrant crisis".6 The Schengen Area, which generally encompasses the European Union, consists of countries that combined immigration enforcement of a common external border of 27,000 sea miles and 5,500 land miles while removing all interior border controls to facilitate the free movement of goods and people.7

During the 2014-2018 migrant crisis, the majority of travelers who crossed the external border and were then able to move unfettered between member nations came from nations in the Middle East, such as Syria and Iraq; South Asia, such as Afghanistan and Pakistan; and Africa, such as Somalia and Eritrea.8 It first became known that some ISIS terrorist operatives also were in the flows after some of them committed the November 2015 Paris attacks cited in the White House strategy, and then the March 2016 Brussels attacks.9

The White House strategy cited the prospect of Europe-style terrorist border infiltration at the American border to support various U.S. strategic goals such as: "Our borders and all ports of entry into the United States are secure against terrorist threats," and to "enhance detection and disruption of terrorist travel" by working with foreign partners to "prevent terrorists fleeing conflict zones from infiltrating civilian populations."10

The strategy document, however, faltered somewhat in citing sufficient supporting evidence for its idea that the European experience carried implications for U.S. border security, offering only that "two of the perpetrators of the 2015 ISIS attacks in Paris, France, infiltrated the country posing as migrants." Open sources were already showing considerably higher numbers than "two", but, to be fair, no concerted public-realm effort to quantify the total or analyze its meaning had occurred at that point in time.11 Other migrants in Europe were implicated in terror attacks, plots, and involvement with legally banned terrorist groups. Some had been European citizens fighting with ISIS in Syria who posed as refugees to enable clandestine entry, while others were from countries where Islamist terrorist organizations and ideologies are present.

Absent quantified analysis, electorates and leaderships have not widely acknowledged that a new innovation in terror travel had emerged, with implications for the United States. Some reporting has better quantified how often terrorists used migration methods to breach European borders, notably by researcher Sam Mullins of the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies and by Robin Simcox of the Heritage Foundation.12 But the totality of how migration and terrorism intertwined as a destructive force against Europe, and the continent's response, remains largely unacknowledged, undocumented, and not analyzed.

The purpose of this report is to further document the extent of Europe's migrant-terrorism experience, to analyze the U.S. threat, and identify European security responses that might be applicable to U.S. border security strategy.

Methodology

A key study objective was to account for the numbers of suspected terrorists who used irregular overland migration to breach European borders and who were then implicated in terroristic activities between 2014-2018, with as high a degree of probability as public reporting would permit.13 It is based on an NVIVO software-managed collection of approximately 480 media and government reports that were individually analyzed to answer the research questions.14 Much information regarding individual suspects remained behind law enforcement and intelligence firewalls. Therefore, the bulk of data for this study had to be derived from imperfect media and unclassified government reporting, a factor this study considered in its data analysis. Media reports, for instance, sometimes proved incomplete or were not updated to confirm how individuals traveled and entered the EU, or what became of their cases. European law enforcement often withheld complete names of perpetrators. This report attempted to ascribe confidence to whether specific terrorist suspects should be counted as having reached Europe via overland migration or applied for asylum and how the adjudication processes unfolded. Judgments therefore had to be made, possibly error-prone, to count individuals based on the totality and quality of reporting. Cases were categorized as "medium possibility", "strong probability", and "confirmed". Only those rated "strong probability" and "confirmed" were counted.15

This study also sought to determine the volumes and types of "terrorism events" to which the migrant-terrorist suspects could be attributed. These were defined and categorized as "completed attacks", "thwarted plots", and finally "arrests/prosecutions" for illegal extremist activities not associated with any known thwarted plot or completed attack. Among those in this latter group, for instance, were migrants prosecuted for obfuscating illegal past participation in legally banned terrorist groups or having committed acts of violence elsewhere on behalf of such groups.

Findings

Locations of 104 Known Terror-related Attacks, Plots, and Arrests by Individuals who Crossed Land Borders 2014-2018

Islamist extremists entered European external borders as migrants seeking asylum, or posing as refugees, and conducted and plotted attacks in nine countries. The border entries established proof-of-concept for a previously theoretical travel tactic and provided support for securitizing this migration.

Between January 2014 and January 2018, at least 104 Islamist extremists entered Europe by way of migration over external sea and land borders among more than two million people who crossed external European Union borders. All 104 were killed or arrested in nine European nations after participating either in completed and thwarted attacks, or arrested for illegal involvement with designated terrorist groups.

In all of these cases, the common circumstance was that the actors used illicit migration and later were implicated in specific terrorism activities, such as active plots and successful attacks, as well as past involvements that would reasonably indicate a heightened threat to destination countries.

The majority of the 104 Islamist migrant-terrorists — 75 — were primarily affiliated with ISIS, while 13 were affiliated with Jabhat al Nusra. Others were associated with Ahrar al Sham, the Taliban, Lashkar-e-Taiba, Al-Shabaab, and the Caucasian Emirate. Some had unknown sympathies and some shifted among several groups. Only one was a woman and their average age was 26. They were from Syria and Iraq, but also from North Africa and South Asia.

Completed Attacks (16)

Of the 104 migrants implicated in terrorist acts, 29 were involved in 16 completed attacks inside Europe between 2015 and 2018. These attacks killed 170 people and wounded at least 878 more, according to an analysis of media accounts. Not counted in this tally is the 2016 Christmas market vehicle-ramming attack in Berlin by Tunisian asylum-seeker Anis Amri, which killed 12 people and injured several dozen more. While his attack was noteworthy and impactful, Amri illegally entered Italy at the resort island of Lampedusa by posing as an underage refugee on a migrant boat in 2011, prior to the 2014-2018 time frame for this study.16

At least 27 were part of one large cell of operatives dispatched onto the migration trails by ISIS. Most of the 27 were involved in the two highest-casualty completed attacks: the November 2015 multi-location strikes on Paris and the March 2016 attacks in Brussels. Most of the other completed attacks were smaller in scale and sometimes involved additional deployed operatives or long-distance communications with ISIS in Syria.

Emblematic cases of such border-crossing travelers who completed attacks included:

- Mohammad Daleel, 27, was a Syrian asylum seeker who fought with ISIS and then migrated overland before blowing himself up in a July 2016 suicide bombing on a wine bar in Ansbach, Germany, injuring 15 people. Carrying a rucksack filled with explosives, Daleel earlier tried to enter a music festival attended by 2,500 people but was turned away by security. After fighting with ISIS in Syria, he traveled through Turkey to Bulgaria, and then along the Balkan route to Germany, where he was twice rejected for asylum.17 Investigators found bomb-making material in his refugee center room and a phone video pledging allegiance to ISIS. ISIS later claimed he was in regular contact as he built the bomb over three months.18

- Muhammad Riyadh, a Pakistani who traveled to Germany in 2015, ostensibly as an unaccompanied minor, had just moved from a refugee center to a foster family home when he used an axe and knife to critically injure four people in a train parked at a Wurzburg station in July 2016, shouting "Allahu Akbar." Police shot Riyadh to death. Authorities later found a hand-painted ISIS flag and martyr letter in his room, and ISIS released a video he left behind urging similar attacks.19 Riyadh first applied for asylum in Hungary in June 2015 and then at the Austria border six months later under a false name and country of origin to increase his chances of approval.20

- Abderrahman Mechkah, a 22-year-old Moroccan asylum seeker, stabbed two women to death and wounded six other women in an August 2017 attack in Turku, Finland, during which police shot and wounded him.21 Mechkah arrived in Finland in early 2016 as "part of a record wave of people fleeing poverty and violence and seeking refuge in Western Europe."22 He lived in a reception center in Turku, appeared to have been radicalized online, and was denied asylum before the attack.23

Thwarted Plots (25 Plots)

Of the 104 migrant asylum seekers involved in terrorism, 37 were involved in 25 specific and unspecified plots that police were able to foil by arresting or, in some cases, shooting those involved. Some hardly advanced beyond conceptualization. For example, Syrian national Abo Robeih Tarif was a human smuggler using boats and an ISIS member who planned to organize and film a terror attack by other operatives until arrested transporting 75 refugees in a boat to Italy.24

Other plots were farther along but did not yet have set times and locations. One example is 20-year-old Syrian refugee Yamen F., who arrived in Germany at the height of the migrant flow in September 2015 and was granted asylum while radicalizing on the internet and communicating with ISIS operatives. In October 2017, authorities arrested him for building a bomb he hoped would kill at least 200 Germans in a crowd somewhere.25

Numerous other plots had fully crystalized in terms of capability, times, and locations, but failed in execution or were thwarted, such as:

- Mohammad J., a 16-year-old Syrian war refugee who fled Damascus with his family and traveled through Lebanon and Turkey to reach Germany in January 2016, was preparing a bomb nine months later filled with sewing needles for an attack on an unspecified "soft target" in Cologne when authorities arrested him at a migrant camp.26

- Ayoub el-Khazzani, a 25-year-old Moroccan who planned to massacre train passengers on a French Amsterdam-to-Paris train in August 2015. Several commuters subdued him.27 El-Khazzani, who had legally lived in Spain, Belgium, and France, had left to fight with ISIS in Syria, and then traveled the migration routes to reenter Europe, reaching Hungary with another operative three weeks before the attack.28

