Introduction

During a five-day visit to the United States in February 2008, Mexican President Felipe Calderón lectured Washington on immigration reforms that should be accomplished. No doubt he will reprise this performance when he meets with President George W. Bush and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper in New Orleans for the annual North American Leaders Summit on April 20-21, 2008. At a speech before the California State Legislature in Sacramento, the visiting head-of-state vowed that he was working to create jobs in Mexico and tighten border security. He conceded that illegal immigration costs Mexico "a great deal," describing the immigrants leaving the country as "our bravest, our youngest, and our strongest people." He insisted that Mexico was doing the United States a favor by sending its people abroad. "Americans benefit from immigration. The immigrants complement this economy; they do not displace workers; they have a strong work ethic; and they contribute in taxes more money than they receive in social benefits."1 While wrong on the tax issue, he failed to address the immigrants’ low educational attainment. This constitutes not only a major barrier to assimilation should they seek to become American citizens, but also means that they have the wrong skills, at the wrong place, at the wrong time. Ours is not the economy of the nineteenth century, when we needed strong backs to slash through forests, plough fields, lay rails, and excavate mines. The United States of the twenty-first century, which already abounds in low-skilled workers, requires men and women who can fill niches in a high-tech economy that must become more competitive in the global marketplace.

Most newcomers from south of the Rio Grande have had access to an extremely low level of education, assuming they have even received instruction in basic subjects. Poverty constitutes an important factor in their condition, as well as the failure of lower-class families to emphasize education in contrast to, say, similarly situated Asian families. These elements aside, Mexico’s public schools are an abomination — to the point that the overwhelming majority of middle-class parents make whatever sacrifices are necessary to enroll their youngsters in private schools where the tuition may equal $11,000 to $12,000 annually.

The primary explanation for Mexico’s poor schools lies in the colonization of the public-education system by the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE, according to its initials in Spanish), a hugely corrupt 1.4 million-member organization headed by political powerhouse Elba Esther Gordillo Morales. Rather than lecture American lawmakers on what bills to pass, Calderón would do well to devote himself to eliminating this Herculean barrier to the advancement of his own people within their own country.

This Backgrounder will (1) examine Mexico’s educational levels, (2) discuss the enormous influence of the SNTE’s leader Elba Esther Gordillo Morales, (3) focus on corruption in the educational sector, and (4) indicate reforms that the administration of President Calderón should consider.

I. Educational Levels

Mexico’s educational system teems with ugly facets, none more alarming than the high dropout rate. Roughly 10 percent of those who finish elementary school never complete middle school, either because their families cannot afford to send them, they drop out to earn money, or there is simply no room for them.2

"There is a bottleneck in the system," says Eduardo Vélez Bustillo, education specialist on Latin America at the World Bank. "Quality is bad at every level, but middle school is a crisis point because that’s where the demand is highest," he adds.3 Although Mexico has made significant strides in recent years by increasing overall enrollment and boosting investment in education, the country still trails other developed nations in most proficiency standards.

