Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

David North is a senior fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies. He has been studying various migration streams, both of immigrants and nonimmigrants, off and on since 1969. He is grateful to Dean DerSimonian, a CIS intern, and to Rodney North for their assistance with the research.

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) grants de facto life-long legal status to aliens in the United States (whatever their prior status) because something bad happened in their home country. But recent data shows that people with TPS are the only sub-population among the foreign-born that is shrinking in size. While this is good news — because the program is bad public policy — it does not mean that people leaving the TPS population are actually leaving the country. This paper explores the number of people in TPS and the possible reasons for the decline. In addition, I will propose an alternative to TPS.

There rarely has been a termination of TPS status for a major source of TPS aliens; once granted it has usually been rolled over every 18 months. In a few instances, usually involving very small groups of aliens (such as those from Kosovo and Montserrat), the status has been terminated, but there have been no such decisions since May 2009.

TPS recipients are in what has become, in effect, a permanent legal, non-immigrant status, allowing them to travel overseas and back, and to work legally in the United States. The status does not grant them a path to a green card and they must re-apply every 18 months as their nominal temporary status for aliens from their country is renewed yet again. For reasons that I will get to later, the total number of TPS beneficiaries is shrinking.

In contrast, as my colleagues Stephen Camarota, and Karen Zeigler, have shown,1 the foreign-born population generally keeps growing and is projected to reach 51 million in 2023, a historic peak. Subsets of that population are increasing as well, such as H-1B workers and F-1 students. And though estimates of the number of illegal aliens bob up and down from time to time, the flow of legal immigrants remains steady at the thunderous rate of one million a year

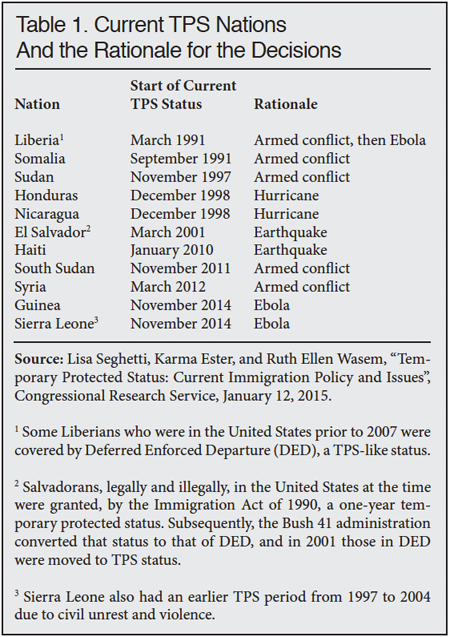

But the government’s estimates of the various current TPS populations are down substantially. I use the plural advisedly, because this is not a single, unified population, it is now a collection of 11 of them, usually created by executive order for one nation at a time. Most recently there was a three-nation decision for the Ebola nations: Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone.2 (This report was written before the government decided to add Nepal to the list of TPS nations.)

The rationale for the TPS determinations have been, in addition to Ebola: armed conflict (e.g., Sudan and South Sudan); an earthquake (Haiti); or terrible storms (Honduras and Nicaragua), which the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security in consultation with the Secretary of State thought were serious enough to grant TPS status to all residents of those nations in this country at the time. Their authority to do so derives from the Immigration Act of 1990.

In contrast, President Obama has no statutory authorization for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which creates a TPS-like class of aliens from all over the world (but mainly from Mexico).

Table 1, largely based on a Congressional Research Service report3 shows the dates on which aliens from 11 nations now eligible for TPS first became eligible for the program and the rationales for those decisions.

There are 10 small populations of aliens whose one-time TPS status has been allowed to expire; nine out of these 10 nations are in the eastern Hemisphere and none are nations that routinely send us large numbers of migrants. These are: Kuwait, 1991-1992; Lebanon, 1991-1993; Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1992-2001; Rwanda, 1995-1997; Sierra Leone, 1997-2004; Burundi, 1997-2009; Montserrat (a British colony in the Carribean),4 1997-2004; Kosovo, then a break-way province of Serbia, 1998-2000; Guinea-Bissau, 1999-2000; and Angola, 2000-2003. These 10 nations sent us 8,596 immigrants in 2012, while the 11 nations in Table 1 accounted for 67,163 immigrants the same year, according to the 2012 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. That is about an eight-to-one ratio.