- Aladjie Touray, a Gambian asylum-seeking migrant who pledged allegiance to ISIS, arrived in Sicily on a boat with 800 other migrants in March 2017. In April 2018, Italian authorities arrested the 21-year-old migrant in Naples for planning to drive a vehicle into crowds as requested by ISIS contacts.29

General Terrorism Involvement (39)

Of the 104 migrants implicated in terrorist acts, 39 were arrested for illegal past involvement with terrorist organizations outside of Europe. These kinds of arrests were predicated on atrocities committed in Syria on behalf of terrorist groups, or on other terrorism-related crimes such as kidnappings. General membership in a terrorist organization also constituted prosecutable criminality that would place individuals in a high-risk category of migrant capable of, and possibly trained, to conduct attacks in Europe. For instance, police in northern Germany arrested four brothers, all Syrian nationals, for membership in the Al Nusra Front terrorist organization, where they allegedly conducted ethnic clearing operations and plundered property of victims.30 None were implicated in any specific attack plot in Europe. Other emblematic cases include:

- Ben Nasr Mehdi, a 38-year-old Tunisian explosives expert, was arrested in 2008 and sentenced to seven years in prison after he was found to be the head of an al-Qaeda terrorist cell. He was then extradited to Tunisia. In October 2015, he returned to Europe on a migrant boat from Libya and arrived on Italy's Lampedusa island. He used an alias to claim asylum and work as a brick-layer, but his true identity was discovered with a fingerprint check.31

- Mukhamadsaid Saidov, a Tajikistani migrant who traveled to Germany with the "refugee wave" on possible orders from ISIS, was arrested in June 2016 for fighting and executions on behalf of ISIS in Syria and Iraq until he was wounded in an Iraqi air force airstrike.32 Federal prosecutors alleged that Saidov belonged to the inner circle of ISIS commander-in-chief Gulurod Khalimov.33

- Suliman al Shikh, a Syrian member of the Al Nusra Front, was arrested in 2016 after traveling via France as a refugee and applying for asylum in Germany. The 25-year-old was convicted of al-Nusra Front membership and participating in the 2013 kidnapping of a United Nations observer from Canada.34 French prosecutors accused him of providing guard duty for eight months in Syria while the group awaited ransom.35

Most migrant terrorists involved in thwarted or completed attacks were purposefully deployed to the migration flows by an organized terrorist group to conduct or support attacks in destination countries.

Of the 65 migrant-terrorists involved in completed or thwarted attacks, at least 40 appeared to have been purposefully deployed into migrant flows toward Europe, impersonating war refugees, to conduct or support attacks in Europe. ISIS was responsible for this infiltration operation.36 Eleven others apparently initiated attacks or plots in small groups of relatives or associates, not coordinated by any foreign group. The balance were self-propelled lone offenders or information was insufficient to determine whether they were deployed.

Of the 40 thought to have been deployed with training, logistical support, and plans, approximately 27 formed one single large cell of trained operatives deployed by ISIS into the migration flows, primarily on the Western Balkan route through Greece and then Hungary, to conduct terror attacks in France.37 Infiltrated cell members supported and conducted suicide bombings at six locations in Paris in November 2015, which killed 130 and injured almost 500. In March 2016, surviving cell members that were to conduct additional attacks in France changed plans under law enforcement pressure and conducted three suicide bombings in Belgium that killed 32 and injured 320. Authorities would continue to arrest or kill cell members for two more years.

In 2016, the New York Times reported, based on French intelligence material, that a clandestine "external operations" division of ISIS in January 2014 sent its first of "at least" 21 well-trained operatives to Europe camouflaged among refugee and migrant flows. He was a French citizen born in Algeria named Ibrahim Boudina, who had been fighting in Syria with ISIS, which "dispatched" him back to Europe through Greece with the intention of causing mass murder.38 Greek border police intercepted him traveling in a taxi carrying cash and an instruction manual titled "How to Make Artisanal Bombs in the Name of Allah", but allowed him to continue.39 French authorities arrested Boudina the next month for a plot to bomb the annual Cannes carnival, seizing three Red Bull soda cans filled with 600 grams of TATP, the explosive later used in Paris and Brussels, the newspaper reported.

More fighters trained by ISIS in Syria traveled the migrant routes alone or in pairs at the rate of every two to three months through the balance of 2014 and early 2015, according to the Times.40

The insertion of the Paris/Brussels cell was planned and internationally sophisticated, involving a Belgium-based fake-documents producer who created fraudulent Syrian passports that were used by returning European citizens to pose as Syrian war refugees.41 Among the operatives, "Bilal C" scouted for open borders, waiting times, refugee travel routes, and smuggling opportunities.42 A managing coordinator of Belgian nationality named Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who served as an ISIS commander in Syria, orchestrated the movement of ISIS operatives and cash along Bilal C.'s routes, sometimes transporting operatives from safe houses in Greece or Hungary to Belgium and France, where explosives and weapons were stockpiled.43 Before Abaaoud was killed in a police shootout, he told a relative he had arranged for 90 operatives to be transported into Europe among migrants, a number that has neither been confirmed nor refuted.

ISIS also apparently sent at least 13 others, in smaller cells and individuals unaffiliated with the Paris/Brussels group, to conduct other attacks. Emblematic of those sent to the migrant trails for other attacks:

- Syrian nationals Salah A., Hamza C., Abd Arahman A.K., and Mahood B. were fighting with ISIS in Syria in early 2014 when they were deployed to Germany among the migrants moving via Greece through the Balkan route.44 Two of the men left with advance orders to conduct a massacre in Germany, on the old town of Dusseldorf, using suicide vests and automatic rifles.45 They were plotting the attack from refugee centers while applying for asylum when one cell member informed police about the plot.46

- Syrian national Khaled H. was fighting with ISIS in April 2015 when the group reportedly picked him for deployment among migrants to conduct a "spectacular atrocity" on a crowded German sports stadium. Khaled H. traveled the Balkan route through Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Austria. Authorities arrested him in a refugee center among 700 other asylum seekers.47

- Tunisian national Charfeddine T. had been fighting with ISIS in Syria when he was deployed in October 2015 with a fake Syrian passport among the migrants to Germany. He was arrested in December 2016 on charges of plotting an unspecified attack in Berlin, membership in a terrorist organization, and document fraud.48 German prosecutors said the 24-year-old jihadist had been communicating, from a refugee center, with the head of ISIS's external operations division who authorized the Berlin mission.49

Other plots involved approximately 23 self-initiated lone offenders and individuals in small closed groups who likely entered already predisposed to radicalization. The data was insufficient to determine whether these offenders planned the attacks before or after arrival.

Mohammed Riyadh (aka Riaz Khan Ahmadzai) typified this group. In 2016, police shot dead the 17-year-old Pakistani asylum seeker after he attacked train passengers at a German station with an axe and knife, critically injuring four.50 Riyadh arrived in Germany a year earlier claiming to be an underage, unaccompanied minor from Afghanistan.51 The Pakistani sought asylum as an Afghan and radicalized on ISIS propaganda while living in refugee centers and a foster home. Police found a hand-painted ISIS flag and evidence suggesting he was older than 17.52

