This is the third of five reports on the issues surrounding the placement of thousands of unaccompanied children from Central America in communities across the United States.

See also:

Brentwood, N.Y., Consumed by MS-13 Crime Wave

Implementation of a Law to Protect Trafficking Victims Has Become a Public Safety Issue

Joseph J. Kolb, M.A., is a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Key points:

- According to federal Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) data obtained by the Associated Press, more than 80 percent of UAC sponsors are in the United States illegally. Federal agencies have few mechanisms, and apparently little inclination, to hold sponsors accountable for failure to comply with deportation proceedings.

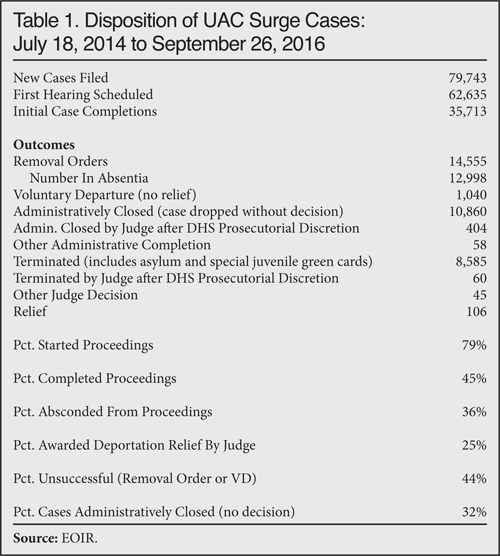

- Over the last two years, approximately 13,000 Unaccompanied Alien Children (UACs) skipped out on their immigration court hearings. This represents 36 percent of the cases completed. So far, 25 percent of the UACs whose cases have finished were granted permission to stay, 44 percent were ordered deported, and 32 percent had their case dropped without a decision.

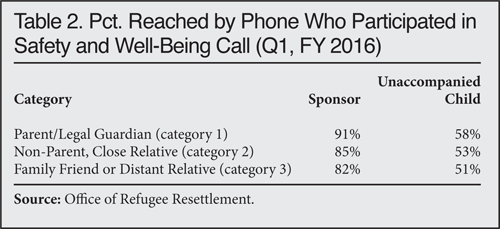

- A significant share of sponsors and youths have not been reached in follow-up phone calls from ORR. Nine percent of parental sponsors, 15-18 percent of non-parental sponsors, and less than half of the youths have been reached in these calls. The compliance rate of UACs housed with illegal sponsors is not tracked.

- UACs reportedly have been transferred from ORR-approved sponsors to unvetted third parties without consequence.

- Federal agencies say they have no mechanism to hold non-compliant sponsors accountable, especially those already in the United States illegally.

- The prevailing policy facilitates illegal immigration and enables criminal activity in the United States by allowing criminal gangs and trafficking organizations to take advantage of these lax policies.

- The prevailing policy empowers tens of thousands of illegal immigrants to evade the law and creates the impression for others that they also can come illegally with impunity.

Introduction

A large segment of the Central American unaccompanied children who have arrived in the United States since 2014 have been placed with illegal immigrant sponsors by the ORR, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. These sponsors are not monitored to ensure that they comply with the provisions of the children's placement, either by this agency, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR, which runs the immigration courts) or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE, which handles immigration enforcement in the interior). Widespread non-compliance contributes to further swelling of the ranks of those in the country illegally, with the full knowledge and tolerance of the federal government. It has had a deleterious effect on public safety in the places where some of these youths have become recruiting fodder for the violent MS-13 gang.