There are 20 countries in all that now have, or have had, TPS status; Sierra Leone is on both the list of current nations and is among the terminated nations, as it has had two rounds of TPS.5

In addition to TPS, there are or were two other somewhat similar statuses, Extended Voluntary Departure (EVD) and Deferred Enforced Departure (DED); currently only the latter is in effect, and only for a small number of Liberians.6

The TPS Rules

In order to become eligible for TPS benefits an alien from a designated country has to:

- Have arrived in the United States on or before the date the program opens for his nation;

- Have been here continuously since that date;

- Be admissible to the United States (i.e., not have a serious criminal record);

- File for TPS status, and, if he wants a job, for an employment authorization document;

- Pay the associated fees (currently $465 if one wants to work in the United States); and

- Do so before an announced deadline.

Legal status at the time of filing is not a factor. Both aliens with, say, a current tourist visa and illegal aliens can apply for the program. In most cases, TPS offers more benefits than a nonimmigrant visa because it allows for a de facto permanent work permit.

This being the immigration business, and the government a soft touch, there are numerous exceptions to those rules.

Date of Presence. For the largest of the programs (those covering people from Central America) the cutoff date has not changed, but for some of the smaller populations, the eligibility date has advanced in recent years. Each advancement means that larger numbers of aliens, including illegal ones, are eligible for the program.

Three examples of that pattern: The original cut-off date for Haitian presence for TPS was January 12, 2010, two days after the earthquake; later the date was moved forward to January 12, 2011, which meant that those who had come to the United States legally or illegally in the year following the earthquake were also covered by this one-nation amnesty.7

Also, the cut off date for aliens from Somalia was moved from September 1991 all the way to May 2012, a period of 21 years.8 Despite that action, the most recent USCIS estimate of TPS beneficiaries from that country was only 270. (This is puzzling, given the 100,000-plus estimate of Somalis in the Twin Cities alone, and the continuing strife in that country — why so few TPS sign-ups?)

A third example is the cut-off date for Syrians, which was moved forward from March 2012 to January of this year.9

In addition to the sometimes moving cut-off date, another softening of this requirement is the opportunity for TPS-eligible aliens who have not applied previously to do so during the re-registration periods, providing they meet certain standards.

Still another way to beat the cut-off date has recently emerged, but this applies only to a particularly alert, and by definition, tiny subset of TPS eligibles. As I reported in a blog earlier this year, USCIS is now announcing TPS eligibility on the morning of the effective date.10 This means that a would-be TPS beneficiary who is in Canada or Mexico at the time could rush across the border (legally or illegally) and be present in the United States on the last day of eligibility.

Continuous Presence in the United States. A TPS beneficiary, if he can persuade USCIS that he really needs to travel abroad, can usually get an advance parole document that will allow him to leave this country and return without penalty. Going back to the nation from which the alien fled, however, is no-no.11

Paying the Fees. Typically a TPS beneficiary initially pays an $85 biometrics fee for photographing, fingerprinting, and collection of other required data; if he wants to work legally, there is another $380 fee for the employment authorization document (EAD). On re-registration the $380 fee is required, but not an additional biometrics fee. If a once-registered TPS alien wants to continue in status, but not work, no fee is needed. If an applicant can successfully plead lack of funds, both of these fees can be waived. I could find no data on the extent to which TPS fees are waived, but there is strong evidence that the waiving of USCIS fees in general is costing the government much more money as time passes and as the looser rules of the Obama administration take effect.12

Deadlines. As noted earlier, there are ways in which they have been softened in some cases.

The Shrinking of Most TPS Populations

USCIS for some reason, perhaps institutional laziness, has never published counts of the number of TPS documents it has issued. In its announcements of the renewal of TPS status for years it used the word “estimate” in connection with the population figures that appeared in the Federal Register. More recently, “approximately” serves the same purpose in the follow-on notices.13 The agency estimates have varied from time to time, however, indicating to me that the published approximations were based on actual, if unpublished, data. Further, to my knowledge, neither USCIS nor anyone else has published a tabulation of all these populations over time.