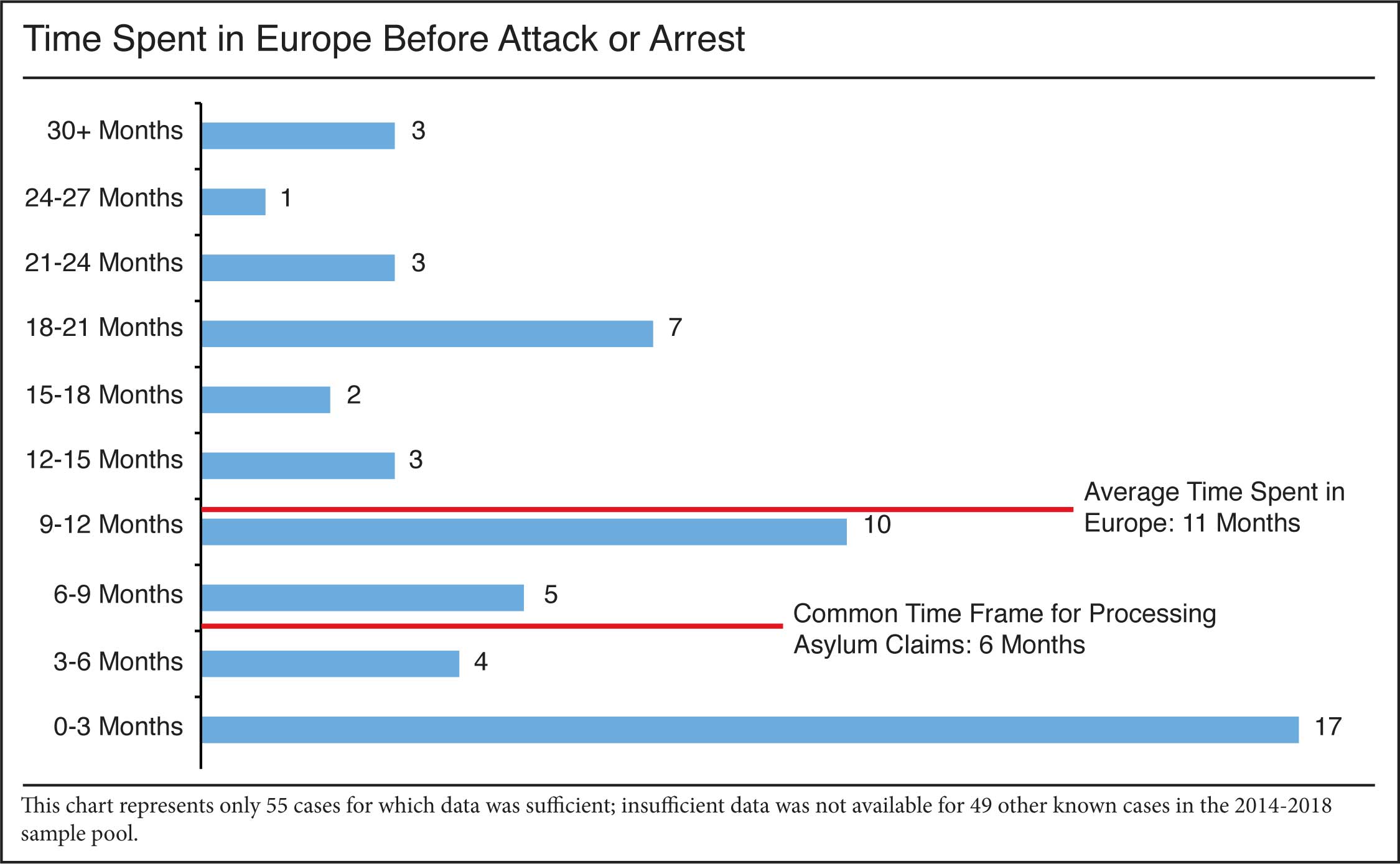

By applying for temporary protections such as asylum, Islamist terrorists who entered European external borders after migration gained legal residence with sufficient time necessary, an average of 11 months, to carry out attacks and to gestate plots.

During the 2014-2018 migrant crisis, a primary benefit to terrorists appears to have been the legal residence and time in-country enabled by Europe's processes for asylum, refugee status, and temporary humanitarian protection. The processes provided ample time for terrorists to plot, prepare, and kill.

At least 22 terror suspects were arrested while still living in migrant shelters.

Prior to 2016, European Union member states followed common procedures for granting asylum and temporary protection to people fleeing persecution or harm. Six months (not including appeals) was the recommended guideline for adjudicating applications under the Common European Asylum System prior to the crisis, with legal residence and support provided during the process.53

By early 2015, though, extraordinary volumes of migrants quickly overwhelmed the system — nearly 1.4 million asylum applicants in 2015 and another 1.3 million in 2016 — fueled by announcements by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other leaders that they would welcome all refugees.54Migrants not able to immediately apply for asylum could ask for refugee status or temporary "subsidiary protections", which entailed authorization to stay on humanitarian grounds pending more permanent status.55 Hundreds of thousands of migrants were allowed in with temporary humanitarian protection in 2016 alone.56

The recommended six-month adjudication became 11 months, which proved more than sufficient for ISIS operatives and other Islamist extremists to carry out pre-planned attacks and for plots to advance.

In the 55 migrant-terrorism cases for which there was sufficient data confirming that international protection applications were filed, including those not involved in specific plots, the average time between a border entry and attack or arrest was 11 months, with the shortest time being nine days (Bachir Hadjadj) and the longest 31 months (Munir Hassan Mohammad).

Some of the terrorists involved in the Paris and Brussels attacks were European citizens who, although posing as Syrian war refugees and traveling among them, did not all formally apply for asylum, and it was unclear what forms of temporary protection they did receive upon entry. Still, the Paris-Brussels attackers were in-country (often using fraudulent Syrian identity documents) for between one and six months before they struck, a period the operatives used to complete plotting and attack staging.

A few attackers and aspiring attackers did not apply for international protection at all once inside a target country, likely to reduce the risk of detection on the assumption that intelligence services had already identified them and would initiate arrests — or most certainly would after the first attacks began. For example, Mohamed Belkaid, a 35-year-old Algerian ISIS operative deployed with others into Europe on the Balkan route in September 2015, lived illegally in Belgium for the next six months without applying for protection. He spent the time plotting the November attacks in Paris and was preparing for his own afterward when Belgian police snipers killed him during a gun battle at an apartment where he hid with other surviving cell members.57

In 33 of the 55 cases, the time that elapsed between entry and arrest or attack exceeded the European Union's pre-crisis asylum adjudication period of six months. In 15 of those cases, the time lapse was more than twice that, exceeding 15 months. In 13 cases, the time lapse was 19 to 31 months.

Also of the 55 cases, 35 individuals who were involved in actual attacks and plots were known to have applied for asylum or refugee status. The average time in-country for these 35 was 10.9 months before they attacked or were arrested ahead of an attack.

The data pool indicates that many of these 35 terrorists took advantage of extended processing delays caused by high claim volumes. For example, one of the longest time lapses involved Eritrean asylum seeker Munir Hassan Mohammad and his British girlfriend, likewise a radicalized Muslim whom he met on a dating website after he illegally entered the UK hidden aboard a truck. Mohammed and pharmacist Rowaida el Hassan were arrested for plotting Christmas 2017 terrorist acts near London using homemade bombs and ricin poison. Mohammed had entered the UK in February 2014, lying on his asylum claim, and was working on false papers in a food-processing factory when he was arrested 31 months later, in December 2016, while living in an immigration removal center.58 His application to remain in the UK despite a deportation order was delayed in a massive backlog of unresolved asylum cases known to officials as the "not straightforward" list, which allowed him to plot the attack.

In perhaps the longest period of time after asylum application was made (some 33 months), Afghan asylum seeker Jawad S. arrived in Germany as an unaccompanied 16-year-old in November 2015 and initially lived with other parent-less asylum seekers in the small village of Piesport. He was described as an observant Muslim who prayed five times a day, though it's unclear when Jawad S. radicalized to accept violence. German authorities rejected his asylum claim in August 2017. He moved around Germany while an appeal made its way through the system, then in 2018 saw a film about how artists in the Netherlands had ridiculed Prophet Mohammed, angering Muslims worldwide. Jawad S. traveled to Amsterdam for that reason in August 2018 and stabbed two American tourists at the central train station.59

The asylum processes of Europe cannot be credited with ferreting out terrorist suspects. Many cases follow a pattern where informants, investigation, or serendipity led to arrests rather than asylum processes.

For instance, the Syrian ISIS migrant Jaber al-Bakr was granted asylum five months after he migrated to Germany and was only months afterward, due to intelligence unrelated to the asylum claim, arrested in the advanced stages of planning an ISIS-connected bomb attack using 1.5 kg. of explosives found in his apartment.60

Thanks mainly to a serendipitous informant tip, one of the shortest times between entry and a terror arrest was 11 days in the case of Algerian-born Bachir Hadjadi, a repeat drug trafficking offender and terrorism suspect who was expelled from Belgium only to return several times. After a final deportation in May 2017, Hadjadi returned that September on a migrant boat from Algeria to Cagliari, Italy. A tip from his estranged wife that Hadjadi planned to conduct an attack upon his return led police to follow Hadjadi's own brazen Facebook postings of his travel progress until his arrest in 11 days.61

In a separate case of apparent fortune, authorities were able to arrest Syrian refugee Leeth Abdalhameed within two weeks of his arrival. German anti-terrorism police arrested Abdalhameed for participating with ISIS in Syria as a mid-level commander who smuggled money, medicine, and ammunition between Turkey and the group in Syria. While no specific plot was in progress involving him, Abdalhameed initially registered and applied for asylum under a false name and had avoided providing his fingerprints, but was arrested after a fellow refugee informed on his past and his fingerprints matched intelligence information.62

A question that naturally arises is whether migrants radicalized before or after entering Europe and gaining legal residency, the implication being whether authorities might have been able to detect extremists and plots under normal or streamlined asylum adjudication processes. No clear pattern informs this question, and data is insufficient; it appears that some radicalized after arrival and did not initially enter with any specific plan to cause harm.

A June 2018 Heritage Foundation study of migrant asylum seekers who committed terror offenses in Europe found 12 of 32 terrorism cases involved those who "appeared to have begun to immerse themselves in violent Islamist ideology once they were in Europe."63 Another 10 involved those "entirely radicalized abroad".

In July 2016, at the height of migrant-terror attacks, the EU proposed new asylum processing rules that no longer mentioned the six-month waiting period and replaced it with "short but reasonable time limits".64

Though a fractional percentage of total irregular migration to Europe, the 104 migrant-terrorists caused enduring, outsized impacts on European state affairs beyond individual casualties. Small numbers of terrorists who exploit irregular migrant flows, therefore, should be viewed as high-consequence threats warranting commensurate public investment and attention in border security.

Some observers have equated low numbers of terrorists and casualties to low threat levels to individual citizens, meaning direct bodily harm, as an argument for reduced prioritization of Islamist extremism and security investment.65 But properly assessing terrorism risk requires that analysts account for effects beyond what the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime identifies as the "trauma of individual victims"; secondary and third orders of victimization include other collective harms to societies, such as impacts on trade, investment, and counterterrorism that are central to properly assessing terrorism threat and risk.66 A Rand study commissioned by the European Parliament on the broader consequences of European terrorism similarly noted that terrorism leads to significant economic effects, that European businesses, cities, and nations lost €90 billion (an acknowledged underestimation) from 2013 to 2016 due to terrorism.67

"Despite the infrequent nature of terrorist attacks", the Rand report noted, "the range of impacts on EU citizens remains significant."