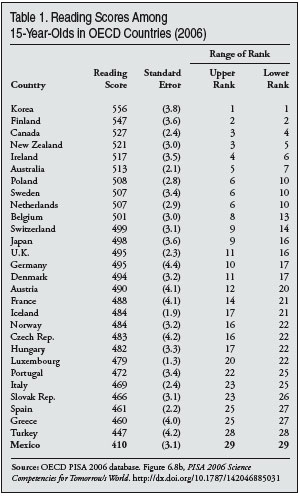

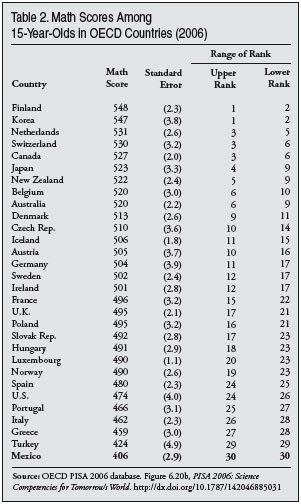

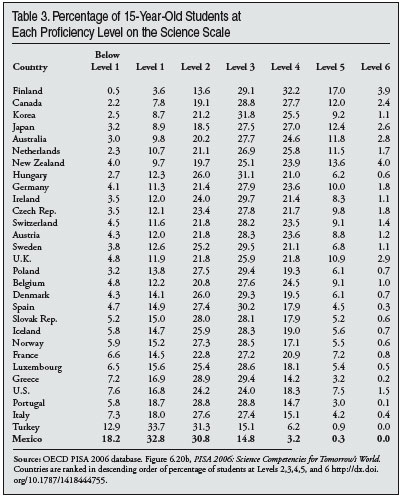

In 2006 the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) conducted its triennial Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) among ninth-graders.4 As indicated in Tables 1, 2, and 3, Mexican students placed at the bottom in reading and mathematics among youngsters in the 30 OECD member nations. Of the 27 non-OECD countries assessed, Mexico fell below Chile, China (Taipei), Croatia, Estonia, Hong Kong, Israel, Romania, Russia, and Slovenia in three areas. Other measures, including student hours in class, show Mexico as an underachiever.

The elementary school day provides for only four hours of instruction in an outmoded curriculum that has been handed down from generation to generation and is zealously guarded by the change-averse SNTE. In lieu of creative approaches to stimulate students, teachers stress rote learning and harsh discipline as evinced in their mantra: "Be Quiet, Pay Attention, and Work in your own seat!"5 In indigenous areas, instructors sometimes use students to perform menial chores for them. This same ethos of submissiveness to strong, hierarchical control characterizes the teachers’ relationship to their union.6

Although the Mexican government could do more, its expenditure on education shot up 47 percent from 1995 to 2004. Spending per student rose only 30 percent because of expanding enrollments.7 Educational spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) exceeds the OECD average at 5.4 percent, including 26.8 percent of the federal discretionary budget. When private sector outlays are added, total educational spending came to 7.1 percent of GDP in 2006.8 In 2004 Mexico’s disbursements on education as a percentage of national income (6.4 percent) surpassed that of all other OECD nations with the exception of Denmark, Iceland, Korea, New Zealand, and the United States.9 Some 95 percent of expenditures are for teachers’ salaries. Inadequate resources have prompted the Ministry of Public Education (SEP) to seek funds from the private sector to rehabilitate 3,200 deteriorating schools.10

U.S. taxpayers pick up the bill for poorly educated Mexicans who cross into this country unlawfully. All told, federal, state, and local governments in 2004 spent $12 billion annually for primary and secondary education for children residing unlawfully in the five states with the most illegal immigrants.11

President Calderón’s secretary of public education, Josefina Vázquez Mota, has championed major reforms of her country’s schools. Gordillo loyalist and SNTE Secretary-General Rafael Ochoa Guzmán said that the PISA findings "affirm the diagnostics that sustain the SNTE’s proposal for a new educational model for Mexico in the XXI century and indicate how much we must do to achieve the objective of quality education that we have identified and upon which we are embarked."12 Such soaring rhetoric aside, Gordillo and Ochoa have mobilized their political allies to block changes, insisting that the real solution lies in pouring even more money into a failed system.

II. SNTE and its Leader

The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) dominated Mexican politics for 71 years after its founding in 1929. The president bestrode the apex of an iron triangle: one side consisted of the PRI, which was synonymous with the government, and the other side depicted an economy dominated by the state. This authoritarian regime imposed top-down control through three sectors to which party members belonged according to their occupations: peasants, blue-collar union members, and public employees. Among public employees, the SNTE constituted the strongest force. After all, teachers, who are in classrooms from the U.S. border to the Guatemalan frontier, were often considered leaders in rural communities because of their superior education. In compliance with directives from their honcho, they worked assiduously on behalf of PRI candidates.