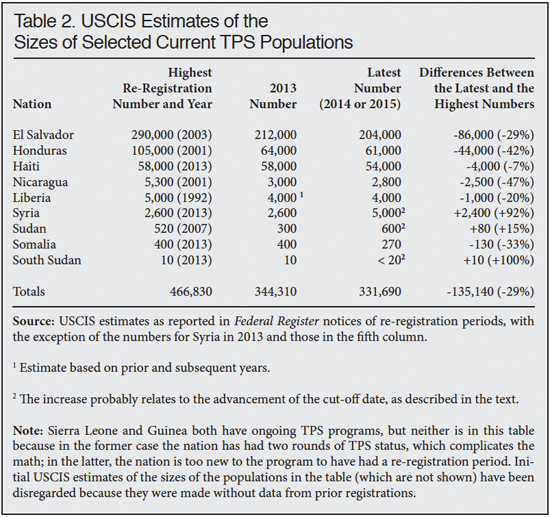

Using the available USCIS estimates, CIS has calculated the apparent total of selected current TPS populations at various times as shown in Table 2.

The question that arises is: What happened to the 135,000 aliens who used to be in TPS status, but are not now? All the major, and some of the minor, programs show substantial declines over the years. Comparing the 2013 data to more recent data shows a continuation of the same process.

This trend is taking place despite the fact that our government is stating, in effect, that things are still terrible in the nations of origin. Further, if one looks at the situation from the point of view of an individual Salvadoran, for instance, one can assume that TPS status in the United States is preferrable, at least in economic terms, to being a full citizen back home. So why the declines?

The TPS population, except in cases where the cut-off date has been moved, is much like the composition of a college class. The maximum number was established on the first day of the freshman year and there have been few if any additions since. However, in subsequent years many leave school and ultimately and slowly death nibbles away at the totals until the last member of the class dies some 80 years after graduation.

Further, births do not add to the actual TPS population because children born to TPS holders are U.S. citizens. I have made no effort to calculate the size of the addition to the U.S. population made by TPS aliens and their U.S.-born children. Given Central American birth rates, one would assume that the TPS-caused population would be much larger than even the highest set of numbers shown in Table 2.

Reasons for Shrinkage. There are several paths that can be taken out of TPS status; some more frequently trod than others:

- Little-used paths: conversion to green card status or to another nonimmigrant class in the United States, migration to a third nation

- Somewhat more common paths: death, return to the mother country

- Most common: reversion to illegal alien status in the United States

These are my best estimates and are, admittedly, supported more by common sense than by statistical bases. Let us look at these six paths in turn.

Green Card Status. My assumption is that most of the Central American TPS aliens were in illegal status before TPS and, of these, most had entered without inspection (EWI). Until 2012, EWIs among the TPS beneficiaries were regarded as ineligible for adjustment of status that otherwise would be available to those with a sponsor (either a U.S. citizen or green card spouse or other relative or an employer). Since then, court decisions have made it possible for the TPS-EWI to adjust status.14

TPS beneficiaries who were inspected on entry probably were a majority of those from Haiti and from the Eastern Hemisphere so they would be eligible for adjustment if they could find a sponsor, but that is a big if. Many, probably most of the TPS beneficiaries do not have either a citizen or green card relative in the United States and it is difficult to secure a labor certification. So obtaining a green card would not be an option for most of the TPS beneficiaries under the current rules.

In addition, however, some TPS aliens have successfully filed for asylum status and now have secured green cards through that route. Also, some of the pre-2000 arrivals, particularly from Nicaragua, have adjusted to green card status under the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA). Similarly small numbers of Haitians, including some presumably in TPS status, have secured permanent resident alien status through specialized legislation regarding people from that nation. In 2012, according to Table 7 in the 2012 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, there were 183 adjustments under NACARA and 83 related to the Haitian legislation. There is no breakdown as to TPS status in that table.

Conversion to Another Nonimmigrant Class. A TPS alien could and can adjust to another nonimmigrant class if eligible, but there would be little reason for doing so as the benefits of TPS status are superior to those in most nonimmigrant categories.

There may be a tiny handful that secured jobs with international organizations, such as the World Bank, and moved into long-term G-visa status (which carries with it freedom from the U.S. income tax). Similarly, if one were to be involved in a long-term academic process, such as seeking a PhD, one might adjust to F-1 status to avoid the $380 cost of renewing one’s EAD every 18 months. Neither of these routes would be useful to more than a miniscule fraction of the TPS population at the very most.