No assessment of the costs and consequences associated with European terror attacks specifically attributable to migrant-terrorism during 2014-2018 could be found, likely because quantifying cases of migrant-terrorist incidents is an ongoing affair. However, if judged by the most obvious impacts on national treasuries, economic disruptions, electoral outcomes, and forced policy generation in Europe to date, the 104 migrant-terrorists provide argument that even small terrorism numbers portend greater costs and therefore threats to targeted societies. By extension, the wider impacts of what occurred in Europe warrant investment in security policy to control emigration from Muslim-majority nations.

Impacts on European societies from these 104 migrant-terrorists included:

- Electoral outcomes that saw the disempowerment of long-established political parties and increased empowerment of parties that campaigned to reduce migration and its associated terrorism.

- Accelerating a costly, three-month allied military offensive involving U.S. air power and ground troops to close the so-called "Manbij Gap" section of the Syria-Turkey border, after disclosures that migrant-terrorists used it to exit Syria for their attacks in Europe.

- The first breakdown of the 1995 Schengen Zone treaty — the free, borderless movement of people and trade among 26 states.

- The initial rise of public sentiment and calls for the UK to exit the European Union ("Brexit") as a primary means to block migrant-terrorists in mainland Europe from exploiting open borders provisions to attack in the islands.

- Concessions on once-vaunted civil liberties protections in exchange for improved counterterrorism operations and national policies that would reduce terrorism risks from the migration inflow.

- New counter-migration policies instigated to stop the attacks by reducing the volume of migrants entering the EU that carried plotters and those predisposed to conducting attacks.

Electoral Consequences

Whole nations representing tens of millions of Europeans changed political course as a result of terror attacks that killed 170 people. Parties that campaigned about Islamist terrorism and immigration gained historic ground among mainstream voters, beyond fringe nativist groups.

Explanation can be found in a content analysis of hundreds of media reports and polling data. These showed that public clamor for elected leaders to act coincided with sustained media coverage of each attack but also of funeral vigils, subsequent anti-terrorism raids, gun battles in public streets, ongoing trials, attack anniversaries, and policy debates about terrorism as associated with the migration. Citizens saw major cities transformed with security barricades and heavily armed soldiers and anti-terrorism police. Millions lived under extended civil emergency declarations.

While anti-immigration sentiment was often simplistically attributed merely to nationalist xenophobia and racial bias, polling more persuasively establishes that terrorist acts rapidly turned broader mainstream public opinion against migration from Muslim-majority countries.

A July 2016 Pew poll, for instance, showed that more than 60 percent of Europeans opposed the migration because it was associated with terror attacks and an escalated threat.68 A European Commission poll found that Europeans viewed immigration and terrorism as the primary challenges facing Europe, ahead even of economic issues.69 Pew polling for 2018, conducted after many new attacks and plots, showed that majorities in Europe (58 percent median) believed fewer or no immigrants should enter.70 Polling in 2019 of 14 EU states showed that citizens identified Islamic radicalism as the single biggest threat to the future of Europe, though not immigration itself, but also that every member state still wanted better protection of Europe's borders.71A Gothenburg University poll of Swedish voters, conducted after high-profile attacks and police raids in the country, showed 52 percent favored taking fewer refugees into the country, up from 40 percent two years earlier.72

Elections in 2017, 2018, and 2019 in almost every European country reflected widespread perceptions that acts of terrorism by recently arrived asylum seekers were linked to the immigration wave that brought them into the bloc. The perception about immigration, which had not previously registered as a significant concern, was a driving factor, albeit among others, for transformative election outcomes that included, among many other examples:

- Sweden's 2018 national election saw a voting surge for the Sweden Democrats, which campaigned against immigration and the terrorism it imported. A hung parliament emerged, with center-right and center-left blocks that had dominated Swedish politics for decades forced to include the Sweden Democrats in their ruling coalition. By contrast, the country's biggest traditionalist political party, the Social Democrats, suffered its worst election results since 1911.73

- Finland's spring 2019 national elections logged unprecedented gains for the conservative Finns Party and center-right National Coalition Party after campaigns that emphasized slowing immigration and terrorism. The Finns Party increased its seat count in parliament from 17 to 39 and emerged as the second most powerful party in the country for the first time in memory.74 The National Coalition Party also joined the ruling coalition.

- In Norway, support for the center-left, pro-immigration Labor Party fell to historic lows while voters endorsed the anti-immigration agenda of the nationalist Progress Party to the extent that it maintained its place in a coalition government as the third-largest party on a campaign emphasizing immigration issues.75

- Denmark's center-left Danish Social Democrats upended two decades of status quo in the June 2019 national election and won upset victories based primarily on its hard-line stance against immigration and pushing tough policies on asylum seekers, which attracted voters from right-wing parties it defeated.76

- Italy's 2018 national elections brought two anti-establishment parties to power in an upset, the Five Star Movement and the League party. Both won power after an election campaign dominated by promises to drastically reduce illegal immigration and to conduct mass deportations, which installed Prime Minister Matteo Salvini as head of government.77

A Military Campaign

The March 2016 suicide attacks on the Brussels airports and two other locations — by operatives deployed into war refugee flows — are credited with accelerating a U.S.-backed military campaign to close a 60-mile section of the Syria-Turkey border known as the Manbij Gap, according to reporting by the Wall Street Journal.78 The newspaper reported that in the weeks leading up to the attack, "Western officials expressed increasing alarm about the continued flow of Islamic State extremists across this 60-mile stretch of the Turkey-Syria border." U.S. officials, it said, were concerned because several of the November 2015 Paris attackers had traveled out of the disputed area and "slipped into the migrant trail in Turkey." One U.S. military official told the newspaper that until the Manbij corridor was closed, there would be no way to "cut off the foreign fighters and it will be very difficult to stop them from hiding among the migrants."

The Manbij Offensive began on May 31, 2016, to retake the town and highway over the Turkish border to deny ISIS operatives further access to the gap. The fighting involved U.S. air strikes in support of several thousand Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and small numbers of U.S. special forces.79 The offensive ended after three months, when 200 surviving ISIS fighters, using hostages, negotiated safe passage out of Manbij.80 An accounting of the cost of munitions expended during the offensive could not be found. However, media reports described some of the highest civilian casualties of the war from western air strikes there, and it should be assumed that fighters on all sides of the conflict suffered deaths and injuries.81

Breakdown of Historic Schengen Area Free-Movement Agreement

The central provision of the 1995 Schengen area of visa-free travel across 26 countries, hailed as an economic boon to intra-European trade, broke down under public pressure to stop migrant-terrorists from freely ranging among countries developing plots, like the Paris and Brussels terrorists.82 Hungary and Austria were the first to effectively leave the Schengen Area when they built walls along their borders.83

Following the 2016 Brussels attacks, six other Schengen area countries cited an "exceptional circumstances", last-resort clause to re-implement internal border checks on a temporary basis of six months, subject to renewals, on passports, visas, and luggage after the attacks.84 Belgium reinstated border controls with France. Germany reinstated controls at its borders with Austria, which did the same at its land borders with Hungary and Slovenia. Sweden reinstituted controls at harbors in the Police Region South and West and at the Oresund bridge; Denmark put restrictions on its ports with ferry connections to Germany and at its land border with Germany. Norway reinstated controls at its ports with ferry connections to Denmark, Germany, and Sweden.85

By 2019, those countries had maintained their border controls with six-month renewals, citing causes such as "severe threat to public order", "migration and security policy", and "serious threat to public policy and internal security".86Following two terror attacks in 2018, for instance, France renewed its border controls, citing "terrorist threats and [the] situation at the external borders". 87

Brexit

The Paris and Brussels terror attacks by operatives who traveled among migrants sparked the first momentum for the UK to exit the 28-member EU it joined in 1973 and set a June 2016 referendum on the matter, which voters narrowly passed. The threat of migrant terrorism spreading to the UK led to a rancorous 10-week national campaign that came to be known as "Brexit and has been described as the most significant event in Europe since the 1989 fall of the Berlin wall."88

The November 2015 attacks on Paris and the attacks on Brussels four months later set in motion Brexit's far-reaching consequences. In the years since the unsettled outcome, Brexit is now attributed to costly ongoing political divisions over its implementation, the resignation of Prime Minister David Cameron, an election that upended UK electoral power balances and reduced the power of Prime Minister Theresa May, and implementation delays. Although the UK was not part of the Schengen area free-movement treaty, the new hostility centered on EU rules permitting free movement of labor into the UK and also that EU members such as Germany were pressuring other member states to accept larger shares of migrants from Muslim-majority countries who could potentially commit terrorist acts.89

Extensive social science research since the referendum shows that public hostility toward immigration and "anxiety over its perceived effects" was sharpened by the arrival of a pan-European refugee crisis from 2015 onward and was a major predictor of support for the initial UK push to leave the EU.90 The Brussels attacks the following month and subsequent gun battles and terror attacks involving migrants, quickly built public consensus to set a national referendum for June 2016, three months after the Brussels attacks and seven months after the Paris attacks.