After Carlos Salinas de Gortari became president in late 1988, hundreds of thousands of angry, placard-waving teachers stormed into Mexico City’s zócalo central plaza, protesting the losses incurred during the previous years when educational expenditures fell 40 percent and teacher salaries plummeted by 50 percent.13 When SNTE Secretary-General Carlos Jonguitud Barrios, a former governor of the state of San Luis Potosí, could not restore order, the chief executive removed him. In his place, Salinas installed Gordillo, who has become known as "la Maestra" — a respectful term for a teacher. She showed no remorse at conniving to oust her mentor and patron. When asked about the transition, she said: "I am at peace with my past." The president gave Gordillo a fat and juicy bunch of carrots with which to mollify disgruntled union activists — namely, tens of millions of dollars (498 million pesos) to finance a Teachers’ Housing Fund (VIMA), which could buy land and construct apartments and homes for members of her profession. Ricardo Raphael de la Madrid, a political analyst who has written a book, Los socios de Elba Esther (The Partners of Elba Esther), claims that the president later directed deposits totaling 81.5 billion pesos into housing-related trusts for the union. He observes that an additional 10.82 billion pesos flowed to the labor colossus in the form of subsidies for its department stores, pharmacies, congresses, seminars, and union events. Years later, Gordillo allegedly ordered her ex-husband, Francisco Areola Urbina, to destroy or modify any documents that might flash red lights about the organization’s finances.

Born in 1945 in fly-specked Comitán, in the state of Chiapas, Gordillo remembers growing up amid poverty. In a Wall Street Journal interview, she said that her grandfather, who became rich running a distillery, fathered 41 of his 46 children out of wedlock. A machista tyrant, he disowned Gordillo’s mother Estela, when — against his wishes — she married a policeman. After her husband’s death, Estela lived from hand-to-mouth as a public school teacher.14

Gordillo herself was widowed at age 18 after donating a kidney to her dying spouse. She followed in her mother’s footsteps, teaching in the countryside and, later, in one of Mexico City’s poorest areas. As a teenager, she joined the SNTE and, as a stalwart in the Revolutionary Vanguard, a dissident current within the union, began excoriating Jonguitud for his corrupt and ineffective leadership.

Rather than lash out at this fiery, young upstart, Jonguitud invited her into his leadership circle and, reportedly, into his bed.15 This ensured Gordillo’s meteoric ascent through the ranks of her profession. Critics claim that with her intimate friend Jonguitud’s blessing, she won a disputed contest to head the SNTE in México State, the most populous of the country’s 31 states. Firebrands in the National Coordination of Educational Workers (CNTE), a radical anti-Gordillo rival that embraces one-fifth of the nation’s teachers, even allege that she orchestrated the assassination of one of her opponents, Misael Núñez Acosta — a charge that Gordillo vehemently denies.16

Soon after becoming the SNTE boss, Gordillo thwarted efforts by Education Secretary Manuel Bartlett Díaz to decentralize public education, modernize the curriculum, fortify the role of parents, and, in the process, weaken the union. Rather than rejecting this initiative outright, la Maestracame up with a Union Movement for the Modernization of the Educational System, which proved to be nothing more than a blueprint for preserving the status quo.17

3">La Maestra rose in the PRI apace with her upward movement in the SNTE. Her political posts include three terms in the Chamber of Deputies (1979-82, 1985-88, 2003-06); one period in the Senate (1997-2003); a key operative in the her party’s fraud-ridden "victory" in the 1986 gubernatorial contest in Chihuahua when she served as Secretary of Organization of the National Executive Council (1986–1987); general secretary of the Council of National Popular Organizations (1997–2002); and secretary-general of the PRI (2002-2005). On July 13, 2006, two weeks after the federal elections, the PRI announced her expulsion from its ranks for having supported Calderón, the candidate of the center-right National Action Party (PAN) and for attacking and slandering the PRI’s leaders and candidates.

Gordillo stepped down as the SNTE’s secretary general in 1994 to become the "life-time president" ("presidenta vitalicia"). She also relishes the sobriquet as the union’s "moral leader." Regardless of her title, she has preserved her hammerlock on the union through handpicked lieutenants: Humberto Dávila Esquivel (1995-98), Tomás Vázquez Virgil (1998-2001), and Rafael Ochoa Guzmán (2001-present). Her wealth and power prompted scholar M. Delal Baer to refer to her as "Jimmy Hoffa in a dress" — a comparison with the deceased boss of the Teamsters International Union.18 Social scientist Jorge Zepeda Patterson has gone even further, calling her the "Darth Vader of Mexico."19

Opponents within the PRI forced her out of the party’s number-two position in 2005. At that point, she devoted herself to organizing a teacher-based New Alliance Party (PANAL), which fielded a presidential candidate and nominees for the Chamber of Deputies the following year. Although mentioning

her intention to retire, Gordillo continues to flex her political and economic muscles thanks to several factors:

-

She heads the largest union in Latin America, with 1.4 million members.