Migration to a Third Nation. A few TPS aliens undoubtedly have moved on to other nations, but that number cannot be very large. Again, the benefits for doing so must be minimal in most cases and there are substantial barriers to overcome. Further, people tend to migrate, if they do so at all, to places where there are at least some of their countrymen, and there are few Central Americans in Canada, the handiest third nation.15

Perhaps some of the Eastern Hemisphere aliens did move to Canada, where the Africa-born population is growing faster than the general population, according to the always helpful Statistics Canada.16

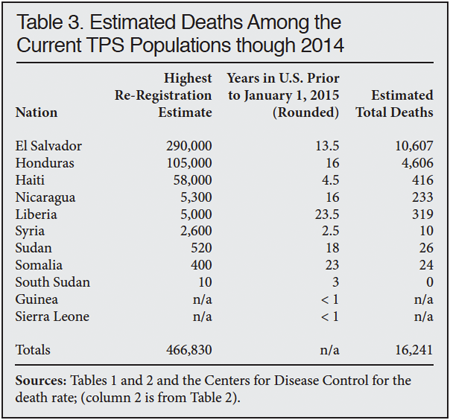

Deaths. Migrants, legal and illegal, tend to be young adults, with relatively few of them in the high-death-rate categories of under one or over 65. On the other hand, many of the TPS aliens arrived here as much as 25 years ago and are now moving into, and in some cases beyond, middle age.

This is somewhat arbitrary, but let’s assume that the death rates for the current TPS populations are comparable to U.S. death rates; further, that the rates for the cohorts established in or before 2002 are for people aged five to 65, and for those established later are for the five- to 55-year-old population. The Centers for Disease Control puts the five-65 rate at 280/100,00 (.28 percent) a year and the 5-55 group at 160/100,0000 (.16 percent) a year.17

In Table 3, I have applied these rates to the current TPS populations, each for the appropriate number of years, and multiplied it by the highest registration estimate as seen in Table 2. (For sake of simplicity I have assumed that the size of each of the 10-year cohorts, such as 35-45 and 45-55, are the same.)

The estimated death totals over the years amount to about 3.5 percent of the highest registration estimates. If anything, the calculation is on the low side for many reasons: The standards of medical care in the home countries — where the TPS aliens spent much of their lives before coming to America — are below those of the United States; further, the TPS aliens have lower average incomes than Americans in the same age groups.

These death rates will rise sharply as these populations move into their 60s and beyond. The TPS populations’ costs to society, despite their current minimal benefit status, will increase as most will be eligible for both Social Security pensions and Medicare benefits.

Return to the Home Country. The pioneer of migration theory, E.G. Ravenstein, back in the late 19th century, set out seven rules of migration, the fourth of which was “Each main current of migration produces a compensating counter-current.”18 There was, to take an extreme example, some return migration of Jews to Germany after World War II.

So some of the TPS recipients must have returned to their home countries, despite the difficult conditions in all of them, which USCIS spells out every 18 months in its re-registration notices.

The question is: How many? There are, to my knowledge, no statistics on the subject. If the U.S. government has problems with data, think what the situation must be like in Honduras, for example. And the return of one’s own citizens is not likely large enough, even in the United States, to create meaningful data sets.

My sense, given the ongoing influx of illegal migrants from El Salvador and Honduras over the Texas border, is that there are many reasons for leaving those countries and, presumably, few reasons for returning to them.

One example of such a return, however, could be a retired TPS recipient with a Social Security pension who wants to return to his or her roots and to a warm climate, carrying a modest monthly check that will go much further in Central America than in the United States. I do not want to get into the intricacies regarding which aliens can receive Social Security benefits in their homelands and which cannot, but TPS status would create no problems for TPS retirees wanting to take their Social Security checks back home.

Social Security data, as one might expect, does not make a distinction between TPS and other beneficiaries, but the totals of returned and pensioned workers are available.19 The numbers of such returnees, of both TPS and non-TPS aliens, are not large in the nations of interest. For example, in 2012 there were these Social Security pension recipients in the four Western Hemisphere TPS nations:

- El Salvador: 1,348

- Nicaragua: 1,099

- Honduras: 710

- Haiti: <500

Three out of four of the numbers above are tiny compared to the populations shown in Table 2; this is not true in for returnees to Nicaragua; but that nation’s migrants play only a minor role in the TPS program.