To be sure, other concerns predating the Paris and Brussels attacks drove Brexit, such as a currency crisis, sovereignty issues, economic recessions, and anti-establishment sentiment.91 But after the attacks and with each new one, Brexit proponents consistently made the so-called "security dividend" a centerpiece argument throughout the referendum campaign.92 Even as late as April 2018, a Center for Social Investigation poll showed that regaining control over EU immigration was the top concern of UK citizens who voted to leave.93

Analysis: Threat Implications for the United States

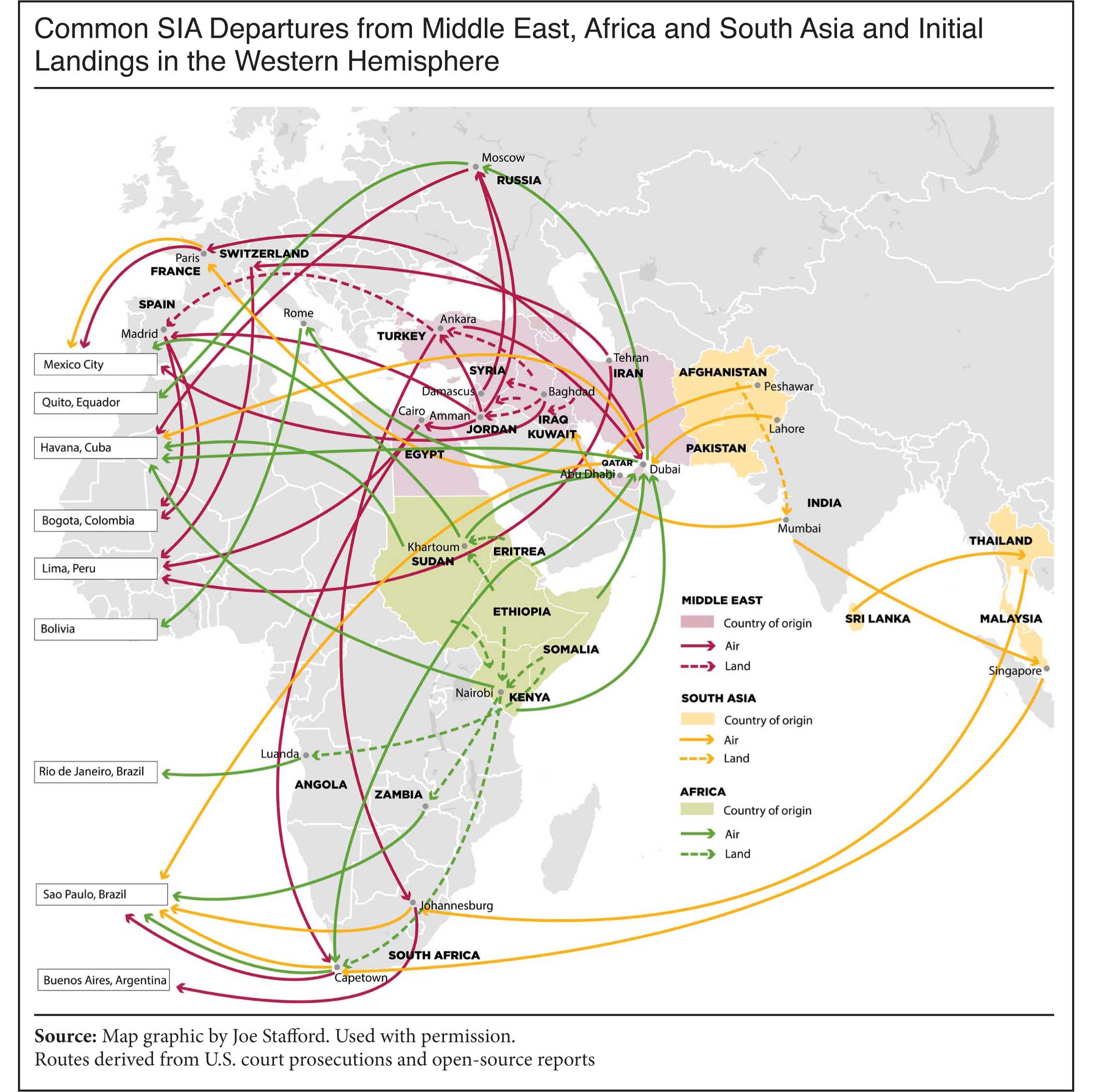

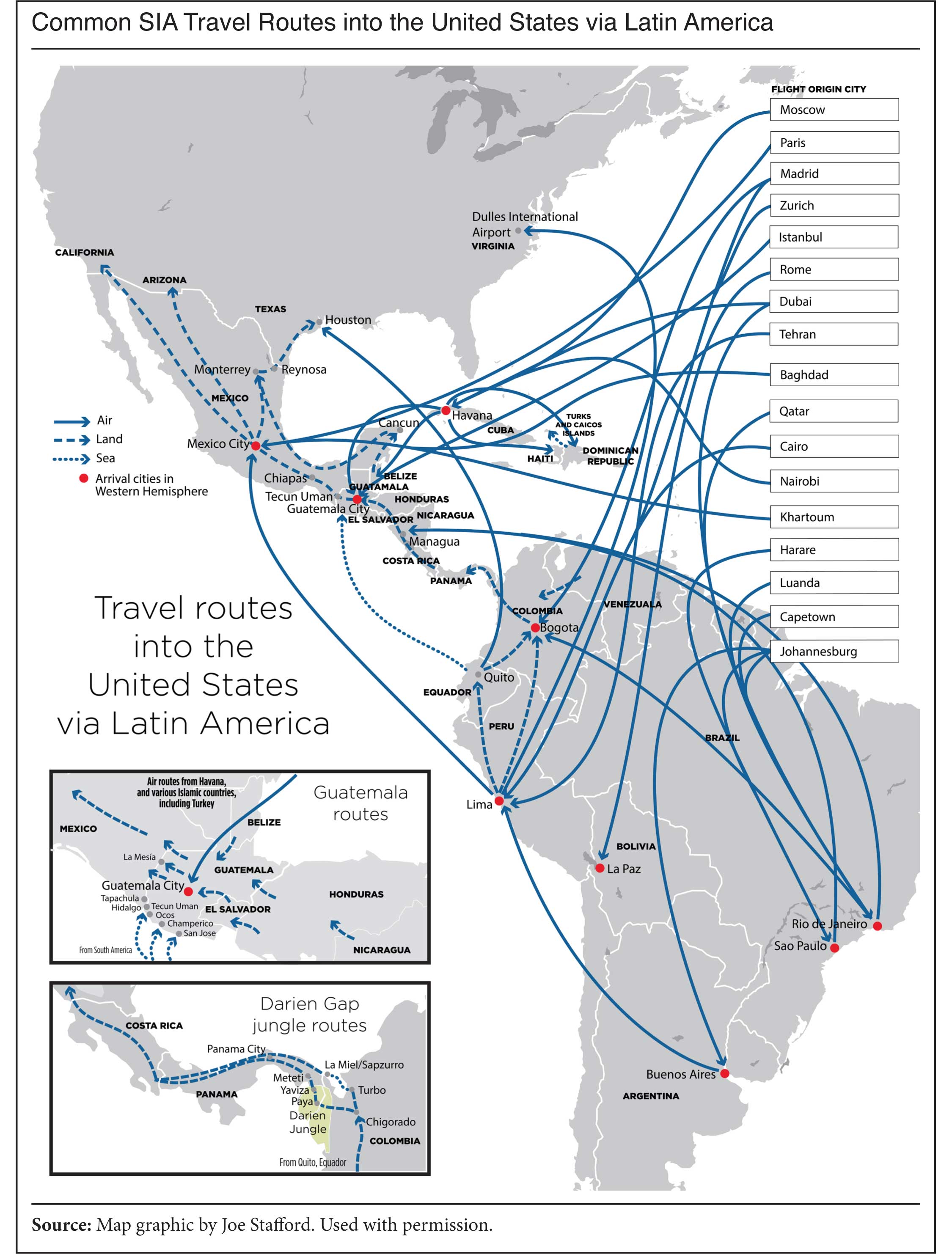

The risk of terrorist-migrant infiltration through the U.S. southern border probably remains more moderate than for Europe, but likely increased after the 2015 Paris attacks, for three reasons:

- Terrorist organizations such as ISIS would be fully aware that infiltration over European borders repeatedly succeeded as an innovative tactic that is replicable at the U.S. border and desired.

- Smuggling networks that transport migrants from the same origin countries to Latin America and the U.S. border are well established and accessible even under law enforcement pressure and at higher expense, providing travel capability for either deployed operatives or sympathizers.

- Terrorist vetting and detection processes at the U.S. border and along the Latin America approach routes, though more effective than were Europe's, are flawed and remain vulnerable to easy defeat.

To better understand why the threat of terrorist infiltration over the U.S. border might have increased, some risk-mitigating differences between terrorist migration to Europe's external borders and to the U.S. southern border warrant acknowledgement and discussion. Three key differences involve: the volume of migration flows from Muslim-majority countries, the size and complexity of geographies that must be policed, and relative capabilities on both sides of the Atlantic to screen entrants for suspected terrorism.