-

SNTE controls the Democratic Federation of Public Employees’ Unions (FEDESSP).

-

She manages the expenditure of nearly $60 million per year derived from the $5 (53 pesos) that the teachers pay each month in dues.

-

She has accumulated hundreds of millions of dollars in resources that enable her to exert an iron hand over the SNTE bureaucracy and most of the largest of its 55 locals.

-

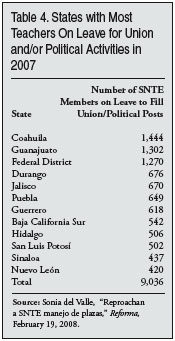

As presented in Table 4, at least 9,000 SNTE members collected paychecks in 2007, but did not teach classes. Another 14,000 enjoyed "leaves of absence" while retaining their jobs. Of the 18,574 union members who did not work, 81.2 percent were employees of Mexico’s 31 states or the Federal District; the others held posts in decentralized organizations like the National Polytechnic Institute.20

-

Thousands of SNTE members hold positions in Mexico’s Ministry of Public Education (SEP), including Gordillo’s son-in-law, Fernando González Sánchez, who is undersecretary of primary education.

-

One of her stalwarts, Miguel Ángel Yuñes Linares, runs the State Workers’ Social Security System (ISSSTE), which has discretion in providing health services and subsidized housing to bureaucrats.

-

Another loyalist, Roberto Campa Cifrián, is technical secretary of the National Public Security Council, which provides funds to states and municipalities to combat organized crime.

-

She operates the SNTE Foundation for the Culture of the Mexican Teacher (FCM) through which she provides jobs to cronies and grants to the many intellectuals she has befriended.

-

She engineered the election of the last president of the Political Council of the Federal Election Institute (IFE), which compiled the voter registry, trained poll workers, supervised the balloting, and disseminated the preliminary results of the 2006 presidential election.

-

Her National Alliance Party boasts nine seats in the Chamber of Deputies (including one held by her daughter, Mónica Arriola Gordillo), and one senator, Irma Martínez Marínquez, who now identifies herself as an independent.21 Humberto Moreira Valdés, a social science teacher and SNTE leader, holds the governorship of Coahuila state as a member of the PRI; other governors with whom Gordillo has close links are Eduardo Bours Castelo (Sonora), José Natividad González Parás (Nuevo León), Eugenio Hernández Flores (Tamaulipas), and Eduardo Peña Nieto (Mexico State).

-

Calderón owes his eye-lash thin victory over a populist to PANAL voters. While Gordillo urged her faithful to support PANAL legislative candidates, she encouraged them to cast ballots for Calderón, candidate of the center-right National Action Party (PAN), for chief executive. Calderón won by 233,831 votes out of 41.5 million cast. The difference in votes for PANAL’s legislative aspirants (1,876,443) and its presidential standard-bearer (397,550) totaled 1,478,893 votes.

III. Corruption in SNTE

Corruption thrives in the SNTE, which has control over the hiring and firing of teachers. Among these venal, or at least highly questionable, practices are:

-

SNTE does not sign an annual collective bargaining contract with the federal and state educational authorities. Rather, the union’s executive committee and the leaders of locals submit to the president and governors an extensive list of demands—they involve salaries, fringe benefits, health-care, housing, hiring and promotion practices, holidays, access to teachers’ colleges or normal schools, the number of union leaders on the public payroll, recreational and vacation facilities, donations to union training programs, and myriad other items—that are either accepted or set aside for renegotiation. At the termination of this Byzantine process, a memorandum or set of "minutes" is agreed upon, but only a select group of individuals understand the terms of the so-called "Dark List of Demands" ("Pliego Negro").

-

Over the years, the government has paid for modern union headquarters in the upscale Portal del Sol de Santa Fe section of Mexico City, a Teachers’ Library, also located in the capital, and various hotels and vacation centers for SNTE members.