Return to Illegal Alien Status. My sense is that the five previously described paths do not, collectively, explain the absence of many of the missing 135,000 TPS beneficiaries. I suspect that the reason that a large number of them have not re-signed for the program is that they have noticed that the government’s enforcement of immigration laws in the interior of the nation is so feeble that they need not go through the nuisance, and the expense, of applying yet one more time for TPS.

They already have Social Security numbers and driver’s licenses and, in many cases jobs, and they must sense that these will not be taken away from them if they do not re-up with TPS.

And in the vast majority of cases they are right.

An Alternative to Temporary Protected Status

What should the U.S. government do when there is, in fact, a truly epic disaster in an overseas nation, such as the Haitian earthquake? My suggestion is to simply freeze the migration status of everyone from that nation in the United States, except adjustments of status already under way. There would be no deportations to the country in question and people with short-term visas would have them extended until, say, 30 or 60 days after the freeze period ends.

In this scenario no one illegally in this country would get the bonanza of legal status just because they happened to be in the United States when the problem arose back home. And because there would be no legalizations to undo, it would be easier for our government to decide that the freeze should end than it is now for the government to terminate a TPS status.

If during this freeze period a potential deportee wanted to return, instead of staying in an ICE detention center, that would be permissible.

Conclusion. While TPS decisions are made within the law (as the DACA decision was not), the time has come to rethink this much too generous program.

End Notes

1 See Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler, “Immigrant Population to Hit Highest Percentage Ever in 8 Years: U.S. Census Bureau: 1 in 7 U.S. residents will be foreign-born”, Center for Immigration Studies, April 2015.

2 See David North, “The Ebola Epidemic Is Over in Liberia, but USCIS Has Not Noticed”, Center for Immigration Studies, May 13, 2015.

3 See Lisa Seghetti, Karma Ester, and Ruth Ellen Wasem, “Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues”, Congressional Research Service, January 12, 2015.

4 In this case, the reason for TPS was a volcanic eruption that destroyed much of the island. The UK, incidentally, made TPS-like provisions for the residents, which reminded me that, while all those born on U.S. islands are either citizens or (in the case of American Samoa) nationals who can freely migrate to the U.S. mainland, the UK has no such automatic provision for those living in its overseas territories.

5 See the U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office of Immigration Review website on Temporary Protected Status.

6 For more on these statuses, see Madeline Messick and Claire Bergeron “Temporary Protected Status in the United States: A Grant of Humanitarian Relief that Is Less than Permanent”, Migration Policy Institute, 2014.

7 See Department of Homeland Security, “Extension of the Designation of Haiti for Temporary Protected Status”, Federal Register, June 1, 2015.

8 See U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Extension of the Designation of Somalia for Temporary Protected Status”, Federal Register, June 15, 2015.

9 See U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Extension and Redesignation of the Syrian Arab Republic for Temporary Protected Status”, Federal Register, January 5, 2015.

10 See David North, “How an Alert Undocumented Syrian Could Obtain Life-Long Legal Status – Today”, Center for Immigration Studies, January 5, 2015.

11 See U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website on Temporary Protected Status.

12 See David North, “New Data Show that USCIS Fee Waivers Are Rapidly Increasing”, Center for Immigration Studies, May 18, 2015.

13 The best way to look up a USCIS estimate of the size of a particular TPS population is to search for “TPS, Federal Register”, the name of the country, and the year of interest.

14 See “Court Says TPS Holders Are ‘Lawful Entrants’ and Can Apply to Adjust Status Based on Marriage: Good news for some TPS holders who may be seeking to adjust status to permanent resident and obtain a green card”, Nolo.com, June 11, 2014.

15 Census data, for example, show an El Salvador-born population of 1.1 million in the United States compared to 17,000 in Canada.

16 See the Statistics Canada website on “The African Community in Canada”.

17 See “Worktable 23R: Death rates by 10-year age groups: United States and each state, 2007”, Centers for Disease Control September 20, 2010.

18 See John Corbett, “Ernest George Ravenstein: The Laws of Migration, 1885”, Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science.

19 See Table 5.J11 in “Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin”, Social Security Administration, February 2014.