A Deterring Distance and Expense

Europe's baseline asylum, security vetting, and refugee systems collapsed under the onslaught of refugees and migrants who often arrived without identity documents, enabling dozens of successful clandestine jihadist entries. But even prior to the crisis, Europe had not oriented its collective attention toward illegal immigration as counterterrorism because border infiltration had not emerged as a terror-travel tactic. In short, it had not happened yet. In contrast, federal legislation after 9/11 did require the United States homeland security enterprise to preemptively recognize border infiltration as a vulnerability and to orient some programs to attenuate it.94

The degree of effectiveness may well have hinged on that difference in security preparedness and in migration flow volumes.

Whereas most of the 2.5 million migrants who entered Europe during the crisis hailed from countries of the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia, only an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 migrants from the same regions annually reach the U.S. southern border.95 For example, the Department of Homeland Security stated that in 2018 a fractional 3,000 of the 467,000 illegal immigrants apprehended at the southern border were categorized in government parlance as "special interest aliens" (SIAs) based on citizenship in countries where terrorist groups operate.96

High SIA migration from Muslim-majority countries to an unprepared Europe resulted in terror attacks while low migration to a more prepared United States has resulted in no terror attacks on U.S. soil to date.

One reason for lower volumes of SIA migrants at the U.S. border is that distances to reach it are far greater and more cost prohibitive than for them to reach European entry points at Greece, Italy, Spain, and Hungary. Transportation and smuggling fees to staging points in Turkey, Libya, and Morocco, by boat over three main Mediterranean Sea routes, and then internally inside Europe were relatively affordable to the masses.97

A journey to Europe might average less than $5,000 while one to the U.S. border can cost tens of thousands of dollars more. For instance, a typical journey from distant West Africa to Europe would be priced in the $2,000-$3000 range.98 Costs to cross the Mediterranean from Libya, Morocco, or Turkey to a European border might have added an additional $900 to $4,000 during 2015.99

By contrast, migrants traveling to the U.S. southern border require air travel to reach Latin America and the cost of air travel is the least of it. Using passenger flight requires other expensive smuggler services such as obtaining identity and visa documents to both exit and enter airport customs inspections. Guides, lodging, and other forms of transportation also are necessary to traverse South America, Central America, and Mexico. Whereas, for instance, an Afghan or Pakistani migrant might pay several thousand dollars to reach Turkey and then perhaps $1,000 boat passage fare to Greece, the same migrants might have to pay from $20,000 to as much as $60,000 to reach the U.S. border.100

Perhaps more than any other factor, high costs and identity and visa documents should prevent migration from special interest migrant countries from ever spiking to European proportions that overwhelm systems enough to increase risk. However, mass migration waves from other countries such as Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala in 2018 and 2019 can and did degrade terrorist-vetting capabilities.

American Preparedness vs. European Union Preparedness

If several thousand special interest aliens do reach the U.S. border every year, a question worth answering is whether they are better managed for counterterrorism security than were those that reached Europe. The answer is a qualified affirmative that American management of lower migration volumes reduced the risk of terror attack, though persisting vulnerabilities will be described.

Like Europe did prior to 2014, U.S. and DHS strategy recognized the need for a "transnational" approach to counterterrorism with immigration control, meaning border security agencies extended their activities beyond physical frontiers to other continents.101 But prior to the first attacks in 2015, the 28 European signatory nations of the Schengen Area (22 of the European Union) had not advanced as far in this as had the Americans, who began pushing border security outward shortly after 9/11. European countries did not have interoperable intelligence databases or common terrorism watch lists, systems to check asylum applicants against common or allied terrorist databases, or mechanisms to share derogatory information among agencies and countries in a timely manner.102

With 27,000 miles of external sea border and 5,500 miles of land border to secure, EU countries also faced far greater logistical challenges than did the United States with its singular northward corridor approaches through Latin America. Only in 2014, as various Arab Spring rebellions propelled 276,000 migrants from Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Eritrea, a 155 percent increase from the prior year, did Schengen counties deploy agencies and programs abroad to collect intelligence about human smuggling networks.103 While EU law enforcement agencies such as Frontex and Europol did conduct counter-smuggling enforcement operations prior to the crisis, these efforts clearly did little to stem the coming tide and were quickly overwhelmed.

By contrast, the post-9/11 United States developed capabilities to share counterterrorism intelligence, to check migrants against terrorist database matches, and to dismantle special interest migrant smuggling operations abroad.104 This counter-smuggling task was assigned to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Homeland Security Investigations branch, which deployed hundreds of agents to dozens of transit countries in the years after 9/11.105

The United States trained and equipped transit countries like Panama and Costa Rica to collect biometrics to identify migrants passing through from all over the world.106

Meanwhile, at the physical border, starting in 2004, U.S. Customs and Border Protection implemented protocols to screen SIAs in detention, including in-person FBI and DHS threat assessment interviews, terrorism database checks, biometrics collection, and checks of intelligence repositories.107 After 9/11, FBI and DHS agents stationed in Mexico conducted threat assessment interviews inside Mexican detention centers.108

Unlike in Europe, efforts such as this produced intelligence that fueled the ICE counter-smuggling investigations, generated new intelligence on travelers, and also identified potentially dangerous migrant-terrorists both en route and at the U.S. border.

American Success in Infiltration Detection and Attack Prevention?

In the European theater, the dearth of government preparedness for terrorist border infiltrations led to high casualties and severe, wide-ranging negative societal impacts. In contrast, no migrant who crossed the U.S. southern border had conducted a terror attack after September 2001 except for one Somali who crossed the Mexico-California border in 2011 and went on to allegedly commit a 2017 vehicle-ramming attack while carrying an ISIS flag in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.109

It would, however, be a logic fallacy to cite the absence of a terror attack or few numbers of terrorist suspect interdictions as evidence of a very low or no threat.

The absence of border-breaching attacks such as those that occurred in Europe can be partly attributed to American efforts that have consistently detected and apprehended intelligence-flagged terrorist suspects at the border or en route to it, perhaps preventing some from committing the outsized societal harms of their European predecessors. Obviously, prevented terror attacks and impacts that never took place cannot be confirmed and tallied with much certitude. But in the American theater, screening at the border and intact intelligence-sharing with transit nation governments almost certainly took identified prospective migrant-terrorists off line before they could act.

For example, between 2012 and 2017, authorities involved in screening and investigative activities reportedly identified more than 100 SIAs on U.S. terrorism watch lists — at least 20 per year — apprehended at the border or en route through Latin America.110 People are entered on watch lists if they become investigative suspects in plots or attacks, are directly or indirectly involved with terrorist organizations, or are dangerous individuals. Presence on the watch lists is a strong indicator of higher risk to public safety. It is worth remembering that a mere 19 al-Qaeda hijackers attacking in New York and Washington, D.C., on 9/11 defeated a variety of immigration systems and set the United States on nearly two decades of wars abroad.

U.S.-bound SIA terror suspects continued to be apprehended from 2017 to 2019, including four suspected ISIS operatives in Nicaragua, an al-Shabaab suspect and several terror suspects in Costa Rica, and six Pakistani al Qaeda suspects in Panama.111 Since 9/11, at least 15 named border-crossing terror suspects became publicly visible due to terrorism-related prosecutions in U.S. courts or leaked intelligence reporting about their apprehensions or deportations, including several Somalis whose terrorism involvements were extensively documented.112 Counter-smuggling investigations in recent years in Latin America identified numerous terror-watch-listed migrants from Somalia, Afghanistan, Yemen, Pakistan, and some from unnamed countries.113

None of these apprehended migrants would have been free to conduct attacks, if they were planning any, since they were apprehended, prosecuted on various charges, imprisoned, or deported. These interdictions by themselves, and probably many more publicly unknown ones, profoundly demonstrate the presence of problematic SIAs, baseline risk, and threat despite the lack of successful attacks since September 2001.

There are other reasons why that steady-state risk and threat persist despite interdiction successes so far.

Holes in the Net

Significant vulnerability to border infiltration persists even though some threat reduction can be attributed to American counter-smuggling abroad, intelligence sharing, and security screening at home. Public reporting indicates ineffectiveness of effort, inconsistent application, discordant inter-agency coordination, and a highly dysfunctional asylum system. Determined terrorist travelers arriving with false or no identity documents and an unverifiable asylum persecution story can easily slip the American net. And not all travelers with terrorism history have been entered into an intelligence database.