-

A "closed shop" allows the SNTE to exercise favoritism in hiring teachers. This discretion helps explain the 46 percent failure rate among 268,849 primary-school teachers who voluntarily took a national professional examination in 2007 (1,195,543 initially registered for the test). Moreover, 46 out of 100 teachers do not possess the credentials appropriate for their educational assignments.22

-

Teachers in Local 36—a Gordillo stronghold in the Valley of Mexico—complained that some 38 million pesos had been deducted from their salaries over the years for housing that never materialized. Members of the local in Chipancingo, Guerrero, also claimed fraudulent deductions.

-

The scattering of "small deposits" of $300,000 to $400,000 in as many as 70 bank accounts to make it difficult to ascertain the union’s wealth.23

-

She convenes secret meetings of SNTE’s National Political Council at which important decisions are made in violation of union statutes.24

-

Her acquisition of at least four apartments and six houses in the exclusive Lomas de Chapultepec and Polanco neighborhoods of Mexico City, valued at $6.8 million (68 million pesos); property in the deluxe Coronado Cays development in San Diego, Calif., where her yacht is moored; properties in France, England, and Argentina; private jets; and "a personal fortune … [of more] than $300 million in cash," according to a longtime key operative.25

-

Participation in the buying and selling of tenured teachers’ jobs for $5,000 or more.26

-

Although job selling is illegal, union leaders often take a cut of the amount paid for a teaching position.27

-

Requiring the federal and state governments to withhold union dues from locals that oppose Gordillo’s leadership.

-

Rather than hiring on merit, it is customary for deceased teachers’ children to have the right of first refusal for their jobs. If no one wants the post, the spouse often sells it.28

-

Placing in a bank account $186 million (1,863 million pesos) that the Education Ministry provided to the SNTE to purchase computers for teachers under the Program for Educational Technology and Information.29

-

Failing to account for hundreds of millions of dollars in the Teachers’ Housing Fund whose unaudited accounts were reconfigured and absorbed by other government agencies.30

-

Protecting teachers who do not show up for class.31

-

Obscuring expenditures of $432 million (4,321 million pesos) between 2000 and 2006 related to the New Technology program designed to purchase 400,000 computers for teachers to use in their classrooms or homes.32

-

Working to ensure lucrative opportunities for allies through her personal friend, Yánez Herrera, who heads the National Lottery. These include a $1.6 million to $4 million (16 millones, 149 mil 925 pesos to 40 millones 346 mil 999 pesos) to contract for construction of the Médica Londres, a hospital owned by Jorge Kawagi Macri, president of Gordillo’s National Alliance Party; the payment in 2007 of $42,000 (423,000 pesos) to Manuel Gómora Luna, coordinator of the Foundation Alliance for Education of PANAL; and a monthly payment to Gómora of $4,400 (44,000 pesos) as SNTE’s representative to the State Workers’ Social Security Institute (ISSSTE).33

-

Sending in out-of-state teachers as shock troops or "buccaneers" to oppose the election of slates opposed to Gordillo as occurred in Local 37 in Baja California.34

-

Promoting teachers to administrators based on their loyalty to the union.

-

Manipulating elections for SNTE leaders at the local and national levels to ensure la Maestra’s hegemony. For example, in March 2004, she received 98 percent of the votes (2,785 out of a total of 2,850) cast by delegates from the 58 locals to win the new post of "executive president" of the union at its V Extraordinary Congress.35

-

Transferring teachers who defy SNTE mandates to poor schools in rural areas or slums.