The goal of ORR is to release minors who arrive illegally and "unaccompanied," usually from the Central American countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, in the least restrictive environment possible, as quickly as possible, ideally with a parent or family member, regardless of their immigration status. This influx, numbering 126,985 unaccompanied minors apprehended by the U.S. Border Patrol from FY 2014 through FY2016, and the choice of the Obama administration to release them into the country to await drawn-out deportation proceedings, has placed a monumental burden on an already strained immigration detention and court system.1

While the public statements by top Obama administration officials sounded tough, in fact the federal government's system of tracking these youths is impotent. More than 80 percent of the youths are placed with sponsors known to already be in the United States illegally, and there is no mechanism in place to hold those individuals accountable when they violate the terms of a child's placement and federal immigration obligations, they, too, are violating.2

From Unaccompanied to Unaccounted For

The chain of custody for UACs begins with the U.S. Border Patrol, whose agents encounter the youths and then refer them to ORR, whose resettlement contractors must place the children with sponsors. According to HHS data obtained by the Associated Press, at least 80 percent of the youths are placed with a sponsor who is already in the United States illegally.3 EOIR, which resides in the Department of Justice, will then manage the immigration court case. If there is a violation in the process or the child is ordered removed from the country, then the responsibility shifts to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to conduct the removal.

Initially a child is placed in temporary housing facilities until a sponsor can be located and vetted. While this vetting appears to be comprehensive on paper, it is light at best, and negligently expeditious at worst. A U.S. Senate investigation released in 2015 revealed a litany of shocking defects in ORR policies for placing newly arrived minors.4 These policies have drastically compromised the agency's ability to protect the minors or to detect human trafficking, debt labor, gang involvement, and other abusive situations.

According to ORR data, in FY 2014, 53,515 unaccompanied alien children were placed with a sponsor; in FY 2015, it was 27,840; and in FY 2016, it was 52,147.5 These placements total 133,502 UACs placed with sponsors. If, as the AP found, 80 percent were placed with a sponsor who is an illegal alien, then that would mean that approximately 106,802 UACs have been placed in illegal alien households.

This in and of itself should raise concern among lawmakers about the impact this policy has on the prevailing illegal immigrant population who by living and working here are openly defying federal law. But when these sponsors, who are given a direct and endorsed responsibility by the federal government and then the federal government fails to enforce its expectations, that reinforces the message that enforcement of immigration laws is not taken seriously.

The following information was provided to the author by EOIR to give a perspective as to the court compliance of UACs and their sponsors.

From 2014 through 2016, the Border Patrol apprehended 126,985 Central American UACs. Over roughly the same period, from July 18, 2014, through September 26, 2016, EOIR received 79,743 new charging, or Notice to Appear, documents for respondents whom DHS had identified as UACs (see Table 1). Of those, 62,635 have had at least one initial, or master calendar, hearing as of the end of the time period. For the same time period, there have been 35,713 initial case completions (ICC) for unaccompanied children. Of these 35,713 ICCs, 14,555 were removal orders (44 percent). Of the cases in which the youth was ordered removed, 12,998, an alarming 89 percent, were issued in absentia, meaning that the youth failed to appear. That represents 36 percent of the total number of completed cases — a high rate of absconding from the due process provided to them.

Many of the cases were simply dropped by the government; 10,860 cases were administratively closed by DHS and 404 were dropped by the judge after DHS indicated that the case would not be a priority, for a total of 32 percent of the cases simply being allowed to drop off the docket without a decision.

Only 8,700, or 25 percent out of the nearly 36,000 completed cases, resulted in the youth being given a legal status, such as asylum or a special green card for juveniles.

Asked to explain the 79,743 apprehended and given NTAs compared to the 62,653 who had hearings, Kathryn Mattingly, an EOIR spokeswoman, told the author that EOIR began docketing the initial master calendar hearing for respondents, whom DHS has identified as UACs, no earlier than 30 days and no more than 90 days from the immigration court's receipt of the NTA from DHS. As such, the first master calendar hearing is still pending for some UC respondents whose charging documents have been filed with the immigration court.

She also explained the 26,922 difference between those who had hearings and cases completed as, "There are no definitive conclusions to be drawn from calculating the difference between the number of master calendar hearings held for UC cases and the number of UC initial case completions. UC cases, as with all immigration cases, frequently involve a number of actions that occur between an initial master calendar hearing and an initial case completion."

The compelling numbers to consider here are the 12,998 UACs who never showed for a court hearing and were ordered removed in absentia. The number of these UACs that were housed with illegal immigrants has not been disclosed or tracked.