In a 2016 memo, as migrant-involved terror attacks were mounting in Europe, then-DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson ordered 10 top agency chiefs to address a perceived lack of coordinated emphasis on SIAs "who are potential national security threats to our homeland."114 Johnson directed his chiefs to assess "shortfalls, limiting factors, and potential areas for improvement" in the country's effort and draft a coordinated plan to systematically reduce the national security threat he saw from this migration. As of 2018, however, the Johnson initiative was no longer active as DHS agencies went their separate ways.115

Indeed, a variety of government accountability reports indicate inconsistent or uncoordinated attention to the problem set and little oversight by the various responsible agencies and Congress to assess the effort and remedy shortfalls. One 2010 Congressional Research Service report noted that, because much of the external border security operations involving intelligence services was classified, "there is no way to account for the ... contribution" of U.S. agencies working on illegal migration abroad.116

ICE's special interest alien smuggling operations in Latin America achieved some disruption success in the years after 9/11, undoubtedly reducing flow numbers at least temporarily and helping to identify some terrorist suspects.117 For instance, ICE-HSI in 2018 and 2019 arrested an Afghan smuggler in New Jersey and a Jordanian smuggler in Mexico; Iranian, Pakistani, Algerian, and at least two Somali smugglers in Brazil; and two Bangladeshi smugglers in Mexico.118 But one 2012 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report noted that more than 80 percent of ICE-HSI efforts abroad had been diverted to drug cases, underlining missed opportunities to reduce the number of migrants and detect threatening ones.119 Reports like this, along with a relatively consistent annual flow rate of 3,000 to 4,000 special interest migrant apprehensions at the southern border annually since September 2001, indicate that the ICE effort is under-resourced and only episodically disrupts flow.

Meanwhile, at the physical border in U.S. detention centers, FBI and DHS agents reportedly have not been conducting threat-assessment interviews of all apprehended SIAs before they bond out to freedom in the country's interior, on backlogged asylum claims, conditions that enabled Europe's terror attacks.120 In 2011, the FBI ceased universal interviews to concentrate on select high-priority SIAs while ICE intelligence officers were largely unable to reach 100-percent interview goals before detainees bonded out without enhanced vetting.121 In Mexico, too, FBI and DHS have long been permitted to interview SIAs in Mexican facilities, starting a few years after 9/11.122 But limited staffing allowed no more than a few interviews at a time, leaving most to continue on to the American border unscreened.123

In any case, the FBI and DHS systems of assessing terrorism connections are far from foolproof.124 A contributing factor is that migrants often show up with no identification or hail from countries that maintain no databases and haven't worked with American intelligence or law enforcement for decades, such as Syria, Somalia, Libya and a number of other origin countries.125 Said one FBI agent of these circumstances: "You interview them, run every database possible, fingerprints, watch lists, check their stories. ... Could we be fooled? Of course."126

A 2012 GAO investigation of the Border Patrol, despite a priority strategic plan requirement that it deter and screen SIAs, found that agency was doing little and did not regard the issue as its problem.127 The report found that hundreds of such migrants were only getting caught at interior Border Patrol highway checkpoints, including several on the U.S. terror watch list.

Perhaps most pertinent, the U.S. asylum system apparently has provided no more of a screening opportunity than did the European asylum system after it had completely broken down, and provides at least as much time as migrant-terrorists enjoyed in Europe. Perpetual backlogs in the intact U.S. asylum process were far longer than were backlogs in Europe when it was nearly defunct. In the United States, the backlog had grown to more than 800,000 by January 2019, with the average wait time being 578 days, or about 19 months.128 The backlog exceeded one million by September 2019.129 The lengthy adjudication period matters to counter-terrorism in the United States, just as it did in Europe, because SIAs tend to file asylum claims and bond out to live and work — or plot.

Furthermore, asylum fraud is rampant and rarely detected, investigated, or prosecuted, according to GAO reporting over the last decade. The reporting shows an absence of fraud detection training or capability, high rates of undetected fraud, and little inclination among agencies to investigate or prosecute.130 A 2015 GAO report on the system's continuing vulnerability to fraud found, in part, that responsible investigative agencies in all field offices will not investigate asylum fraud because U.S. Attorneys reject most referrals and infrequently, if ever, prosecute asylum fraud.131

Numerous U.S. smuggler prosecutions showed that special interest migrant smugglers actively exploited asylum system flaws, often by coaching clients to claim false persecution stories or to omit disqualifying personal history in interviews with American adjudicators and in immigration court.132 In fact, smugglers embroidered asylum fraud into their business models. The asylum system was regarded as so vulnerable to terrorist infiltration that DHS's 2008-2013 threat assessment noted the agency's "highest level of concern" was that "terrorists will attempt to defeat border security measures with the goal of inserting operatives and establishing support networks in the United States" by posing as "refugees or asylum seekers ... from countries of special interest for terrorism."133

Conclusion

The authors of the 2018 White House Counterterrorism Strategy may not have had the benefit of a better scope of terrorist border infiltration in Europe in 2018, but this developing picture of what happened demonstrates they were prescient in noting that something new and significant had happened with potential implications for U.S. border security. Longer distances, higher costs, and American security and counterterrorism intelligence capabilities likely have deterred some migrant-terrorists from risking the journey and, along with apprehensions of terror suspects, may partly explain the absence of attacks to date. However, expense, distance, and the chances of discovery would not likely dissuade determined terrorists well aware that their co-religionists have succeeded in Europe. Terrorist infiltrators never entered into an intelligence database, or ideologues prone to be influenced by extremist online incitement, are likely to defeat the limited American security cordons, too. ISIS, the group most often responsible for sending suicide bombers into Europe posing as migrating refugees, retained vast cash resources well after its military defeat in Iraq and Syria, and therefore the capability to pay higher smuggling fees.134 Well aware of its infiltration feats in Europe, ISIS reportedly had plans to repeat them at the American border in 2016, when its leadership sought to arrange the smuggling of a team of Trinidadian foreign fighters from Syria over the U.S. border.135

The largely undisturbed smuggling networks that would carry determined, resourced foes along with 3,000 to 4,000 SIAs each year therefore must still be regarded as a heightened threat, so long as terrorists are aware of the option and so long as U.S. efforts remain uncoordinated, under-resourced, and neglected.136 The arrival of even small numbers of terror suspects at or en route to the American border reinforces what was learned in Europe: that only a relative few successes will have outsized impacts throughout American society.

End Notes

1 "European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2017", Interpol, 2017, p. 14.

2 Nicholas Rasmussen, "Terrorists and the Southern Border: Myth and Reality", Just Security, January 8, 2019; Josh Feldman, "Jeff Flake Responds to Trump's 'Unknown Middle Easterners' Tweet: 'A Canard and a Fear Tactic'", Mediaite, October 22, 2018; Franco Ordonez, "Trump officials exaggerate terrorist threat on the southern border in tense briefing", The Washington Post, January 4, 2019; Calvin Woodward, "Trump's mythical terrorist tide from Mexico", Associated Press, January 8, 2019.

3 "President Bush Releases National Strategy for Combatting Terrorism", February 14, 2003.

4 "National Strategy for Counterterrorism of the United States of America", The White House, October 2018, p. 8.

5 Ibid., p. 8.

6 "Risk Analysis for 2018", Frontex, February 2018, p. 8.

7 Julia Gelatt, "Schengen and the free movement of people across Europe", Migration Policy Institute, October 1, 2005; "Roles and Responsibilities", Frontex website, undated.

8 "Risk Analysis for 2018", Frontex, February 2018, p. 8.

9 Stacy Meichtry and Joshua Robinson, "Paris Attacks Plot Hatched in Plain Sight", The Wall Street Journal, November 24, 2015; "Paris Stadium Attacker Entered Europe Via Greece", The Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2015; David Gauthier-Villars, "Paris Attacks Show Cracks in France's Counterterrorism Effort", The Wall Street Journal, November 23, 2015.

10 "National Strategy for Counterterrorism of the United States of America", The White House, October 2018, p. 15.

11 "European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2017", European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation, 2017, pp. 6, 12, 14; Dion Nissenbaum and Julian E. Barnes, "Brussels attacks fuel push to close off militants' highway", The Wall Street Journal, March 23, 2016; Alan Yuhas, "NATO commander: ISIS spreading like a cancer among refugees, masking the movement of terrorists", The Guardian, March 1, 2016; John Stevens, "How the Paris bomber sneaked into Europe: Terrorist posing as a refugee was arrested and fingerprinted in Greece — then given travel papers and sent on his way to carry out suicide bombing in France", Daily Mail (UK), November 16, 2015; Isabel Hunter, "Master bomb-maker who posed as migrant and attacked Paris last year is now chief suspect in Belgian atrocity as police swoop on home district", Daily Mail, (UK), March 22, 2016.

12 Sam Mullins, Jihadist Infiltration of Migrant Flows to Europe: Perpetrators, Modus Operandi and Policy Implications, London: Palgrave Macmillan, Febraury 26, 2019; Robin Simcox, "The Asylum-Terror Nexus: How Europe Should Respond", Heritage Foundation, June 18, 2018; "Risk Analysis for 2018", Frontex, February 2018, p. 8.

13 All data collected for study and analysis, terrorists and suspects killed and arrested in Europe 2014-2018, is available here.

14 "What is NVIVO?", NVIVO website, undated.

15 To be counted as "confirmed", reporting should have cited law enforcement, intelligence, or government sources as establishing routes and methods of entry. To be counted as "strong probability", reporting should have identified a subject as an asylum seeker or refugee who entered the EU during the peak years of the migrant crisis and was of a nationality then crossing the borders in high volumes. Other circumstantial information, such as arrests in asylum centers, often added weight to judgements to include suspects in the "strong probability" category and final tally. By necessity, the numbers may fluctuate over time since some of the cases were in legal adjudication as of December 2018 and eventual exoneration would be grounds to remove them from these tallies, while others that should have been included were overlooked.