-

Threatening mass mobilizations against the regimes of governors who do not kowtow to her demands for more resources and political favors.36

IV. Reforms

Education Secretary Vázquez Mota has called for root-and-branch changes in her country’s educational system. She supports regular and systematic evaluation of students and teachers, using merit to determine teachers’ salaries, enrolling more poor children, opening teaching jobs to competition, revising teaching methods, improving teacher-training institutions, introducing appropriate technology, ensuring the safety of students, involving parents in the education of their youngsters, and inviting the participation of the private-sector and the mass media in educational matters. She laid out her ambitious plans in Programa Sectorial de Educación: 2007-2012.37 For her part, Gordillo has pointedly questioned the competence of Vázquez Mota and urged "a dramatic reduction in the enormous cost of the SEP [education ministry] bureaucracy, which by any measure is inefficient and unproductive."38

Conclusion39

While giving lip-service to the same objectives,40 President Calderón has been loathe to cross swords with la Maestra because of the intense political problems that he faces with a Congress dominated by opposition parties. The chief executive also confronts continuous attacks from self-anointed "legitimate president" Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has gone on a rampage against proposals to invite private capital into the nation’s petroleum sector that has only 10 years of proven reserves remaining.

In February 2008, Congress approved a robust increase in teachers’ pay, but failed to require improved performance as a quid pro quo for higher salaries. Meanwhile, Gordillo had the temerity to request the Ministry of Public Education to pay the income tax for teachers — an amount exceeding $475.4

million.41

Amid newspaper attacks on union corruption and growing dissent among locals, Gordillo announced in early March 2008 that she would step down from her SNTE post because of the imperative to have an "orderly generational change in leadership."

She may have made this statement to assuage concerns within Calderón administration that it has become too close to la Maestra — a misgiving voiced by César Nava, now the president’s chief of staff, when he was his private secretary in a meeting with fellow PAN members.42 Her announcement notwithstanding, the SNTE bigwig neglected to state when she

would step down, the means of selecting her successor, and whether she would endorse a dauphin.

One month later, she did an about-face, affirming that she would maintain her hold on the union’s reins for another four years. "I must die some day, but not when others wish it," she said.

The moral leader announced that her intention to "slim down" the organization’s bureaucracy by slashing the size of its National Executive Committee to 19 members. Although Gordillo touted this action as part of placing a "new face of modernity" on the SNTE, in fact she was tightening her grip on the union’s machinery.43

When la Maestra does step down, her daughter Maricurz Montelongo Gordillo, an ex-federal deputy who now represents the Nayarit state government in the capital, her husband SEP Undersecretary Fernando González, and Héctor "the Cashier" Hernández, longtime SNTE money man, have the inside track to succeed her.

Gordillo faces revolts from chiefs of several key locals. The leftist CNTE continually attacks her. At the same time, she has incurred the wrath of important elements of the principal political parties. If he can survive the knock-down-drag out battle over the petroleum issue, Calderón should muster any political capital that he has left to break the back of the SNTE and restore education to the Mexican people to whom its belongs. In so doing, he can improve chances for his citizens to find worthwhile employment in their own land.

End Notes

1Quoted in Victoria Waters, "Calderón pide ayuda en inmigración y comercio," February 14, 2008, Diario las Americas.

2 Chris Kraul, "Mexico’s Schools Can’t Keep Up," Los Angeles Times, September 21, 2004.

3 Quoted in Kraul, "Mexico’s Schools Can’t Keep Up."

5 María Cecilia Fierro and Patricia Carbajal, Mirar la práctica docente desde los valores (Mexico: Gedisa, 2003).

6 Ricardo Raphael, Los socios de Elba Esther (Mexico City: Planeta, 2007), p. 85.

7 David Hopkins et al., An Analysis of the Mexican School System in Light of PISA 2006 (London: London Centre for Leadership in Learning, Institute of Education, University of London, November 2007), p. 9.

8 "The ‘Teacher’ Holds Back the Pupils," The Economist, July 19, 2007.

9 Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, Education at a Glance 2007, p. 206, www.oecd.org/dataoecd/4/55/39313286.pdf

10 Nurit Martínez, "Sep pide a IP adopter escuelas deterioradas," El Universal, April 1, 2008.

11 http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0604/01/ldt.0.html

12 Quoted in "Urgen cambios, reconoce SNTE," El Mañana, December 7, 2007.

13 Rafael, Los socios de Elba Esther, p. 86.

14 Jose de Cordoba, "Gordillo, Top Union Boss and, She Says, ‘No Angel,’ Ascends in the Congress," Wall Street Journal, June 30, 2003.