According to information given to the author by EOIR, in the top five areas where UACs are placed by ORR (Los Angeles, Houston, Long Island, N.Y., Arlington, Va., and Baltimore, Md.) 95 percent of court-issued removal orders were in absentia. These areas already have large Central American populations. Some of these same areas also have been plagued with spikes in MS-13 gang activity in recent years. This places a strain on local social, health, and educational resources. The fact that these children are either attracted to or are coerced into joining local street gang cliques has been well documented by the author in a previous report dealing with the strife occurring in Brentwood, Long Island.6 And yet, no sponsor has ever been held accountable.

Despite these figures, Mark Weber, spokesman for ORR, says the protocols are being diligently followed. "The sponsor is responsible for the child's care and well-being," Weber told the author.

According to Weber, potential sponsors for unaccompanied children are required to undergo basic background checks and complete a sponsor assessment process designed to try to identify risk factors and other potential safety concerns. As a part of the release process, all potential sponsors must undergo a criminal public records check.

ORR also conducts background checks on adult household members and individuals identified in a potential sponsor's care plan. Additionally, a fingerprint-based background check is required if the screeners believe there is a documented risk to the safety of the minor, the minor is especially vulnerable, if the case is referred for a home study, if any other special concern is identified, or if the sponsor is not the child's parent or legal guardian. The fingerprints are cross-checked with the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) national criminal history and state repository records, which includes DHS arrest records. ORR also requires a home study before releasing any child to a non-relative sponsor who is seeking to sponsor multiple children or has previously sponsored or sought to sponsor a child and is seeking to sponsor additional children. ORR also requires a home study for children who are 12 years and under before releasing to a non-relative sponsor.

On paper ORR's screening of sponsors may appear comprehensive, but given discrepancies revealed by law enforcement in criminal investigations, the process is cursory at best.

According to ORR data, in FY 2015 only 1,895 home visits were conducted out of 33,726 DHS referrals.7 One can reasonably assume the other placements were based largely on self-reported information, which was likely dubious. Anecdotal information has revealed that many children have been placed in environments unprepared for them financially, environmentally, and socially. In some cases, UACs have been reported as placed with members of the MS-13 gang. One Border Patrol agent told the author that he is aware of numerous cases where a child was placed with a sponsor who merely provided a post office box and not a physical address as required.

Following placement, the process again appears to be diligent on paper, but in reality is symbolic. Weber says that ORR calls each household 30 days after the child is released to check on the child's well-being and safety. The purpose of the follow-up call is to determine whether the child is still residing with the sponsor, is enrolled in or attending school, is aware of upcoming court dates, and is safe.

According to ORR, of those reached by phone during the first quarter of FY 2016, only 56 percent of unaccompanied children and 88 percent of sponsors participated in a call.8 (See Table 2.) The lowest rates of participation in the follow up phone calls were the sponsors in Category 3, those placed with a family friend or distant relative. For those who aren't reached, there is no further action by ORR and for those who decline to participate there is no penalty or enforcement attached to non-compliance.

Observers in communities where UACs have been placed said they have personally seen occasions where children have been switched out of the initial sponsor's care to a third party with no consequences.

These children eventually disappear in a bureaucratic black hole that increases in depth and diameter, making locating them and holding sponsors accountable for myriad immigration violations virtually impossible in many cases.

Lack of Sponsor Accountability

The author asked Weber if ORR had a formal follow-up mechanism to determine whether a youth remained with the officially recognized sponsor.

He answered, "Correct, that is another reason why we scrutinize potential sponsors and the household and provide children information on how to stay in contact with ORR."

Under current policies, these removals are not an ICE priority, meaning that the youth likely will disappear into society.

"As part of the civil immigration enforcement priorities announced by Secretary Johnson in November 2014, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement focuses its enforcement resources on individuals who pose a threat to national security, public safety and border security. This includes convicted criminals and those apprehended at the border while attempting to unlawfully enter the United States," ICE spokesperson Jennifer Elzea told the author.

"As the secretary has stated repeatedly, our borders are not open to illegal migration. If someone was apprehended at the border, has been ordered removed by an immigration court, has no pending appeal, and does not qualify for asylum or other relief from removal under our laws, he or she must be sent home. We must and we will enforce the law in accordance with our enforcement priorities," Elzea said.