16 "Anis Amri", the CounterExtremism Project, undated.

17 Kim Sengupta, "Ansbach explosion: Angela Merkel under pressure over refugee policy after fourth attack in one week", Independent (UK), July 25, 2016.

18 Anthony Faiola, "Islamic State claims German suicide bomber was former militant fighter", The Washington Post, July 27, 2016.

19 "German train attack: IS releases vido of 'Afghan knifeman'", BBC, July 19, 2016.

20 Jennifer Newton and Allan Hall, "ISIS axe attacker Mohammed Riyad may have lied about being from Afghanistan", Daily Mail (UK), July 20, 2016; "Investigators doubt the origin of the perpetrator", Spiegel Online, July 19, 2016.

21 "Four suspects remanded in custody over Turku knife attack, one man freed", Yle Uutiset, August 23, 2017.

22 Sewell Chan and Mikko Takkunen, "Finland Attack Suspect, a Moroccan Youth, Was Flagged for Extremist Views", The New York Times, August 21, 2017.

23 Tuomas Forsell, "Finish court names knife attack suspect", Reuters, August 21, 2017; "Moroccan asylum seeker 'targeted women' in Finland terror stabbing", AFP, August 20, 2017.

24 Gaetano Mazzuca, "Syrian detained as a smuggler accused of terrorism", La Stampa, November 05 2016.

25 "Syrian refugee jailed over Germany bomb plot", Deutsche Welle, December 20, 2018; "German police arrest Syrian suspect, avert 'major terrorist attack", Reuters, October 31, 2017.

26 Axel Spilcker, "He already made the bomb! 16-year-old Syrian got bombing instructions in chat", Online Focus, April 12, 2016; "16-year-old Syrian convicted of terrorist plans", Zeit Online, April 10, 2017.

27 Steven Erlanger, "Profile Emerges of Suspect in Attack on Train to Paris", The New York Times, August 22, 2015; "France train shooting suspect profile: Ayoub El-Khazzani", BBC, August 25, 2015.

28 Jean-Charles Brisard and Kevin Jackson, "The Islamic State's External Operations and the French-Belgian Nexus", Combatting Terrorism Center Sentinel, Vol. 9, No. 11, December 2016.

29 Clark Bentson, "Asylum seeker instructed to drive vehicle into a crowd, Italians say", ABC News, April 26, 2018.

30 Thomas Pany, "War crimes: Federal Prosecution goes against al-Nusra members in Germany", Telepolis, June 12, 2017; "Al Nusra member committed suicide in prison", ANF News, August 31, 2017.

31 Alice Philipson, "Tunisian terrorist returns to Europe posing as asylum-seeker", The Telegraph, November 9, 2015; Kellan Howell, "Ben Nasr Mehdi, Islamic terrorist, caught trying to enter Europe on migrant boat", Washington Times, November 10, 2015,; Hannah Roberts, "Al Qaeda boss who served seven years for terror offenses smuggled himself into Europe by posing as a refugee", Daily Mail, November 8, 2015.

32 Gerhard Piper, "Jihadists in the stream of refugees", Heise Online, September 10, 2017.

33 "Did he plan attacks in Europe? Confidant of IS war minister Chalimov caught", Online Focus, October 15, 2016.

34 "Gemany jails Syrian refugee over Canadian UN observer's abduction", Canadian Broadcast Service, September 21, 2017.

35 "Syrian man tried in Germany over abduction of Canadian UN observer", Associated Press, October 20, 2016; Gerhard Piper, "Jihadists in the stream of refugees", Heise Online, September 10, 2017.

36 Anthony Faiola and Souad Mekhennet, "Tracing the path of four terrorists sent to Europe by the Islamic State", The Washington Post, April 22, 2016.

37 Jean-Charles Brisard and Kevin Jackson, "The Islamic State's External Operations and the French-Belgian Nexus", Combatting Terrorism Center Sentinel, Vol. 9, No. 11, December 2016.

38 Ibid.; Rukmini Callimachi, "How ISIS Built the Machinery of Terror Under Europe's Gaze", The New York Times, March 29, 2016.

39 Paul Cruickshank, "Raid on ISIS suspect in the French Riviera", CNN, August 28, 2014.

40 Rukmini Callimachi, "How ISIS Built the Machinery of Terror Under Europe's Gaze", The New York Times, March 29, 2016.

41 Giovanni Legorano, "Italian Police Arrest Algerian Suspected of Involvement With Paris, Brussels Terrorists; Djamal Eddine Ouali suspected of supplying false documents, aliases", The Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2016; Valentina Pop and Giovanni Legorano, "Brussels Attacks: European Authorities Tighten Net on Suspected Terror Cell", The Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2016.

42 Ruth Bender, "Germany Accuses Asylum Seeker of Aiding Paris Attacks Leader", The Wall Street Journal, July 7, 2016; Guy Van Vierden, "Fllowing the Facebook trail of Abdelhamid Abaaoud's scouts", Emmejihad, March 19, 2018.

43 Rukmini Callimachi, Allissa J Rubin, Laure Fourquet, "A view of ISIS's Evolution in New Details of Paris Attacks", The New York Times, March 19, 2016.

44 "Islamic State suspects face terrorism charges in Germany", Associated Press, March 8, 2017.

45 Melissa Eddy, "Germany Charges 4 Syrians in Plot to Attack Dusseldorf", The New York Times, June 2, 2016.

46 Anthony Faiola, "Germany arrests 3 suspected Syrian terrorists, foils possible Islamic State plot", The Washington Post, June 2, 2016.

47 Allan Hall, "Police arrest suspect who planned terrorist atrocity after seeking sanctuary in Germany", Express (UK), August 11, 2016; Jorg Diehl, "Terrorist Suspect Khaled H.: Investigators find torture video in raid", Der Spiegel, December 8, 2016.

48 Ben Knight, "Germany deports Tunisian terror suspect to 'likely torture'", Deutsche Welle, August 3, 2017.

49 Kamailoudini Tagba, "Germany: Tunisian Arrested for Alleged Membership with IS Group", The North Africa Post, December 16, 2016; Gerhard Piper, "Jihadists in the stream of refugees", Heise Online, September 10, 2017.

50 "German train attack: ISIS releases video of 'Afghan knifeman'", BBC, July 19, 2016.

51 "ISIS releases video of alleged Bavaria train attacker calling on Muslims to kill 'infidels'", RT, July 19, 2016.

52 Jennifer Newton and Allan Hall, "ISIS axe attacker Mohammed Riyad may have lied about being from Afghanistan", Daily Mail (UK), July 20, 2016.

53 "Asylum Procedures", European Commission Migration and Home Affairs, undated.

54 "Anual Report on the Situation of Asylum in the European Union 2015", European Asylum Support Office, 2016.

55 Ibid., p. 19; "Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in the European Union 2016", European Asylum Support Office, 2017, p. 10.

56 "Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in the European Union 2016", European Asylum Support Office, 2017, p. 24.

57 Tom Batchelor, "Terror in Brussels: Gunman shot in Paris attacks raid was illegal migrant with ISIS flag", Express (UK), March 16, 2016.

58 "IS Christmas bomb plot:Munir Mohammed and Rowaida el Hassan jailed", Sky News, February 23, 2018; "Pair jailed for UK homemade bomb attack plan", BBC, February 22, 2018.

59 Mark Misérus, Kaya Bouma and Maaike Vos, "In the footsteps of inconspicuous attacker of CS Amsterdam, Jawad S: 'There is zero perspective for Afghans'", de Volkskrant, September 7, 2018.

60 Valentina Pop and Ruth Bender, "Germany Ill-Prepared for Terror Fight, Critics Say", The Wall Street Journal, December 22, 2016; "Germany bomb threat: Jaber al-Bakr caught by three Syrians", BBC World News, October 10, 2016.

61 Redazione Roma, "Terrorism, suspected jihadist stopped near Termini", Rome Chronicle, October 6, 2017; Daniele Raineri, "Bachir the blowhard", Il Foglio, October 9, 2017.

62 Andrea Thomas, and Nour Mohammad Alakraa, "Syrian Accused of Islamic State Links Arrested in German Refugee Camp", The Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2015.

63 Robin Simcox, "The Asylum-Terror Nexus: How Europe Should Respond", The Heritage Foundation, June 18, 2018.

64 "Asylum Procedures", European Commission, Migration and Home Affairs website, accessed September 23, 2019.

65 John Mueller and Mark Stewart, "Terrorism and Bathtubs: Comparing and Assessing the Risks", presentation at the Annual Convention of the American Political Science Association, Boston Mass., August 30, 2018; Alex Nowrasteh, "Terrorists by Immigration Status and Nationality: A Risk Analysis, 1975-2017", Cato Institute, May 7, 2019; Alex Nowrasteh, "Center for Immigration Studies Shows a Very Small Threat from Terrorists Crossing the Mexican Border", Cato Institute, November 28, 2018.

66 "Effects of terrorism: A trauma and victimological perspective", United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, July 2018; "The cost of terrorism in Europe", Rand Corporation, undated.

67 "The cost of terrorism in Europe", Rand Corporation, undated; Wouter van Ballegooij and Piotr Bakowski. "The fight against terrorism: Cost of Non-Europe Report", European Parliamentary Research Service, May 2018, p. 41.