15 "That I was or was not his lover … I neither deny or confirm. It’s a question that insults my person, because even if it were to be true, nobody can say that that made me Elba Esther;" quoted in de Cordoba, "Gordillo, Top Union Boss and, She Says, ‘No Angel,’ Ascends in the Congress."

16 "Acusan a Elba Esther Gordillo de asesinato," Noticieros Televisa, February 27, 2002.

17 Raphael, Los Socios de Elba Esther, pp. 89-98.

18 Quoted in de Cordoba, "Gordillo, Top Union Boss and, She Says, ‘No Angel,’ Ascends in the Congress."

19 Quoted in "Carta urgente a Elba Esther," El Universal, August 27, 2007.

20 Claudia Guerrero, "Cobran sin dar clases," Reforma, January 17, 2008; and "The ‘Teacher’ Holds Back the Pupils," The Economist, July 19, 2007.

21 Rafael Ochoa Guzmán won a seat in mid-2007, but asked for a leave-of-absence in 2007 to resume his duties as secretary general of the SNTE; his replacement is a Gordillo loyalist.

22 Nurit Martínez, "Maestros reprobados y de ‘panazo,’" El Universal, March 31, 2008.

23 "Las arcas de Elba Esther," La Tarde (Reynosa), December 4, 2007.

24 An example is the July 6-7, 2007, session held in Baja California; see, Wenceslao Vargas Márquez, Milenio, July 9, 2007.

25 Noé Rivera Domínguez quoted in "Las arcas de Elba Esther," La Tarde, March 12, 2007.

26 Reported in a study conducted by Jacques Hallack and Muriel Poisson, Corrupt Schools, Corrupt Universities. What Can be Done? (International Institute for Educational Planning, UNESCO, 2007) and reported in Jessica Meza, "Exhibe la Unesco corrupción en SNTE," Reforma, June 9, 2007.

27 Mary Jordan, "A Union’s Grip Stifles Learning," Washington Post, July 14, 2004, p. A16.

28 "A Union’s Grip Stifles Learning," Washington Post, July 14, 2004, p. A1.

29 "Se embolsa SNTE apoyo a maestros," El Mañana de Matamoros, February 25, 2008.

30 "A la maestra, lo que quiere," Proceso, December 17, 2006 and Rafael, Los Socios de Elba Esther, p.243.

31 Jordan, "A Union’s Grip Stifles Learning," Washington Post, July 14, 2004, p. A16.

32 Raphael, Los Socios de Elba Esther, pp. 249-250.

33 "‘Ganan’ elbistas Lotería," Reforma, March 2, 2008.

34 Rosa María M. Fierros and Julieta Martínez, "Ahora maestros en BC también paran labores," El Universal, June 13, 2006.

35 "El SNTE, de los más corrupto del sindicalismo mexicano," Zeta, November 23-29, 2007, www.zetatijuana.com/html/EdcionesAnteriores/Edicion1756/Portada.html

36 Karina Áviles, "Gordillo chatajea a gobernadores luego de crear movimientos deestabilizadores," La Jornada, November 26, 2006.

37 Published by the Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2007.

38 The comments about the SEP appeared in a SNTE document; see, Sergio Jiménez y Nurit Martínez, "Sólo en documento, Gordillo critica rezagos en educación," El Universal, June 23, 2007.

39 Material from Noé Rivera Domínguez, a former Gordillo insider, contributes greatly to this section; see, Jesusa Cervantes, "Sale Gordillo Fortalecida," Proceso, December 17, 2006.

40 Nurit Martínez, "FCH anuncia sistema de evaluación de maestros y estudiantes en tres meses," El Universal, August 24, 2007.

41 Sonia del Valle, "Exigen maestros les subsidien ISR," Reforma, March 24, 2008.

42 Perla Martínez, "Pide Nava reviser alianza con SNTE," Reforma, November 25, 2007.

43 Laura Poy Solano, "Mantiene Gordillo el control del SNTE," La Jornada, April 4, 2008.

George W. Grayson, who is the Class of 1938 Professor of Government at the College of William & Mary, is a member of the Center for Immigration Studies Board of Directors. He is also a senior associate at the Center for Strategic & International Studies and an associate scholar at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. William & Mary student Gabriela Regina Arias helped edit and proof-read this essay.