Therein lies the crux of the matter. Once a sponsor and UAC learn the system of non-compliance, they know their infraction merely is an administrative blip on the ICE priority radar, unless they commit a felony or other very serious crime. Even with blood on their hands, the suspect still may not face deportation, if, for example, sanctuary policies prevent ICE from learning of them.

Implications

After a slight abatement in UACs crossing the border in 2015 compared to the surge of 2014, USBP is seeing another surge. Most recently, at the conclusion of FY 2016 the Border Patrol apprehended 46,893 UACs. The reasons continue to be debated, as economic opportunity, fleeing gang violence, and the perception that they will be allowed to stay all play a role. However, what can't be debated is the lack of oversight and the public safety consequences it breeds. The U.S. Department of Justice has determined that MS-13 is the largest gang on Long Island, which has been plagued by a rash of violent crimes.9 The Texas Department of Public Safety has elevated MS-13 from a Tier 2 to Tier 1 gang, directly blaming the UAC crisis on an increase in crime there.10 According to the report, "Although a large number of MS-13 members have been captured along the border, it is likely many more have successfully crossed into Texas and remain hidden from law enforcement. Gang members from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador could be destined for locations in Texas with large Central American communities, including the Houston and Dallas areas. Law enforcement agencies in Houston already report the highest number of identified MS-13 members in the state."

Many believe that the driving force of the new surge is the perception and even reality of impunity once a UAC is in the system. Sponsors and UACs have learned to work and wait out the system, giving them ample opportunity to mingle in society with little risk of being deported, placing overwhelming burdens on municipal social, health, and educational resources with no concurrent assistance from the federal government to accommodate these population increases.

Conclusion

The federal agencies tasked with processing more than 200,000 unaccompanied children from Central America — DHS, ORR, and EOIR — since 2012 have been overwhelmed by the task. The lenient policies adopted by the Obama administration facilitated this phenomenon and helped fuel the cancerous spread of MS-13 and its heinous breed of violence that has taken some American communities completely by surprise. The federal government continues to saturate these communities, without communicating with local law enforcement or schools, saying they need to protect the privacy of the children and the sponsors.

Remedies that should be considered by lawmakers to mitigate the issues associated with lack of enforcement of the sponsor responsibilities include the following:

- An immediate moratorium on using illegal immigrants as sponsors unless they agree to be placed in deportation proceedings and comply with immigration laws.

- Prompt referral to ICE and appropriate consequences when a UAC or sponsor fails to comply with the provisions of the placement.

- Sponsors who violate their responsibilities should be subject to consequences. Under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, minors must be protected from peonage through coercion, and placement with a gang member or associate should be prohibited, as should placing the UAC with a third party without notifying ORR.

- Modify the TVPRA and other policies to close loopholes that have been exploited by advocates for illegal aliens and Obama administration officials to accelerate the release of minors.

- Monthly notification of local officials, to include law enforcement, health and education officials, and the public by ORR of UAC placements in the community, including identification of the sponsors.

End Notes

1 "Southwest Border Migration", U.S. Customs and Border Protection website, updated January 18, 2017.

2 Amy Taxin, "AP Exclusive: Immigrant kids sent to adults lacking status", Associated Press, April 19, 2016.

3 Ibid.

4 See table on "Home Studies and Post-Release Programs", in "Facts and Data", U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Refugee Resettlement website, last reviewed December 21, 2016.

5 "Unaccompanied Children Released to Sponsors By State", U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Refugee Resettlement website, last reviewed January 30, 2017.

6 Joseph J. Kolb, "Brentwood, N.Y., Consumed by MS-13 Crime Wave", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, NOvember 2016.

7 See table on "Home Studies and Post-Release Programs", in "Facts and Data", U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Refugee Resettlement website, last reviewed December 21, 2016.

8 "Safety and Well-Being Calls First Quarter FY 2016", U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Refugee Resettlement, May 2016.

9 "MS-13 gang leader sentenced to 365 months imprisonment for 2009 murder and attempted murder", U.S. Attorney's Office, eastern District of New York, June 28, 1013.

10 "Texas Gang Threat Assessment", Texas Department of Public, August 2015.